Understanding Style and Identity in the Mediterranean Oikoumene The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

341 BC the THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes Translated By

1 341 BC THE THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes translated by Thomas Leland, D.D. Notes and Introduction by Thomas Leland, D.D. 2 Demosthenes (383-322 BC) - Athenian statesman and the most famous of Greek orators. He was leader of a patriotic party opposing Philip of Macedon. The Third Philippic (341 BC) - The third in a series of speeches in which Demosthenes attacks Philip of Macedon. Demosthenes urged the Athenians to oppose Philip’s conquests of independent Greek states. Cicero later used the name “Philippic” to label his bitter speeches against Mark Antony; the word has since come to stand for any harsh invective. 3 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC INTRODUCTION To the Third Philippic THE former oration (The Oration on the State of the Chersonesus) has its effect: for, instead of punishing Diopithes, the Athenians supplied him with money, in order to put him in a condition of continuing his expeditions. In the mean time Philip pursued his Thracian conquests, and made himself master of several places, which, though of little importance in themselves, yet opened him a way to the cities of the Propontis, and, above all, to Byzantium, which he had always intended to annex to his dominions. He at first tried the way of negotiation, in order to gain the Byzantines into the number of his allies; but this proving ineffectual, he resolved to proceed in another manner. He had a party in the city at whose head was the orator Python, that engaged to deliver him up one of the gates: but while he was on his march towards the city the conspiracy was discovered, which immediately determined him to take another route. -

Comune Di S. Giovanni Incarico PROVINCIA DI FROSINONE

Comune di S. Giovanni Incarico PROVINCIA DI FROSINONE PIANO DI EMERGENZA DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE AGGIORNAMENTO DEL PIANO DI EMERGENZA COMUNALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE AI SENSI DELLA D.G.R.L. 363/2014 – 415/2015 RELAZIONE TECNICA Data, 30/11/2016 APPROVATO CON D.C.C. N° 27 DEL 02/12/2016 RESPONSABILE LAVORI PUBBLICI ARCH. ANNA MARIA CAMPAGNA PROFESSIONISTA INCARICATO ING. MASSIMO PATRIZI PREMESSA Il Piano Comunale di Emergenza di Protezione Civile, è stato elaborato con lo scopo di fornire al Comune uno strumento operativo utile a fronteggiare l’emergenza locale, conseguente al verificarsi di eventi naturali o connessi con l'attività dell'uomo; ci si riferisce ad eventi che per loro natura ed estensione possono essere contrastati mediante interventi attuabili autonomamente dal Comune, dalla Regione e della Provincia in quanto titolari dei Programmi di previsione e prevenzione. Il presente Piano di Emergenza, obbligatorio a norma di legge, è uno strumento a forte connotazione tecnica, fondato sulla conoscenza delle pericolosità e dei rischi che investono il territorio comunale e, nella prospettiva offerta dalla legislazione, esso trova una chiara collocazione tra gli strumenti che l’Ente ha a disposizione per la gestione dei rischi. Sulla base di scenari di riferimento, individua e disegna le diverse strategie finalizzate alla riduzione del danno ovvero al superamento dell'emergenza ed ha come finalità prioritaria la salvaguardia delle persone, dell’ambiente e dei beni presenti in un'area a rischio. Il Piano include quegli elementi informativi concernenti le condizioni di rischio locale che debbono essere recepite, e in alcuni casi risolte, dalla pianificazione territoriale. Nel caso di grosse calamità il Piano rappresenta lo strumento di primo intervento e di prima gestione dell’emergenza. -

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes

The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Table of Contents The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes..............................................................................................1 Charles Rann Kennedy...................................................................................................................................1 THE FIRST OLYNTHIAC............................................................................................................................1 THE SECOND OLYNTHIAC.......................................................................................................................6 THE THIRD OLYNTHIAC........................................................................................................................10 THE FIRST PHILIPPIC..............................................................................................................................14 THE SECOND PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................21 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC.............................................................................................................................25 THE FOURTH PHILIPPIC.........................................................................................................................34 i The Olynthiacs and the Phillippics of Demosthenes Charles Rann Kennedy This page copyright © 2002 Blackmask Online. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

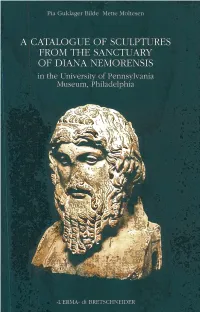

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

![The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9825/the-history-of-rome-vol-4-10-ad-199825.webp)

The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Vol. 4 [10 AD] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Mediterranean Divine Vintage Turkey & Greece

BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Neapolis Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Abdera Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA JOINAllante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Elimia PydnaMEDITERRANEAN Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Dasaki Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos Torone Hephaistia Dorylaeum BOZCAADA Sigeion Kenchreai Omphatium Gonnus Skione Limnos MYSIA Uludag ESKİŞEHİR Eritium DIVINE VINTAGE Derecik Basilica Sidari Oxynia Myrina Kaz Mt. Passaron Soufli Troas Kebrene Skepsis UNESCO Meliboea Cassiope Gure bath BALIKESİR Dikilitaş Kanlıtaş Höyük Aiginion Neandra Karacahisar Castle Meteora Antandros Adramyttium Corfu UNESCO Larissa Lamponeia Dodoni Theopetra Gülpinar Pioniai Kulluoba Hamaxitos Seyitömer Höyük Keçi çayırı Syvota KÜTAHYA Grava Polimedion Assos Gerdekkaya Assos Mt.Pelion A E GTURKEY E A N S E A &Pyrrha GREECEMadra Mt. (Cotiaeum) Kumbet Lefkimi Theudoria Pherae Mithymna Midas City Ellina EPIRUS Passandra Perperene Lolkos/Gorytsa Antissa Bahses Mt. -

La Latinità Di Ariccia E La Grecità Di Nemi. Istituzioni Civili E Religiose a Confronto

ANNA PASQUALINI La latinità di Ariccia e la grecità di Nemi. Istituzioni civili e religiose a confronto Il titolo del mio intervento è solo apparentemente contraddittorio. Esso è volto a mettere in relazione due contesti sociali tanto vicini nello spazio quanto distanti per impianto culturale e per funzioni politiche: la città di Ariccia e il lucus Dianius. Del bosco sacro a Diana e della selva che lo circonda si è scritto moltissimo soprattutto da quando esso costituì il fulcro di un’opera straordinaria per ricchezza ed originalità quale quella di Sir James Frazer1 Su Ariccia, invece, come comunità cittadina e sulle sue istituzioni politiche e religiose non si è riflettuto abbastanza2 e, in particolare, queste ultime non sono state messe sufficientemente in relazione con il santuario nemorense. Cercherò, quindi, di svolgere qualche considerazione nella speranza di fornire un piccolo contributo alla definizione degli intricati problemi del territorio aricino. Ariccia, come comunità politica, appare nelle fonti letterarie all’epoca del secondo Tarquinio, il tiranno per eccellenza, spregiatore del Senato e del popolo3. Al Superbo viene attribuita una forte vocazione al controllo politico del Lazio attraverso un’accorta rete di alleanze con i maggiorenti del Lazio, primo fra tutti il più eminente di essi, e cioè Ottavio Mamilio di Tuscolo, che è anche suo genero (Livio I 49); è ancora Tarquinio che, secondo le fonti (Livio I 50), indirizza la politica dei Latini convocando i federati in assemblea presso il lucus sacro a Ferentina4. La scelta del luogo non è casuale. Il bosco sacro è stato localizzato nel territorio di Ariccia, ma esso viene considerato idealmente collegato con il Monte Albano, cioè con il centro sacrale dei Latini, 1 La prima edizione dell’opera, The Golden Bough, risale al 1890. -

Philip II of Macedon: a Consideration of Books VII IX of Justin's Epitome of Pompeius Trogus

Durham E-Theses Philip II of Macedon: a consideration of books VII IX of Justin's epitome of Pompeius Trogus Wade, J. S. How to cite: Wade, J. S. (1977) Philip II of Macedon: a consideration of books VII IX of Justin's epitome of Pompeius Trogus, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10215/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. PHILIP II OF MACEDON: A CONSIDERATION OF BOOKS VII - IX OF JUSTIN* S EPITOME OF POMPEIUS TROGUS THESIS SUBMITTED IN APPLICATION FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS - by - J. S. WADE, B. A. DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM OCTOBER 1977 ABSTRACT The aim of this dissertation is two-fold: firstly to examine the career and character of Philip II of Macedon as portrayed in Books VII - IX of Justin's epitome of the Historiae Phillppicae .of Pompeius Trqgus, and to consider to what extent Justin-Trogus (a composite name for the author of the views in the text of Justin) furnishes accurate historical fact, and to what extent he paints a one-sided interpretation of the events, and secondly to identify as far as possible Justin's principles of selection and compression as evidenced in Books VII - IX. -

The Roman Army's Emergence from Its Italian Origins

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE ROMAN ARMY’S EMERGENCE FROM ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Richard Talbert Nathan Rosenstein Daniel Gargola Fred Naiden Wayne Lee ABSTRACT PATRICK ALAN KENT: The Roman Army’s Emergence from its Italian Origins (Under the direction of Prof. Richard Talbert) Roman armies in the 4 th century and earlier resembled other Italian armies of the day. By using what limited sources are available concerning early Italian warfare, it is possible to reinterpret the history of the Republic through the changing relationship of the Romans and their Italian allies. An important aspect of early Italian warfare was military cooperation, facilitated by overlapping bonds of formal and informal relationships between communities and individuals. However, there was little in the way of organized allied contingents. Over the 3 rd century and culminating in the Second Punic War, the Romans organized their Italian allies into large conglomerate units that were placed under Roman officers. At the same time, the Romans generally took more direct control of the military resources of their allies as idea of military obligation developed. The integration and subordination of the Italians under increasing Roman domination fundamentally altered their relationships. In the 2 nd century the result was a growing feeling of discontent among the Italians with their position.