Māka'ika'i Ke Kōlea Travel Writing And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Hawaiian Newspapers

TRANSLATION IN THE CULTURE WAR FOR HAWAII The Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Hawaiian Newspapers ALYSSA HUGHES THIS ARTICLE DISCUSSES THE MOTIVATIONS BEHIND THE TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS IN TWO COMPETING N I N ET E E N T H-C E N T U R Y H A W A I I A N - LA N G U AG E NEWSPAPERS: KA HOKU PAKIPIKA AND KA NUPEPA KUOKOA. TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS SERVE AS AN EPICENTER OF CULTURAL CONFLICT IN THE WAR FOR SOCIETAL AND POLITICAL DOMINANCE OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS ON THE EVE OF THEIR ANNEXATION TO THE UNITED STATES. FURTHERMORE, THE ROLE OF TRANSLA- TION ITSELF IN THE FORMATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITIES IS DISCUSSED, FOCUSING ON THE ROLE OF THE TRANSLATIONS OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS IN THE WAR FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY IN N I N ET E E N T H - C E N T U R Y HAWAII. INTRODUCTION: SHAHRAZAD'S TALE various translations of the Arabic tales in Hawaiian-lan- ARRIVES IN THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS guage publications are more than simply another example of The Arabian Nights' dual nature—the tales' ability to On April 24, 1862, the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka exist in oral, printed and illustrated forms in societies so Hoku Pakipika published the story of Samesala Naeha, far-removed from that of their inception.111 In the case of "Moolelo no Samesala Naeha! O ka Moolelo keia o ka Mea The Arabian Nights in Hawaii, the tales act as a reflection of nana i haku i na Kaao Arabia" ("The Arabian Tale of colonial Hawaii mediated through language.lv Samesala Naeha"), a translation of the frame tale of The Arabian Nights. -

Joyce Pualani Warren

DOI 10.17953/aicrj.43.2.warren Reading Bodies, Writing Blackness: Anti-/Blackness and Nineteenth- Century Kanaka Maoli Literary Nationalism Joyce Pualani Warren June 5, 1850, journal entry written by fifteen-year-old Hawaiian Prince Alexander A Liholiho, the future King Kamehameha IV, details his experience of anti-Black discrimination on a train in Washington, DC. The conductor “told [him] to get out of the carriage rather unceremoniously,” because of his skin color, “saying that [he] was in the wrong carriage.”1 For Alexander Liholiho, a law school student as well as the future monarch, this diplomatic tour of the United States and Europe was an opportunity to interact with foreign heads of state. Although the conductor deferred to the prince after someone whispered into the official’s ear at a critical moment in the argument, Alexander Liholiho surmised in his entry, “he had taken me for somebodys servant [sic], just because I had a darker skin than he had. Confounded fool.”2 During a soiree at the White House only days earlier President Zachary Taylor and Vice President Millard Fillmore had treated him as an equal; now a train conductor cruelly abused him as a “servant” in need of correction. Perhaps ironically, the young prince had found the president’s “plain citizens dress” [sic] lacking in comparison to his own “belted & cocked” attire, yet none of the outward markers of his royalty registered with the conductor.3 Instead, the conductor misreads Alexander Liholiho’s body based on his racist assumption that a Black body, or a body approximating one, could occupy no other narrative than the one inscribed Joyce Pualani Warren is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. -

