1 Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Rosh Hashanah 5780/2019 Finding Our Place in the Story It Is Simchat Torah. the Two Boys Are Small E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2012

SHaloM HartMan Institute 2 012 ANNUAL REPORT תשעב - תשעג SHaloM HartMan Institute 2 012 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2 012 Developing Transformative Ideas: Kogod Research Center for Contemporary Jewish Thought 11 Research Teams 12 Center Fellows 14 iEngage: The Engaging Israel Project at the Shalom Hartman Institute 15 Beit Midrash Leadership Programs 19 Department of Publications 20 Annual Conferences 23 Public Study Opportunities 25 Strengthening Israeli-Jewish Identity: Center for Israeli-Jewish Identity 27 Be’eri Program for Jewish-Israeli Identity Education 28 Lev Aharon Program for Senior Army Officers 31 Model Orthodox High Schools 32 Hartman Conference for a Jewish-Democratic Israel 34 Improving North American Judaism Through Ideas: Shalom Hartman Institute of North America 37 Horizontal Approach: National Cohorts 39 Vertical Regional Presence: The City Model 43 SHI North America Methodology: Collaboration 46 The Hartman Community 47 Financials 2012 48 Board of Directors 50 ] From the President As I look back at 2012, I can do so only through the prism of my father’s illness and subsequent death in February 2013. The death of a founder can create many challenges for an institution. Given my father’s protracted illness, the Institute went through a leadership transition many years ago, and so the general state of the Institute is strong. Our programs in Israel and in North America are widely recognized as innovative and cutting-edge, and both reach and affect more people than ever before; the quality of our faculty and research and ideas instead of crisis and tragedy? are internationally recognized, and they Well, that’s iEngage. -

Gender in Jewish Studies

Gender in Jewish Studies Proceedings of the Sherman Conversations 2017 Volume 13 (2019) GUEST EDITOR Katja Stuerzenhofecker & Renate Smithuis ASSISTANT EDITOR Lawrence Rabone A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by © University of Manchester, UK. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, the University of Manchester, and the co-publisher, Gorgias Press LLC. All inquiries should be addressed to the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester (email: [email protected]). Co-Published by Gorgias Press LLC 954 River Road Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA Internet: www.gorgiaspress.com Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4632-4056-1 ISSN 1759-1953 This volume is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of paper for Printed Library Materials. Printed in the United States of America Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies is distributed electronically free of charge at www.melilahjournal.org Melilah is an interdisciplinary Open Access journal available in both electronic and book form concerned with Jewish law, history, literature, religion, culture and thought in the ancient, medieval and modern eras. Melilah: A Volume of Studies was founded by Edward Robertson and Meir Wallenstein, and published (in Hebrew) by Manchester University Press from 1944 to 1955. Five substantial volumes were produced before the series was discontinued; these are now available online. -

American Jews & Israel

American Jews & Israel Navigating Our Shared Destiny Featuring Natan Sharansky Sunday, May 17, 2020 10:00am - 5:00pm The J’s Staenberg Family Complex St. Louis premiere! jccstl.com/z3 About the Conference The Z3 Project, an initiative of the Oshman Family JCC in Palo Alto, CA, is committed to creating an ongoing, dynamic forum for opinions and ideas about Diaspora Jewry and Israel. The St. Louis Z3 conference will bring together high-level international and national thought leaders, scholars and journalists to educate and provide our community members an in-depth, nuanced understanding of pressing issues affecting Israel and the relationship between Israel and the American Jewish community. The conference will run as follows: • Opening Presentation • Breakout Session 1 (eight options) • Lunch and Israeli Organization Fair • Breakout Session 2 (same eight options repeated) • Conversation Cafe and Israeli Organization Fair • Closing Presentation $45 includes lunch Students 21 and under $18 Scholarship funds available In order to ensure breakout session and lunch choices, each person must register separately Contact: Diane Maier 314.442.3190, [email protected] Register online! Details at jccstl.com/z3 Opening Presentation - Avraham Infeld Avraham Infeld is the President Emeritus of Hillel – the Foundation for Jewish Campus life. Today, he serves as a consultant on Tikkun Olam to the Reut Institute and is a member of the Faculty of the Mandel Institute. In May 2012, Avraham was elected Chairman of the Board of the Hillels of Israel. In 1970, Avraham founded Melitz, a non-profit educational service institution that fosters Jewish identity. He also served as chairman of Arevim, founding chairman of the San Francisco Federation’s Amuta in Israel, and chairman of the Board of Israel Experience, Ltd. -

