In Memory of Doctor Pam Dahl-Helm Johnston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEM-Affinity Exhibition Publication Online PDF Here

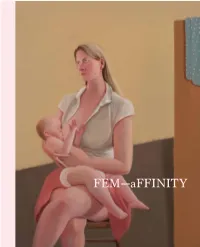

1 — FEM—aFFINITY — 2 FEM—aFFINITY Fulli Andrinopoulos / Jane Trengove Dorothy Berry / Jill Orr Wendy Dawson / Helga Groves Bronwyn Hack / Heather Shimmen Eden Menta / Janelle Low Lisa Reid / Yvette Coppersmith Cathy Staughton / Prudence Flint A NETS Victoria & Arts Project Australia touring exhibition, curated by Catherine Bell Cover Prudence Flint Feed 2019 oil on linen 105 × 90 cm Courtesy of the artist, represented by Australian Galleries, Melbourne BacK Cover Eden Menta & Janelle Low Eden and the Gorge 2019 inkjet print, ed. 1/5 100 × 80 cm Courtesy of the artists; Eden Menta is represented by Arts Project Australia, Melbourne — Co-published by: National Exhibitions Touring Support Victoria c/- The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia Federation Square PO Box 7259 Melbourne Vic 8004 netsvictoria.org.au and Arts Project Australia 24 High Street Northcote Vic 3070 artsproject.org.au — Design: Liz Cox, studiomono.co Copyediting & proofreading: Clare Williamson Printer: Ellikon Edition: 1000 ISBN: 978-0-6486691-0-4 Images © the artists 2019. Text © the authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia 2019. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors. No material, whether written or photographic, may be reproduced without the permission of the artists, authors, NETS Victoria and Arts Project Australia. Every effort has been made to ensure that any text and images in this publication have been reproduced with the permission of the artists or the appropriate authorities, wherever it is possible. 3 — Lisa Reid Not titled 2019 -

Incorporating Indigenous Knowledge in the Care of Threatened Species at Arakwal National Park

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge in the care of threatened species at Arakwal National Park Project 6.2.1 KEY MESSAGES • Scientists, Traditional • We have held planning • Over the past year, this Owners and Park staff and evaluation workshops project has supported are working together to to develop knowledge- a back-to-country manage the Byron Bay sharing protocols, priority workshop for local Orchid (Diuris byronensis) actions and measures Indigenous families, and its clay heath habitat of success to care for cultural burning in Arakwal National Park. these important areas. on the clay heath habitat and community engagement activities. What is the problem being tackled? The endangered Byron Bay Orchid (Diuris byronensis) is unique to Arakwal National Park. The orchid and its endangered clay heath habitat, which is an endangered ecological community, have important conservation and cultural values. Yet these values are threatened by wild fires, weeds, feral animals and the impact of thousands of tourists who visit this region throughout the year. Joint managers at Arakwal need to work together to ensure effective joint management of these important species and areas. Indigenous burning of clay heath was recently carried out for the first time in 30 years. Photo: Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation. Who is involved? Why is this important to the Bundjalung of Byron Bay People (Arakwal)? This project is a collaboration Local Traditional Owners are the Bundjalung of Byron Bay between Bundjalung people interested in the decisions and People (Arakwal) to look after of Byron Bay (Arakwal), outcomes achieved in this the things they think are most Arakwal joint Park Managers, protected area. -