UNIVERSITY of HAWAII at MANOA LIBRARY Robert F. Walden

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA LIBRARY Robert F. Walden Collection (1936-1991) Finding Aid: Container and Folder Listing Inventory of Photographs Prepared by Bronwen Solyom Accession number: W1999:001 Archives & Manuscripts Department University of Hawaii at Manoa Library Honolulu, Hawaii July 2004, revised March 2006 © 2006 University of Hawaii Robert F. Walden Collection Contents Inventory of Photographs • Pearl Harbor Navy Yard (PHNY) 1941-1945…………………………………… 1 • Ships burning and damaged after Pearl Harbor attack ……………………… 1 • Ship salvage and repair ……………………………………………………… 2 o Divers ………………………………………………………………... 2 o USS Arizona ………………………………………………………… 3 o USS California ………………………………………………………. 5 o USS Cassin and USS Downes ………………………………………. 7 o USS Nevada …………………………………………………………. 8 o USS Oglala …………………………………………………….…….. 9 o USS Oklahoma ……………………………………………………... 12 o USS West Virginia ………………………………………………… 13 o USS Maryland ……………………………………………………… 20 • Ship repair and maintenance ……………………………………………….. 23 • Civilian workers in Yard shops…………………………………………….. 25 • Supply Department activities ………………………………………………. 27 • Scrap materials stockpiled at Berth 23 ……………………………………... 28 • Officers and senior civilian management…………………………………... 29 • Visiting dignitaries and special events ……………………………………... 30 • Return of the wounded, departure of troops………………………………... 34 • Civilian Housing Area III (CHAIII) 1942-1946 ……………………………….. 36 • Development and facilities…………………………………………………. 36 • Officers……………………………………………………………………... 46 • Special events………………………………………………………………. -

Pepeluali 2018 | Buke 35, Helu 2

Pepeluali 2018 | Buke 35, Helu 2 ‘O Faith Kaihopo¯lanihiwahiwa Hi‘ilei‘ilikeaopumehana De Ramos kekahi moho lanakila ma ‘Aha Aloha ‘O¯lelo 2018. - Ki‘i: Bryson Ho/‘O¯iwi TV THE LIVING WATER OF OHA www.oha.org/kwo $REAMINGOF THEFUTURE Hāloalaunuiakea Early Learning Center is a place where keiki love to go to school. It‘s also a safe place where staff feel good about helping their students to learn and prepare for a bright future. The center is run by Native Hawaiian U‘ilani Corr-Yorkman. U‘ilani wasn‘t always a business owner. She actually taught at DOE for 8 years. A Mālama Loan from OHA helped make her dream of owning her own preschool a reality. The low-interest loan allowed U‘ilani to buy fencing for the property, playground equipment, furniture, books…everything needed to open the doors of her business. U‘ilani and her staff serve the community in ‘Ele‘ele, Kaua‘i, and have become so popular that they have a waiting list. OHA is proud to support Native Hawaiian entrepreneurs in the pursuit of their business dreams. OHA‘s staff provide Native Hawaiian borrowers with personalized support and provide technical assistance to encourage the growth of Native Hawaiian businesses. Experience the OHA Loans difference. Call (808) 594-1924 or visit www.oha.org/ loans to learn how a loan from OHA can help grow your business. -A LAMALOAN CANMAKEYOURDREAMSCOMETRUE (808) 594-1924 www.oha.org/loans follow us: /oha_hawaii | /oha_hawaii | fan us: /officeofhawaiianaffairs | watch us: /OHAHawaii pepeluali 2018 3 ‘o¯lElo A kA lunA ho‘okElE MessAge frOM tHe CeO ‘o¯ lelo haWai‘i empoWers our la¯ hui Aloha mai ka¯kou, tongue to thrive, it should be used in as many spaces as possible, including while seeking justice in a Maui courtroom. -

Final Burial Treatment Plan for SIHP #50-10-28-13387, -26831 & -26836

Final Burial Treatment Plan for SIHP #50-10-28-13387, -26831 & -26836, Ane Keohokālole Highway Project, Keahuolū Ahupua‘a, North Kona District, Island of Hawai‘i TMK [3] 7-4-020: 010 por.; [3] 7-4-020: 022 por. Prepared for Belt Collins Hawai‘i Ltd. Prepared by Matt McDermott, M.A. and Jon Tulchin, B.A. Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc. Kailua, Hawai‘i (Job Code: KEALAKEHE 2) November 2009 O‘ahu Office Maui Office P.O. Box 1114 16 S. Market Street, Suite 2N Kailua, Hawai‘i 96734 Wailuku, Hawai‘i 96793 www.culturalsurveys.com Ph.: (808) 262-9972 Ph: (808) 242-9882 Fax: (808) 262-4950 Fax: (808) 244-1994 Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: KEALAKEHE 2 Management Summary Management Summary Reference Burial Treatment Plan for SIHP # 50-10-28-13387, -26831 & -26836, Ane Keohokālole Highway Project, Keahuolū Ahupua‘a, North Kona District, Island of Hawai‘i, TMK [3] 7-4-020: 010 por.; [3] 7-4-020: 022 por. (McDermott & Tulchin 2009) Date November 2009 Project Hawaii State Department of Transportation #: ARR - 1880 Number (s) Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Inc. (CSH) Job Code: KEALAKEHE 2 Agencies State of Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources / State Historic Preservation Division (DLNR / SHPD); County of Hawaii; Hawaii State Department of Transportation; Hawaii Island Burial Council (HIBC); Federal Highways Administration (FHWA) Area of The Ane Keohokālole Highway Project’s area of potential effect (APE) is Potential approximately defined as a 150- to 400-ft wide corridor oriented in a roughly Effect (APE) north-south direction extending about 3.0 miles from Hina Lani Street toward and Survey Palani Road, with an approximately 100-ft wide corridor oriented in a Acreage roughly east-west direction about 1,700 feet between the intersection of Palani Road/Henry Street to the intersection of Palani Road/Queen Ka‘ahumanu Highway (Figures 1-3). -

