Valuing Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?

Fordham Law Review Volume 86 Issue 6 Article 12 2018 Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete? Kevin Brown Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Brown, Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 2773 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss6/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTION OF THE RACIAL IDENTITY OF CHILDREN OF LOVING: HAS OUR THINKING ABOUT RACE AND RACIAL ISSUES BECOME OBSOLETE? Kevin Brown* It is a special honor for me to have this opportunity to discuss the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Loving v. Virginia1 at a Symposium held in honor of its fiftieth anniversary. I served on the panel entitled “The Children of Loving,”2 which for me has two connotations. First, as an African American who married a white woman twenty years after the decision, I am a child of Loving in the sense that I was in an interracial marriage. But as a father of two black-white biracial children, I am also a father of two Loving children. -

Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology Versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 21:31 Atlantis Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice Études critiques sur le genre, la culture, et la justice Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta Volume 39, numéro 2, 2018 Résumé de l'article This article explores how race and gender become distinguished from each URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064075ar other in contemporary scholarly and activist debates on the comparison DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar between transracialism and transgender identities. The article argues that transracial-transgender distinctions often reinforce divides between Aller au sommaire du numéro autological (self-determined) and genealogical (inherited) aspects of subjectivity and obscure the constitution of this division through modern technologies of power. Éditeur(s) Mount Saint Vincent University ISSN 1715-0698 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dutta, A. (2018). Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism. Atlantis, 39(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar All Rights Reserved © Mount Saint Vincent University, 2018 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Special Section: Research Allegories ofGender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta is an Assistant Professor in the de- Introduction: Two Scenes ofTransgender partments of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies Recognition and Asian and Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Iowa. -

TDS-MAP58: Identidades Mal Entendidas. Raza Y Clase En El

traficantes de sueños Traficantes de Sueños no es una casa editorial, ni si- quiera una editorial independiente que contempla la publicación de una colección variable de textos crí- ticos. Es, por el contrario, un proyecto, en el sentido estricto de «apuesta», que se dirige a cartografiar las líneas constituyentes de otras formas de vida. La cons- trucción teórica y práctica de la caja de herramientas que, con palabras propias, puede componer el ciclo de luchas de las próximas décadas. Sin complacencias con la arcaica sacralidad del libro, sin concesiones con el narcisismo literario, sin lealtad alguna a los usurpadores del saber, TdS adopta sin ambages la libertad de acceso al conocimiento. Queda, por tanto, permitida y abierta la reproducción total o parcial de los textos publicados, en cualquier formato imaginable, salvo por explícita voluntad del autor o de la autora y sólo en el caso de las ediciones con ánimo de lucro. Omnia sunt communia! mapas 58 Mapas. Cartas para orientarse en la geografía variable de la nueva composición del trabajo, de la movilidad entre fron- teras, de las transformaciones urbanas. Mutaciones veloces que exigen la introducción de líneas de fuerza a través de las discusiones de mayor potencia en el horizonte global. Mapas recoge y traduce algunos ensayos, que con lucidez y una gran fuerza expresiva han sabido reconocer las posibili- dades políticas contenidas en el relieve sinuoso y controver- tido de los nuevos planos de la existencia. © 2018, Asad Haider © 2020, de esta edición, Traficantes de Sueños creative cc commons Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivadas 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Usted es libre de: * Compartir - copiar, distribuir, ejecutar y comunicar públicamente la obra Bajo las condiciones siguientes: * Reconocimiento — Debe reconocer los créditos de la obra de la manera especificada por el autor o el licenciante (pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene su apoyo o que apoyan el uso que hace de su obra). -

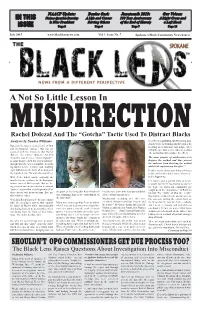

Rachel Dolezal and the “Gotcha” Tactic Used to Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams Be Defined As Pointing out the Wrong Way

