MTV Asia: Localizing the Global Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg Interactive Channels 5145 Tropicales 225 The Weather Channel 90 Interactive Dashboard 5146 Mexicana 2 City of Las Vegas Television 230 C-SPAN 92 Interactive Games 5147 Romances 3 NBC 231 C-SPAN2 4 Clark County Television 251 TLC Digital Music Channels PrismTM Complete 5 FOX 255 Travel Channel 5101 Hit List TM 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 265 National Geographic Channel 5102 Hip Hop & R&B Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 7 Universal Sports 271 History 5103 Mix Tape 132 American Life 8 CBS 303 Disney Channel 5104 Dance/Electronica 149 G4 9 LATV 314 Nickelodeon 5105 Rap (uncensored) 153 Chiller 10 PBS 326 Cartoon Network 5106 Hip Hop Classics 157 TV One 11 V-Me 327 Boomerang 5107 Throwback Jamz 161 Sleuth 12 PBS Create 337 Sprout 5108 R&B Classics 173 GSN 13 ABC 361 Lifetime Television 5109 R&B Soul 188 BBC America 14 Mexicanal 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5110 Gospel 189 Current TV 15 Univision 364 Lifetime Real Women 5111 Reggae 195 ION 17 Telefutura 368 Oxygen 5112 Classic Rock 253 Animal Planet 18 QVC 420 QVC 5113 Retro Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 19 Home Shopping Network 422 Home Shopping Network 5114 Rock 258 Science Channel 21 My Network TV 424 ShopNBC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 25 Vegas TV 428 Jewelry Television 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 27 ESPN 451 HGTV 5117 Classic Alternative 272 Biography 28 ESPN2 453 Food Network 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 274 History International 33 CW 503 MTV 5120 Soft Rock 305 Disney XD 39 Telemundo 519 VH1 5121 Pop Hits 315 Nick Too 109 TNT 526 CMT 5122 90s 316 Nicktoons 113 TBS 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5123 80s 320 Nick Jr. -

1:00 PM Jim West Regional Transit Center Board Room

NORTH CENTRAL REGIONAL TRANSIT DISTRICT BOARD MEETING AGENDA March 4, 2016 9:00 AM - 1:00 PM Jim West Regional Transit Center Board Room CALL TO ORDER: 1. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 2. MOMENT OF SILENCE 3. ROLL CALL 4. INTRODUCTIONS 5. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 6. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – February 5, 2016 7. PUBLIC COMMENTS PRESENTATION ITEMS: A. Above and Beyond Quarterly Award Sponsor: Daniel Barrone, Chairman and Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director ACTION ITEMS: B. Discussion and Consideration of Resolution 2016-08 Adopting a Veterans “Fare Free” on Fare Service Routes Sponsor: Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director and Troy Bingham, Finance Director. Attachment. C. Discussion and Consideration of Resolution No. 2016-09 Adopting the NCRTD’s Title VI Program Sponsor: Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director, Daria Veprek, Human Resources Director and Stacey McGuire, Planning, Projects and Grants Manager. Attachment. D. Discussion and Consideration of Award of Contract – On-Call Engineering Services Sponsor: Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director and Troy Bingham, Finance Director. Attachments will be disbursed prior to the meeting. E. Discussion and Consideration of Acquisition of Intelligent Transit System Equipment from Avail for Taos Chili Line Fleet Sponsor: Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director and Troy Bingham, Finance Director Attachments will be disbursed prior to the meeting. F. Discussion and Consideration of Resolution 2016-10 Authorizing NCRTD Staff to apply for Federal Funding through the FFY2016 Inclusive Planning Impact Grant Program (to Improve Transit Options for the Elderly and/or Disabled) Sponsor: Anthony J. Mortillaro, Executive Director and Stacey McGuire, Planning, Projects and Grants Manager. Attachment G. Discussion and Consideration for Board Direction Related to Weekend Special Event Service as a Component of the La Cienega 6-Month Pilot Route Sponsor: Anthony J. -

