Conservation Can Undermine Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

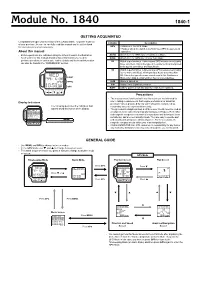

Module No. 1840 1840-1

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy 2014

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy Revised Version 2014.1 Snow Leopard Network 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Snow Leopard Network concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright: © 2014 Snow Leopard Network, 4649 Sunnyside Ave. N. Suite 325, Seattle, WA 98103. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Snow Leopard Network (2014). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Revised 2014 Version Snow Leopard Network, Seattle, Washington, USA. Website: http://www.snowleopardnetwork.org/ The Snow Leopard Network is a worldwide organization dedicated to facilitating the exchange of information between individuals around the world for the purpose of snow leopard conservation. Our membership includes leading snow leopard experts in the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The main goal of this organization is to implement the Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (SLSS) which offers a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing snow leopard conservation today. Cover photo: Camera-trapped snow leopard. © Snow Leopard -

Moüjmtaiim Operations

L f\f¿ áfó b^i,. ‘<& t¿ ytn) ¿L0d àw 1 /1 ^ / / /This publication contains copyright material. *FM 90-6 FieW Manual HEADQUARTERS No We DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 30 June 1980 MOÜJMTAIIM OPERATIONS PREFACE he purpose of this rUanual is to describe how US Army forces fight in mountain regions. Conditions will be encountered in mountains that have a significant effect on. military operations. Mountain operations require, among other things^ special equipment, special training and acclimatization, and a high decree of self-discipline if operations are to succeed. Mountains of military significance are generally characterized by rugged compartmented terrain witn\steep slopes and few natural or manmade lines of communication. Weather in these mountains is seasonal and reaches across the entireSspectrum from extreme cold, with ice and snow in most regions during me winter, to extreme heat in some regions during the summer. AlthoughNthese extremes of weather are important planning considerations, the variability of weather over a short period of time—and from locality to locahty within the confines of a small area—also significantly influences tactical operations. Historically, the focal point of mountain operations has been the battle to control the heights. Changes in weaponry and equipment have not altered this fact. In all but the most extreme conditions of terrain and weather, infantry, with its light equipment and mobility, remains the basic maneuver force in the mountains. With proper equipment and training, it is ideally suited for fighting the close-in battfe commonly associated with mountain warfare. Mechanized infantry can\also enter the mountain battle, but it must be prepared to dismount and conduct operations on foot. -

Natural Resource Damage Valuation

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 42 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1989 Article 1 3-1989 Natural Resource Damage Valuation Frank B. Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Frank B. Cross, Natural Resource Damage Valuation, 42 Vanderbilt Law Review 269 (1989) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol42/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 42 MARCH 1989 NUMBER 2 Natural Resource Damage Valuation Frank B. Cross* Some consume beauty for gain; but all of us must consume it to live.1 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 270 II. LEGAL AUTHORITY FOR GOVERNMENT RECOVERY OF NATURAL RESOURCE DAMAGES ..................................... 273 A. Superfund ...................................... 273 B. The Clean Water Act and Other Federal Laws ..... 276 C. State Statutes and Common Law ................. 277 III. VALUES ATTRIBUTABLE TO NATURAL RESOURCES ........... 280 A . Use Value ...................................... 281 B. Existence Value ................................. 285 C. Intrinsic Value .................................. 292 D. Achieving a True Valuation of Natural Resources .. 297 IV. METHODS FOR MONETIZING DAMAGE TO NATURAL RESOURCES 297 -

Lesson Plan with Activities: Political

LESSON PLAN POLITICAL PARTIES Recommended for Grade 10 Duration: Approximately 60 minutes BACKGROUND INFORMATION Parliamentary Roles: www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/about-ontarios-parliament/ parliamentary-roles LEARNING GOALS This lesson plan is designed to engage students in the political process through participatory activities and a discussion about the various political parties. Students will learn the differences between the major parties of Ontario and how they connect with voters, and gain an understanding of the important elements of partisan politics. INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION (10 minutes) Canada is a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy, founded on the rule of law and respect for rights and freedoms. Ask students which country our system of government is based on. Canada’s parliamentary system stems from the British, or “Westminster,” tradition. Since Canada is a federal state, responsibility for lawmaking is shared among one federal, ten provincial and three territorial governments. Canada shares the same parliamentary system and similar roles as other parliaments in the Commonwealth – countries with historic links to Britain. In our parliament, the Chamber is where our laws are debated and created. There are some important figures who help with this process. Some are partisan and some are non-partisan. What does it mean to be partisan/non-partisan? Who would be voicing their opinions in the Chamber? A helpful analogy is to imagine the Chamber as a game of hockey, where the political parties are the teams playing and the non-partisan roles as the people who make sure the game can happen (ex. referees, announcers, score keepers, etc.) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF ONTARIO POLITICAL PARTIES 01 EXPLANATION (5 minutes) Political Parties: • A political party is a group of people who share the same political beliefs. -

