The Politics of Partying: Electronic Dance Music As Collectivist Experimentation and Subversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and the Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan Otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl Ld

The New Psychedelic Culture: LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and The Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl ld. by ROBERT B. MILLMAN, MD and RELATIONSHIPOFPSYCHOPATHOLOGYTOPATTERNS ANN BORDWINE BEEDER, MD OFUSE Hallucinogens and psychedelics are terms sychedelics have been used since an- and synthetic compounds primarily derived cient times in diverse cultures as an from indoles and substituted phenethylamines i/ integral part of religious or recrea- usedthat induceto describechangesbothinthethoughtnaturallyor perception.occurring tional ceremony and ritual. The rela- The most frequently used naturally occurring tionship of LSD and other psychedelics to West- substances in this class include mescaline ern culture dates from the development of the from the peyote plant, psilocybin from "magic drug in 1938 by the chemist Albert Hoffman. I mushrooms," and ayuahauscu (yag_), a root LSD and naturally occurring psychedelics such indigenous to South America. The synthetic as mescaline and psilocybin have been associ- drugs most frequently used are MDMA ('Ec- I ated in modem times with a society that re- stasy'), PCP (phencyclidine), and ketamine. jected conventional values and sought transcen- Hundreds of analogs of these compounds are dent meaning and spirituality in the use of known to exist. Some of these obscure com- drugs and the association with other users, pounds have been termed 'designer drugs? During the 1960s the psychedelics were most Perceptual distortions induced by hallu- oi%enused by individuals or small groups on an cinogen use are remarkably variable and de- intermittent basis to _celebrate' an event or to pendent on the influence of set and setting. participate in a quest for spiritual or cultural Time has been described as _standing still" by values, peoplewho spend long periodscontemplating Current use varies from the rare, perhaps perceptual, visual, or auditory stimuli. -

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy Martin J. Zeilinger York University, Canada [email protected] Abstract This essay considers how chipmusic, a fairly recent form of alternative electronic music, deals with the impact of contemporary intellectual property regimes on creative practices. I survey chipmusicians’ reusing of technology and content invoking the era of 8-bit video games, and highlight points of contention between critical perspectives embodied in this art form and intellectual property policy. Exploring current chipmusic dissemination strategies, I contrast the art form’s links to appropriation-based creative techniques and the ‘demoscene’ amateur hacking culture of the 1980s with the chiptune community’s currently prevailing reliance on Creative Commons licenses for regulating access. Questioning whether consideration of this alternative licensing scheme can adequately describe shared cultural norms and values that motivate chiptune practices, I conclude by offering the concept of a moral economy of appropriation-based creative techniques as a new framework for understanding digital creative practices that resist conventional intellectual property policy both in form and in content. Keywords: Chipmusic, Creative Commons, Moral Economy, Intellectual Property, Demoscene Introduction The chipmusic community, like many other born-digital creative communities, has a rich tradition of embracing and encouraged open access, collaboration, and sharing. It does not like to operate according to the logic of informational capital and the restrictive enclosure movements this logic engenders. The creation of chipmusic, a form of electronic music based on the repurposing of outdated sound chip technology found in video gaming devices and old home computers, centrally involves the reworking of proprietary cultural materials. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Videogame Music: Chiptunes Byte Back?

Videogame Music: chiptunes byte back? Grethe Mitchell Andrew Clarke University of East London Unaffiliated Researcher and Institute of Education 78 West Kensington Court, University of East London, Docklands Campus Edith Villas, 4-6 University Way, London E16 2RD London W14 9AB [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Musicians and sonic artists who use videogames as their This paper will explore the sonic subcultures of videogame medium or raw material have, however, received art and videogame-related fan art. It will look at the work of comparatively little interest. This mirrors the situation in art videogame musicians – not those producing the music for as a whole where sonic artists are similarly neglected and commercial games – but artists and hobbyists who produce the emphasis is likewise on the visual art/artists.1 music by hacking and reprogramming videogame hardware, or by sampling in-game sound effects and music for use in It was curious to us that most (if not all) of the writing their own compositions. It will discuss the motivations and about videogame art had ignored videogame music - methodologies behind some of this work. It will explore the especially given the overlap between the two communities tools that are used and the communities that have grown up of artists and the parallels between them. For example, two around these tools. It will also examine differences between of the major videogame artists – Tobias Bernstrup and Cory the videogame music community and those which exist Archangel – have both produced music in addition to their around other videogame-related practices such as modding gallery-oriented work, but this area of their activity has or machinima. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