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: The chapter considers the leadership of Ruby Langford Ginibi, whose writings recorded the history of the Bundjalung people of the Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales. She became prominent in national debates on Indigenous issues from the publication in 1988 of her autobiography, Don’t Take Your Love to Town until her death in 2011. Langford Ginibi was an effective voice in the attempt to persuade non-Aboriginal Australians to acknowledge the oppressive character of settler colonialism and its outcome in negative aspects of many Indigenous Australians’ lives in contemporary Australia. Above all, she drove understanding of the precariousness Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and the social wellbeing of their families when they left impoverished communities to seek waged work in far flung rural and in urban environments. Through her numerous publications, her research, public talks and interviews, Langford Ginibi made a major contribution to Australia that was recognized by numerous prestigious awards and an honorary doctorate. In 2012, a special issue of the Journal of the European Association of Studies on Australia commemorated her achievements. Key words: Aboriginal historians, Aboriginal writers, Indigenous rights, Bundjalung people, human rights, social justice In 1988 a Bundjalung woman, Ruby Langford (later Ruby Langford Ginibi), published her autobiography Don’t Take Your Love to Town to considerable applause, including the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Award for Literature.1 Encouraged that she had an audience open to the story of the fraught life situations of Indigenous people, Langford Ginibi continued to produce works that informed non-Indigenous Australians about the past experiences of her people until shortly before her death in October 2011. -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

[email protected] O

51 Lawson Crescent Acton Peninsula, Acton ACT 2601 GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 ABN 62 020 533 641 www.aiatsis.gov.au Environment and Communications References Committee The Senate Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Via email: [email protected] o·ear Committee Members Senate Inquiry into Australia's faunal extinction crisis AIATSIS Submission The Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) welcomes the opportunity to make a submission in support of the Senate Inquiry into Australia's faunal extinction crisis. AIATSIS would recommend the focus of this senate inquiry includes: consultation with traditional owner groups; native title corporations administering native title settlements and agreements bodies; Native Title Representative Bodies (NTRBs); Native Title Service Providers (NTSPs) and Aboriginal Land Councils: all of whom exercise responsibility for the management of the Indigenous Estate and large tracts of the National Reserve System. This critical consultation and engagement is to ensure that traditional knowledge and management is acknowledged as being an essential element in threatened species recovery, management and conservation. AIATSIS submits that acknowledging the totality of the Indigenous Estate and its interconnection with the National Reserve System is essential in terms of addressing the faunal extinction crisis across the content. Caring for Country programs, Indigenous Land and Sea Management Programs (ILSMPs) and Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) are achieving great success in terms of threatened species recovery and the eradication of feral pests and species. Please find attached the AIATSIS submission which is based upon 26 years of research and practice by AIATSIS in Indigenous cultural heritage and native title law. -

Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch Briefing Paper No 9/04 RELATED PUBLICATIONS • Aborigines, Land and National Parks in New South Wales by Stewart Smith, Briefing Paper No 2/97 • The Native Title Debate: Background and Current Issues by Gareth Griffith, Briefing Paper No 15/98 • Indigenous Issues in NSW by Talina Drabsch, Background Paper No 2/04 ISSN 1325-4456 ISBN 0 7313 1764 5 July 2004 © 2004 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Indigenous Australians and Land in New South Wales by Talina Drabsch NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Rowena Johns (BA (Hons), LLB), Research Officer, Law........................(02) 9230 2003 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research -

Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment a Guide for Tertiary Educators

Indigenous Knowledge in The Built Environment A Guide for Tertiary Educators David S Jones, Darryl Low Choy, Richard Tucker, Scott Heyes, Grant Revell & Susan Bird Support for the production of this publication has been 2018 provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this report do ISBN not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government 978-1-76051-164-7 [PRINT], Department of Education and Training. 978-1-76051-165-4 [PDF], With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and 978-1-76051-166-1 [DOCX] where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Citation: International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Jones, DS, D Low Choy, R Tucker, SA Heyes, G Revell & S Bird by-sa/4.0/ (2018), Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment: A Guide The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on for Tertiary Educators. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links Department of Education and Training. provided) as is the full legal code for the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License http:// Warning: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following document may contain images and names of Requests and inquiries concerning these rights should be deceased persons. addressed to: Office for Learning and Teaching A Note on the Project’s Peer Review Process: Department of Education The content of this teaching guide has been independently GPO Box 9880, peer reviewed by five Australian academics that specialise Location code N255EL10 in the teaching of Indigenous knowledge systems within the Sydney NSW 2001 built environment professions, two of which are Aboriginal [email protected] academics and practitioners. -