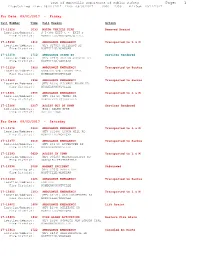

Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 09/01/2017 Thru: 09/30/2017 0000 - 2359 Printed: 10/11/2017

Town of Montville Department of Public Safety Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 09/01/2017 Thru: 09/30/2017 0000 - 2359 Printed: 10/11/2017 For Date: 09/01/2017 - Friday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 17-15324 1033 MOTOR VEHICLE FIRE Removed Hazard Location/Address: S I-395 EXIT 6 - EXIT 5 Fire District: MONTVILLE/MOHEGAN/Q-HILL 17-15336 1412 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to L & M Location/Address: [MTV S2752] KITEMAUG RD Fire District: MONTVILLE/MOHEGAN 17-15358 1712 AMBULANCE STAND BY Services Rendered Location/Address: [MTV B454] OLD COLCHESTER RD Fire District: MONTVILLE/OAKDALE 17-15359 1900 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to Backus Location/Address: NORWICH NEW LONDON TPKE Fire District: MOHEGAN/MONTVILLE 17-15360 1934 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to Backus Location/Address: [MTV B279] RICHARD BROWN DR Fire District: MOHEGAN/MONTVILLE 17-15361 1955 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to L & M Location/Address: [MTV S6272] TEXAS DR Fire District: OAKDALE/CHESTERFIELD 17-15366 2207 ASSIST OUT OF TOWN Services Rendered Location/Address: [BOZ] SALEM TPKE Fire District: OUT OF TOWN For Date: 09/02/2017 - Saturday 17-15376 0324 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to L & M Location/Address: [MTV S3244] LYNCH HILL RD Fire District: MONTVILLE/MOHEGAN 17-15377 0616 AMBULANCE EMERGENCY Transported to Backus Location/Address: [MTV S5278] RIVERVIEW RD Fire District: MOHEGAN/MONTVILLE 17-15393 0829 ASSIST IN TOWN Transported to L & M Location/Address: [MTV S3525] MASSACHUSETTS RD Fire District: OAKDALE/CHESTERFIELD 17-15394 1026 HAZMAT INCIDENT Unfounded -

MTV's Most Popular Veejay Doesn't Intend to Spend the Rest of His Life About Th~T

.)'...4. ':' ~ •• 1.01 .... ' 1 .. , . ....',J.iu,. " .. ~ ' t..... l hr n lOtI< 'O!!T, 3Ui<4CAt . J1d4UARi 23 . 200(} n -_ •• NEW YORK POST SUNOAY . JANUA~Y 23 . 2000 ~ • • •1 • i ;s ..... " l1tsu)iYlI~ ' ~ -------------------------------------- MTV's most popular veejay doesn't intend to spend the rest of his life about th~t : . -.- -:. :.-....-;~ . ..~.id!!, _1M ~cripl'" . introducing Britney Spears videos. He has plans beyond "Total Request Live" . t..opiee-,-a ..... ant nLe . andlor dirtrt.........: f1iat "" ould and music-video TV. He's talking about branching out mogul-style into I- be the audience," I ;·• .. • end, nnly'fI been sitcoms and movies. And a lot of important people are listening. on JIIIitcom and ..... ith MTV pro- ducer and roomie Juon Ryan (Along with «orne other friends I They plan to By MICHAEl GllTZ film a short lo ter this year in New York and then take EE:-JAGE ~irl,. ....· Rnt it from there. Car!'on Daly. Tht'y Oaly'a st.udy riJO(, loch • T.queal over hi" every like the re.-ult nf a ~II\'V)' move while c8mpin~ outside cnee r plan. but d un't MlVs Time Square studio believe it. where Only ho!'! ' s "Total "I'm an idiot: in )<: i!" t1" Onh' Rcqucllt Live" - MlVs .. , don'l kno ..... nn." pl<iycn:; in anernoon countdown !'!ho ..... '., the bu.sint'I'II. J !l; hnulct prnh· that's become thl.' network's ably buy a Who'" ImportAnt most pnpulur ~eri('s . A1manac bt'for(' I sav :otI nll'· Record compnnil.'s want thing .stupId in fron't u( th(' Daly. -

