Cult of the Outlaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybrid Variations on a Documentary Theme

Hybrid variations on a documentary theme Robert Stam1 1 É professor transdisciplinar da Universidade de Nova York. Autor de diversos livros sobre cinema e literatura, cinema e estudos culturais, incluindo Brazilian cinema, Reflexivity in film and literature, Subversive pleasure, Tropical multiculturalism, Film theory: an introduction, Literature through film e François Truffaut and friends. Formado pela Universidade da Califórnia, Berkeley, também frequentou a Universidade de Paris III. Lecionou na Tunísia, na França e no Brasil (USP, UFF, UFMG) E-mail: [email protected] revista brasileira de estudos de cinema e audiovisual | julho-dezembro 2013 Resumo ano 2 número 4 Embora muitas vezes encarado como pólos opostos, o documentário e a ficção são, na verdade, teórica e praticamente entrelaçados, assim como a história e a ficção, também convencionalmente definidos como opostos, são simbioticamente ligados. O historiador Hayden White argumentou em seu livro Metahistory que a distinção mito/ história é arbitrária e uma invenção recente. No que diz respeito ao cinema, bem como à escrita, White apontou que pouco importa se o mundo que é transmitido para o leitor/espectador é concebido para ser real ou imaginário, a forma de dar sentido discursivo a ele através do tropos e da montagem do enredo é idêntica (WHITE, 1973). Neste artigo, examinaremos as maneiras que a hibridação entre documentário e ficção tem sido mobilizada como radical recurso estético. Palavras-chave Documentário, ficção, hibridização, sentido discursivo. Abstract Although often assumed to be polar opposites, documentary and fiction are in fact theoretically and practically intermeshed, just as history and fiction, also conventually seen as opposites, are symbiotically connected. -

PDF Download in a Lonely Place Pdf Free Download

IN A LONELY PLACE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy B. Hughes | 192 pages | 06 May 2010 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141192314 | English | London, United Kingdom In a Lonely Place PDF Book This is a crisp black-and-white film with an almost ruthless efficiency of style. But what of the real thing? Guy Beach Swan. Well, if that's not wrapping it up with a nice pink ribbon, I don't know what is; and, as I came closer and closer to the end of it I said, 'Well, today is the day and I have to be ready. February 11, Concert. Yet perhaps they all sensed that they were doing the best work of their careers -- a film could be based on those three people and that experience. Now it doesn't matter Power pop , alternative rock. Short Takes — Nov 18, Thanks to the Whitney museum, the floating garden made it onto the water for a week in That ideal of simmering rapport underlies their first exchanges of glance and gaze and repartee, cinematically framed by the courtyard of their Spanish-style apartment complex. He starts writing again. As befits a film about a screenwriter, the film is intriguingly self-aware. A tour de force laying open the mind and motives of a killer with extraordinary empathy. But what makes this a heartbreaking tragedy instead of a jaded satire is that, beneath its bruised pessimism, the film still clings to the hope that art and integrity and love can survive in the wasteland—a hope that dies slowly, agonizingly before our eyes. -

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground

Introduction Nicholas Ray and the Potential of Cinema Culture STEVEN RYBIN AND WILL SCHEIBEL THE DIRECTOR OF CLASSIC FILMS SUCH AS They Live by Night, In a Lonely Place, Johnny Guitar, Rebel Without a Cause, and Bigger Than Life, among others, Nicholas Ray was the “cause célèbre of the auteur theory,” as critic Andrew Sarris once put it (107).1 But unlike his senior colleagues in Hollywood such as Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks, he remained a director at the margins of the American studio system. So too has he remained at the margins of academic film scholarship. Many fine schol‑ arly works on Ray, of course, have been published, ranging from Geoff Andrew’s important auteur study The Films of Nicholas Ray: The Poet of Nightfall and Bernard Eisenschitz’s authoritative biography Nicholas Ray: An American Journey (both first published in English in 1991 and 1993, respectively) to books on individual films by Ray, such as Dana Polan’s 1993 monograph on In a Lonely Place and J. David Slocum’s 2005 col‑ lection of essays on Rebel Without a Cause. In 2011, the year of his centennial, the restoration of his final film,We Can’t Go Home Again, by his widow and collaborator Susan Ray, signaled renewed interest in the director, as did the publication of a new biography, Nicholas Ray: The Glorious Failure of an American Director, by Patrick McGilligan. Yet what Nicholas Ray’s films tell us about Classical Hollywood cinema, what it was and will continue to be, is far from certain. 1 © 2014 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel After all, what most powerfully characterizes Ray’s films is not only what they are—products both of Hollywood’s studio and genre systems—but also what they might be. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

King of Kings (Original Magazine Format)