Catalog+Electronic+Reduced.Pdf

CONTENTS Dear Friends, Slavic Studies ……………..……..……… . 2 cademic Studies Press is pleased to present a wide selection of new titles for the scholar Jewish Studies ……………..……...……. 15 A and general reader alike. True to ASP’s mission, the core of our catalog consists of titles in Jewish and Slavic Studies. Highlights include Jewish City or Inferno of Russian Israel? by Linguistics …………………….…...…… 41 Victoria Khiterer, which explores the history of the Jewish community of Kiev from the tenth ASP Open ………………………….…… 42 century to the February 1917 revolution; Watersheds: Poetics and Politics of the Danube River, New in Paperback …………………..….. 43 edited by Marijeta Bozovic and Matthew D. Miller, which comprises multidisciplinary essays using the Danube as a conduit of multidirectional migration and cultural transfers and exchange Selected Backlist …...……………........... 45 and thus, a site of transcultural engagement and instantiation of a global present; and The Image Journals …………………………….…… 49 of Jews in Contemporary China edited by James Ross and Song Lihong, which examines the image of Jews from the contemporary perspective of ordinary Chinese citizens. Series ……………….……………........... 52 Inquires ...…………………….….….……59 We are also pleased to announce the founding of several new series, many of which extend Sales Representation & Distribution …… 60 beyond the fields of Jewish and Slavic Studies. Among these are “Iranian Studies,” edited by Sussan Siavoshi (Trinity University); “Ottoman and Turkish Studies,” edited by Hakan T. Index ……………………………............. 62 Karateke (University of Chicago); “Central Asian Studies,” edited by Timothy May (University of North Georgia); “Evolution, Cognition, and the Arts,” edited by Brian Boyd (University of Auckland); and “Studies in Lexical Science,” edited by Alain Polguère (Université de Lorraine). -

SHI Rabbanic Brochure Usletter.Indd

SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE Rabbinic Leadership Programs Hartman Rabbinic Leadership Programs Since its inception more than 35 years ago, the Shalom Hartman Institute has made the advancement of rabbinic leadership a core mission. Widely recognized as a leader in pluralistic, intensive, thoughtful, and challenging study, the Institute offers a variety of rabbinic programs universally respected for quality of faculty and depth of Torah study. Rabbis today fulfill many roles simultaneously — spiritual leader, community leader, counselor, teacher, administrator, fundraiser. With so many capacities to fill, rabbis often neglect their own ongoing intellectual and spiritual development and have limited opportunity for mutually beneficial interaction with rabbinic colleagues. Recognizing the crucial role that rabbis play and their need for support and reinvigoration, the Hartman Institute offers structured frameworks for ongoing rabbinic study, enrichment, and thought leadership training. Rabbis studying together in the spiritually and intellectually challenging Hartman rabbinic leadership programs enrich their textual knowledge, broaden the range of ideas they encounter, and deepen their relationship with Israel. Tasked with continually infusing their communities with new energy, Hartman rabbinic programs focus on helping participants to develop their own voices as intellectual and spiritual leaders in the pursuit of becoming ever-more significant agents of change in Jewish life. “ Learning with the team of scholars and thinkers that David Hartman z”l assembled at the Shalom Hartman Institute transformed my rabbinate by giving me direction and vision in Jewish thinking based on innovative interpretations of age-old sources in our tradition. Every teacher was an inspiration, each with their own unique style. The learning combined the intellectual rigor of an academic setting with the fulfilling bond with our tradition that yeshiva learning provides. -

Inside the Shalom Hartman Institute

INSIDE THE SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE The Shalom Hartman Institute (SHI) is a center of transformative thinking and teaching that addresses the major challenges facing the Jewish people and elevates the quality of Jewish life in Israel and around the world. At the forefront of sophisticated, idea-based Jewish education for community leaders and change agents, the Institute is committed to the significance of Jewish ideas, the power of applied scholarship, and the conviction that great teaching contributes to the growth and continual revitalization of the Jewish people. The Institute consists of three divisions: The Kogod Research Center for Contemporary Jewish Thought generates ideas and research on contemporary issues central to Jewish life in Israel and around the world. The Institute’s independent, multidenominational think tank, draws on thousands of years of Jewish intellectual thought to develop new ideas that shape and enrich modern Jewish life. The Center for Israeli-Jewish Identity creates educational models and infrastructure aimed at nurturing pluralistic Jewish identity among educators and senior Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officers. Introducing present and future Israeli change agents to a multifaceted approach to Judaism that is meaningful and relevant to their lives creates a ripple effect in the communities in which they operate. The Shalom Hartman Institute of North America partners with North American Jewish change agents—rabbis, lay leaders, scholars, educators, and professionals—to leverage unique models of pluralistic, -