Arakwal National Park Plan of Managementdownload

Acknowledgments This plan could not be written without the approval and support of the Arakwal Elders and people. The Arakwal Elders approved David Edwards (former Senior Ranger, NPWS) to be the writer of this plan but wanted him to talk to as many people as possible. David worked closely with the Arakwal National Park Management Committee consisting of Yvonne Stewart (Committee Chairperson and Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation representative), Aunty Lorna Kelly (dec) (Elder and Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation representative), Aunty Linda Vidler (Elder and Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation representative), Norman Graham (Ranger and Committee Secretary, NPWS), Mark Johnston (Regional Manager, Northern Rivers Region, NPWS), Sue Walker (Area Manager, Byron Coast Area, NPWS) David Murray (former Area Manager, Richmond River Area, NPWS), and Mayor Jan Barham (Byron Shire Council). Aunty Dulcie Nicholls (Elder and Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation Representative) and other members of the Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation and the wider Byron Bay community also provided valuable input to this plan of management. Donna Turner (former Planning Officer, Northern Branch, NPWS) and David Major (former Cultural Policy Officer, NPWS) also assisted in the preparation of this plan. Valuable information and comments were provided by other NPWS staff of the Northern Rivers Region and members of the public. All art in this plan is by Byron Bay Arakwal artist Sean Kay. Inquiries about this plan of management should be directed to the NPWS, Byron Coast Area, PO Box 127, Byron Bay 2481 or by telephone on (02) 6685 8565. February 2007 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Part of the Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) Copyright 2004: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment ISBN 1 74122 243 5 Jingi wahlu widtha .(Welcome to Country) This plan talks about a special part of Byron Bay Arakwal Country that is now within Arakwal National Park. -

Bundjalung and Anangu Identity and Autonomy

Aboriginal Studies Curriculum Support Stage 5 Bundjalung and Anangu identity and autonomy 1 Aboriginal Studies – Curriculum Support, Stage 5 Bundjalung and Anangu – identity and autonomy Teacher planning starts here Students will Why does the learning matter? demonstrate their To enable students to gain knowledge and understanding of knowledge of Aboriginal peoples of Australia, their cultures and lifestyles, and to express this knowledge Aboriginality, the impacts of invasion and resilience of Aboriginal people to retain identity and Target syllabus outcomes autonomy Outcomes 5.1–5.11 Major assessment task Parts A and B (see below). Students contribute to a classroom portfolio that will record experiences of the Bundjalung nation (their local Aboriginal community) from pre-contact to contemporary times. Part C – Reflection portfolio. Students consider the range of classroom activities for learning that they have undertaken. They will select from these and for each write a brief report (300 words) explaining how this activity developed their understanding of contemporary Aboriginal identity and autonomy. Assessment for learning task 6 Assessment for learning task 8 Human rights, self-determination and Return of land. autonomy Major assessment Part B: Community resilience Students to research the various Assessment for learning task 7 programs and resources that the Bundjalung people have developed Resistance. which assist them to retain a unique identity. Students select one of the three options outlined in the assessment task description and present a Case Study Assessment for learning task 3 report of about 650 words. Adaptations and celebrations Major assessment Part A: Bundjalung identity Each student produces two or more articles Assessment for learning task 5 which relate to Bundjalung identity. -

