State of Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Forest Audax Events on 23Rd May 2021 Starting from Lymington

New Forest Audax Events on 23rd May 2021 Starting from Lymington. (Open air public space – according to restrictions in force at the time) There will be no arranged refuelling venues as controls. Proof of passage will be by gathering “information controls” as you travel. There are many opportunities for refreshment on the courses but to avoided the risk of crowding specific places it will be up to riders to decide where, and if, to stop. New Forest Excursion – 207km (125miles) This event explores every corner and all of the varied New Forest landscapes. The route visits Burley, the western escarpment of the Forest in the Avon Valley, the edge of the Wiltshire Downs, and Cranborne Chase, before returning through the heart of the Forest across Stoney Cross plain through Lyndhurst and Beaulieu to the Solent coastal nature reserve at Lepe. Then a loop back northwards to Redlynch and Hale before a grand finale down the Ornamental Drives, through Brockenhurst and more coastal fringes to the Arrivee. Entry fee: £5 (+ £3 temporary membership fee, if you are not a member of AUK or CTC) Includes: Route sheet, gpx track, brevet card, and AUK validation fee . Enter via the Audax Uk Website Here: https://audax.uk/event-details?eventId=9013 New Forest Day Out - 107km (66miles) This event explores the centre and west of the New Forest with a turning point at the Braemore near Fordingbridge. Entry fee: £4 (No SAE required for postal entries.) (+ £3 temporary membership fee, if you are not a member of AUK or Cycling UK) Includes: Route sheet, gpx track, brevet card and AUK validation fee. -

Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) Rasa Bukontaite1,2*, Kelly B Miller3 and Johannes Bergsten1

Bukontaite et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2014, 14:5 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/14/5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The utility of CAD in recovering Gondwanan vicariance events and the evolutionary history of Aciliini (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) Rasa Bukontaite1,2*, Kelly B Miller3 and Johannes Bergsten1 Abstract Background: Aciliini presently includes 69 species of medium-sized water beetles distributed on all continents except Antarctica. The pattern of distribution with several genera confined to different continents of the Southern Hemisphere raises the yet untested hypothesis of a Gondwana vicariance origin. The monophyly of Aciliini has been questioned with regard to Eretini, and there are competing hypotheses about the intergeneric relationship in the tribe. This study is the first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis focused on the tribe Aciliini and it is based on eight gene fragments. The aims of the present study are: 1) to test the monophyly of Aciliini and clarify the position of the tribe Eretini and to resolve the relationship among genera within Aciliini, 2) to calibrate the divergence times within Aciliini and test different biogeographical scenarios, and 3) to evaluate the utility of the gene CAD for phylogenetic analysis in Dytiscidae. Results: Our analyses confirm monophyly of Aciliini with Eretini as its sister group. Each of six genera which have multiple species are also supported as monophyletic. The origin of the tribe is firmly based in the Southern Hemisphere with the arrangement of Neotropical and Afrotropical taxa as the most basal clades suggesting a Gondwana vicariance origin. However, the uncertainty as to whether a fossil can be used as a stem-or crowngroup calibration point for Acilius influenced the result: as crowngroup calibration, the 95% HPD interval for the basal nodes included the geological age estimate for the Gondwana break-up, but as a stem group calibration the basal nodes were too young. -

Writes of Spring

On 20 March 2019 we asked people across the UK to capture the arrival of the first official day of spring and help create a crowd-sourced nature diary. More than 400 people did just that from across the four corners of the UK – celebrating this season of colour and the natural world coming to life. The following pages are a selection of the entries curated by the writer Abi Andrews. Introduction n 2018, my spring was spent in a caravan, in a glade in view of Carningli mountain, Itopped by a rocky grey outcrop with purple heathers, confettied below with vivid yellow gorse. The caravan sat within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, in an area that saw an influx of ‘back-to-the-landers’ during the seventies. In it you will find covert, sympathetically built dwellings and cooperative human communities in repurposed farmhouses, lying between woods of bent, blackened oaks, their flamboyant colonies of lichens, and boulders covered with soft and ecstatic mosses. On the moors are strange, stunted Welsh horses, their silhouettes hunched like the simplified animals of Neolithic rock art. Clear spring water gurgles up and silvers everything, running brown through the taps after a heavy rain. At night, owls call to each other. In spring 2019, I was the most attentive to the living world that I have ever been, for the transition of a season. I grew up in suburbia, and moved soon after to a city. Living closer to the land has offered me an anchoring, in noticing the seasons more: the fatigue that comes with winter darkness, the processing of firewood for next year, the harvesting of food — being reminded all the time of the future by preparing for it. -

