Creativity & Cultural Production in the Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEM-Affinity Exhibition Publication Online PDF Here

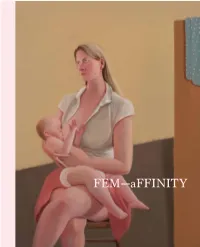

1 — FEM—aFFINITY — 2 FEM—aFFINITY Fulli Andrinopoulos / Jane Trengove Dorothy Berry / Jill Orr Wendy Dawson / Helga Groves Bronwyn Hack / Heather Shimmen Eden Menta / Janelle Low Lisa Reid / Yvette Coppersmith Cathy Staughton / Prudence Flint A NETS Victoria & Arts Project Australia touring exhibition, curated by Catherine Bell Cover Prudence Flint Feed 2019 oil on linen 105 × 90 cm Courtesy of the artist, represented by Australian Galleries, Melbourne BacK Cover Eden Menta & Janelle Low Eden and the Gorge 2019 inkjet print, ed. 1/5 100 × 80 cm Courtesy of the artists; Eden Menta is represented by Arts Project Australia, Melbourne — Co-published by: National Exhibitions Touring Support Victoria c/- The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia Federation Square PO Box 7259 Melbourne Vic 8004 netsvictoria.org.au and Arts Project Australia 24 High Street Northcote Vic 3070 artsproject.org.au — Design: Liz Cox, studiomono.co Copyediting & proofreading: Clare Williamson Printer: Ellikon Edition: 1000 ISBN: 978-0-6486691-0-4 Images © the artists 2019. Text © the authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia 2019. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors. No material, whether written or photographic, may be reproduced without the permission of the artists, authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia. Every effort has been made to ensure that any text and images in this publication have been reproduced with the permission of the artists or the appropriate authorities, wherever it is possible. 3 — Lisa Reid Not titled 2019 -

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES X X I NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are respectfully advised that this book includes the names and images of people who are now deceased. Cover: Detail from Caroline Chisholm's portrait by Angelo Collen Hayter, oil on canvas, 1852, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 459). Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes © Reserve Bank of Australia 2016 E-book ISBN 978-0-6480470-0-1 Compiled by: John Murphy Designed by: Rachel Williams Edited by: Russell Thomson and Katherine Fitzpatrick For enquiries, contact the Reserve Bank of Australia Museum, 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 <museum.rba.gov.au> CONTENTS Introduction VI Portraits from the present series Portraits from pre-decimal of banknotes banknotes Banjo Paterson (1993: $10) 1 Matthew Flinders (1954: 10 shillings) 45 Dame Mary Gilmore (1993: $10) 3 Charles Sturt (1953: £1) 47 Mary Reibey (1994: $20) 5 Hamilton Hume (1953: £1) 49 The Reverend John Flynn (1994: $20) 7 Sir John Franklin (1954: £5) 51 David Unaipon (1995: $50) 9 Arthur Phillip (1954: £10) 53 Edith Cowan (1995: $50) 11 James Cook (1923: £1) 55 Dame Nellie Melba (1996: $100) 13 Sir John Monash (1996: $100) 15 Portraits of monarchs on Australian banknotes Portraits from the centenary Queen Elizabeth II of Federation banknote (2016: $5; 1992: $5; 1966: $1; 1953: £1) 57 Sir Henry Parkes (2001: $5) 17 King George VI Catherine Helen -

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

Lake Macquarie City Destination Management Plan 2018 – 2022 3

CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................... I 1. WORDS FROM OUR MAYOR ............................................................................................ 3 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 4 1. Destination Analysis .......................................................................................................... 5 2. Destination Direction ....................................................................................................... 10 3. DESTINATION ANALYSIS ................................................................................................ 16 1. Key destination footprint ................................................................................................. 16 2. Key assets....................................................................................................................... 17 3. Key infrastructure ............................................................................................................ 19 4. Key strengths and opportunities ..................................................................................... 21 5. Visitor market and key source markets ........................................................................... 23 6. Market positioning ........................................................................................................... 26 7. Opportunities -

