AS Revision Test – Particle Physics and Electricity – the Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interactions of Antiprotons with Atoms and Molecules

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Department of Energy Publications U.S. Department of Energy 1988 INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES Mitio Inokuti Argonne National Laboratory Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub Part of the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Inokuti, Mitio, "INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES" (1988). US Department of Energy Publications. 89. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub/89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Energy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Department of Energy Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. /'Iud Tracks Radial. Meas., Vol. 16, No. 2/3, pp. 115-123, 1989 0735-245X/89 $3.00 + 0.00 Inl. J. Radial. Appl .. Ins/rum., Part D Pergamon Press pic printed in Great Bntam INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES* Mmo INOKUTI Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois 60439, U.S.A. (Received 14 November 1988) Abstract-Antiproton beams of relatively low energies (below hundreds of MeV) have recently become available. The present article discusses the significance of those beams in the contexts of radiation physics and of atomic and molecular physics. Studies on individual collisions of antiprotons with atoms and molecules are valuable for a better understanding of collisions of protons or electrons, a subject with many applications. An antiproton is unique as' a stable, negative heavy particle without electronic structure, and it provides an excellent opportunity to study atomic collision theory. -

1.1. Introduction the Phenomenon of Positron Annihilation Spectroscopy

PRINCIPLES OF POSITRON ANNIHILATION Chapter-1 __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1.1. Introduction The phenomenon of positron annihilation spectroscopy (PAS) has been utilized as nuclear method to probe a variety of material properties as well as to research problems in solid state physics. The field of solid state investigation with positrons started in the early fifties, when it was recognized that information could be obtained about the properties of solids by studying the annihilation of a positron and an electron as given by Dumond et al. [1] and Bendetti and Roichings [2]. In particular, the discovery of the interaction of positrons with defects in crystal solids by Mckenize et al. [3] has given a strong impetus to a further elaboration of the PAS. Currently, PAS is amongst the best nuclear methods, and its most recent developments are documented in the proceedings of the latest positron annihilation conferences [4-8]. PAS is successfully applied for the investigation of electron characteristics and defect structures present in materials, magnetic structures of solids, plastic deformation at low and high temperature, and phase transformations in alloys, semiconductors, polymers, porous material, etc. Its applications extend from advanced problems of solid state physics and materials science to industrial use. It is also widely used in chemistry, biology, and medicine (e.g. locating tumors). As the process of measurement does not mostly influence the properties of the investigated sample, PAS is a non-destructive testing approach that allows the subsequent study of a sample by other methods. As experimental equipment for many applications, PAS is commercially produced and is relatively cheap, thus, increasingly more research laboratories are using PAS for basic research, diagnostics of machine parts working in hard conditions, and for characterization of high-tech materials. -

ANTIPROTON and NEUTRINO PRODUCTION ACCELERATOR TIMELINE ISSUES Dave Mcginnis August 28, 2005

ANTIPROTON AND NEUTRINO PRODUCTION ACCELERATOR TIMELINE ISSUES Dave McGinnis August 28, 2005 INTRODUCTION Most of the accelerator operating period is devoted to making antiprotons for the Collider program and accelerating protons for the NUMI program. While stacking antiprotons, the same Main Injector 120 GeV acceleration cycle is used to accelerate protons bound for the antiproton production target and protons bound for the NUMI neutrino production target. This is designated as Mixed-Mode operations. The minimum cycle time is limited by the time it takes to fill the Main Injector with two Booster batches for antiproton production and five Booster batches for neutrino production (7 x 0.067 seconds) and the Main Injector ramp rate (~ 1.5 seconds). As the antiproton stack size grows, the Accumulator stochastic cooling systems slow down which requires the cycle time to be lengthened. The lengthening of the cycle time unfortunately reduces the NUMI neutrino flux. This paper will use a simple antiproton stacking model to explore some of the tradeoffs between antiproton stacking and neutrino production. ACCUMULATOR STACKTAIL SYSTEM After the target, antiprotons are injected into the Debuncher ring where they undergo a bunch rotation and are stochastically pre-cooled for injection into the Accumulator. A fresh beam pulse injected into the Accumulator from the Debuncher is merged with previous beam pulses with the Accumulator StackTail system. This system cools and decelerates the antiprotons until the antiprotons are captured by the core cooling systems as shown in Figure 1. The antiproton flux through the Stacktail system is described by the Fokker –Plank equation ∂ψ ∂φ = − (1) ∂t ∂E where φ the flux of particles passing through the energy E and ψ is the particle density of the beam at energy E. -