Community Guide to Hawai'i Land Conservation

Community Guide to Hawaiʻi Land Conservation “He aliʻi ka ʻāina; he kauwā ke kanaka.” “The land is a chief; man is its servant.” Mary Kawena Pukui, ʻŌlelo Noʻeau. According to Hawaiian historian Mary Kawena Pukui, “Land has no need for man, but man needs the land and works it for a livelihood.” Introduction / Preface Community members often ask Hawaiian Islands Land Trust, The Trust for Public Land’s Hawaiʻi Program, and other land trusts how they can work with land trusts to save particular lands of natural and cultural significance. This guide is intended to help those community members, and applies to land that: 1) is privately- owned, 2) has significant natural, cultural, or agricultural resources, and 3) is threatened with uses that would harm the resources, such as subdivision and development. Protecting a threatened special place can seem daunting or even impossible. Knowing who to call, what to research, and how to ask for assistance can be confusing. The Trust for Public Land and Hawaiian Islands Land Trust share this guide to clarify the voluntary land conservation process and empower communities across Hawaiʻi in protecting privately owned and threatened lands with cultural, agricultural, and/or ecolog- ical significance. Voluntary land conservation – buying land for public agencies or community organizations or restricting land uses on private property with the cooperation of the landowner — has resolved heated land disputes and created win-win-win solutions that benefit private landowners, our environment, community, and future gen- erations. Where land use is contentious, the process of collaboratively working toward the land’s protection often begins a healing process that can build community resiliency and connections. -

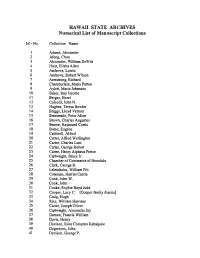

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Hawaiiansongcontestindex.Pdf

Hawaiian Song Composing Contest First annual, 1950-Twenty-eight annual, 1977 Volume I: List ofsong winner by year Index by song title Index by composer ' J~ I1- ~ 1950 ;#"~ ~ e-...,..,<; 7 ~ Ie ~1Ia..ru-' 'i ~rr- s« "p~ 1\~~" &., ~ Itt~ .scc "n-' ~·x;".h{'J,~~<Ir'_i~' 'It!- h~~"'J~~/!.L~' 1/.,1(.-1." "u.... ~() KA.c<" ~ ~rr-" . " ia-P/<4 ~ •~ 7ft s: ,4~' j ' &~~ ....J.. ljQi;l~~~~ /~ h~' f'...t",,, ,,~~ ~ ~~/kU~&;",~~,j~ he «~!t~"~~.~k~ : 9tL «fI,;;;,i..." b.; f'11./ »: ~J..,;, . H.,t{./~ ~ ~ I'\LAJI.~~~~ (( Ilo 't:;. /u If i; 7(~ 7t<~~ dc.~ " bvI It ." " 7Id. Nr x:I -(,,; rd ~-'t\.~ ,Q52- H-tA.wD.ii~ ~ C~POSih1 ~1:~ lsf • A,it\'-. D #~"A" b, R~) OI\C:O;~ z.~ h WAil~l~ 0 \h:(AI\~" ~~ JDk~ L. 3c..b~1 K~WA.lOA." ~L K~~lAe 3\'"d II bl Mi ki\'\A. }.J". q.-n. 'I Ktu\.IArlA No De E Wo. i I:t~A C .. b1 cs·H.~r K. \-\ &.4.dJ1 HA \rl "Na. K'kkio Mo.,i" b KAf"ui~c. )A.~~oi<e(,.. iM6-r~ II W" LA-' i t\\oha." b, K. ?U.KLli S~eitJ "-4--\ o...ollAll,(.1I ~ L\o~d. S~Ol'\C .... Co..rol ~Oc.s -:to~ A~I\&'u"'l l:)53 t\tLWAliG-~ s.., c.~po~j~ C6'l\.-t-~ K~ ~ y(~ Jo~\'.. ~\ /s+ (t Y1 4 \' b') \::.. ....eidc.. ll'\~ ,. K~ A\A. A.""'A.l"'-~' II b) ~()l ~OC:5 3rd "fi.\o. )A.o~ fa-kA " b) Kt..~i~e ~~~k~e.. tpl- «Nc."PlAA L.k.< Ok 0 ~ l\i ...~· h" 001. -

