ISANG YUN Oktett (1978)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turismus V Bydhošti. Kulturní a Jazykové Bariéry

VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA Obor: Cestovní ruch Turismus v Bydhošti. Kulturní a jazykové bariéry bakalářská práce Autor: Miroslav Danko Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Jitka Ryšková Jihlava 2013 Prohlašuji, že předložená bakalářská práce je původní a zpracoval jsem ji samostatně. Prohlašuji, že citace použitých pramenů je úplná, že jsem v práci neporušil autorská práva (ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů, v platném znění, dále též „AZ“). Souhlasím s umístěním bakalářské práce v knihovně VŠPJ a s jejím užitím k výuce nebo k vlastní vnitřní potřebě VŠPJ . Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že na mou bakalářskou práci se plně vztahuje AZ, zejména § 60 (školní dílo). Beru na vědomí, že VŠPJ má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití mé bakalářské práce a prohlašuji, že s o u h l a s í m s případným užitím mé bakalářské práce (prodej, zapůjčení apod.). Jsem si vědom toho, že užít své bakalářské práce či poskytnout licenci k jejímu využití mohu jen se souhlasem VŠPJ, která má právo ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, vynaložených vysokou školou na vytvoření díla (až do jejich skutečné výše), z výdělku dosaženého v souvislosti s užitím díla či poskytnutím licence. V Jihlavě dne 10. května 2013 ...................................................... Podpis I would like to express my gratitude towards my supervisor RNDr. Jitka Ryšková for her help with my bachelor thesis. I am greatful for the time she spent supervising my work and all of the advice she give me. I wish to thank Mr. Jan Karol Słowinski who supervised and helped me with my thesis during my stay in Poland. -

Nicole Mieske Knab for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Marketing & Communications Coordinator Piano Cleveland 216-707-5397 [email protected]

Contact: Nicole Mieske Knab FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Marketing & Communications Coordinator Piano Cleveland 216-707-5397 [email protected] Piano Cleveland’s Highly Viewed Virtual Competition Concludes with Top Winners Announced at Awards Ceremony After 12 days of brilliant performances and over $62,000 raised for artists, Martin James Bartlett has been named First Prize Winner of Virtu(al)oso. CLEVELAND, OH – August 10, 2020 After a total of 12 days, 36 performances, and 72 hours of streamed content, Martin James Bartlett has been named the First Prize Winner of Virtu(al)oso, Piano Cleveland’s global competition for artist relief presented in artistic partnership with Steinway & Sons. The six-member jury of leaders in the piano world gathered virtually over the weekend to select the top three prize winners, and the announcement was broadcast during the Awards Ceremony on August 9, 2020. The decision came after 30 contestants hailing from 18 different countries recorded two short programs of their choice with contrasting styles from Steinway locations in Cleveland, New York, London, Hamburg, and Beijing. Six pianists advanced to the Final Round where they performed 30-minute recitals, vetted by a remote jury of renowned artists including Libby Abrahams, Darrell Ang, Adam Gatehouse, Steinway Artist Olga Kern, Gabriela Montero, and Steinway Artist Pierre van der Westhuizen. “What a thrill to be involved with this brave, unique venture!” said Adam Gatehouse, Competition Juror and Artistic Director of the Leeds International Piano -

557981 Bk Szymanowski EU

570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 16 Karol Also available: SZYMANOWSKI Harnasie (Ballet-Pantomime) Mandragora • Prince Potemkin, Incidental Music to Act V Ochman • Pinderak • Marciniec Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir • Antoni Wit 8.557981 8.570721 8.570723 16 570723 bk Szymanowski EU:570723 bk Szymanowski EU 12/15/08 5:13 PM Page 2 Karol SZYMANOWSKI Also available: (1882-1937) Harnasie, Op. 55 35:47 Text: Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) and Jerzy Mieczysław Rytard (1899-1970) Obraz I: Na hali (Tableau I: In the mountain pasture) 1 No. 1: Redyk (Driving the sheep) 5:09 2 No. 2: Scena mimiczna (zaloty) (Mimed Scene (Courtship)) 2:15 3 No. 3: Marsz zbójnicki (The Tatra Robbers’ March)* 1:43 4 No. 4: Scena mimiczna (Harna i Dziewczyna) (Mimed Scene (The Harna and the Girl))† 3:43 5 No. 5: Taniec zbójnicki – Finał (The Tatra Robbers’ Dance – Finale)† 4:42 Obraz II: W karczmie (Tableau II: In the inn) 6 No. 6a: Wesele (The Wedding) 2:36 7 No. 6b: Cepiny (Entry of the Bride) 1:56 8 No. 6c: Pie siuhajów (Drinking Song) 1:19 9 No. 7: Taniec góralski (The Tatra Highlanders’ Dance)* 4:20 0 No. 8: Napad harnasiów – Taniec (Raid of the Harnasie – Dance) 5:25 ! No. 9: Epilog (Epilogue)*† 2:39 Mandragora, Op. 43 27:04 8.557748 Text: Ryszard Bolesławski (1889-1937) and Leon Schiller (1887-1954) @ Scene 1**†† 10:38 # Scene 2†† 6:16 $ Scene 3** 10:10 % Knia Patiomkin (Prince Potemkin), Incidental Music to Act V, Op. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Festival Artists