A Brief History of Electronic Music

A Brief History of Electronic Music 1: 1896-1945 The first twenty-five years of the life of the archetypal modern artist, Pablo Picasso - who was born in 1881 - witnessed the foundation of twentieth century technology for war and peace alike: the recoil operated machine gun (1882), the first synthetic fibre (1883), the Parsons steam turbine (1884), coated photographic paper (1885), the Tesla electric motor, the Kodak box camera and the Dunlop pneumatic tyre (1888), cordite (1889), the Diesel engine (1892), the Ford car (1893), the cinematograph and the gramophone disc (1894). In 1895, Roentgen discovered X-rays, Marconi invented radio telegraphy, the Lumiere brothers developed the movie camera, the Russian Konstantin Tsiolkovsky first enunciated the principle of rocket drive, and Freud published his fundamental studies on hysteria. And so it went: the discovery of radium, the magnetic recording of sound, the first voice radio transmissions, the Wright brothers first powered flight (1903), and the annus mirabilis of theoretical physics, 1905, in which Albert Einstein formulated the Special Theory of Relativity, the photon theory of light, and ushered in the nuclear age with the climactic formula of his law of mass-energy equivalence, E = mc2. One did not need to be a scientist to sense the magnitude of such changes. They amounted to the greatest alteration of man's view of the universe since Isaac Newton. - Robert Hughes (1981) In 1896 Thaddeus Cahill patented an electrically based sound generation system. It used the principle of additive tone synthesis, individual tones being built up from fundamentals and overtones generated by huge dynamos. -

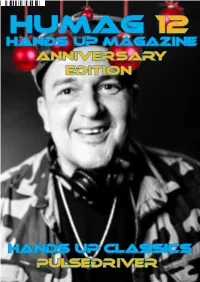

Hands up Classics Pulsedriver Hands up Magazine Anniversary Edition

HUMAG 12 Hands up Magazine anniversary Edition hANDS Up cLASSICS Pulsedriver Page 1 Welcome, The time has finally come, the 12th edition of the magazine has appeared, it took a long time and a lot has happened, but it is done. There are again specials, including an article about pulsedriver, three pages on which you can read everything that has changed at HUMAG over time and how the de- sign has changed, one page about one of the biggest hands up fans, namely Gabriel Chai from Singapo- re, who also works as a DJ, an exclusive interview with Nick Unique and at the locations an article about Der Gelber Elefant discotheque in Mühlheim an der Ruhr. For the first time, this magazine is also available for download in English from our website for our friends from Poland and Singapore and from many other countries. We keep our fingers crossed Richard Gollnik that the events will continue in 2021 and hopefully [email protected] the Easter Rave and the TechnoBase birthday will take place. Since I was really getting started again professionally and was also ill, there were unfortu- nately long delays in the publication of the magazi- ne. I apologize for this. I wish you happy reading, Have a nice Christmas and a happy new year. Your Richard Gollnik Something Christmas by Marious The new Song Christmas Time by Mariousis now available on all download portals Page 2 content Crossword puzzle What is hands up? A crossword puzzle about the An explanation from Hands hands up scene with the chan- Up. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

The Wiki Music Dataset: a Tool for Computational Analysis of Popular Music

The Wiki Music dataset: A tool for computational analysis of popular music Fabio Celli Profilio Company s.r.l. via sommarive 18, 38123 Trento, Italy Email: fabio@profilio.co Abstract—Is it possible use algorithms to find trends in monic and timbral properties that brought changes in music the history of popular music? And is it possible to predict sound around 1964, 1983 and 1991 [14]. Beside these research the characteristics of future music genres? In order to answer fields, there is a trend in the psychology of music that studies these questions, we produced a hand-crafted dataset with the how the musical preferences are reflected in the dimensions intent to put together features about style, psychology, sociology of personality [11]. From this kind of research emerged the and typology, annotated by music genre and indexed by time MUSIC model [20], which found that genre preferences can and decade. We collected a list of popular genres by decade from Wikipedia and scored music genres based on Wikipedia be decomposed into five factors: Mellow (relaxed, slow, and ro- descriptions. Using statistical and machine learning techniques, mantic), Unpretentious, (easy, soft, well-known), Sophisticated we find trends in the musical preferences and use time series (complex, intelligent or avant-garde), Intense (loud, aggressive, forecasting to evaluate the prediction of future music genres. and tense) and Contemporary (catchy, rhythmic or danceable). Is it possible to find trends in the characteristics of the genres? Keywords—Popular Music, Computational Music analysis, And is it possible to predict the characteristics of future genres? Wikipedia, Natural Language Processing, dataset To answer these questions, we produced a hand-crafted dataset with the intent to put together MUSIC, style and sonic features, I.