Chalcolithic and Bronze Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026

North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 North Highland Forest District North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016 - 2026 Plan Reference No:030/516/402 Plan Approval Date:__________ Plan Expiry Date:____________ | North Sutherland LMP | NHFD Planning | North Sutherland Land Management Plan 2016-2026 Contents 4.0 Analysis and Concept 4.1 Analysis of opportunities I. Background information 4.2 Concept Development 4.3 Analysis and concept table 1.0 Introduction: Map(s) 4 - Analysis and concept map 4.4. Land Management Plan brief 1.1 Setting and context 1.2 History of the plan II. Land Management Plan Proposals Map 1 - Location and context map Map 2 - Key features – Forest and water map 5.0. Summary of proposals Map 3 - Key features – Environment map 2.0 Analysis of previous plan 5.1 Forest stand management 5.1.1 Clear felling 3.0 Background information 5.1.2 Thinning 3.1 Physical site factors 5.1.3 LISS 3.1.1 Geology Soils and landform 5.1.4 New planting 3.1.2 Water 5.2 Future habitats and species 3.1.2.1 Loch Shin 5.3 Restructuring 3.1.2.2 Flood risk 5.3.1 Peatland restoration 3.1.2.3 Loch Beannach Drinking Water Protected Area (DWPA) 5.4 Management of open land 3.1.3 Climate 5.5 Deer management 3.2 Biodiversity and Heritage Features 6.0. Detailed proposals 3.2.1 Designated sites 3.2.2 Cultural heritage 6.1 CSM6 Form(s) 3.3 The existing forest: 6.2 Coupe summary 3.3.1 Age structure, species and yield class Map(s) 5 – Management coupes (felling) maps 3.3.2 Site Capability Map(s) 6 – Future habitat maps 3.3.3 Access Map(s) 7 – Planned -

Offers Over £195,000 the Dovecote, 11 Swordale Steading, Evanton

Bedroom 3 ENTRY 3.89m x 2.76m approx By mutual agreement. Window facing west with wooden venetian blind. Good sized double room with radiator. VIEWING Contact Anderson Shaw & Gilbert Property Department on 01463 253911 to Bathroom arrange an appointment to view. 1.97m x 2.87m approx E-MAIL Opaque glazed window facing east with wooden venetian blind. White three [email protected] piece suite comprising of WC, wash hand basin and bath. Ceramic tiling to splash-back above the wash hand basin and to picture rail height surrounding HSPC the bath. Mira electric shower over the bath and fitted shower curtain rail. 56351 Wall mounted mirror above the wash hand basin. Vinyl flooring. GARDEN There is a large gravelled driveway providing excellent off-road parking facilities with the potential for a garage/garden shed and to be fully enclosed to create extended garden and driveway. An access ramp leads through a wooden gate with further parking. There is a grassed area which extends from the east side of the property and is fully enclosed by fencing. There is a raised gravelled area creating an area for seating and al-fresco dining. Rotary clothes dryer. HEATING The property benefits from an oil fired Combi boiler that manages the central heating and hot water system GLAZING The subjects are double glazed. EXTRAS The Dovecote, 11 Swordale All fitted floor coverings, curtain rails, coat hooks & integral kitchen appliances are included in the asking price. Steading, Evanton, IV16 9XA OPTIONAL EXTRAS Window blinds, curtains and pendent lampshades, Bosch dishwasher, Hoover washing machine, Whirlpool tumble dryer and Zanussi fridge/freezer are available to purchase along with some of the furniture. -