NAACP Update: Denise Osei: Juneteenth 2015: Our Voices: IN THIS Naima Quarles-Burnley A Life and Career 150 Year Anniversary A Right Cross and is New President Serving Others of the End of Slavery a Left Hook ISSUE Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 13 July 2015 www.blacklensnews.com Vol. 1 Issue No. 7 Spokane’s Black Community News Source A Not So Little Lesson In MISDIRECTIONRachel Dolezal And The “Gotcha” Tactic Used To Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams be defined as pointing out the wrong way. Another way of defining misdirection is by Based on the unprecedented level of fury focusing on its function. Any magic effect and international “outrage” that was as- (what the spectator sees) requires a method sociated with the discovery that Rachel (the method used to produce the effect). Dolezal, the former Spokane NAACP President, was in fact a “white imposter”, The main purpose of misdirection is to as some people called her, you would have disguise the method and thus prevent thought that she was responsible for pull- the audience from detecting the method ing out her service revolver and emptying whilst still experiencing the effect.” eight bullets into the back of an unarmed, In other words, doing something to distract fleeing black man. No wait, that wasn’t her. people so that they don’t notice what is ac- Well, if she didn’t murder anybody, she tually happening. must be the one to blame for the dispropor- If it wasn’t such a painful thing to watch, tionate rates of Black people that are be- it would have been fascinating to observe ing arrested and incarcerated in a criminal the degree to which our community got “justice” system that actually profits off of caught up in the “importance” of Rachel’s the point of declaring that Rachel Dolezal I had no idea at the time how profound that those arrests and incarcerations. -

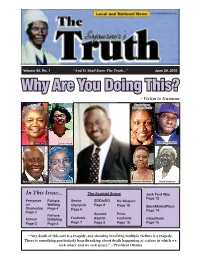

Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman

Volume 34, No. 1 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” June 24, 2015 Why Are You Doing This? - Victim to Gunman Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor Ethel Lance Cynthia Hurd Tywanza Sanders Rev. Daniel Simmons Myra Thompson Rev. Clementa Pinckney Sharonda Singleton Susie Jackson In This Issue... The Soulcial Scene Jack Ford Way Page 12 Perryman Fathers Senior ZOOtoDO No Weapon on Walking Olympics Page 8 Page 10 BlackMarketPlace Charleston Page 4 Page 6 Page 14 Page 2 Fathers Second Price Tolliver Dribbling Festivals Baptist Fashions Classifieds Page 3 Page 5 Page 7 Page 9 Page 16 Page 15 “Any death of this sort is a tragedy, any shooting involving multiple victims is a tragedy. There is something particularly heartbreaking about death happening at a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace.” - President Obama Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth June 24, 2015 Jesus and Violence Dr. Donald L. Perryman – By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, D.Min. The Truth Contributor Father to his Daughters, ...The tensions which we witness in the world Father to the Community today are indicative of the fact that a new By Tracee Perryman Guest Column world is being born and an old world is pass- Dr. Donald L. Perryman has been a mentor ing away. and father-figure to so many in the church, -- Martin Luther King, Jr. in “The Birth of a New Age” and in the community. Today, I want to focus on the father he was at home. Father/daugh- ter relationships are very complex. Fathers The Christian commands to “Love your en- parent very differently from mothers. -

Racial Transitions and Controversial Positions: Reply to Taylor, Gordon, Sealey, Hom, and Botts

DOI: 10.5840/philtoday2018223200 Racial Transitions and Controversial Positions: Reply to Taylor, Gordon, Sealey, Hom, and Botts REBECCA TUVEL Abstract: In this essay, I reply to critiques of my article “In Defense of Transracialism.” Echoing Chloë Taylor and Lewis Gordon’s remarks on the controversy over my article, I first reflect on the lack of intellectual generosity displayed in response to my paper. In reply to Kris Sealey, I next argue that it is dangerous to hinge the moral acceptability of a particular identity or practice on what she calls a collective co-signing. In reply to Sabrina Hom, I suggest that relying on the language of passing to describe transracial- ism is potentially misleading. In reply to Tina Botts, I both defend analytic philosophy of race against her multiple criticisms and suggest that Botts’s remarks risk complicity with a form of transphobia that Talia Mae Bettcher calls the Basic Denial of Authenticity. I end by gesturing toward a more inclusive understanding of racial identity. Key words: transracialism, transracial, transgender, passing, racial essentialism, Rachel Dolezal y article “In Defense of Transracialism” argues that considerations in rightful support of transgender identity extend to transracial Midentity. The impetus for my article was the 2015 controversy over Rachel Dolezal—the former NAACP chapter head who self-identifies as black despite having white parents. My argument sought to name and challenge an underlying transphobic and racially essentialist logic at work in public discus- sions of Dolezal’s story. In my research on this topic, I found that preexisting philosophical literature failed to consider adequately the metaphysical and ethical possibility of transracialism. -