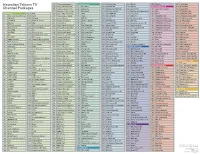

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Packages

Hawaiian Telcom TV 604 Stingray Everything 80’s ADVANTAGE PLUS 1003 FOX-KHON HD 1208 BET HD 1712 Pets.TV 525 Thriller Max 605 Stingray Nothin but 90’s 21 NHK World 1004 ABC-KITV HD 1209 VH1 HD MOVIE VARIETY PACK 526 Movie MAX Channel Packages 606 Stingray Jukebox Oldies 22 Arirang TV 1005 KFVE (Independent) HD 1226 Lifetime HD 380 Sony Movie Channel 527 Latino MAX 607 Stingray Groove (Disco & Funk) 23 KBS World 1006 KBFD (Korean) HD 1227 Lifetime Movie Network HD 381 EPIX 1401 STARZ (East) HD ADVANTAGE 125 TNT 608 Stingray Maximum Party 24 TVK1 1007 CBS-KGMB HD 1229 Oxygen HD 382 EPIX 2 1402 STARZ (West) HD 1 Video On Demand Previews 126 truTV 609 Stingray Dance Clubbin’ 25 TVK2 1008 NBC-KHNL HD 1230 WE tv HD 387 STARZ ENCORE 1405 STARZ Kids & Family HD 2 CW-KHON 127 TV Land 610 Stingray The Spa 28 NTD TV 1009 QVC HD 1231 Food Network HD 388 STARZ ENCORE Black 1407 STARZ Comedy HD 3 FOX-KHON 128 Hallmark Channel 611 Stingray Classic Rock 29 MYX TV (Filipino) 1011 PBS-KHET HD 1232 HGTV HD 389 STARZ ENCORE Suspense 1409 STARZ Edge HD 4 ABC-KITV 129 A&E 612 Stingray Rock 30 Mnet 1017 Jewelry TV HD 1233 Destination America HD 390 STARZ ENCORE Family 1451 Showtime HD 5 KFVE (Independent) 130 National Geographic Channel 613 Stingray Alt Rock Classics 31 PAC-12 National 1027 KPXO ION HD 1234 DIY Network HD 391 STARZ ENCORE Action 1452 Showtime East HD 6 KBFD (Korean) 131 Discovery Channel 614 Stingray Rock Alternative 32 PAC-12 Arizona 1069 TWC SportsNet HD 1235 Cooking Channel HD 392 STARZ ENCORE Classic 1453 Showtime - SHO2 HD 7 CBS-KGMB 132 -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

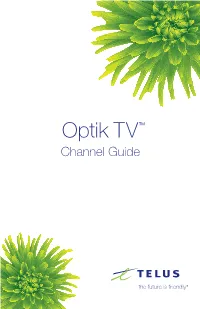

Navigate Your Optik TVTM Channels with Ease

TM Optik TV Channel Guide Navigate your Optik TVTM channels with ease. Optik TV channels are grouped by categories beginning at easy to remember numbers. 100 Major networks 900 Sports & PPV 200 Timeshift 1000 Premium sports 300 Entertainment 2000 French 400 Movies & series 2300 Multicultural 500 Comedy & Music 5000 Adult 600 Kids & family 7000 Radio 700 Learning 7500 Stingray music 800 News 9000 Corresponding SD channels 3 easy ways to find your favourite channels: n Enter the category start channel number on your remote and scroll through the guide n Use the on your remote and enter the program or channel name n Use the search function in your Optik Smart Remote App. Essentials Refer to Time Choice for channel numbers. Bold font indicates high definition channels. Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver / Kelowna / Prince Dawson Victoria / Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 AMI-audio AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West) ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 APTN HD APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 BC Legislative TV BCLEG — — — — -