Festival Artists Cellist OLE AKAHOSHI (Norfolk competitions. Berman has authored two books published by the ’92) performs in North and South Yale University Press: Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas: A Guide for the Listener America, Asia, and Europe in recitals, and the Performer (2008) and Notes from the Pianist’s Bench (2000; chamber concerts and as a soloist electronically enhanced edition 2017). These books were translated with orchestras such as the Orchestra into several languages. He is also the editor of the critical edition of of St. Luke’s, Symphonisches Orchester Prokofiev’s piano sonatas (Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2011). Berlin and Czech Radio Orchestra. | 27th Season at Norfolk | borisberman.com His performances have been featured on CNN, NPR, BBC, major German ROBERT BLOCKER is radio stations, Korean Broadcasting internationally regarded as a pianist, Station, and WQXR. He has made for his leadership as an advocate for numerous recordings for labels such the arts, and for his extraordinary as Naxos. Akahoshi has collaborated with the Tokyo, Michelangelo, contributions to music education. A and Keller string quartets, Syoko Aki, Sarah Chang, Elmar Oliveira, native of Charleston, South Carolina, Gil Shaham, Lawrence Dutton, Edgar Meyer, Leon Fleisher, he debuted at historic Dock Street Garrick Ohlsson, and André-Michel Schub among many others. Theater (now home to the Spoleto He has performed and taught at festivals in Banff, Norfolk, Aspen, Chamber Music Series). He studied and Korea, and has given master classes most recently at Central under the tutelage of the eminent Conservatory Beijing, Sichuan Conservatory, and Korean National American pianist, Richard Cass, University of Arts. -

ASIAN SYMPHONIES a Discography of Cds and Lps Prepared By

ASIAN SYMPHONIES A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis KOMEI ABE (1911-2006, JAPAN) Born in Hiroshima. He studied the cello with Heinrich Werkmeister at the Tokyo Music School and then studied German-style harmony and counterpoint with Klaus Pringsheim, a pupil of Gustav Mahler, as well as conducting with Joseph Rosenstock. Later, he was appointed music director of the Imperial Orchestra in Tokyo, and the musicians who played under him broadened his knowledge of traditional Japanese Music. He then taught at Kyoto's Elizabeth Music School and Municipal College of the Arts. He composed a significant body of orchestral, chamber and vocal music, including a Symphony No. 2 (1960) and Piccolo Sinfonia for String Orchestra (1984). Symphony No. 1 (1957) Dmitry Yablonsky/Russian National Philharmonic ( + Sinfonietta and Divertimento) NAXOS 8.557987 (2007) Sinfonietta for Orchestra (1964) Dmitry Yablonsky/Russian National Philharmonic ( + Sinfonietta and Divertimento) NAXOS 8.557987 (2007) NICANOR ABELARDO (1896-1934, PHILIPPINES) Born in San Miguel, Bulacan. He studied at the University of the Philippines Diliman Conservatory of Music, taking courses under Guy Fraser Harrison and Robert Schofield. He became head of the composition department of the conservatory in 1923. He later studied at the Chicago Musical College in 1931 under Wesley LaViolette. He composed orchestral and chamber works but is best-known for his songs. Sinfonietta for Strings (1932) Ramon Santos/Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES PRESS (2004) YASUSHI AKUTAGAWA (1925-1989, JAPAN) He was born in the Tabata section of Tokyo. He was taught composition by Kunihiko Hashimoto and Akira Ifukube at the Tokyo Conservatory of Music. -

Anna Gutowska

Anna Gutowska was born in Rzeszow. From the age of seven, she attended the music school from which she graduated with honors. After attending the piano class of Prof. L. Strzelecka for one year, she started to learn to play the violin at the violin class of Prof. D.Sendłak. After graduation, Anna continued teaching in the Music School Association in Rzeszow in the class of Prof. R. Naściszewski, while at the same time, she was a student at the Conservatoire de Lausanne in Switzerland in the class of Prof. J. Jaquerod. She also graduated from this course with distinction. From 2001 she studied at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna in the violin class - concert subject of o.Univ. Prof. Edward Zienkowski. In 2007 she received her diploma with distinction and a prize from the Minister for Culture and Art and acquired the title Mag. Art. In 2008/2009, she completed postgraduate studies at the same university under supervision of Prof. Edward Zienkowski. Anna took part in the International Z.Brzewski Master Classes in Łańcut, the Verbier Festival Academy, the Vienna Master Classes and others, each under supervision of valued virtuosos and educators such as I. Haendel, I. Ojstrach, M. Jaszwili, H .Krebbers, KAKulka, P.Urstein, J.Kaliszewska, M.Ławrynowicz, P.Farulli (Quartetto Italiano). She is the winner of numerous Polish and international competitions, such as: - Special prize of the Henryk Wieniawski Society at the Polish St. Serwaczyński Violin Competition in Lublin (1996) - first prize in the young talent competition in -