Trinity College War Memorial Mcmxiv–Mcmxviii

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXIV–MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Hebrews 11: 13 Adamson, William at Trinity June 25 1909; BA 1912. Lieutenant, 16th Lancers, ‘C’ Squadron. Wounded; twice mentioned in despatches. Born Nov 23 1884 at Sunderland, Northumberland. Son of Died April 8 1918 of wounds received in action. Buried at William Adamson of Langham Tower, Sunderland. School: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France. UWL, FWR, CWGC Sherborne. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1904; BA 1907; MA 1911. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancshire Allen, Melville Richard Howell Agnew Regiment, 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April 24 1916. Commemorated at Basra Memorial, Iraq. UWL, FWR, CWGC Born Aug 8 1891 in Barnes, London. Son of Richard William Allen. School: Harrow. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity Addy, James Carlton Oct 1 1910. Aviator’s Certificate Dec 22 1914. Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal Flying Corps. Killed in flying Born Oct 19 1890 at Felkirk, West Riding, Yorkshire. Son of accident March 21 1917. Buried at Bedford Cemetery, Beds. James Jenkin Addy of ‘Carlton’, Holbeck Hill, Scarborough, UWL, FWR, CWGC Yorks. School: Shrewsbury. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1910; BA 1913. Captain, Temporary Major, East Allom, Charles Cedric Gordon Yorkshire Regiment. Military Cross. -

River Avon at Bulford

River Avon at Bulford An Advisory Visit by the Wild Trout Trust June 2013 Contents Introduction Catchment and Fishery Overview Habitat Assessment Recommendations Making It Happen 2 Introduction This report is the output of a Wild Trout Trust visit undertaken on the Hampshire Avon on the Snake Bend Syndicate’s (SBS) water near Bulford, national grid reference (NGR) SU155428 to SU155428. The visit was requested by Mr Geoff Wilcox, who is the syndicate secretary and river keeper. The visit was focussed on assessing the habitat and management of the water for wild trout Salmo trutta. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Mr Wilcox. Throughout the report, normal convention is followed with respect to bank identification i.e. banks are designated Left Bank (LB) or Right Bank (RB) whilst looking downstream. Catchment and Fishery Overview The Hampshire Avon is recognised as one of the most important river habitats in the UK. It supports a diverse range of fish and invertebrates and over 180 different aquatic plant species. The Avon (and its surrounding water meadows) has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Area of Conservation (SAC); however, much of the Avon and its tributaries have been significantly modified for land drainage, agriculture, milling and even navigation. 3 The Avon begins its life as two separate streams known as the Avon West and the Avon East, rising near Devizes and the Vale of Pewsey respectively. The Avon West is designated as a SSSI whilst for reasons unknown, the Avon East is not. -

The Epidemiology and Prevention of Paraquat Poisoning Lesley J

Human Toxicol. (1987), 6, 19-29 The Epidemiology and Prevention of Paraquat Poisoning Lesley J. Onyon and Glyn N. Volans National Poisons Information Service, The Poisons Unit, Guy's Hospira!, London SEl 9RT 1 Jn the UK there was an increase in the annual number of deaths associated with paraquat poisoning between 1966 and 1975. Since that time there has been little change in numbers. 2 High mortality is associated commonly with suicidal intent. Serious accidental poisoning from paraquat has never been frequent in the UK and there have been no deaths reported in children since 1977. 3 The National Poisons Information Service has monitored in detail all reports of paraquat poisoning since 1980. Of the 1074 cases recorded there were 209 deaths. In recent years serious poisoning has been more commonly associated with ingestion of concentrated products by males. Local exposure to paraquat has not resulted in systemic poisoning. 4 International data for paraquat poisoning is incomplete and difficult to compare. There is a scarcity of morbidity data at both international and national levels. Information obtained from Poison Control Centres indicates that paraquat poisoning occurs in many countries but detailed comparisons are hindered by lack of standardised methods of recording. 5 Various measures to prevent paraquat poisoning have been introduced. Their effectiveness has not been studied in detail. Some support is provided by the low incidence of serious accidental paraquat poisoning in the UK, but because of the suicidal nature of paraquat poisoning it is unlikely that current preventative measures will influence the number of deaths occurring each year. -