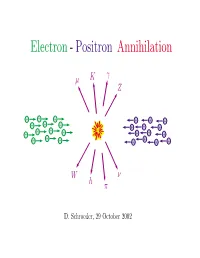

Electron - Positron Annihilation

Electron - Positron Annihilation γ µ K Z − − − + + + − − − + + + − − − − + + + − − − + + + + W ν h π D. Schroeder, 29 October 2002 OUTLINE • Electron-positron storage rings • Detectors • Reaction examples e+e− −→ e+e− [Inventory of known particles] e+e− −→ µ+µ− e+e− −→ q q¯ e+e− −→ W +W − • The future:Linear colliders Electron-Positron Colliders Hamburg Novosibirsk 11 GeV 12 GeV 47 GeV Geneva 200 GeV Ithaca Tokyo Stanford 12 GeV 64 GeV 8 GeV 12 GeV 30 GeV 100 GeV Beijing 12 GeV 4 GeV Size (R) and Cost ($) of an e+e− Storage Ring βE4 $=αR + ( E = beam energy) R d $ βE4 Find minimum $: 0= = α − dR R2 β =⇒ R = E2, $=2 αβ E2 α SPEAR: E = 8 GeV, R = 40 m, $ = 5 million LEP: E = 200 GeV, R = 4.3 km, $ = 1 billion + − + − Example 1: e e −→ e e e− total momentum = 0 θ − total energy = 2E e e+ Probability(E,θ)=? e+ E-dependence follows from dimensional analysis: density = ρ− A density = ρ+ − + × 2 Probability = (ρ− ρ+ − + A) (something with units of length ) ¯h ¯hc When E m , the only relevant length is = e p E 1 =⇒ Probability ∝ E2 at SPEAR Augustin, et al., PRL 34, 233 (1975) 6000 5000 4000 Ecm = 4.8 GeV 3000 2000 Number of Counts 1000 Theory 0 −0.8 −0.40 0.40.8 cos θ Prediction for e+e− −→ e+e− event rate (H. J. Bhabha, 1935): event dσ e4 1 + cos4 θ 2 cos4 θ 1 + cos2 θ ∝ = 2 − 2 + rate dΩ 32π2E2 4 θ 2 θ 2 cm sin 2 sin 2 Interpretation of Bhabha’sformula (R. -

QCD at Colliders

Particle Physics Dr Victoria Martin, Spring Semester 2012 Lecture 10: QCD at Colliders !Renormalisation in QCD !Asymptotic Freedom and Confinement in QCD !Lepton and Hadron Colliders !R = (e+e!!hadrons)/(e+e!"µ+µ!) !Measuring Jets !Fragmentation 1 From Last Lecture: QCD Summary • QCD: Quantum Chromodymanics is the quantum description of the strong force. • Gluons are the propagators of the QCD and carry colour and anti-colour, described by 8 Gell-Mann matrices, !. • For M calculate the appropriate colour factor from the ! matrices. 2 2 • The coupling constant #S is large at small q (confinement) and large at high q (asymptotic freedom). • Mesons and baryons are held together by QCD. • In high energy collisions, jets are the signatures of quark and gluon production. 2 Gluon self-Interactions and Confinement , Gluon self-interactions are believed to give e+ q rise to colour confinement , Qualitative picture: •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into Gluona flux tube self-Interactions” ande- Confinementq , + , What happens whenGluon try self-interactions to separate two are believedcoloured to giveobjects e.g. qqe q rise to colour confinement , Qualitativeq picture: q •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into a flux tube” e- q •Form a flux tube, What of happensinteracting when gluons try to separate of approximately two coloured constant objects e.g. qq energy density q q •Require infinite energy to separate coloured objects to infinity •Form a flux tube of interacting gluons of approximately constant •Coloured quarks and gluons are always confined within colourless states energy density •In this way QCD provides a plausible explanation of confinement – but not yet proven (although there has been recent progress with Lattice QCD) Prof. -

Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX Abstract

Technical Proposal for Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX arXiv:hep-ex/0505054v1 17 May 2005 J¨ulich, May 2005 2 Technical Proposal for PAX Frontmatter 3 Technical Proposal for Antiproton–Proton Scattering Experiments with Polarization ( Collaboration) PAX Abstract Polarized antiprotons, produced by spin filtering with an internal polarized gas target, provide access to a wealth of single– and double–spin observables, thereby opening a new window to physics uniquely accessible at the HESR. This includes a first measurement of the transversity distribution of the valence quarks in the proton, a test of the predicted opposite sign of the Sivers–function, related to the quark dis- tribution inside a transversely polarized nucleon, in Drell–Yan (DY) as compared to semi–inclusive DIS, and a first measurement of the moduli and the relative phase of the time–like electric and magnetic form factors GE,M of the proton. In polarized and unpolarized pp¯ elastic scattering, open questions like the contribution from the odd charge–symmetry Landshoff–mechanism at large t and spin–effects in the extraction | | of the forward scattering amplitude at low t can be addressed. The proposed de- | | tector consists of a large–angle apparatus optimized for the detection of DY electron pairs and a forward dipole spectrometer with excellent particle identification. The design and performance of the new components, required for the polarized antiproton program, are outlined. A low–energy Antiproton Polarizer Ring (APR) yields an antiproton beam polarization of Pp¯ = 0.3 to 0.4 after about two beam life times, which is of the order of 5–10 h. -

A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) JETS AND QCD: A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets and its Impact on QCD⋆ A.Ali1 and G.Kramer2 1 DESY, D-22603 Hamburg (Germany) 2 Universit¨at Hamburg, D-22761 Hamburg (Germany) Abstract. The observation of quark and gluon jets has played a crucial role in establishing Quantum Chromodynamics [QCD] as the theory of the strong interactions within the Standard Model of particle physics. The jets, narrowly collimated bundles of hadrons, reflect configurations of quarks and gluons at short distances. Thus, by analysing energy and angular distributions of the jets experimentally, the properties of the basic constituents of matter and the strong forces acting between them can be explored. In this review, which is primarily a description of the discovery of the quark and gluon jets and the impact of their obser- vation on Quantum Chromodynamics, we elaborate, in particular, the role of the gluons as the carriers of the strong force. Focusing on these basic points, jets in e+e− collisions will be in the foreground of the discussion and we will concentrate on the theory that was contempo- rary with the relevant experiments at the electron-positron colliders. In addition we will delineate the role of jets as tools for exploring other particle aspects in ep and pp/pp¯ collisions - quark and gluon densi- ties in protons, measurements of the QCD coupling, fundamental 2-2 quark/gluon scattering processes, but also the impact of jet decays of top quarks, and W ±, Z bosons on the electroweak sector. -