ANZAC Memorial Visit

ANZAC Memorial Hyde Park June 2013 On Thursday 27th June the Scouts from 1st Ermington had the opportunity to visit the ANAZ Memorial at Hyde Park in the city. We caught the train from Eastwood station for the journey into Sydney - alighting from the train at Town Hall station. Fortunately the weather was kind and we had a nice walk up to the memo- rial through Hyde park. Although it was early evening and dark the memo- rial looked terrific. The curator for the evening introduced himself to the troop and there was much interest in his background as he was both a Vietnam veteran and a former scout. The evening started with a short video and the scouts were surprised at the footage of the opening because at the time the memorial was the tallest building in the city and the opening was attending by 100,000 people. We were given a tour of the different parts of the memorial (inside and out). Learning about the different parts of the memorial was extremely in- teresting. The Scouts were invited to release a Commemorative star representing an Australian service man or woman killed while serving their country or since deceased - a very humbling experience Another highlight of the evening was the Scouts being able to see a banner signed by Baden Powell. We departed the memorial at 8:20 for our return trip, arriving back into Eastwood at 9:10pm. A big thank you to the Scouts and Leaders that were able to participate in this activity. The ANZAC War Memorial, completed in 1934, is the main commemorative military monument of Sydney, Australia. -

Meeting Every E Pectation

MEETING EVERY E PECTATION Centrally located, the new Holiday Inn Express Wi-Fi and free breakfast. From boardroom Newcastle is the smart choice for the savvy configurations for meetings, team sessions and business events traveller. Offering exactly what you seminars, to group accommodation close to need – simple and smart meetings, a great night’s Newcastle Exhibition & Convention Centre, sleep in a high quality hotel with fast and free we’re meeting your every expectation. ROOM AND Boardroom Theatre U-shape Cabaret ARRANGEMENT Meeting Room 20 36 16 24 (Maximum capacity) ABOUT HOLIDAY INN EXPRESS NEWCASTLE • 170 rooms • Quality bedding with your choice of firm or soft pillows • Complimentary express start breakfast included • Tea and coffee making facilities in room rate • Self-service laundry • Complimentary high speed Wi-Fi • Power showers YOU’RE IN GOOD COMPANY EVENT CATERING Meet smart at Holiday Inn Express Newcastle. Our seasonal catering menu will have you fuelled up and From room hire to full day meetings and catering, ready to go in no time. From morning and afternoon tea we’ve got the perfect space for your event. Excite your packages to tasty lunch platters, we’ve got you covered. guests with modern facilities and complimentary high speed Wi-Fi. Our full day and half day delegate packages offer more where it matters most. THE PERFECT PACKAGES FULL DAY HALF DAY ROOM HIRE ALL OUR DELEGATE DELEGATE ONLY PACKAGES PACKAGE PACKAGE INCLUDE $65 pp $55 pp $75 hourly - weekend Flipchart, whiteboard, (Min 10 people) (Min 10 people) surchage may apply 55” or 65” TV, HDMI, notepads, pens, water and mints WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW AIRPORT Newcastle Airport, 25km PUBLIC TRANSPORT A few minutes walk to Newcastle Interchange, Light Rail and bus stops on King Street, Hunter Street & Parry Street. -

Goulburn River National Park and Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve

1 GOULBURN RIVER NATIONAL PARK AND MUNGHORN GAP NATURE RESERVE PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service February 2003 2 This plan of management was adopted the Minister for the Environment on 6th February 2003. Acknowledgments: This plan was prepared by staff of the Mudgee Area of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The assistance of the steering committee for the preparation of the plan of management, particularly Ms Bev Smiles, is gratefully acknowledged. In addition the contributions of the Upper Hunter District Advisory Committee, the Blue Mountains Region Advisory Committee, and those people who made submissions on the draft plan of management are also gratefully acknowledged. Cover photograph of the Goulburn River by Michael Sharp. Crown Copyright 2003: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. 3 ISBN 0 7313 6947 5 4 FOREWORD Goulburn River National Park, conserving approximately 70 161 hectares of dissected sandstone country, and the neighbouring Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve with its 5 935 hectares of sandstone pagoda formation country, both protect landscapes, biology and cultural sites of great value to New South Wales. The national park and nature reserve are located in a transition zone of plants from the south-east, north-west and western parts of the State. The Great Dividing Range is at its lowest elevation in this region and this has resulted in the extension of many plants species characteristic of further west in NSW into the area. In addition a variety of plant species endemic to the Sydney Sandstone reach their northern and western limits in the park and reserve. -