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

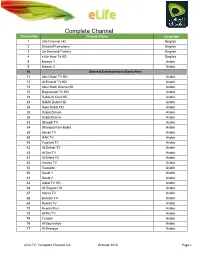

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

BEFORE the DIRECTOR 0? COMMERCE and CONSUMER

C) BEFORE ThE DIRECTOR 0? COMMERCE AND CONSUMER AFFAIRS OF TUE STATE OF UAWAU In the Matter of the Application of WAIANAE TELEVISION & ) DOCKET NO. 12-84-01 COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION) ORDER NO. 107 ) For Transfer of the CATV Permits and Assets of TV Systems, Inc. DECISION AND ORDER On June 26, 1984, the duly appointed Hearings Officer submitted his Recommended Decision to the Director and the Recommended Decision was served on aU parties. On June 28, 1984, Waianae Television and Communications Corporation (“Oceanic”) submitted a letter requesting the Director to amend one of the conditions proposed in the Recommended Decision. Having reviewed the Recommended Decision, Oceanic’s June 28, 1984 submission, and other pertinent information in this case, the Director hereby adopts the Hearings Officer’s Recommended Decision (attached hereto as Attachment 1) as the final Decision in this proceeding, with the following clarifications and exceptions: 1. City and County of Honolulu. The purposes cited in the Recommended Decision for the proposed two—way cable drops to Honolulu Hale and the Honolulu Municipal Building were suggested by the Office of Human Resources in testimony submitted in this proceeding. The suggested programming is not intended to be required by this Decision and Order. Under the provisions hereof Oceanic is to work with the City and County of Honolulu to provide the basic physical cable connections to the Oahu Civil Defense Agency in the Honolulu Municipal Building and to Honolulu Hale which will allow the various components of Honolulu’s municipal government to receive or transmit the programming of their choice when they are ready to do so. -

Nine Constructions of the Crossover Between Western Art and Popular Musics (1995-2005)

Subject to Change: Nine constructions of the crossover between Western art and popular musics (1995-2005) Aliese Millington Thesis submitted to fulfil the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide October 2007 Contents List of Tables…..…………………………………………………………....iii List of Plates…………………………………………………………….......iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………...v Declaration………………………………………………………………….vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………...vii Chapter One Introduction…………………………………..…..1 Chapter Two Crossover as a marketing strategy…………....…43 Chapter Three Crossover: constructing individuality?.................69 Chapter Four Shortcuts and signposts: crossover and media themes..…………………...90 Chapter Five Evoking associations: crossover, prestige and credibility………….….110 Chapter Six Attracting audiences: alternate constructions of crossover……..……..135 Chapter Seven Death and homogenization: crossover and two musical debates……..……...160 Chapter Eight Conclusions…………………..………………...180 Appendices Appendix A The historical context of crossover ….………...186 Appendix B Biographies of the four primary artists..…….....198 References …...……...………………………………………………...…..223 ii List of Tables Table 1 Nine constructions of crossover…………………………...16-17 iii List of Plates 1 Promotional photograph of bond reproduced from (Shine 2002)……………………………………….19 2 Promotional photograph of FourPlay String Quartet reproduced from (FourPlay 2007g)………………………………….20 3 Promotional -

Quebrando Recordes E Paradigmas: Como Superar As Expectativas De Uma Indústria Em Declínio – O Caso Taylor Swift