Global Justice Fellowship 2017–2018 Fellows and Staff Bios

GLOBAL JUSTICE FELLOWSHIP 2017–2018 FELLOWS AND STAFF BIOS The AJWS Global Justice Fellowship is a selective program designed to inspire, educate and train key opinion leaders in the American Jewish community to become advocates in support of U.S. policies that will help improve the lives of people in the developing world. AJWS has launched the latest Global Justice Fellowship program, which will include leading rabbis from across the United States. The fellowship period is from October (2017) to April (2018) and includes travel to an AJWS country in Mesoamerica, during which participants will learn from grassroots activists working to overcome poverty and injustice. The travel experience will be preceded by innovative trainings that will prepare rabbis to galvanize their communities and networks to advance AJWS’s work. Fellows will also convene in Washington, D.C. to serve as key advocates to impact AJWS’s priority policy areas. The 14 fellows represent a broad array of backgrounds, communities, experiences and networks. RABBINIC FELLOWS LAURA ABRASLEY NOAH FARKAS Rabbi Laura J. Abrasley is a rabbi Rabbi Noah Farkas serves at Valley at Temple Shalom in Newton, Beth Shalom (VBS), the largest Massachusetts. She has served this congregation in California’s San congregation since July of 2015, Fernando Valley. He was ordained and is committed to inspiring and at the Jewish Theological Seminary implementing active, engaged in 2008, and before joining VBS, opportunities for connection, community, lifelong he served as the rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Jewish learning and tikkun olam—repairing the world— Biloxi, Mississippi, where he helped rebuild the Jewish among her congregants. -

HARTMAN VIDEO LECTURE SERIES Hartman Video Lecture Series

HARTMAN VIDEO LECTURE SERIES Hartman Video Lecture Series The Video Lecture Series enable rabbis to bring the scholarship and resources of the Hartman Institute into their congregations, fostering high-level adult education. Combining lectures from Institute faculty on video with in-person hevruta study facilitated by local rabbis, these series enable year-round learning on pressing issues facing the Jewish community. Each volume includes 8-10 video lectures on DVD or USB, student sourcebooks with primary texts, recommended background readings, and a leader’s guide with helpful lecture and text summaries and discussion questions. The Hartman Institute provides ongoing support for local faculty in the form of webinars and one-on-one consultation. The Video Lecture Series enhance the knowledge and engagement of lay leaders, expanding their ability to respond to key questions facing the Jewish people and contemporary society. Role of Rabbi/Educator The Video Lecture Series and accompanying curricular study materials are designed to be used by a local rabbi or educator with a group of lay leaders in a weekly or monthly study program. The rabbi/educator serves as the teacher, utilizing the materials and lectures as best suited for the local community. Participants prepare for the lecture by studying the texts and reading the supplementary materials, either in a separate class session or as the fi rst hour of a longer seminar. Hartman Video Lecture Series Catalogue Engaging Israel: Foundations for a New Relationship Going deeper than politics or advocacy, the first Engaging Israel series reframes the discussion about the enduring significance of the State of Israel for contemporary Jews worldwide. -

INSIDE the Eastside Is a Happening Place

INSIDE MJCC returns as Jewish community's living room – page 2 101-year-old Frieda Cohen to receive Nemer Award – page 2 July 21, 2021 / Av 12, 5781 Volume 56, Issue 16 From Ethiopia to Israel to international The eastside is a happening place art fame – page 3 BY DEBORAH MOON Jewish options are multiply- Song of Miriam honors ing on Portland’s eastside in volunteers – page 4 the Eastside Jewish Commons’ beautiful, airy new home con- Portlander to coach veniently located on Sandy Maccabiah masters' Boulevard. – page 5 “Our goal is to offer space to basketball the community at low cost … (to enable) lots of different fla- Shaarie Torah annual vors for Jewish life,” says EJC meeting – page 5 Board Chair Mia Birk. Congregation Shir Tik- New Faces at CSP vah, the leaseholder for the – page 6 13,000-square-foot space, and JFGP moved into a suite of four of- Young campers enjoy B’nai B’rith Camp’s first eastside day camp fices off the entry vestibule at July 12-16. The new Eastside Jewish Commons will be home for Michael Jeser 2420 NE Sandy Blvd. on May many community programs, including two more weeks of BB Day honored – page 6 1 and held its first full Shabbat Camp Eastside Aug. 2-6 and Aug. 9-13. service and activities June 26. Principal transition at In July, as COVID restrictions “The energy in the Com- July 6. “From giving tours Maimonides – page 7 lifted and the new executive di- mons this first week has been to interested community or- rector came on board, EJC and amazing,” says Cara Abrams, ganizations and individuals, its partners began presenting who began her position as to connecting with Jewish Kesser Israel unveils bigger activities. -