Probing 23% of the Universe at the Large Hadron Collider

Probing 23% of the Universe at the Large Hadron Collider Will Flanagan1 Advisor: Dr Teruki Kamon2 In close collaboration with Bhaskar Dutta2, Alfredo Gurrola2, Nikolay Kolev3, Tom Crockett2, Michael VanDyke2, and Abram Krislock2 1University of Colorado at Boulder, Cyclotron REU Program 2Texas A&M University 3University of Regina Introduction What is cosmologically significant about ‘focus Analysis With recent astronomical measurements, point’? We first decide which events we want to look for. χ~0 ~0 we know that 23% of the Universe is The 1is allowed to annihilate with itself since it is Since χ 1 is undetectable (otherwise it wouldn’t be ‘dark composed of dark matter, whose origin is its own antimatter particle. The χ~ 0 -χ~0 annihilation matter’!), we look for events with a 1 1 Red – Jet distribution unknown. Supersymmetry (SUSY), a leading cross section is typically too small (predicting a relic after MET cut large amount of missing transverse theory in particle physics, provides us with a cold dark χ~0 Z channel dark matter density that is too energy. Also, due to the nature of 1 u- matter candidate, the lightest supersymmetric particle Z0 large). The small µ of focus these decays (shown below) we also χ~0 (LSP). SUSY particles, including the LSP, can be 1 u point x require two energetic jets. 2 f 1 Ω ~0 ~h dx created at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. allows for a larger annihilation χ1 ∫ 0 σ v { ann g~ 2 energetic jets + 2 leptons We perform a systematic study to characterize the cross section for our dark 0.23 698 u- + MET 2 g~ SUSY signals in the "focus point" region, one of a few matter candidate by opening πα ~ u - σ annv = 2 u l cosmologically-allowed parameter regions in our SUSY up the ‘Z channel’ (pictured 321 8M χ~0 l+ 0.9 pb 2 ~+ model. -

E+ E~ ANNIHILATION Hinrich Meyer, Fachbereich Physik, Universitдt

- 155 - e+e~ ANNIHILATION Hinrich Meyer, Fachbereich Physik, Universität Wuppertal, Fed. Rep. Germany CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1. e+e~ STORAGE RINGS .1 Energy and Size .2 Luminosity .3 Energy range of one Ring .4 Energie resolution .5 Polarization 2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES .1 Storage Ring Detectors .2 Background .3 Luminosity Measurement .4 Radiative Corrections 3. QED-REACTIONS + . 1 e+e~ T T~ .2 e+e"+y+y~ . 3 e+e~ -»• e+e~ . 4 e+e_ •+y y 4. HADRON PRODUCTION IN e+e~ANNTHILATION .1 Total Cross Section .2 Average Event Properties .3 Two Jet Structure .4 Three Jet Structure .5 Gluon Properties - 156 - 5. SEARCH FOR NEW PARTICLES .1 Experimental Methods .2 Search for the sixth Flavor (t) .3 Properties of Q Q Resonances .4 New Leptons 6. YY ~ REACTIONS .1 General Properties .2 Resonance Production .3 £ for e,Y Scattering .4 Hard Scattering Processes .5 Photon Structure Function INTRODUCTION e+e storage rings have been proven to be an extremely fruitful techno• logical invention for particle physics. They were originally designed to provide stringent experimental tests of the theory of leptons and photons QED (Quantum-Electro-Dynamics). QED has passed these tests beautifully up to the highest energies (PETRA) so far achieved. The great successes of the e+e storage rings however are in the field of strong interaction physics. The list below gives a very brief overview of the historical development by quoting the highlights of physics results from e+e storage rings with the completion of storage rings of higher and higher energy (see Fig.1). YEAR -