The Paragon, Katoomba

The Paragon, Katoomba McLaughlin Lecture, Wentworth Falls, 1 March 2014 Ian Jack Fig.1 The Upper Mountains are well supplied with icons both of the natural environment and of the European built environment. The built environment from the later nineteenth century onwards relates overwhelmingly to the tourist industry: the railway which brought city-dwellers up here for holidays, the hotels and guest-houses, the cafés and restaurants and the homes of those who serviced the visitors. I want to talk about one particular café, its local setting and its wider ethnic context, its aesthetics and its archaeology. The Paragon in Katoomba was presciently named by Zacharias Simos in 1916. There are quite a lot of Greek cafés in New South Wales, forming an important heritage genre. But I can think of no other surviving Greek café in the state which has comparable stylishness, integrity and wealth of aesthetic and industrial heritage. The Paragon dates from quite near the beginning of a new phenomenon in Australian country towns, the Greek café. Fig.2 This is the Potiris family café in Queanbeyan 1914. Although the Greek diaspora, especially to America and Australia, had begun early in the nineteenth century, it had gained momentum only from the 1870s: over the following century over 3 million Greeks, both men and women, emigrated. The primary reason for many leaving their homeland in the late nineteenth century was economic, exacerbated by a sharp decline in the price of staple exports such as figs and currants and the wholesale replacement in some places of olive-groves by 1 vineyards. -

Australian Agricultural Company IS

INDEX Abbreviations A. A. Co.: Australian Agricultural Company I. S.: Indentured Servant Note: References are to letter numbers not page numbers. A. A. Co.: Annual Accounts of, 936; Annual James Murdoch, 797, 968; Hugh Noble, Report of, 1010; and letter of attorney 779; G. A. Oliver, 822; A. P. Onslow, empowering Lieutenant Colonel Henry 782; George T. Palmer, 789, 874; John Dumaresq to act as Commissioner of, Paul, 848; John Piper, senior, 799, 974; 1107; Quarterly Accounts of, 936; value of James Raymond, 995; separate, for supply property of at 3 April 1833, 980; see also of coal to Colonial Department and to stock in A. A. Co. Commissariat Department, 669, 725, 727; A. A. Co. Governor, London, see Smith, John: Benjamin Singleton, 889; William Smyth, A. A. Co. Stud, 706a, 898, 940d 759; Samuel Terry, 780; Thomas Walker, Aborigines: allegations of outrages against by 784, 811; William Wetherman, 917; T. B. Sir Edward Parry and others in employ of Wilson, 967; Sir John Wylde, 787, 976 A. A. Co., 989, 1011a, 1013; alleged offer ‘Act for preventing the extension of the of reward for heads of, 989; engagement of infectious disease commonly called the as guide for John Armstrong during survey, Scab in Sheep or Lambs’ (3 William IV No. 1025; and murder of James Henderson, 5, 1832) see Scab Act 906; number of, within limits of A. A. Co. Adamant: convicts on, 996, 1073 ‘s original grant, 715; threat from at Port advertisements; see under The Australian; Stephens, 956 Sydney Gazette; Sydney Herald; Sydney accidents, 764a Monitor accommodation: for A. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

Guy & Joe Lynch in Australasia

On Tasman Shores: Guy & Joe Lynch in Australasia MARTIN EDMOND University of Western Sydney The Tasman Sea, precisely defined by oceanographers, remains inchoate as a cultural area. It has, as it were, drifted in and out of consciousness over the two and a half centuries of permanent European presence here; and remains an almost unknown quantity to prehistory. Its peak contact period was probably the sixty odd years between the discovery of gold in Victoria and the outbreak of the Great War; when the coasts of New Zealand and Australia were twin shores of a land that shared an economy, a politics, a literature and a popular culture: much of which is reflected in the pages of The Bulletin from the 1880s until 1914. There was, too, a kind of hangover of the pre-war era and of the ANZAC experience into the 1920s; but after that the notional country sank again beneath the waves. Recovery of fragments from that lost cultural zone is a project with more than historical interest: each retrieval is a prospective act, contributing to the restoration of a world view which, while often occluded, has never really gone away. There is of course much which is irrecoverable now; but that is in itself a provocation; for a mosaic made out of dislocated pieces might disclose something unprecedented, neither existent in the past nor otherwise imaginable in the present: the lineaments of the new world, at once authentic and delusive, that so entranced the earliest explorers of the Antipodes. What follows, then, is an assembly of bits of one of those sets of fragments: the story of the Lynch brothers, Guy and Joe, a sculptor and an artist; and the milieu in which they lived.