Religious Pluralism in Indonesia Harmonious Traditions Face Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Language Attitudes of Madurese People and the Prospects of Madura Language Akhmad Sofyan Department of Humanities, University of Jember, Jember, Indonesia

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 4(9): 3934-3938, 2017 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v4i9.06 ICV 2015:45.28 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2017, THEIJSSHI Research Article The Language Attitudes of Madurese People and the Prospects of Madura Language Akhmad Sofyan Department of Humanities, University of Jember, Jember, Indonesia Abstract: Due to Madurese language behavior that does not have a positive attitude towards the language, Madurese has changed a lot. Many of the uniqueness of Madura language that is not used in the speech, replaced with the Indonesian language. Recently, in Madura language communication, it is found the use of lexical elements that are not in accordance with the phonological rules of Madura Language. Consequently, in the future, Madura language will increasingly lose its uniqueness as a language, instead it will appear more as a dialect of the Indonesian language. Nowadays, the insecurity of Madura language has begun to appear with the shrinking use of this language in communication. Therefore, if there is no a very serious and planned effort, Madura language will be extinct soon; No longer claimed as language, but will only become one of the dialects of the Indonesian language. Keywords: language change, uniqueness, dialectic, speech level, development. INTRODUCTION enjâ'-iyâ (the same type of ngoko speech in Javanese), Madura language is a local language that is used as a medium engghi-enten (The same type of krama madya in Javanese), of daily communication by Madurese people, both for those and èngghi-bhunten (the same type of krama inggil in who live in Madura Island and small islands around it and Javanese); Which Madurese people call ta’ abhâsa, bhâsa those who live in overseas. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 473 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social Sciences (ICSS 2020) The Development of Smart Travel Guide Application in Madura Tourism A Jauhari1* F A Mufarroha Moch Rofi’ 1 1 1Departement of Informatic Departement of Informatic Departement of Informatic Engineering, Engineering, Engineering, University of Trunojoyo Madura University of Trunojoyo Madura University of Trunojoyo Madura Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Muhammad Fikri Nasrullah Fitriyah Khoirun Nisa 1Departement of Informatic 1Departement of Informatic 1Departement of Informatic Engineering, Engineering, Engineering, University of Trunojoyo Madura University of Trunojoyo Madura University of Trunojoyo Madura Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia Bangkalan – Madura, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] technology used by modern society is now Abstract—The development of technology more based on smartphone technology. The experienced very rapid growth. One of the benefits of smartphones as a communication benefits of this is the use of smart phones that are medium that is easy to use for example widely used by the public in making it easier to smartphones connecting several people, users carry out daily activities. the purpose of our can watch videos, play games, listen to music, research is to promote tourism to the outside world by utilizing smart cellphones as a platform pay online and others [1]. Based on data on the for its introduction. The tourism we introduce is status counter as of March 2020, smartphone Madura Island, which is one of Indonesia's operating systems that are widely used by the islands. -

Helicobacter Pylori in the Indonesian Malay's Descendants Might Be

Syam et al. Gut Pathog (2021) 13:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-021-00432-6 Gut Pathogens RESEARCH Open Access Helicobacter pylori in the Indonesian Malay’s descendants might be imported from other ethnicities Ari Fahrial Syam1†, Langgeng Agung Waskito2,3†, Yudith Annisa Ayu Rezkitha3,4, Rentha Monica Simamora5, Fauzi Yusuf6, Kanserina Esthera Danchi7, Ahmad Fuad Bakry8, Arnelis9, Erwin Mulya10, Gontar Alamsyah Siregar11, Titong Sugihartono12, Hasan Maulahela1, Dalla Doohan2, Muhammad Miftahussurur3,12* and Yoshio Yamaoka13,14* Abstract Background: Even though the incidence of H. pylori infection among Malays in the Malay Peninsula is low, we observed a high H. pylori prevalence in Sumatra, which is the main residence of Indonesian Malays. H. pylori preva- lence among Indonesian Malay descendants was investigated. Results: Using a combination of fve tests, 232 recruited participants were tested for H- pylori and participants were considered positive if at least one test positive. The results showed that the overall H. pylori prevalence was 17.2%. Participants were then categorized into Malay (Aceh, Malay, and Minang), Java (Javanese and Sundanese), Nias, and Bataknese groups. The prevalence of H. pylori was very low among the Malay group (2.8%) and no H. pylori was observed among the Aceh. Similarly, no H. pylori was observed among the Java group. However, the prevalence of H. pylori was high among the Bataknese (52.2%) and moderate among the Nias (6.1%). Multilocus sequence typing showed that H. pylori in Indonesian Malays classifed as hpEastAsia with a subpopulation of hspMaori, suggesting that the isolated H. pylori were not a specifc Malays H. -