Download LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Brochure

LOOK. LOOK AGAIN CAMPUS PARTNER LOOK. OUTSKIRTS Outskirts: feminisms along the edge is a feminist cultural studies journal produced through the discipline of Gender Studies at UWA. Published LOOK AGAIN twice yearly, the journal presents new and challenging critical material from a range of disciplinary perspectives and feminist topics, to discuss and contest contemporary and historical issues involving women and feminisms. An initiative of postgraduate students at UWA, Outskirts began as a printed magazine in 1996 before going online in 1998 under the editorship of Delys Bird and then Alison Bartlett since 2006. Outskirts will be publishing selected papers from the symposium Are we there yet? in 2013. GENDER STUDIES Gender Studies is an interdisciplinary area that examines the history and politics of gender relations. Academic staff teach units about the history of ideas of gender, intersections with race, class and sexuality, and the operations of social power. They are also engaged in a range of scholarly research activities around the history and politics of gender relations, sexualities, cinema, maternity, witchcraft, masculinities, activism, intersections of race, class and gender, feminist theory and the body. While some graduates have gone on to specialise in gender- related areas such as equity and diversity, policy development, social justice and workplace relations, most apply their skills in the broader fields of communications, education, public service, research occupations and professional practice. Gender Studies staff are participating in the public programs and symposium associated with this exhibition. LOOK. LOOK AGAIN Above: Sangeeta Sandrasegar, Untitled (Self portrait of Prudence), 2009 felt, glass beads, sequins, cotton, 88 x 60 cm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Courtesy of the artist The Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery would like to extend sincere thanks to Cover: Nora Heysen, Gladioli, 1933, oil on canvas, 63 x 48.5 cm all the artists whose work is included in this exhibition. -

TAFE NSW Innovate Reconciliation Action Plan 2020 -2022

Innovate Reconciliation Action Plan 2020–2022 November 2020 – November 2022 tafensw.edu.au Acknowledgement of Country TAFE NSW acknowledges Aboriginal Peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which our campuses are located and where we conduct our business. We pay our respects to past, present, and emerging Elders, and we are committed to honouring Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ unique Cultural and spiritual relationships to the land, waters, and seas, as well as their rich contribution to society. We recognise that Aboriginal Cultures and Communities form the foundation of Cultural diversity within New South Wales. Hundreds of Cultures, Languages, and Kinship structures have long been embedded in the lands of Aboriginal Countries throughout the state. We acknowledge and celebrate these diverse Traditions, Customs, and Cultures that have existed for more than 60,000 years. TAFE NSW is committed to support Closing the Gap targets for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, by identifying opportunities to increase their learning potential and by helping them to achieve their goals and flourish. TAFE NSW will continue to value Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultures and promote their rights and interests. In doing so, we acknowledge the wrongs of the past, respect the Cultural diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and commit to embedding equality and equity throughout all areas of TAFE NSW by integrating inclusive and innovative opportunities that will result in stronger relationships built on respect and trust. Disclaimer: For the purposes of this document, use of the term ‘Aboriginal’ is inclusive of Torres Strait Islander Peoples and has been written and formated in accordance with the TAFE NSW Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protocols for Appropriate Language and Referencing Guide. -

BOOKBINDING .;'Ft1'

• BALOS BOOKBINDING .;'fT1'. I '::1 1 I't ABORIGINAL SONGS FROM THE BUNDJALUNG AND GIDABAL AREAS OF SOUTH-EASTERN AUSTRALIA by MARGARET JANE GUMMOW A thesis submitted in fulfihnent ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department ofMusic University of Sydney July 1992 (0661 - v£6T) MOWWnO UllOI U:lpH JO .uOW:lW :lip Ol p:ll1l:>W:l<J ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I wish to express my most sincere thanks to all Bundjalung and Gidabal people who have assisted this project Many have patiently listened to recordings ofold songs from the Austra1ian Institute ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, sung their own songs, translated, told stories from their past, referred me to other people, and so on. Their enthusiasm and sense ofurgency in the project has been a continual source of inspiration. There are many other people who have contributed to this thesis. My supervisor, Dr. Allan Marett, has been instrumental in the compilation of this work. I wish to thank him for his guidance and contributions. I am also indebted to Dr. Linda Barwick who acted as co-supervisor during part of the latter stage of my candidature. I wish to thank her for her advice on organising the material and assistance with some song texts. Dr. Ray Keogh meticulously proofread the entire penultimate draft. I wish to thank him for his suggestions and support. Research was funded by a Commonwealth Postgraduate Research Award. Field research was funded by the Austra1ian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Several staff members at AlATSIS have been extremely helpful.