Model of N¯ Annihilation in Experimental Searches for N¯ Transformations

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 99, 035002 (2019) Model of n¯ annihilation in experimental searches for n¯ transformations E. S. Golubeva,1 J. L. Barrow,2 and C. G. Ladd2 1Institute for Nuclear Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, Prospekt 60-letiya Oktyabrya 7a, Moscow, 117312, Russia 2University of Tennessee, Department of Physics, 401 Nielsen Physics Building, 1408 Circle Drive, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA (Received 24 July 2018; published 5 February 2019) Searches for baryon number violation, including searches for proton decay and neutron-antineutron transformation (n → n¯), are expected to play an important role in the evolution of our understanding of beyond standard model physics. The n → n¯ is a key prediction of certain popular theories of baryogenesis, and experiments such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment and the European Spallation Source plan to search for this process with bound- and free-neutron systems. Accurate simulation of this process in Monte Carlo will be important for the proper reconstruction and separation of these rare events from background. This article presents developments towards accurate simulation of the annihilation process for 12 use in a cold, free neutron beam for n → n¯ searches from nC¯ annihilation, as 6 C is the target of choice for the European Spallation Source’s NNBar Collaboration. Initial efforts are also made in this paper to 40 perform analogous studies for intranuclear transformation searches in 18Ar nuclei. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.99.035002 I. INTRODUCTION evacuated, magnetically shielded pipe of 76 m in length (corresponding to a flight time of ∼0.1 s), until being A. Background 12 allowed to hit a target of carbon (6 C) foil (with a thickness As early as 1967, A. -

Quark Annihilation and Lepton Formation Versus Pair Production and Neutrino Oscillation: the Fourth Generation of Leptons

Volume 2 PROGRESS IN PHYSICS April, 2011 Quark Annihilation and Lepton Formation versus Pair Production and Neutrino Oscillation: The Fourth Generation of Leptons T. X. Zhang Department of Physics, Alabama A & M University, Normal, Alabama E-mail: [email protected] The emergence or formation of leptons from particles composed of quarks is still re- mained very poorly understood. In this paper, we propose that leptons are formed by quark-antiquark annihilations. There are two types of quark-antiquark annihilations. Type-I quark-antiquark annihilation annihilates only color charges, which is an incom- plete annihilation and forms structureless and colorless but electrically charged leptons such as electron, muon, and tau particles. Type-II quark-antiquark annihilation an- nihilates both electric and color charges, which is a complete annihilation and forms structureless, colorless, and electrically neutral leptons such as electron, muon, and tau neutrinos. Analyzing these two types of annihilations between up and down quarks and antiquarks with an excited quantum state for each of them, we predict the fourth gener- ation of leptons named lambda particle and neutrino. On the contrary quark-antiquark annihilation, a lepton particle or neutrino, when it collides, can be disintegrated into a quark-antiquark pair. The disintegrated quark-antiquark pair, if it is excited and/or changed in flavor during the collision, will annihilate into another type of lepton par- ticle or neutrino. This quark-antiquark annihilation and pair production scenario pro- vides unique understanding for the formation of leptons, predicts the fourth generation of leptons, and explains the oscillation of neutrinos without hurting the standard model of particle physics. -

GLAST Science Glossary (PDF)

GLAST SCIENCE GLOSSARY Source: http://glast.sonoma.edu/science/gru/glossary.html Accretion — The process whereby a compact object such as a black hole or neutron star captures matter from a normal star or diffuse cloud. Active galactic nuclei (AGN) — The central region of some galaxies that appears as an extremely luminous point-like source of radiation. They are powered by supermassive black holes accreting nearby matter. Annihilation — The process whereby a particle and its antimatter counterpart interact, converting their mass into energy according to Einstein’s famous formula E = mc2. For example, the annihilation of an electron and positron results in the emission of two gamma-ray photons, each with an energy of 511 keV. Anticoincidence Detector — A system on a gamma-ray observatory that triggers when it detects an incoming charged particle (cosmic ray) so that the telescope will not mistake it for a gamma ray. Antimatter — A form of matter identical to atomic matter, but with the opposite electric charge. Arcminute — One-sixtieth of a degree on the sky. Like latitude and longitude on Earth's surface, we measure positions on the sky in angles. A semicircle that extends up across the sky from the eastern horizon to the western horizon is 180 degrees. One degree, therefore, is not a very big angle. An arcminute is an even smaller angle, 1/60 as large as a degree. The Moon and Sun are each about half a degree across, or about 30 arcminutes. If you take a sharp pencil and hold it at arm's length, then the point of that pencil as seen from your eye is about 3 arcminutes across.