Amended Complaint

Case 1:17-cv-05427-ALC Document 37-1 Filed 08/30/17 Page 1 of 73 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.; THE ORDINARY PEOPLE SOCIETY; #HEALSTL; NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE PENNSYLVANIA Civil Action No. 17 Civ. 05427 (ALC) STATE CONFERENCE; NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT PEOPLE FLORIDA STATE CONFERENCE; HISPANIC FEDERATION; MI FAMILIA VOTA; SOUTHWEST VOTER REGISTRATION EDUCATION PROJECT; and LABOR COUNCIL FOR LATIN AMERICAN ADVANCEMENT, Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States; PRESIDENTIAL ADVISORY COMMISSION ON ELECTION INTEGRITY, an advisory committee commissioned by President Trump; MICHAEL R. PENCE, in his official capacity as Chair of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity; and KRIS W. KOBACH, in his official capacity as Vice Chair of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, Defendants. 1 Case 1:17-cv-05427-ALC Document 37-1 Filed 08/30/17 Page 2 of 73 FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT PRELIMINARY STATEMENT The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., The Ordinary People Society, #HealSTL; the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (“NAACP”) Pennsylvania State Conference; the NAACP Florida State Conference; Mi Familia Vota; the Hispanic Federation; Southwest Voter Registration Education Project; and the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement(“Plaintiffs”) bring this action against Donald J. Trump, in his official capacity as President of the United States (“President Trump”), the Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity (“Commission”), Michael R. Pence, in his official capacity as Vice President of the United States and chair of the Commission (“Vice President Pence”), and Kris W. -

2019-2020 CURRICULUM VITA KEVIN COKLEY, Ph.D. UT System

Curriculum Vita of Kevin Cokley Page 1 Academic Year: 2019-2020 CURRICULUM VITA KEVIN COKLEY, Ph.D. UT System Academy of Distinguished Teachers Fellow University of Texas at Austin Distinguished Teaching Professor Oscar and Anne Mauzy Regents Professorship for Educational Research and Development Department of African and African Diaspora Studies Department of Educational Psychology University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX 78712 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kevincokley.com EDUCATION Ph.D. Georgia State University 1993-1998 Department of Counseling and Psychological Services M.Ed. University of North Carolina at Greensboro 1991-1993 Department of Counselor Education B.A. Wake Forest University 1987 –1991 Department of Psychology PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS University of Texas at Austin 2014 – Director, Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis IUPRA accomplishments during my directorship include: Ø Secured two $60,000 grants from Georgetown Health Foundation Ø Developed State of Black Lives in Texas Initiative Ø Created public opinion poll among registered Texas voters Ø Produced 35 Research Reports and 53 Op-Eds with 90 by-lines Ø Mentioned in the press 37 times with 40 by-lines Ø Held series of public events on topics including charter schools, free speech, and criminal justice reform Ø Conducted research that led to creation of UT Hate Incident Policy University of Texas at Austin 2013- Professor of African and African Diaspora Studies Curriculum Vita of Kevin Cokley Page 2 Professor of Counseling Psychology Interim -

Transcript: Why Are White American Women Posting As Black and Latinx Women?

The Table Podcast (Jan.-Mar. 2021) Item Type Recording, oral Authors Carney, Courtney Jones; Ferreira, Rosemary Publication Date 2021 Keywords current events; University of Maryland, Baltimore. Intercultural Center; Culture; Ethnicity; Race; University of Maryland, Baltimore Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 03/10/2021 04:34:24 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/14810 Transcript: Why Are White American Women Posting as Black and Latinx Women? Producer, Angela Jackson: Warning, in this episode there are mentions of police violence and substance abuse. Please exercise caution for all listeners under thirteen. Courtney Jones Carney Do you remember back in September 2020 when there was all this news about an associate professor at George Washington University who was pretending to be an Afro-Latina from the Bronx? Rosemary Ferreira I do remember that. The professor’s name is Jessica Krug and she was a professor in history and Africana studies. She released a public letter in which she apologized for being a quote, “cultural leech” and a quote, “coward” for lying about her race and ethnicity, because in truth she is a white Jewish woman from suburban Kansas. Courtney Jones Carney So what’s really interesting here is that Krug has built her career as an academic studying African and Caribbean cultures and she’s claimed activist fighting against gentrification and police brutality in New York City. Archived Recording (Jessica Krug) It’s all part of copwatching and all part of the culture. And I realize now that I’m talking about this a little bit institutionally. -