Religious Specificities in the Early Sultanate of Banten

Religious Specificities in the Early Sultanate of Banten (Western Java, Indonesia) Gabriel Facal Abstract: This article examines the religious specificities of Banten during the early Islamizing of the region. The main characteristics of this process reside in a link between commerce and Muslim networks, a strong cosmopolitism, a variety of the Islam practices, the large number of brotherhoods’ followers and the popularity of esoteric practices. These specificities implicate that the Islamizing of the region was very progressive within period of time and the processes of conversion also generated inter-influence with local religious practices and cosmologies. As a consequence, the widespread assertion that Banten is a bastion of religious orthodoxy and the image the region suffers today as hosting bases of rigorist movements may be nuanced by the variety of the forms that Islam took through history. The dominant media- centered perspective also eludes the fact that cohabitation between religion and ritual initiation still composes the authority structure. This article aims to contribute to the knowledge of this phenomenon. Keywords: Islam, Banten, sultanate, initiation, commerce, cosmopolitism, brotherhoods. 1 Banten is well-known by historians to have been, during the Dutch colonial period at the XIXth century, a region where the observance of religious duties, like charity (zakat) and the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj), was stronger than elsewhere in Java1. In the Indonesian popular vision, it is also considered to have been a stronghold against the Dutch occupation, and the Bantenese have the reputation to be rougher than their neighbors, that is the Sundanese. This image is mainly linked to the extended practice of local martial arts (penca) and invulnerability (debus) which are widespread and still transmitted in a number of Islamic boarding schools (pesantren). -

East Java: Deadheat in a Battleground Province

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 058 – 27 March 2019 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical and contemporary issues. The authors’ views are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email to Mr Yang Razali Kassim, Editor RSIS Commentary at [email protected]. Indonesian Presidential Election 2019 East Java: Deadheat in a Battleground Province By Alexander R. Arifianto and Jonathan Chen SYNOPSIS Home to roughly 31 million eligible voters, both President Joko Widodo and his opponent Prabowo Subianto are currently locked in a statistical deadheat in East Java – a key province in which the winner is likely to become Indonesia’s next president. COMMENTARY FOR BOTH contenders of the 2019 presidential election – incumbent President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo and his challenger Prabowo Subianto − East Java is a “must win” province. East Java has a total population of 42 million − including an estimated 31 million citizens who are eligible to vote in the 2019 Indonesian general election. It is Indonesia’s second largest province measured in terms of its population. East Java is generally considered a stronghold of Jokowi. This is because he won handily against Prabowo in the province – with a margin of six percent – during the pair’s first presidential match-up in 2014. Most experts expect Jokowi to have a strong advantage in East Java because of the dominance of two political parties within the president’s coalition, the Indonesian Democratic Party Struggle (PDIP) − which traces its lineage to Indonesia’s founding president Sukarno, and the National Awakening Party (PKB) − which is affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation. -

Western Java, Indonesia)

Religious Specificities in the Early Sultanate of Banten (Western Java, Indonesia) Gabriel Facal Université de Provence, Marseille. Abstrak Artikel ini membahas kekhasan agama di Banten pada masa awal Islamisasi di wilayah tersebut. Karakteristik utama dari proses Islamisasi Banten terletak pada hubungan antara perdagangan dengan jaringan Muslim, kosmopolitanisme yang kuat, keragaman praktek keislaman, besarnya pengikut persaudaraan dan maraknya praktik esotoris. Kekhasan ini menunjukkan bahwa proses Islamisasi Banten sangat cepat dari sisi waktu dan perpindahan agama/konversi yang terjadi merupakan hasil dari proses saling mempengaruhi antara Islam, agama lokal, dan kosmologi. Akibatnya, muncul anggapan bahwa Banten merupakan benteng ortodoksi agama. Kesan yang muncul saat ini adalah bahwa Banten sebagai basis gerakan rigoris/radikal dipengaruhi oleh bentuk-bentuk keislaman yang tumbuh dalam sejarah. Dominasi pandangan media juga menampik kenyataan bahwa persandingan antara agama dan ritual masih membentuk struktur kekuasaan. Artikel ini bertujuan untuk berkontribusi dalam diskusi akademik terkait fenomena tersebut. Abstract The author examines the religious specifics of Banten during the early Islamizing of the region. The main characteristics of the process resided in a link between commerce and Muslim networks, a strong cosmopolitism, a variety of the Islam practices, the large number of brotherhood followers and the popularity of esoteric practices. These specificities indicated that the Islamizing of the region was very progressive within 16th century and the processes of conversion also generated inter-influence with local religious practices and cosmologies. As a consequence, the widespread assertion that Banten is a bastion of religious orthodoxy and the image the region suffers today as hosting bases of rigorist movements may be nuanced by the variety of the forms that Islam 91 Religious Specificities in the Early Sultanate of Banten (Western Java, Indonesia) took throughout history. -