Module No. 2240 2240-1

Module No. 2240 2240-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Precautions • Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial for later reference when necessary. precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as reasonably accurate representations only. About This Manual • Though a useful navigational tool, a GPS receiver should never be used • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to perform as a replacement for conventional map and compass techniques. Remember that magnetic compasses can work at temperatures well operations in each mode. Further details and technical information can also be found in the “REFERENCE”. below zero, have no batteries, and are mechanically simple. They are • The term “watch” in this manual refers to the CASIO SATELLITE NAVI easy to operate and understand, and will operate almost anywhere. For Watch (Module No. 2240). these reasons, the magnetic compass should still be your main • The term “Watch Application” in this manual refers to the CASIO navigation tool. • SATELLITE NAVI LINK Software Application. CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. assumes no responsibility for any loss, or any claims by third parties that may arise through the use of this watch. Upper display area MODE LIGHT Lower display area MENU On-screen indicators L K • Whenever leaving the AC Adaptor and Interface/Charger Unit SAFETY PRECAUTIONS unattended for long periods, be sure to unplug the AC Adaptor from the wall outlet. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

Report of the Select Committee on Electoral Reform

Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM REPORT ON ELECTORAL REFORM 2nd Session, 38th Parliament 54 Elizabeth II Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Ontario. Legislative Assembly. Select Committee on Electoral Reform Report on electoral reform [electronic resource] Issued also in French under title: Rapport de la réforme électorale. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Mode of access: World Wide Web. ISBN 0-7794-9375-3 1. Ontario. Legislative Assembly—Elections. 2. Elections—Ontario. 3. Voting—Ontario. I. Title. JL278 O56 2005 324.6’3’09713 C2005-964015-4 Legislative Assemblée Assembly législative of Ontario de l'Ontario The Honourable Mike Brown, M.P.P., Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. Sir, Your Select Committee on Electoral Reform has the honour to present its Report and commends it to the House. Caroline Di Cocco, M.P.P., Chair. Queen's Park November 2005 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM COMITÉ SPÉCIAL DE LA RÉFORME ÉLECTORALE Room 1405, Whitney Block, Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 SELECT COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL REFORM MEMBERSHIP LIST CAROLINE DI COCCO Chair NORM MILLER Vice-Chair WAYNE ARTHURS KULDIP S. KULAR RICHARD PATTEN MICHAEL D. PRUE MONIQUE M. SMITH NORMAN STERLING KATHLEEN O. WYNNE Anne Stokes Clerk of the Committee Larry Johnston Research Officer i CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Electoral Systems 1 Citizens’ Assembly Terms of Reference 2 Composition of the Assembly 2 Referendum Issues 4 Review of Electoral Reform 5 Future Role 5 List of Recommendations 6 INTRODUCTION 9 Mandate 9 Research Methodology 10 Assessment Criteria 10 Future Role 11 Acknowledgements 11 I. -

Council of the European Union

ISSN 1680-9742 QC-AA-05-001-EN-C EN EN COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION GENERAL SECRETARIAT European Union - Union European EU Annual Report This, the seventh EU Annual Report on Human Rights, records the actions and policies undertaken by the EU between 1 July 2004 and 30 on Human Rights June 2005 in pursuit of its goals to promote universal respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. While not an exhaustive account, it Rights-2005 onHuman Annual Report highlights human rights issues that have given cause for concern and what the EU has done to address these, both within the Union and outside it. 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights 2005 EU Annual Report on Human Rights, adopted by the Council on 3 October 2005. For further information, please contact the Press, Communication and Protocol Division at the following address: General Secretariat of the Council Rue de la Loi 175 B-1048 Brussels Fax: +32 (0)2 235 49 77 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ue.eu.int Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this edition. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2005 ISBN 92-824-3179-7 ISSN 1680-9742 © European Communities, 2005 Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes , provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................7 2. Developments within the EU ...................................................................................................................8 2.1. -