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ALINE LOPES DA SILVA CANDÉO QUEBRANDO RECORDES E PARADIGMAS: COMO SUPERAR AS EXPECTATIVAS DE UMA INDÚSTRIA EM DECLÍNIO – O CASO TAYLOR SWIFT TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO DE CURSO Curitiba 2015 ALINE LOPES DA SILVA CANDÉO QUEBRANDO RECORDES E PARADIGMAS: COMO SUPERAR AS EXPECTATIVAS DE UMA INDÚSTRIA EM DECLÍNIO – O CASO TAYLOR SWIFT Trabalho apresentado como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação Social com ênfase em Publicidade e Propaganda no curso de graduação em Comunicação Social – Publicidade e Propaganda, Setor de Artes, Comunicação e Design da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientador: Prof. Aryovaldo de Castro Azevedo Junior CURITIBA 2015 AGRADECIMENTOS À minha família, pela compreensão e paciência que tiveram durante o período em que levei para concluir este trabalho. Aos meus amigos, que me apoiaram e serviram de cobaias quando precisei que alguém fizesse uma leitura atrás de erros e que fornecessem sugestões. Ao meu orientador, Prof. Ary Azevedo, pelas dicas e conselhos que auxiliaram no norteamento do trabalho. RESUMO A indústria fonográfica passa por dificuldades. Seu período áureo foi nos anos 2000, mas a partir do momento que a internet se popularizou, as vendas de álbuns começaram a cair graças ao crescimento da pirataria. Agora, a indústria fonográfica corre para se adaptar ao mercado. Serviços de assinatura estão no meio da discussão sobre o futuro: Agradam os consumidores, com opções de conteúdo gratuito e pago, mas também causam divergência entre artistas, produtores, compositores e executivos que afirmam que os termos dos acordos ainda não são ideais para manter a indústria em equilíbrio. Este trabalho se propõe a analisar o caso de uma exceção da indústria: ao vender mais de um milhão de cópias na semana de lançamento dos seus três últimos álbuns, Taylor Swift estabeleceu uma marca sem precedentes. -

El Videoclip Como Paradigma De La Música Contemporánea, De 1970 a 2015

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y PUBLICIDAD I TESIS DOCTORAL El videoclip como paradigma de la música contemporánea, de 1970 a 2015 MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTORA PRESENTADA POR Lara García Soto DIRECTOR Francisco Reyes Sánchez Madrid, 2017 © Lara García Soto, 2016 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de CC. de la Información Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad I El videoclip como paradigma de la música contemporánea, de 1970 a 2015 Tesis doctoral presentada por: Lara García Soto. Tesis doctoral dirigida por: Francisco Reyes Sánchez. Madrid, 2015 El ejemplo, la fuerza y el esfuerzo, mis padres. La paciencia y apoyo, Adrián. La música, baile y mi inspiración, Michael Jackson. Gracias. ÍNDICE 1. Introducción y Objeto de estudio……………………………………1 2. Objetivos……………………………………………………………….6 3. Metodología………………………………………............................10 4. Orígenes……………………………………………………………….13 4.1. Cine sonoro y experiencias artísticas………………………13 4.2. Cine Musical…………………………………………………..18 4.3. Soundies y Scopitones……………………………………….25 4.4. La llegada de las películas rock, grabaciones de conciertos. Décadas de los 50 y 60……………………………………………29 4.5. El videoarte……………………………….............................38 4.6. La televisión y los programas musicales………………......41 4.6.1. La MTV………………………………………………...........48 4.6.2. Programas musicales en España………………………...57 4.6.3. Los canales temáticos de música y videoclips………….65 5. Historia de la música y relación con los videoclips……………….68 5.1. Los años 70…………………………………………………..69 5.2. Los años 80…………………………………………………..76 5.2.1. La televisión y los videoclips. Desarrollo del rap…..80 5.2.2. El primer muro. El PMRC…………………………….86 5.2.3. Continúa la evolución: música, tecnología y moda..89 5.2.4.