Sports in Bydgoszcz Bydgoszcz Specialties

N i e c a ł a C z Kąpielowa R a ó Wr r żan ocław n a ska a D r o g a Old Bydgoszcz Canal Stary Kanał Bydgoski Stary Kanał S z u Canal Bydgoszcz b J a Bydgoski Kanał i sn ń a s 26 k a Bydgoszcz Specialties SportsŻ in Bydgoszcz e g l a r s k G a ra nic L S zn udw t a ro Grunw m P i a k R It should be added that a new, modern marina with a hotel was built on Mill During your stay in Bydgoszcz, it’s worth fi nding time to try local specialties. oznański K ow r Plac u s z w ondo a i c k Bread with potatoes aldzkie o Island, in the city centre. The Regional Rowing Association LOTTO-Bydgostia There is something for everyone, including chocolates, goose meat, locally Beer from the local brewery Potato rye bread is one of the oldest culinary recipes from the Bydgoszcz The traditions of Bydgoszcz brewing date back to the origins of the city. In the (RTW), the successor of the Railway Rowing Club, is a prominent rowing orga- brewed beer, and bread with potatoes … area. In the past, bread was baked from fl our processed at a farm or pur- 14th century, every townsman, owner of a lot within the city walls, had the right H. Dąbrowskiego nization. RTW is a 25-time (until 2013) Team Champion of Poland. It has been S iem ira chased from the mill. -

THE MAESTRO in OUR MIDST Prominent Polish Conductor Antoni Wit Has Striven to Keep the Polish Repertory Alive Throughout His Illustrious Career

Antoni Wit THE MAESTRO IN OUR MIDST Prominent Polish conductor Antoni Wit has striven to keep the Polish repertory alive throughout his illustrious career. We take a look at the achievements of the acclaimed conductor, ahead of his performances with the Symphony Orchestra of India. By Beverly Pereira MESSIAS JOÃO | MÚSICA DA CASA hen the Warsaw Philharmonic ensemble performed close to 600 concerts, embarked Having managed and conducted a host of renowned with the Silver Cross of Merit in Poland and had the Orchestra made its debut at on international tours and contributed an astonishingly Polish and international orchestras, one wonders distinction of being named Chevalier of the French the BBC Proms, in August large catalogue of recordings – almost 100 albums – whether Wit has observed any obvious differences in Legion of Honour for his services in the promotion of 2013, the evening was charged to the Naxos recording label. Between 1987 and 1992, orchestral personalities. “When I was much younger, French music. with a sense of serendipity and he was simultaneously engaged with the Orquesta I was able to see more differences in orchestras, first Come this year, the maestro says he has plans to synchronicity. The orchestra Filarmónica de Gran Canaria as its artistic director. of all because of the nationalities of their musicians. record Catalan music. Besides recording in Barcelona performed Witold Lutosławski’s He also taught conducting at the Fryderyk Chopin Now, with globalisation, there in 2018, he is looking forward Concerto for Orchestra – University of Music in Warsaw from 1998 through 2014. are fewer differences. Orchestras to the release of a recording W incidentally composed for the All this, while actively embracing the schedules and are more international, but some A champion of Polish of Brahms concertos (violin very same orchestra, albeit from 1950-1954. -