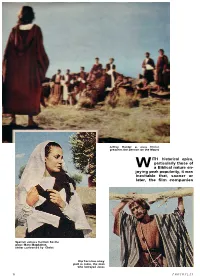

Jeffrey Hunter as Jesus Christ preaches the Sermon on the Mount ITH historical epics, W particularly those of a Biblical nature en- joying peak popularity, it was inevitable that, sooner or later, the film companies Spanish actress Carmen Sevilla plays Mary Magdalene, sinner converted by Christ Rip Torn has a key part as Judas, the man who betrayed Jesus 18 PHOTOPLAY Jeffrey Hunter was chosen to play Christ because of his compelling eyes would pick on the one all-em- bracing subject for a giant spectacular—the life of Christ. Samuel Bronston has now made the epic to end all epics with his King of Kings, produced for M-G-M. This production, (Continued overleaf) After a long search, Siobhan McKenna was cast as the Virgin Mary Viveca Lindfors portrays Claudia, the beautiful wife of Pontius Pilate Brigid Bazlen as the seductive Salome APRIL, 1961 19 The rebel, Barabbas (Harry Guardino) meets with Judas (Rip Torn) at the Sermon on the Mount (Continued from previous page) filmed in No matter how well the actors create Brigid Bazlen, from Chicago. Spain, has cost $8,000,000 — nearly the characters, it is the extras who create Brigid will not use the traditional seven £3,000,000. No expense has been spared the atmosphere which helps to bring the veils, but will dance using pure Oriental- to make it one of the most spectacular film to life. Examples of the authenticity African movements. and realistic pictures ever filmed. of their feelings occurred daily. There were many calls for stunt men The entire back lot of the Sevilla Studios While the scene depicting the sacrilegious during production. -

Rustin Military Collection

Richard Rustin Military Books Donated 3 October 2009 THE RUSTIN MILITARY COLLECTION The Rustin Military Collection consists of nearly a thousand military books and periodicals collected by Richard E. Rustin during his lifetime. His wife, Ginette Rustin, donated this collection from his estate to the Archive Center and Genealogy Department, Indian River County Main Library, in October 2009 – April 2010. Richard E. Rustin passed away July, 2008. His wife considered him a genius regarding military history. He was a brilliant writer, a former reporter, manager and assistant chief of the New York news bureau. He edited coverage at the heart of the Wall Street Journal’s financial and economic news operations. He served in the U. S. Navy as an officer from 1956 to 1959. The focus of his collection centered on World War I and World War II. The collection also includes books on the Revolutionary War, Civil War, Mexican War, Korean War, and Viet Nam War, among others. Regimental histories and books of detailed campaigns, military science, military equipment and biography predominate. The library is very fortunate to have such a magnificent research collection containing many rare, out of print and hard to find volumes. It should be of great interest to anyone exploring military history. To date, the complete collection has been processed and is available to the public in the Genealogy Department. Use the online catalog at http://www.irclibrary.org or browse the list below. Title Author Publ Date 106th Cavalry Group in Europe J. P. Himmer Co. 1945 10th Royal Hussars in the Second World War 1939-45 Dawnay, D., etc. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood

LH 19_1 FInal.qxp_Left History 19.1.qxd 2015-08-28 4:01 PM Page 57 Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood, Howard Fast, and the Demise of American Communism 1 Henry I. MacAdam, DeVry University Howard Fast is in town, helping them carpenter a six-million dollar production of his Spartacus . It is to be one of those super-duper Cecil deMille epics, all swollen up with cos - tumes and the genuine furniture, with the slave revolution far in the background and a love tri - angle bigger than the Empire State Building huge in the foreground . Michael Gold, 30 May 1959 —— Mike Gold has made savage comments about a book he clearly knows nothing about. Then he has announced, in advance of seeing it, precisely what sort of film will be made from the book. He knows nothing about the book, nothing about the film, nothing about the screenplay or who wrote it, nothing about [how] the book was purchased . Dalton Trumbo, 2 June 1959 Introduction Of the three tumultuous years (1958-1960) needed to transform Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus into the film of the same name, 1959 was the most problematic. From the start of production in late January until the end of all but re-shoots by late December, the project itself, the careers of its creators and financiers, and the studio that sponsored it were in jeopardy a half-dozen times. Blacklist Hollywood was a scary place to make a film based on a self-published novel by a “Commie author” (Fast), and a script by a “Commie screenwriter” (Trumbo). -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

The Inventory of the Albert Maltz Collection #150

The Inventory of the Albert Maltz Collection #150 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Albert Maltz Manuscripts Box 1 1.) This Gun for Hire (1942) by Albert Maltz & Wo R. Burnett Movie script, dated October 5, 19/41. Typescript, carbon, holograph corrections, 150p. a9x 1 2.) "Husband and Wife" Short story s·econd draft, typescript with holograph corrections, 44P• Final draft, typescript, heavily corrected, 33p. / C/·. \..c. Box 1 J.) The Underground Stream (1940) Novel 11 Final draft with ms. changes" Typescript, carbon, holograph corrections and additions, 373p. '"' Maltz, Albert - Addenda Box:-:- 2 Folder "Material from the magazine 1F.quality1 published in New York, 1939-4011 11 holograph articles Folder "Anonymous Writings and Ghost Writings" 6 articles: 5 holograph, 1 typed Folder "Miscellaneous Non-Fiction Pieces" 17 articles: 13 holograph, 4 typed. Folder "Public lectures and Addresses" 7 articles: 5 holograph, 1 mimeo, l typed Folder "Short Stories" Season of Celebration Notes and discards. Holograph. Sunday Morning .Q!l 25th Street First notes. Holograph. Happiest Man Q!l Earth Notes and discards, holograph. Typescript of one drafto Way Things Are Notes for first draft, holograph. Discards from first and second version, holograph. Notes for revision, holograph, Second draft typescript with holograph corrections. Final version type8cript, last 2 rages missing. (Each folder contains typed list by.Albert Maltz identifying articles and giving number of pages of each piece.) Mi.ltz, Albert Addenda, October., 1967 SCBEENPLAY .-- . THE BOBE . A. Second draft of the screenplay, typed script with holograph changes ·on ~bi~type~cent of the pages. :.~2S pages. · .· ::,;:~:: ·<·: i; l · ;' . • • ;.:• B. Third' (final) draf.t, mimeographed ·224 pages.