Cycling & Walking Routes Around the Inn from Our Doorstep. . . Brook To

From our doorstep. Brook to Minstead Village There really is no place quite like the New Forest. With its combination Directly from our doorstep, this varied walk takes you through of ancient woodland, open heathland and livestock roaming freely, it’s a ancient woodland, country lanes and open fields, passing the Rufus Stone, unique landscape that has been home to generations of our family for (said to mark the spot where the King was killed by an arrow shot by more than 200 years. Sir Walter Tyrrell in the year 1100), as well as the final resting place of It’s also known for its hundreds of miles of well maintained gravel tracks, the famous Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. cycle networks and footpaths. So, from our secluded northern corner of the New Forest, we’ve chosen a few of our favourite walks and routes either from our doorstep or a short drive away so you can enjoy the New Forest and all it has to offer, as much as we do. Grid ref Postcode Duration Distance SU 273 141 SO43 7HE 3 hours 7.2 miles (approx.) (11.6 km) Accessibility Easy, gentle walk via country lanes, forest woodland and open fields with a few short uphill and downhill inclines, gates, footbridge and five stiles. Local facilities The Bell Inn, Green Dragon, Trusty Servant and Minstead Village Shop. 1. Grassy bridleway past cottages Facing The Green Dragon public house, follow the road to the left and then turn right and follow the roadside path to Canterton Road. Follow this road past houses to a footbridge over a ford. -

The Herpetofauna of Wiltshire

The Herpetofauna of Wiltshire Gareth Harris, Gemma Harding, Michael Hordley & Sue Sawyer March 2018 Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre and Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group Acknowledgments All maps were produced by WSBRC and contain Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2018. Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre staff and volunteers are thanked for all their support throughout this project, as well as the recorders of Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group and the numerous recorders and professional ecologists who contributed their data. Purgle Linham, previously WSBRC centre manager, in particular, is thanked for her help in producing the maps in this publication, even after commencing a new job with Natural England! Adrian Bicker, of Living Record (livingrecord.net) is thanked for supporting wider recording efforts in Wiltshire. The Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Publications Society are thanked for financially supporting this project. About us Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre (WSBRC), based at Wiltshire Wildlife Trust, is the county’s local environmental records centre and has been operating since 1975. WSBRC gathers, manages and interprets detailed information on wildlife, sites, habitats and geology and makes this available to a wide range of users. This information comes from a considerable variety of sources including published reports, commissioned surveys and data provided by voluntary and other organisations. Much of the species data are collected by volunteer recorders, often through our network of County Recorders and key local and national recording groups. Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group (WARG) Wiltshire Amphibian and Reptile Group (WARG) was established in 2008. It consists of a small group of volunteers who are interested in the conservation of British reptiles and amphibians. -

Scottish Stop and Search Powers Genevieve Lennon*

Searching for change: Scottish stop and search powers Genevieve Lennon* A. INTRODUCTION B. SCOTTISH STOP AND SEARCH POWERS (1) Suspicion-based statutory powers (2) Suspicionless statutory powers (3) Non-statutory powers C. COMPATIBILITY WITH THE ECHR (1) Suspicionless statutory powers (2) Suspicion-based statutory powers (3) Non-statutory powers D. CONCLUSION A. INTRODUCTION In numerous countries, stop and search powers are an open sore upon police-community relations, one which is increasingly being challenged through the courts. In the USA, the discriminatory practices associated with stop and search powers led to the coining of terms such as “driving while black” (more recently joined by “flying while brown”). In 2013, the District Court for the Southern District of New York held, inter alia, that the City of New York was liable for their indifference towards the New York City Police Department’s widespread practice of stop and frisk which violated the fourth and fourteenth amendments of the Constitution.1 In England stop and search practices were a commonly cited factor in the * Chancellor’s Fellow, University of Strathclyde. I am grateful to Dr Claire McDiarmid and Prof Kenneth Norrie for their insights regarding children’s capacity to consent and to the anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments. The usual caveats apply. 1 Floyd et al v the City of New York et al 959 F Supp 5d 540 (2013). 1 Tottenham riots, and a stop, search, and arrest power was the catalyst for the Brixton riots.2 Since 2010, stop and search has come before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in two cases, one from the Netherlands, the other from the UK.3 Other examples can be found across the globe.4 By contrast, until very recently stop and search was a non-issue in Scotland. -

THE USE of DAIRY MANURE COMPOST for SUSTAINABLE MAIZE (Zea Mays L.) PRODUCTION

THE USE OF DAIRY MANURE COMPOST FOR SUSTAINABLE MAIZE (Zea mays L.) PRODUCTION Vânia Cabüs de Toledo Thesis submitted to the University of London in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Wye College University of London September 1996 7 BIBL\ t Lc4oI() Abstract Intensive production systems for maize (Zea mays L.) based on the use of inorganic fertilisers are expensive and unsustainable, as their production is dependent on fossil fuels. Additionally, inorganic fertilisers are unable to maintain soil fertility over the long-term, and are related to environmental problems such as soil erosion and nitrate pollution of the ground water table. Moreover, high cost agrochemicals are either unavailable or too costly for small farmers in tropical countries, where maize is usually grown as a subsistence crop. This research project examined the use of compost derived from dairy manure and cereal straw, renewable resources available on the farm, as an organic fertiliser for a sustainable maize production system. The effects of this compost on soil and plant nutrient content, and on maize and weed growth were studied, examining the various soil-plant interactions. The relevant literature was reviewed, comparing different production systems, and examining aspects of maize production, nutrient recycling and the effects and interactions of compost in the soil-plant system. Field and glasshouse experiments were carried out from 1993 to 1995 on Wye College Estate, UK, comparing the use of dairy manure compost and inorganic fertiliser in forage maize production. Soil chemical (nutrient content) and biological (microbial biomass and activity) aspects were analysed at several stages of maize development. -