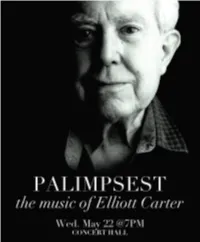

20130522-Palimpsest2.Pdf

UC San Diego • Division of Arts and Humanities • Department of Music presents Dean’s Night at the Prebys Palimpsest The Music of Elliott Carter Conducted by Donald Palma / Curated by Aleck Karis Double Trio (2011) Leah Asher, violin Judith Hamann, cello Calvin Price, trumpet Eric Starr, trombone Kyle Blair, piano Stephen Solook, percussion colla voce by Stephen Lewis (world premiere) (2013) Tiffany DuMouchelle, soprano Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Leah Asher, viola Jennifer Bewerse, cello Scott Worthington, bass Christine Tavolacci, flute Jonathan Davis, oboe Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Todd Moellenberg, piano Ryan Nestor, percussion Triple Duo (1983) Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Judith Hamann, cello Rachel Beetz, flute Curt Miller, clarinet Kyle Adam Blair, piano Jonathan Hepfer, percussion intermission Hiyoku (2001) Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Curt Miller, clarinet Elliott’s Instruments by Rand Steiger (2010) Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Judith Hamann, cello Rachel Beetz, flute Curt Miller, clarinet Kyle Adam Blair, piano Jonathan Hepfer, percussion A Mirror on Which to Dwell (1975) Alice Teyssier, soprano Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Leah Asher, viola Jennifer Bewerse, cello Scott Worthington, bass Christine Tavolacci, flute Jonathan Davis, oboe Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Todd Moellenberg, piano Ryan Nestor, percussion PRORGRAM NOTES Remembering Elliott Carter Composer Elliott Carter passed away November 5, 2012 just five weeks short of his 104th birthday. In recent years, from his perch above West 12th Street, flowed a most remarkable steam of works of imagination, craft, wit and humanity. It seemed the older he became the more he had to say. And the more the world wanted to listen. Many of us had the great privilege of working very closely with Elliott in numerous orchestral, chamber and solo settings. -

October 12, 2017: (Full-Page Version) Close Window “Don't Be Too Timid and Squeamish About Your Actions

October 12, 2017: (Full-page version) Close Window “Don't be too timid and squeamish about your actions. All life is an experiment.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Liszt Ballade No. 1 in D flat Stephen Hough Hyperion 67085 034571170855 Awake! 00:09 Buy Now! Mozart String Quartet No. 23 in F, K. 590 Shanghai Quartet Delos 3192 013491319223 00:39 Buy Now! Lully Ballet de Xerxes Aradia Baroque Ensemble/Mallon Naxos 8.554003 636943400326 Vaughan Serenade to Music (for 16 soloists & Corydon Singers/English Chamber 01:00 Buy Now! Hyperion 66420 034571164205 Williams orchestra) Orch/Best 01:15 Buy Now! Taylor, Deems Through the Looking Glass Seattle Symphony/Schwarz Delos 3099 013491309927 01:48 Buy Now! Schumann Three Romances for Clarinet, Op. 94 Neidich/Hokanson Sony 48035 07464480352 Pavarotti/English Chamber 02:02 Buy Now! Donizetti Una furtiva lagrima ~ L'elisir d'amore London 417 011 028941701121 Orchestra/Bonynge 02:08 Buy Now! Schubert Symphony No. 9 in C, D. 944 "Great" Royal Concertgebouw/Bernstein DG 289 477 5167 028947751670 03:00 Buy Now! Willan Rise up my love Choir of St. John's, Elora/Edison Naxos www.theclassicalstation.org n/a 03:03 Buy Now! Chopin Two Bourees Cyprien Katsaris Sony 53355 074645335520 03:06 Buy Now! Paderewski Symphony in B minor, "Polania" Pomeranian Philharmonic/Wosiczko Olympia 305 5015524003050 Amsterdam Baroque 04:00 Buy Now! Handel Concerto Grosso in G minor, Op. 6 No. 6 Erato 75357 08908853572 Orchestra/Koopman 04:16 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. -

572032 Bk Penderecki

GÓRECKI Concerto-Cantata Little Requiem for a Certain Polka • Three Dances Harpsichord Concerto (piano version) Anna Górecka, Piano • Carol Wincenc, Flute Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (1933-2010): Little Requiem for a Certain Polka presence as the work heads to a rapt close with just the The first movement opens with a coursing motion for Concerto-Cantata • Harpsichord Concerto (piano version) • Three Dances quietest of discords on piano then bells to recall earlier unison strings with piano providing a no less intensive events. accompaniment. This continues on its purposeful course Henryk Mikołaj Górecki was born on 6th December 1933 followed by the monumental Miserere for unaccompanied Completed barely a year before, Concerto-Cantata with just the occasional pause until reaching a held in Czernica, Silesia. He studied music at the High School voices (1981), written in support of the Polish trade union (1992) for flute and orchestra was given a first hearing in cadential chord from which the second movement sets off (now Academy) of Music in Katowice, graduating with Solidarity, while chamber music was represented by such Amsterdam on 28th November 1992 by Carol Wincenc with a vaunting idea for the soloist against mock-Classical distinction in 1960 from the class of Bolesław Szabelski pieces as Lerchenmusik (1986) and three string quartets with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and figuration on strings. This duly takes in passages of (who had been taught by Szymanowski). Górecki gave his composed for the Kronos Quartet between 1988 and Eri Klas. The hybrid title is explained by its movements contrasting harmonic profile without disrupting the début concert as a composer in 1958 in Katowice, which 1995.