The Ukulele Songbook Ebook Free Download

IZ : THE UKULELE SONGBOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Israel Iz Kamakawiwoole | 61 pages | 01 Jul 2011 | Alfred Publishing Co Inc.,U.S. | 9780739080511 | English, Hawaiian | United States Iz : The Ukulele Songbook PDF Book There are items available. Close X. Master the Ukulele 1 Book by Terry Carter. This lets you play any songs that you have downloaded onto your device at a much slower tempo but at the right pitch while you are learning the trickier parts. Outgoing shipments are picked up by our shipping carriers Monday through Friday. Stock photo. This is one of those rare music books that gives you the chance to really grow. You may also enter a personal message. Music Theory Books etc. Love it Verified purchase: Yes Condition: New. Saturday, January 16, Notation and Uke tablature seem to be accurate. Posting Komentar. Diposting oleh Unknown di Learn More - opens in a new window or tab International shipping and import charges paid to Pitney Bowes Inc. Refer to eBay Return policy for more details. Please enter 5 or 9 numbers for the ZIP Code. This name will appear next to your review. View cart Your Wishlist: 0 Items. Visit store. Very satisfied Love the book it was actually in better condition than described. Harrisburg PA retail store. Westminster MD retail store. See details for additional description. If you believe that any review contained on our site infringes upon your copyright, please email us. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. The state flag of Hawaii was flown at half mast as he lay in state at the Hawaiian capitol building. -

Obtaining Hawaiian Artifact Reproduction Kit, Readings For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 199 032 SO 013 102 AUTHOR Hazama, Dorothy, Ed. TTTLE Culture Studies: Hawaiian Studies Project. INSTITUTION Hawaii. State Dept. of rlucation, Honolulu. Office of Instructional Services. REPORT NO RS-79-65?.1 PUB DATE Nov 79 NOTE 138D.: For a related document, see SO 013 101. Some pages are of marginal legibility and will not reproduce clearly- in microfiche or paper copy. EDPS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Education: Elementary Education; *Havaii.ans: Institutes (Training Programs): Instructional Materials: Summer Programs: *Teacher Developed Materials: Teacher Workshops ABSTRACT reports and materials from the Hawaiian Studies ?rolect are presented: The document, designed for elementary school teachers contains two.malor sections. The first section describes the planning phase of the project, the Summer Institute for Hawaiian Culture Studies (1976) and the follow-up workshops and consultant help (1976-77). The appendix to this part lists addresses for obtaining Hawaiian artifact reproduction kit, readings for the summer institute, slides of Hawaiian artifacts, and overhead transparency masters: The second and largest section contains 40 brief readings developed by participants in the summer institute. The topic of each reading is an aspect of Hawaiian culture: each includes illustrations and a reading list. Topics include animals used by Hawaiians, the canoe, fishing, barter, feather-gathering, petroglyphs, gourd water containers, platters, shell trumpets, cultivation, and training for war and weapons used. Indices provide an alphabetized list of teacher information materials and data cards, and a subject matter guide to four. Hawaiian culture information books for studerts. (KC) ****************************ft****************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDPS are the best that can be made from the original document.