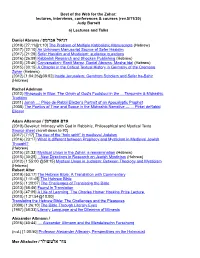

Best of the Web for the Zohar

Best of the Web for the Zohar: lectures, interviews, conferences & courses (rev.5/11/20) Judy Barrett a) Lectures and Talks דניאל אברמס / Daniel Abrams (2019) [27:11@1:10] The Problem of Multiple Kabbalistic Manuscripts (Hebrew) (2017) [22:10] An Unknown Manuscript Source of Sefer Hasidim (2017) [21:29] Sefer Hasidim and Mysticism: audience questions (2016) [26:09] Kabbalah Research and Shocken Publishing (Hebrew) (2015) [25:46] Conversation: Ronit Meroz, Daniel Abrams, Moshe Idel (Hebrew) (2015) [30:15] A Chapter in the Critical Textual History in Germany of the Cremona Zohar (Hebrew) (2012) [1:04:26@38:02] Inside Jerusalem: Gershom Scholem and Sefer ha-Bahir (Hebrew) Rachel Adelman (2012) Rhapsody in Blue: The Origin of God's Footstool in the ... Targumim & Midrashic Tradition (2011) Jonah ...: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer's Portrait of an Apocalyptic Prophet (2008) The Poetics of Time and Space in the Midrashic Narrative — ... Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer אדם אפטרמן / Adam Afterman (2019) Devekut: Intimacy with God in Rabbinic, Philosophical and Mystical Texts Source sheet (scroll down to #2) (2017) [7:17] The rise of the “holy spirit” in medieval Judaism (2016) [23:17] What is different between Prophecy and Mysticism in Medieval Jewish Thought? (Hebrew) (2015) [31:33] Mystical Union in the Zohar: a reexamination (Hebrew) (2015) [30:25] ...New Directions in Research on Jewish Mysticism (Hebrew) (2012) [1:55:00 @58:15] Mystical Union in Judaism: Between Theology and Mysticism (Hebrew) Robert Alter (2019) [53:17] The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (2018) [1:11:45] The Hebrew Bible (2015) [1:20:07] The Challenges of Translating the Bible (2013) [58:45] Found In Translation (2013) [47:09] A Life of Learning. -

The Honorable Michael R. Pompeo Secretary of State U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street NW Washington, D.C

The Honorable Michael R. Pompeo Secretary of State U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20250 August 22, 2019 Dear Mr. Secretary, As we mark the second-year anniversary of the continued campaign of genocide against the Rohingya people of Burma on August 25, we call on you to prioritize the pursuit of justice and accountability for the Rohingya people and all ethnic minorities in Burma. As 575 rabbis and Jewish clergy from 38 states across the U.S. and from many Jewish denominational backgrounds, we collectively serve tens of thousands of American Jews and represent this call-to-action from many more communities and congregations. As clergy, we have not—and will not—stay silent in the face of genocide. We know all too well, from our own Jewish history, what happens when the international community does not stand up unequivocally in defense of oppressed minorities subject to state-sanctioned hate, oppression and violence. The Department of State released a report in September 2018 documenting atrocities in Northern Rakhine State, which attests that the violence against the Rohingya people was “extreme, large- scaled, widespread” and “well-planned.” We were deeply disappointed that the report failed to legally determine that there were international crimes committed against the Rohingya people by the Burmese military. The horrifying atrocities outlined in the report—with the full weight and expertise of the Department of State behind it—surely must trigger meaningful U.S. response and actions. We call on you, Mr. Secretary, as you lead the Department, to defend the rights and dignity of the Rohingya people and other ethnic minorities. -

Shalom Hartman Institute Rethinking the Partnership Between Israel And

Shalom Hartman Institute Rethinking the Partnership Between Israel and World Jewry Rabbi Dr. Donniel Hartman Contents Copyright © 2008 Shalom Hartman Institute, Jerusalem, Israel hartman.org.il | [email protected] Israel at 60: Rethinking the Partnership Between Israel and World Jewry By Donniel Hartman "Next Year in Jerusalem;" "If I forget you Jerusalem;" "And to Jerusalem Your city may You return in compassion;" May our eyes behold Your return to Zion." For nearly 2,000 years these words gave expression to the Jewish people's longing for redemption and their dream to return to their homeland in Israel. With the rebirth of the State, its founders expected, and with good cause, that all Jews would move to Israel. This movement in the Zionist lexicon was called aliyah (literally: ascent), rising from an inferior existence in the Diaspora to begin a new life in Israel - a life of greater opportunities and broader horizons made possible by the newfound reality of Jewish statehood. In the eyes of the State's founders, Israel was to be not merely the center of Jewish life, but its exclusive location. The Zionist narrative did not leave any place for a vibrant and ongoing Jewish community living outside of Israel that would constitute a permanent and parallel center for Jewish life. In the Zionist narrative, within a few years of the rebirth of the State, Diaspora Jewish life, for all intents and purposes, was to come to an end. Sixty years on, it seems the founding fathers both under- and overestimated the potential of the fledgling Jewish state.