The Wisbech Standard 26/06/11 Fenland District Archaeological

The Wisbech Standard 26/06/11 Fenland District Archaeological Planning - A Response to Councillor Melton We the undersigned consider to be shocking and potentially disastrous the recent declaration by Councillor Alan Melton (reported in the Cambs Times and Wisbech Standard) that, as of July 1st, the Fenland District Council will no longer apply archaeological planning condition. His speech to the Fenland Council Building and Design Awards ceremony at Wisbech noted the safeguarding of natural and aesthetic concerns, but made no mention of heritage aside from: “in local known historical areas, such as next to a 1000 year old church…. Common sense will prevail! The bunny huggers won't like this, but if they wish to inspect a site, they can do it when the footings are being dug out”. If Fenland District Council proceed with these plans, not only will it find itself contravening national planning guidelines and existing cultural and heritage statute and case law, it is likely any development will be open to legal challenges that will involve the Council (and by extension its rate-payers) in major financial costs and cause prospective developers serious delays, if not worse. All these factors run counter to Councillor Melton’s arguments and he will place Fenland District Council at a considerable financial risk. Rather than, as claimed, being an impediment to local development, development-related archaeology is a highly professional field and the vast majority of such excavations within England occur without any delay or redesign consequences to subsequent building programmes. Indeed, not only is archaeological fieldwork a source of graduate employment, but also now significantly contributes to the local rural economy (plant hire, tourism etc.). -

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Northumberland Rocks!

PAST Peebles Archaeological Society Times September 2012 Northumberland rocks! Summer Field Trip 2012 The main traditions are thought to date to Jeff Carter reports on our the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (c summer excursion to visit rock 4,000 to 1,500BC), and are represented by art sites in the Wooler area of cup and ring carvings, and passage grave or Northumberland. megalithic carvings. Intriguingly, some cup and ring carvings have been carefully removed and reused in later burials, but On Sunday 3 June, a group of eleven PAS the reasons for the initial carving and the members travelled down to re-use are not known – yet, or perhaps Northumberland for a day’s exploration of ever. rock art. After a brief visit to the Maelmin Heritage Trail near the village of Milfield Many theories have been put forward, but we called at the local café to rendezvous the location of carvings at significant places with rock art expert Dr Tertia Barnett, in the landscape provides a possible clue. along with two of her students who were Also, recently excavated areas around to join us for the day. rock art in Kilmartin glen provide evidence for cobbled viewing points and also the Dr Barnett is an Honorary Fellow in incorporation of quartz fragments archaeology at Edinburgh University, and is (possibly from the hammer stones used to well known to the PAS members involved create the carvings) set into clay in cracks in our Kilrubie survey as she managed the in the rock. This suggests the creation of RCAHMS Scotland’s Rural Past project of the art, or perhaps the re-carving over which it formed a part. -

NEWSLETTER October 2015

NEWSLETTER October 2015 Dates for your diary MAD evenings Tuesdays 7.30 - 9.30 pm at Strathpeffer Community Centre 17th November Northern Picts - Candy Hatherley of Aberdeen University 8th December A pot pourri of NOSAS activity 19th January 2016 Rock Art – Phase 2 John Wombell 16th February 15th March Bobbin Mills - Joanna Gilliat Winter walks Thursday 5th November Pictish Easter Ross with soup and sandwiches in Balintore - David Findlay Friday 4th December Slochd to Sluggan Bridge: military roads and other sites with afternoon tea - Meryl Marshall Saturday 9th January 2016 Roland Spencer-Jones Thursday 4th February Caledonian canal and Craig Phadrig Fort- Bob & Rosemary Jones Saturday 5th March Sat 9th April Brochs around Brora - Anne Coombs Training Sunday 8 November 2 - 4 pm at Tarradale House Pottery identification course (beginners repeated) - Eric Grant 1 Archaeology Scotland Summer School, May 2015 The Archaeology Scotland Summer School for 2015 covered Kilmartin and North Knapdale. The group stayed in Inveraray and included a number of NOSAS members who enjoyed the usual well researched sites and excellent evening talks. The first site was a Neolithic chambered cairn in Crarae Gardens. This cairn was excavated in the 1950s when it was discovered to contain inhumations and cremation burials. The chamber is divided into three sections by two septal slabs with the largest section at the rear. The next site was Arichonan township which overlooks Caol Scotnish, an inlet of Loch Sween, and which was cleared in 1848 though there were still some households listed in the 1851 census. Chambered cairn Marion Ruscoe Later maps indicate some roofed buildings as late as 1898. -