Rachel Dolezal: an Intersectional Analysis

Article Rachel Dolezal: An Intersectional Analysis By Brittney McIntyre Abstract This paper uses intersectionality theory and identity politics to analyze the transracialism of Rachel Dolezal. I establish the social construction of racial identity, and the basis of all identity construction in white supremacist settler colonial logics. Using concepts of essentialism and identity politics, I then investigate the ways in which individuals define and perform racial identity. I include analyses on how Dolezal performs transracial identity, and the implications her actions have on social definitions and meanings of blackness. I then expand on Dolezal’s appropriation of blackness and her conflation of physical appearance with cultural and historical identity. I discuss Dolezal’s fixation as a means to cope with childhood trauma and, using this trauma as a point of departure, briefly examine the intergenerational passing of trauma, implicating Dolezal in the erasure of the voices and experiences of black women. I provide a brief discussion on colorism and privilege before moving to a comparison of transracial and transgender identities. Finally, I engage the power of social constructions and use de- colonial frameworks to assert that, while the concept of transracialism is not inherently at issue in the abstract, Dolezal’s misunderstanding of racial identity in contextual and practical application creates tensions and challenges that are, in fact, quite problematic. Author’s Note The term “transracial” has been used in academic, creative, and cultural writing as a signifier denoting people adopted across race, often across countries or continents, and sometimes without fully formed consent. It also describes a type of family unit and a form of parenting. -

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and the Fear of Indigenous (Dis)Order: New Medico-Legal Alliances for Capturing and Managing Indigenous Life in Canada

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and the Fear of Indigenous (dis)Order: New Medico-Legal Alliances for Capturing and Managing Indigenous Life in Canada Leslie Sabiston Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Leslie Sabiston All Rights Reserved Abstract Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and the Fear of Indigenous (dis)Order: New Medico-Legal Alliances for Capturing and Managing Indigenous Life in Canada Leslie Sabiston While accounting for less than 5 percent of the Canadian population, Indigenous peoples represent more than 30 percent of the federal prison population of Canada. In a prairie province like Manitoba the numbers are even more extreme, with over three-quarters of the prison population being Indigenous. This contemporary “Indian Problem” has been theorized in recent decades as an outcome of the colonial history of Canada. Indigenous Studies scholarship has critiqued the temporal political imaginary of the subsequent reconciliation discourse that locates colonial violence, and, thus, culpability and responsibility of the Canadian state, to an ‘event’ of history. Such national stories not only diminish the interrogation of ongoing structures of colonial violence but relegate any meaningful political processes of accountability and justice to the dustbin of history. This ‘legacy’ framework of historicizing colonial violence has created fecund conditions for (re)apprehending Indigenous bodies at the junctures of legal and medical reasoning, where questions of punishment, containment and rehabilitation for criminal actions become uneasily blurred with questions of healing and repair of damaged bodies and minds. -

Rachel Dolezal, Caitlyn Jenner, and Identity Transformation: Identity Legitimization in Internet Comments Sarah G

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Communication Studies Student Scholarship Communication Studies 2016 Rachel Dolezal, Caitlyn Jenner, and Identity Transformation: Identity Legitimization in Internet Comments Sarah G. Pillow Hollins University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/commstudents Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pillow, Sarah G., "Rachel Dolezal, Caitlyn Jenner, and Identity Transformation: Identity Legitimization in Internet Comments" (2016). Communication Studies Student Scholarship. 1. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/commstudents/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 Rachel Dolezal, Caitlyn Jenner, and Identity Transformation: Identity Legitimization in Internet Comments Sarah G. Pillow Hollins University 2 Abstract This paper looks at the ways in which a person's identity may be legitimized or delegitimized by looking at the supposed identity transformations of Rachel Dolezal and Caitlyn Jenner, and the subsequent internet reactions. Through analyzing the article, this paper considers the citizen critic and their role in creating an identity through five criteria of legitimization: 1. Identity has evidence to back it up 2. Perceived truthfulness of the Person 3. Permanence of Identity 4. Experience of Oppression 5. Activism and/or Advocacy 3 In the summer of 2015, with the discussion of identity based conversations, such as the stories of Caitlyn Jenner and Rachel Dolezal, brought back the larger discussion on identity politics.