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU

Literature for the SECU Desk Review Dear Paul, Anne and the SECU team, We are writing to you to provide you with what we consider to be important documents in your investigation into community complaints of the Ridge to Reef Project. The following documents provide background to the affected community and the political situation in Tanintharyi Region, on the history and design of the project, on the grievances and concerns of the local community with respect to the project, and aspirations and efforts of indigenous communities who are working towards an alternative vision of conservation in Tanintharyi Region. The documents mentioned in this letter are enclosed in this email. All documents will be made public. Background to the affected community Tanintharyi Region is home to one of the widest expanses of contiguous low to mid elevation evergreen forest in South East Asia, home to a vast variety of vulnerable and endangered flora and fauna species. Indigenous Karen communities have lived within this landscape for generations, managing land and forests under customary tenure systems that have ensured the sustainable use of resources and the protection of key biodiversity, alongside forest based livelihoods. The region has a long history of armed conflict. The area initially became engulfed in armed conflict in December 1948 when Burmese military forces attacked Karen Defence Organization outposts and set fire to several villages in Palaw Township. Conflict became particularly bad in 1991 and 1997, when heavy attacks were launched by the Burmese military against KNU outposts, displacing around 80,000 people.1 Throughout the conflict communities experienced many serious human rights abuses, many villages were burnt down, and tens of thousands of people were forced to flee to the Thai border, the forest or to government controlled zones.2 Armed conflict came to a halt in 2012 following a bi-lateral ceasefire agreement between the KNU and the Myanmar government, which was subsequently followed by KNU signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in 2015. -

Country Strategy Paper Nepal 2007-2013

NEPAL Country Strategy Paper 2007 – 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................... 1 1. OVERVIEW OF COOPERATION AND POLICY DIALOGUE, COMPLEMENTARITY AND CONSISTENCY............................................................... 2 1.1 OVERVIEW OF PAST AND PRESENT EC COOPERATION (LESSONS LEARNED).................................... 2 1.2 INFORMATION ON THE PROGRAMMES OF OTHER DONORS.............................................................. 4 1.3 STATE OF POLITICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE DONORS AND NEPAL ............................................ 4 1.4 ANALYSIS OF POLICY COHERENCE FOR DEVELOPMENT ................................................................... 4 2. THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION’S RESPONSE STRATEGY.............................. 5 2.1 JUSTIFICATION OF THE CHOICE OF THE FOCAL SECTORS.................................................................. 5 2.3 IMPLEMENTATION: THE WORK PROGRAMME .................................................................................... 7 ANNEXES ..........................................................................................................................10 ANNEX I: FRAMEWORK OF RELATIONS BETWEEN THE EC AND NEPAL......11 ANNEX II: COUNTRY DIAGNOSIS...............................................................................14 1. ANALYSIS OF THE POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL, AND ENVIRONMENTAL SITUATION ................ 14 1.1 Political situation .........................................................................................................................14 -

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment ASEAN Disaster Risk Management Initiative December 2010 Preface The countries of the Association of Southeast (Vietnam) droughts, September 2009 cyclone Asian Nations (ASEAN), which comprises Brunei, Ketsana (known as Ondoy in the Philippines), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, catastrophic flood of October 2008, and January Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, is 2007 flood (Vietnam), September 1997 forest-fire geographically located in one of the most disaster (Indonesia) and many others. Climate change is prone regions of the world. The ASEAN region expected to exacerbate disasters associated with sits between several tectonic plates causing hydro-meteorological hazards. earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis. The region is also located in between two great Often these disasters transcend national borders oceans namely the Pacific and the Indian oceans and overwhelm the capacities of individual causing seasonal typhoons and in some areas, countries to manage them. Most countries in tsunamis. The countries of the region have a the region have limited financial resources and history of devastating disasters that have caused physical resilience. Furthermore, the level of economic and human losses across the region. preparedness and prevention varies from country Almost all types of natural hazards are present, to country and regional cooperation does not including typhoons (strong tropical cyclones), exist to the extent necessary. Because of this high floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, vulnerability and the relatively small size of most landslides, forest-fires, and epidemics that of the ASEAN countries, it will be more efficient threaten life and property, and droughts that leave and economically prudent for the countries to serious lingering effects.