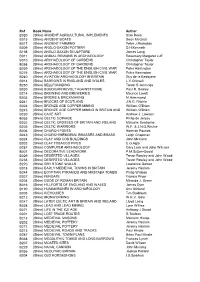

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Bronze Objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13Th-8Th Century BC) Pierre-Yves Milcent

Bronze objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13th-8th century BC) Pierre-Yves Milcent To cite this version: Pierre-Yves Milcent. Bronze objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13th-8th century BC). Hunter Fraser; Ralston Ian. Scotland in Later Prehistoric Europe, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, pp.19-46, 2015, 978-1-90833-206-6. hal-01979057 HAL Id: hal-01979057 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01979057 Submitted on 12 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. FROM CHAINS TO BROOCHES Scotland in Later Prehistoric Europe Edited by FRASER HUNTER and IAN RALSTON iii SCOTLAND IN LATER PREHISTORIC EUROPE Jacket photography by Neil Mclean; © Trustees of National Museums Scotland Published in 2015 in Great Britain by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Society of Antiquaries of Scotland National Museum of Scotland Chambers Street Edinburgh EH1 1JF Tel: 0131 247 4115 Fax: 0131 247 4163 Email: [email protected] Website: www.socantscot.org The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland is a registered Scottish charity No SC010440. ISBN 978 1 90833 206 6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA)

Eupedia Home > Genetics > Haplogroups (home) > Haplogroup R1b Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA) Content 1. Geographic distribution Author: Maciamo. Original article posted on Eupedia. 2. Subclades Last update January 2014 (revised history, added lactase 3. Origins & History persistence, pigmentation and mtDNA correspondence) Paleolithic origins Neolithic cattle herders The Pontic-Caspian Steppe & the Indo-Europeans The Maykop culture, the R1b link to the steppe ? R1b migration map The Siberian & Central Asian branch The European & Middle Eastern branch The conquest of "Old Europe" The conquest of Western Europe IE invasion vs acculturation The Atlantic Celtic branch (L21) The Gascon-Iberian branch (DF27) The Italo-Celtic branch (S28/U152) The Germanic branch (S21/U106) How did R1b become dominant ? The Balkanic & Anatolian branch (L23) The upheavals ca 1200 BCE The Levantine & African branch (V88) Other migrations of R1b 4. Lactase persistence and R1b cattle pastoralists 5. R1 populations & light pigmentation 6. MtDNA correspondence 7. Famous R1b individuals Geographic distribution Distribution of haplogroup R1b in Europe 1/22 R1b is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, reaching over 80% of the population in Ireland, the Scottish Highlands, western Wales, the Atlantic fringe of France, the Basque country and Catalonia. It is also common in Anatolia and around the Caucasus, in parts of Russia and in Central and South Asia. Besides the Atlantic and North Sea coast of Europe, hotspots include the Po valley in north-central Italy (over 70%), Armenia (35%), the Bashkirs of the Urals region of Russia (50%), Turkmenistan (over 35%), the Hazara people of Afghanistan (35%), the Uyghurs of North-West China (20%) and the Newars of Nepal (11%). -

Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-Eòlais Na Gàidhealtachd

Events guide Iùl thachartasan Highland Archaeology Festival Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 29th Sept -19th Oct2018 Celebrating Archaeology,Historyand Heritage A’ Comharrachadh Arc-eòlas,Eachdraidh is Dualchas Archaeology Courses The University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute Access, degree, masters and postgraduate research available at the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute. www.uhi.ac.uk/en/archaeology-institute/ Tel: 01856 569225 Welcome to Highland Archaeology Festival 2018 Fàilte gu Fèis Arc-eòlais na Gàidhealtachd 2018 I am pleased to introduce the programme for this year’s Highland Archaeology Festival which showcases all of Highland’s historic environment from buried archaeological remains to canals, cathedrals and more. The popularity of our annual Highland Archaeology Festival goes on from strength to strength. We aim to celebrate our shared history, heritage and archaeology and showcase the incredible heritage on our doorsteps as well as the importance of protecting this for future generations. The educational and economic benefits that this can bring to communities cannot be overstated. New research is being carried out daily by both local groups and universities as well as in advance of construction. Highland Council is committed to letting everyone have access to the results of this work, either through our Historic Environment Record (HER) website or through our programme of events for the festival. Our keynote talks this year provide a great illustration of the significance of Highland research to the wider, national picture. These lectures, held at the council chamber in Inverness, will cover the prehistoric period, the early medieval and the industrial archaeology of more recent times. -

Falls of Shin Visitor Centre, Achany, Lairg, IV27 4EE

The Highland Licensing Board Agenda 8.3 Item Meeting – 2 August 2017 Report HLB/089/17 No Application for the grant of a provisional premises licence under the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005 Falls of Shin Visitor Centre, Achany, Lairg, IV27 4EE Report by the Clerk to the Licensing Board Summary This report relates to an application for the provisional grant of a premises licence in respect of Falls of Shin Visitor Centre, Achany, Lairg. 1.0 Description of premises 1.1 Falls of Shin Visitor Centre is a 60 seat café with gift shop. 2.0 Operating hours 2.1 The applicant seeks the following on-sales and off-sales hours: On sales: Monday to Sunday: 1100 hrs to 2200 hrs Off-sales: Monday to Sunday 1000 hrs to 2200 hrs 3.0 Background 3.1 On 13 June 2017 the Licensing Board received an application for the grant of a provisional premises licence from Kyle of Sutherland Development Trust. 3.2 The application was accompanied by the necessary Section 50 certification in terms of Planning, Building Standards and Food Hygiene. 3.3 The application was publicised during the period 22 June until 13 July 2017 and confirmation that the site notice was displayed has been received. 3.4 In accordance with standard procedure, Police Scotland, the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service and the Council’s Community Services (Environmental Health) and Planning and Building Standards were consulted on the application. 3.5 Notification of the application was also sent to NHS Highland and the local Community Council. 3.6 Further to this publication and consultation process, no timeous objections or representations have been received. -

Highland Heritage Archaeological Consultancy

Highland Heritage Archaeological Consultancy Professional Archaeological & Heritage Advice Toad Hall Studios Desk-based Assessment & Evaluation Bhlaraidh House Field Survey & Watching Briefs Glenmoriston Database & GIS design Inverness-shire IV63 7YH Archaeological Survey & Photographic Recording at Fearn Free Church, Planning Application SU-08-412 Highland Council Archaeology Unit brief 31 October 2008, Aspire Project UID HH 2009/01 for Mr Stuart Sinclair c/o Reynolds Architecture ltd 1 Tulloch Street Dingwall Highland Heritage is run by Dr Harry Robinson BA MA PhD MIFA FSA Scot. Tel: 01320 351272 email [email protected] Standard Building Survey at Fearn Free Church, Fearn, prior to alteration and change of use of church to form family house with annex Planning Application SU-08-412 as detailed in a brief by Highland Council Archaeology Unit (HCAU) 31 October 2008, Aspire Project UID HH 2009/01 Dr Harry Robinson MIFA, Highland Heritage Archaeological Consultants Contents Summary and recommendations preface Background 1 Location map of development site 2 Site plan 3 Site location 4 Objectives of the survey Desk-based Assessment The architect John Pond Macdonald 5 Biographical details from The Dictionary of Scottish Architects DSA DSA Building Report for Fearn Free Church and Manse 6 Chronological Gazetteer of church buildings by John Pond Macdonald 7 Gazetteer Bibliography 8 Photographs C1-C5 - other churches by John Pond Macdonald 8a Cartographic evidence 8 map 4 - OS 1872 1:2,500 map 9 map 5 - OS 1904 1:2,500 map The Building Survey