Fighting Game Primer (Super Book Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Will to Keep Winning Download Free (EPUB, PDF)

The Will To Keep Winning Download Free (EPUB, PDF) "No matter what your life plan is, no matter what your project, a close reading of the life and thoughts of Daigo will give you deep insight into how to be successful and help you reach your goals."—Frank Lantz, Director, NYU Game Center"When Daigo wins, he does not simply elevate his own status, he elevates the entire genre alongside him. Through his play, and through his approach to life, Daigo changes the way people think about the game, and inspires even his enemies to new heights. This is what separates a mere winner from an all-time great."—Seth Killian, Lead Game Designer at Riot Games"Daigo and I started an international journey to showcase Street Fighter competition in 1998. Today, he is the Grand Master of fighting games and true inspiration to players worldwide.â€â€”Alex Valle, CaliPower, Mr. Street Fighter“It’s almost impossible to overstate the significance of The Beast for the practice and culture of gaming; as Bruce Lee was for the Martial Arts, so Daigo Umehara is for Fighting Games.â€â€”Prof. Chris Goto-Jones, Professor of Comparative Philosophy & Political Thought, Leiden University"I’m a professional fighting gamer. I was first crowned World Champion at seventeen in 1998, and I was recognized as “the most successful player in major tournaments of Street Fighter†by Guinness World Records in August 2010.This is my chance to tell you how I became World Champion and share insights as only a multiple time World Champion can. -

Street Fighter

STREET FIGHTER by Luis Filipe Based on Capcom's videogame "Street Fighter II" Copyright © 2019 This is a fan script [email protected] OVER BLACK. All we hear is the excited CHEER of a crowd. Hundreds of voices roaring in unison, teasing something to come. Under those voices, there is also the rhythmic sound of TRAMPLES on the floor that sound like drums. CUT TO: INT. CORRIDOR - NIGHT A dirty, dimly lit corridor. A few meters ahead, a beam of light leaks through a door that gives access to another scenario. Standing in the corridor hidden in total shadow, a barefoot MAN attired in a white karate gi uniform tightens a black martial arts BELT. We do not see his face. The cheer continues, seeming to be coming from beyond that door in the hallway. After putting on the belt, the man takes a pair of RED GLOVES from his duffel bag, which is on a bench beside him. He wears them calmly. Finally, he also grabs a RED HEADBAND from the bag and ties it around his head. All this is almost ritualistic for him. When completed, the mysterious man walks toward the corridor door where comes the intense light. INT. STREET FIGHTER ARENA - NIGHT A large warehouse-like room. Wooden boxes surround the boundaries of the fighting area. And behind these boxes are the spectators, some sit in stands and others stand on feet. Our mysterious man comes in, revealing his face for the first time: RYU. A Japanese experienced martial artist. The audience goes wild to see him there. -

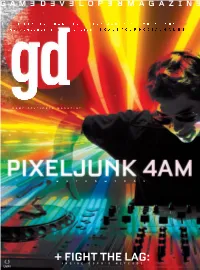

Game Developers Agree: Lag Kills Online Multiplayer, Especially When You’Re Trying to Make Products That Rely on Timing-Based CO Skill, Such As Fighting Games

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO9 SEPTEMBER 2012 INSIDE: SCALE YOUR SOCIAL GAMES postmortem BER 9 m 24 PIXELJUNK 4AM How do you invent a new musical instrument? PIXELJUNK 4AM turned PS3s everywhere into music-making machines and let players stream E 19 NU their performances worldwide. In this postmortem, lead designer Rowan m Parker walks us through the ups (Move controls, online streaming), the LU o downs (lack of early direction, game/instrument duality), and why you V need to have guts when you’re reinventing interactive music. By Rowan Parker features NTENTS.0912 7 FIGHT THE LAG! Nine out of ten game developers agree: Lag kills online multiplayer, especially when you’re trying to make products that rely on timing-based co skill, such as fighting games. Fighting game community organizer Tony Cannon explains how he built his GGPO netcode to “hide” network latency and make online multiplayer appetizing for even the most picky players. By Tony Cannon 15 SCALE YOUR ONLINE GAME Mobile and social games typically rely on a robust server-side backend—and when your game goes viral, a properly-architected backend is the difference between scaling gracefully and being DDOSed by your own players. Here’s how to avoid being a victim of your own success without blowing up your server bill. By Joel Poloney 20 LEVEL UP YOUR STUDIO Fix your studio’s weakest facet, and it will contribute more to your studio’s overall success than its strongest facet. Production consultant Keith Fuller explains why it’s so important to find and address your studio’s weaknesses in the results of his latest game production survey. -