R&D Project 291 Riparian and Instream Species-Habitat

Draft Project Report R&D Project 291 Riparian and Instream Species-Habitat Relationships University of Leicester September 1992 R&D 291/3/W ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Authors L.E. Parkyn D.M. Harper C.D. Smith Publisher National Rivers Authority Rivers House Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol BS12 4UD Tel : 0454 624400 Fax : 0454 624409 © National Rivers Authority 1992 Project details NRA R&D Project 291 Project Leader: R. Howell, Welsh Region Contractor : University of Leicester CONTENTS ~ Page FOREWORD . ^ . - - ix SUMMARY xi RECOMMENDATIONS xiii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Statutory background 1 1.2 Scientific background 2 1.3 Outputs 4 2. RIPARIAN AND FLOODPLAIN HABITATS 5 2.1 Plant communities 5 2.1.1 Introduction 5 2.1.2 Riparian 5 2.1.3 Lotic 8 2.1.4 Lentic 8 2.2 Animal communities 9 2.2.1 Woody vegetation 9 2.2.2 Herbaceous vegetation 10 2.2.3 Litter and woody debris 11 2~2.5' Bare substrata 12 2.2.6 Lentic 13 3. INSTREAM HABITATS 15 3.1 Fish 15 3.1.1 Instream Flow Incremental Methodology 15 3.1.2 Habitat assessment and scoring systems 18 3.2 Aquatic invertebrates 19 3.2.1 Context 19 3.2.2 Background 21 3.2.3 Particulate substrata 25 3.2.4 Aquatic macrophytes 27 3.2.6 Woody debris 34 3.2.7 Tree roots / undercut hanks 35 3.2.8 Exposed rock 35 3.2.9 Unclassified habitat features 36 3.2.10 Habitat list 36 Page 4. FISH 37 4.1 Background 37 4.2 Trout CSalmo trutta and Oncorhynchus mykiss) 37 4.2.1 Habitat summary 37 4.2.2 Introduction 39 4.2.3 General character of trout streams 39 4.2.4 Life history 39 4.2.5 Spawning 39 4.2.6 Diet 40 -

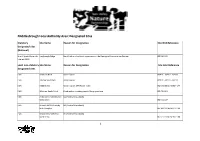

Middlesbrough Designations List

Middlesbrough Local Authority Area: Designated Sites Statutory Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference designated sites (National) Site of Special Scientific Langbaurgh Ridge Identified as of national importance in the Geological Conservation Review. NZ 556 121 Interest (SSSI) Local non-statutory Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference designated sites LWS Newham Beck Watercourse NZ51C - NZ41X - NZ41Y LWS Marton West Beck Watercourse NZ51C - NZ41X - NZ41Y LWS Middlebeck Watercourse; M4 (Water Vole) NZ 521 188 to NZ 527 177 LWS Whinney Banks Pond Pond and surrounding marsh/damp grassland NZ 476 184 LWS Anderson's Field (Marton G1 (Neutral Grasslands) West Beck) NZ 515 147 LWS Berwick Hill & Ormesby G1 (Neutral Grasslands) Beck Complex NZ 508 192 to NZ 519 169 LWS Bonny Grove (Marton G1 (Neutral Grasslands) West Beck) NZ 527 139 to NZ 522 138 1 Local non- Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference statutory designated sites LWS Maltby Beck G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 471 135 LWS Maltby Beck G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 474 135 LWS Bluebell Beck Complex G1 (Neutral Grasslands); M4 (Water Vole) NZ 471 170 to NZ 478 164 LWS Maze Park U1 (Urban Grasslands) NZ 469 192 LWS Old River Tees C1 (Saltmarsh) NZ 472 182 LWS Plum Tree Pasture G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 468 143 LWS Grey Towers Park W2 (Broad-leaved Woodland and Replanted Ancient Woodland) (formerly Poole Hospital) NZ 533 135 LWS Stainsby Wood W1 (Ancient Woodland) NZ 463 148 LWS Teessaurus Park U1 (Urban Grasslands) NZ 486 218 LWS Thornton Wood and Pond