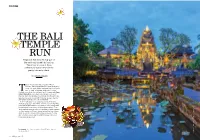

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Demographic Changes in Indonesia and the Demand for a New Social Policy

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository Journal of Policy Science Vol.5 Demographic Changes in Indonesia and the Demand for a New Social Policy Nazamuddin ※ Abstract This article describes the demographic changes and their social and economic implications and challenges that will confront Indonesia in the future. I calculate trends in the proportion of old age population and review the relevant literature to make some observations about the implications of such changes. The conclusions I make are important for further conceptual elaboration and empirical analysis. Based on the population data and projections from the Indonesian Central Agency of Statistics, National Planning Agency, other relevant sources, I find that Indonesia is now entering the important phase of demographic transition in which a window of opportunity prevails and where saving rate can be increased. I conclude that it is now time for Indonesia to prepare a new social policy in the form of overall welfare provision that should include healthcare and pension for every Indonesian citizen. Key words : demographic changes; social security; new social policy 1. Introduction Demographic change, mainly characterized by a decreasing long-term trend in the proportion of productive aged population and increasing proportion of aging population, is becoming increasingly more important in public decision making. A continuing fall in the birth and mortality rates changes the age structure of the population. Its effects are wide-ranging, from changes in national saving rates and current account balances, as seen in major advanced countries (Kim and Lee, 2008) to a shift from land-based production and stagnant standards of living to sustained income growth as birth rates become low (Bar and Leukhina, 2010). -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang. -

Indonesian Schools: Shaping the Future of Islam and Democracy in a Democratic Muslim Country

Journal of International Education and Leadership Volume 5 Issue 1 Spring 2015 http://www.jielusa.org/ ISSN: 2161-7252 Indonesian Schools: Shaping the Future of Islam and Democracy in a Democratic Muslim Country Kathleen E. Woodward University of North Georgia This paper examines the role of schools in slowly Islamizing Indonesian society and politics. Why is this Islamization happening and what does it portend for the future of democracy in Indonesia? The research is mostly qualitative and done through field experience, interviews, and data collection. It is concluded that radical madrasahs are not the main generators of Islamization, but instead the widespread prevalence of moderate Islamic schools are Islamizing Indonesian society and politics. The government began the “mainstreaming” of Islamic elementary and secondary schools, most of which are private, in 1975. This has continued and grown, making them popular options for education today. The government has more recently been increasing the role of state run Islamic universities by expanding their degree offerings to include many non- Islamic disciplines. The use of Islamic schools to educate Indonesians is due to the lack of development of secular public schools and high informal fees charged for the public schools. By making Islamic schools an attractive option that prepares students for success, society has been Islamized slowly as the number of alumni increases and as these alumni play leadership roles in society, business, and government. This Islamization is not of a radical nature, but it is resulting in more Islamic focused public discourse and governing policy, and low levels of tolerance for other faiths and variant Muslim practices. -

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra. -

The Rise of Islamic Religious-Political

Hamid Fahmy Zarkasyi THE RISE OF ISLAMIC RELIGIOUS-POLITICAL MOVEMENTS IN INDONESIA The Background, Present Situation and Future1 Hamid Fahmy Zarkasyi The Institute for Islamic Studies of Darussalam, Gontor Ponorogo, Indonesia Abstract: This paper traces the roots of the emergence of Islamic religious and political movements in Indonesia especially during and after their depoliticization during the New Order regime. There were two important impacts of the depoliticization, first, the emergence of various study groups and student organizations in university campuses. Second, the emergence of Islamic political parties after the fall of Suharto. In addition, political freedom after long oppression also helped create religious groups both radical on the one hand and liberal on the other. These radical and liberal groups were not only intellectual movements but also social and political in nature. Although the present confrontation between liberal and moderate Muslims could lead to serious conflict in the future, and would put the democratic atmosphere at risk, the role of the majority of the moderates remains decisive in determining the course of Islam and politics in Indonesia. Keywords: Islamic religious-political movement, liberal Islam, non-liberal Indonesian Muslims. Introduction The rise of Islamic political parties and Islamic religious movements after the fall of Suharto was not abrupt in manner. The process was gradual, involving numbers of national and global factors. 1 The earlier version of this paper was presented at the conference “Islam and Asia: Revisiting the Socio-Political Dimension of Islam,” jointly organized by Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA) and Institute of Islamic Understanding Malaysia (IKIM), 15-16 October, Tokyo.