Download the Catalog

WE SERVE BUSINESSES OF ALL SIZES WHO WE ARE We are an ambitious laser tag design and manufacturing company with a passion for changing the way people EXPERIENCE LIVE-COMBAT GAMING. We PROVIDE MANUFACTURING and support to businesses both big or small, around the world! With fresh thinking and INNOVATIVE GAMING concepts, our reputation has made us a leader in the live-action gaming space. One of the hallmarks of our approach to DESIGN & manufacturing is equipment versatility. Whether operating an indoor arena, outdoor battleground, mobile business, or a special entertainment OUR PRODUCTS HAVE THE HIGHEST REPLAY attraction our equipment can be CUSTOMIZED TO FIT your needs. Battle Company systems will expand your income opportunities and offer possibilities where the rest of the industry can only provide VALUE IN THE LASER TAG INDUSTRY limitations. Our products are DESIGNED AND TESTED at our 13-acre property headquarters. We’ve put the equipment into action in our 5,000 square-foot indoor laser tag facility as well as our newly constructed outdoor battlefield. This is to ensure the highest level of design quality across the different types of environments where laser tag is played. Using Agile development methodology and manufacturing that is ISO 9001 CERTIFIED, we are the fastest manufacturer in the industry when it comes to bringing new products and software to market. Battle Company equipment has a strong competitive advantage over other brands and our COMMITMENT TO R&D is the reason why we are leading the evolution of the laser tag industry! 3 OUT OF 4 PLAYERS WHO USE BATTLE COMPANY BUSINESSES THAT CHOOSE US TO POWER THEIR EXPERIENCE EQUIPMENT RETURN TO PLAY AGAIN! WE SERVE THE MILITARY 3 BIG ATTRACTION SMALL FOOTPRINT Have a 10ft x 12.5ft space not making your facility much money? Remove the clutter and fill that area with the Battle Cage. -

Adjustment Description Alterations to V-Shift's

Adjustment Description Abilities granting invincibility or armor from the 1st frame, as well as low- risk or high-return moves invincible to throws have all been adjusted to have less effective throw invincibility. Alterations to V-Shift's Considering V-Shift's offensive and defensive capabilities, normal throws offensive/defensive should have enough impact to reliably handle V-Shifts, but characters with capabilities the invincible abilities mentioned above had an easy way to deal with throws and strikes. This gave their defense such a strong advantage that offensive opponents struggled against it. These adjustments seek to correct this issue. These general adjustments are a continuation of previous adjustments. Improvements to While V-Skills and V-Triggers have already been adjusted overall, players infrequently used V-Triggers tend to use one V-Skill and V-Trigger over the other, so we have further and V-Skills strengthened the techniques themselves and the moves that rely on their input. Some characters have been rebalanced in light of previous adjustments. We have buffed characters who were lacking in strength or who were Rebalancing of some largely left alone in previous adjustments. characters Characters with downward adjustments have not had their moves altered significantly; rather, the risks and returns of moves have been properly balanced. Balance Change Overview We've adjusted Nash's close-quarters attack, standing light kick, to yield more of an advantage on hit, and we have further improved Nash's impressive mid to long-distance combat. Standing light kick was previously adjusted to have faster start-up and to be easier to land, but we noticed that it didn't grant the same rewards as it did for other characters. -

Application of Retrograde Analysis on Fighting Games

Application of Retrograde Analysis on Fighting Games Kristen Yu Nathan R. Sturtevant Computer Science Department Computer Science Department University of Denver University of Alberta Denver, USA Edmonton, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—With the advent of the fighting game AI competition, optimal AI. This work opens the door for deeper study of there has been recent interest in two-player fighting games. both optimal and suboptimal play, as well as options related Monte-Carlo Tree-Search approaches currently dominate the to game design, where the impact of design choices in a game competition, but it is unclear if this is the best approach for all fighting games. In this paper we study the design of two- can be studied. player fighting games and the consequences of the game design on the types of AI that should be used for playing the game, as II.R ELATED WORK well as formally define the state space that fighting games are A variety of approaches have been used for fighting game AI based on. Additionally, we also characterize how AI can solve the in both industry and academia. One approach in industry has game given a simultaneous action game model, to understand the characteristics of the solved AI and the impact it has on game game AI being built using N-grams as a prediction algorithm design. to help the AI become better at playing the game [30]. Another common technique is using decision trees to model I.I NTRODUCTION AI behavior [30]. This creates a rule set with which an agent can react to decisions that a player makes. -

Cgcopyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe

c Copyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: James R. Lee, Chair Zoran Popovi´c,Chair Anna Karlin Program Authorized to Offer Degree: UW Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James R. Lee CSE Professor Zoran Popovi´c CSE Game balancing is the fine-tuning phase in which a functioning game is adjusted to be deep, fair, and interesting. Balancing is difficult and time-consuming, as designers must repeatedly tweak parameters and run lengthy playtests to evaluate the effects of these changes. Only recently has computer science played a role in balancing, through quantitative balance analysis. Such methods take two forms: analytics for repositories of real gameplay, and the study of simulated players. In this work I rectify a deficiency of prior work: largely ignoring the players themselves. I argue that variety among players is the main source of depth in many games, and that analysis should be contextualized by the behavioral properties of players. Concretely, I present a formalization of diverse forms of game balance. This formulation, called `restricted play', reveals the connection between balancing concerns, by effectively reducing them to the fairness of games with restricted players. Using restricted play as a foundation, I contribute four novel methods of quantitative balance analysis. I first show how game balance be estimated without players, using sim- ulated agents under algorithmic restrictions. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Game List of Game Elf 619 in 1

Game list of game elf 001. King of Fighters 2003, The 041. Samurai Shodown IV 002. King of Fighters 2004 Ultra 042. Fighters Swords Plus, The 043. Fatal Fury 003. King of Fighters 2000, The 044. Fatal Fury 2 004. KOF 2002 Magic Plus 3 045. Fatal Fury 3 005. KOF 2002 Magic Plus 2 046. Fatal Fury Special 006. Rage of the Dragons 047. Real Bout Fatal Fury Special 007. SNK vs Capcom Plus 048. Real Bout Fatal Fury 008. Cadillacs and Dinosaurs 049. Real Bout Fatal Fury 2 009. Cadillacs and Dinosaurs Plus 050. Art of Fighting 010. King of Fighters 2004 Plus / 051. Art of Fighting 2 Hero, The 052. Art of Fighting 3 011. KOF 10th Extra Plus 053. Breakers 012. King of Gladiator 054. Breakers Revenge 013. Matrimelee 055. World Heroes 2 014. Double Dragon 056. World Heroes 2 Jet 015. KOF 2002 057. World Heroes Perfect 016. KOF 2002 Plus 058. Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of 017. KOF 2002 Super Doom 018. Samurai Shodown V Special 059. Dungeons & Dragons: Shadow 019. KOF 98 ○ over Mystara 020. KOF 99 - Millennium Battle 060. X-Men Vs. Street Fighter 021. KOF 97 061. X-Men: Children of the Atom 022. KOF 97 Plus 062. Vampire Savior 023. KOF 94 063. Vampire Savior 2: The Lord of 024. KOF 95 Vampire 025. KOF 96 064. Vampire Hunter: 026. Operation Ragnagard Darkstalkers' Revenge 027. Galaxy Fight 065. Vampire Hunter 2: 028. Michael Jackson's Moonwalker Darkstalkers Revenge 029. Karate Blazers 066. Super Street Fighter II X 030. The Punisher 067. -

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer. -

Street Fighter X Tekken Pc Download Street Fighter X Tekken

street fighter x tekken pc download Street Fighter X Tekken. The long awaited dream match-up between the two leaders in the fighting genre becomes a reality. Street Fighter X Tekken delivers the ultimate tag team match up featuring iconic characters from each franchise, and one of the most robust character line ups in fighting game history. With the addition of new gameplay mechanics, the acclaimed fighting engine from Street Fighter IV has been refined to suit the needs of both Street Fighter and Tekken players alike. DREAM MATCH UP � Dozens of playable characters including Hugo, Ibuki, Poison, Dhalsim, Ryu, Ken, Guile, Abel, and Chun-Li from Street Fighter as well as Raven, Kuma, Yoshimitsu, Steve, Kazuya, Nina, King, Marduk, and Bob from Tekken. REAL-TIME TAG BATTLE � Fight as a team of two and switch between characters strategically. FAMILIAR CONTROLS � In Street Fighter X Tekken, controls will feel familiar for fans of both series. JUGGLE SYSTEM � Toss your foes into Tekken-style juggles with Street Fighter X Tekken�s universal air launching system. CROSS ASSAULT � By using the Cross Gauge, a player can activate Cross Assault and attack with both of their characters at the same time. SUPER ART � Using the Cross Gauge you can immediately unleash a Super Art. Ryu�s famed Shinku Hadoken, Kazuya�s Devil Beam as well as the Tekken characters all have original Super Art techniques. ROBUST ONLINE MODES � In addition to the online features from Super Street Fighter IV, Street Fighter X Tekken features totally upgraded online functionality and some new surprises. Game mode: single / multiplayer Multiplayer mode: Internet Player counter: 1-2. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle