The Streams of the New Forest: a Study in Drainage Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Forest Audax Events on 23Rd May 2021 Starting from Lymington

New Forest Audax Events on 23rd May 2021 Starting from Lymington. (Open air public space – according to restrictions in force at the time) There will be no arranged refuelling venues as controls. Proof of passage will be by gathering “information controls” as you travel. There are many opportunities for refreshment on the courses but to avoided the risk of crowding specific places it will be up to riders to decide where, and if, to stop. New Forest Excursion – 207km (125miles) This event explores every corner and all of the varied New Forest landscapes. The route visits Burley, the western escarpment of the Forest in the Avon Valley, the edge of the Wiltshire Downs, and Cranborne Chase, before returning through the heart of the Forest across Stoney Cross plain through Lyndhurst and Beaulieu to the Solent coastal nature reserve at Lepe. Then a loop back northwards to Redlynch and Hale before a grand finale down the Ornamental Drives, through Brockenhurst and more coastal fringes to the Arrivee. Entry fee: £5 (+ £3 temporary membership fee, if you are not a member of AUK or CTC) Includes: Route sheet, gpx track, brevet card, and AUK validation fee . Enter via the Audax Uk Website Here: https://audax.uk/event-details?eventId=9013 New Forest Day Out - 107km (66miles) This event explores the centre and west of the New Forest with a turning point at the Braemore near Fordingbridge. Entry fee: £4 (No SAE required for postal entries.) (+ £3 temporary membership fee, if you are not a member of AUK or Cycling UK) Includes: Route sheet, gpx track, brevet card and AUK validation fee. -

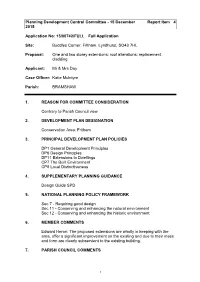

Buddles Corner, Fritham, Lyndhurst SO43

Planning Development Control Committee - 15 December Report Item 4 2015 Application No: 15/00742/FULL Full Application Site: Buddles Corner, Fritham, Lyndhurst, SO43 7HL Proposal: One and two storey extensions; roof alterations; replacement cladding Applicant: Mr & Mrs Day Case Officer: Katie McIntyre Parish: BRAMSHAW 1. REASON FOR COMMITTEE CONSIDERATION Contrary to Parish Council view 2. DEVELOPMENT PLAN DESIGNATION Conservation Area: Fritham 3. PRINCIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN POLICIES DP1 General Development Principles DP6 Design Principles DP11 Extensions to Dwellings CP7 The Built Environment CP8 Local Distinctiveness 4. SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING GUIDANCE Design Guide SPD 5. NATIONAL PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK Sec 7 - Requiring good design Sec 11 - Conserving and enhancing the natural environment Sec 12 - Conserving and enhancing the historic environment 6. MEMBER COMMENTS Edward Heron: The proposed extensions are wholly in keeping with the area, offer a significant improvement on the existing and due to their mass and form are clearly subservient to the existing building. 7. PARISH COUNCIL COMMENTS 1 Bramshaw Parish Council: Recommend permission: • Removes a flat roof extension which isn't in keeping with the property or the conservation area. • It is an improvement on what is already there with the resultant changes being minor to the visual amenity of the local area, particularly as the work is to the rear of the property and does not alter the appearance of the front of the property. • The house will become a more complete dwelling for the current occupier by providing a house suitable for modern living (particularly with the provision of a downstairs WC). • The two storey extension will, because of its reduced height be subservient to the original property. -

T4 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

T4 bus time schedule & line map T4 Totton - Cadnam - Totton View In Website Mode The T4 bus line (Totton - Cadnam - Totton) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Totton: 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (2) West Totton: 2:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest T4 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next T4 bus arriving. Direction: Totton T4 bus Time Schedule 56 stops Totton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational St Theresas Church, Totton Tuesday 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Asda, Totton Ringwood Road, Totton And Eling Civil Parish Wednesday Not Operational Bagber Road, Totton Thursday 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Friday Not Operational Forest Park School, Totton Southern Gardens, Totton And Eling Civil Parish Saturday Not Operational Calmore Corner, West Totton Graddidge Way, West Totton Galsworthy Road, Totton And Eling Civil Parish T4 bus Info Direction: Totton Hazel Farm Road, West Totton Stops: 56 Redwood Gardens, Totton And Eling Civil Parish Trip Duration: 50 min Line Summary: St Theresas Church, Totton, Asda, Crabbs Way, West Totton Totton, Bagber Road, Totton, Forest Park School, Totton, Calmore Corner, West Totton, Graddidge Way, Goodies, West Totton West Totton, Hazel Farm Road, West Totton, Crabbs Way, West Totton, Goodies, West Totton, Morrisons, Morrisons, West Totton West Totton, Stonechat Drive, West Totton, Michigan Skylark Walk, Totton And Eling Civil Parish Way, Calmore, Amey Gardens, Calmore, The Drove, Calmore, Farm Close, Calmore, Woodhaven & Stonechat Drive, -

Beaulieu River

2 9 1 3 10 4 LCA 26: BEAULIEU RIVER 11 21 13 6 22 Industry at Fawley visible on the eastern skyline 12 LCA 26: BEAULIEU RIVER LocationLocation of Landscape of LCA Character in the National Area 26, Park Beaulieu River (LCA 26) 5 23 27 8 14 26 20 25 24 15 7 19 18 16 17 N Not to scale Grey area is land outside of the New Forest National Park 146 LCA 26: BEAULIEU RIVER Component landscape types within LCA 26 Area in shadow- outside National Park National Park boundary LCA 26 © Crown Copyright and Database Right 2014. Ordnance Survey 1000114703. Not to scale All of this LCA lies within the New Forest National Park. 1. Coastal Fringe 13. Enclosed Farmland and Woodland 21. Historic Parkland 147 LCA 26: BEAULIEU RIVER A. LANDSCAPE DESCRIPTION Key landscape characteristics Large scale undulating estate landscape Estate influence evident around Beaulieu and encompassing the lower reaches of the Beaulieu Exbury with brick boundary walls, large houses and River with outstanding wetland flora. brick estate cottages or lodges A well wooded river valley with pockets of enclosed The wooded valley creates a setting for Beaulieu, farmland, including some former heathland, and the focus of the valley, with its attractive Mill Pond, extensive areas of ancient woodland and timber Palace House and Abbey ruins. plantations within the New Forest perambulation Linear settlement along Kings Copse Road faces boundary. onto Blackwell Common. Minor roads wind their way up the valley, along Strong commoning communities leafy lanes and through tunnels in the trees. Restricted views due to enclosure and extensive Survival of Open Forest grazing on the foreshore. -

Excavation of Three Romano-British Pottery Kilns in Amberwood Inglosure, Near Fritham, New Forest

EXCAVATION OF THREE ROMANO-BRITISH POTTERY KILNS IN AMBERWOOD INGLOSURE, NEAR FRITHAM, NEW FOREST By M. G. FULFORD INTRODUCTION THE three kilns were situated on the slopes of a slight, marshy valley (now marked by a modern Forestry Commission drain) which runs south through the Amberwood Inclosure to the Latchmore Brook (fig. i). The subsoil consists of the clay and sandy gravel deposits of the Bracklesham beds. Kilns i (SU 20541369) and 2 are at the head of this shallow valley at about 275 feet O.D. on a south-east facing slope, Fig. 1. Location maps to show the Amberwood and other Romano-British kilns in the New Forest. 5 PROCEEDINGS FOR THE YEAR 1971 while kiln 3 (at SU 20631360) is some 100 metres to the south on the eastern side of the valley at 250 feet O.D. Previous work in the New Forest does not record any kiln in the Amberwood Inclosure. A hoard of coins was found (Akerman, 1853) in this area, but only two of the coins are recorded; one of Julian (355-363) and one of Valens (364-78). Sumner (1927) records finding a quern-stone and pottery at about SU 20701383, and Pasmore (1967) lists a series of possible sites within the Inclosure. Other find spots on the map in Sumner (1927, facing p. 85) suggest he may have been the first to find the waste heaps of kiln 1, but kiln 3 was only traced by Mr. A. Pasmore after the withdrawal of timber following the felling of hardwood in 1969-70. -

16/00740/FULL Full Application Site

Planning Development Control Committee - 15 November Report Item 5 2016 Application No: 16/00740/FULL Full Application Site: McDonalds Restaurant (formerly Little Chef), A31 Picket Post, Ringwood, BH24 3HN Proposal: Reconfiguration of car park to provide 6 no. additional car parking spaces. Applicant: McDonald's Restaurants Limited Case Officer: Katie McIntyre Parish: ELLINGHAM HARBRIDGE AND IBSLEY 1. REASON FOR COMMITTEE CONSIDERATION Contrary to Parish Council view 2. DEVELOPMENT PLAN DESIGNATION Site of Special Scientific Interest Special Protection Area Special Area of Conservation Ramsar Site Tree Preservation Order 3. PRINCIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN POLICIES DP1 General Development Principles CP8 Local Distinctiveness CP2 The Natural Environment 4. SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING GUIDANCE Not applicable 5. NATIONAL PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK Sec 11 - Conserving and enhancing the natural environment 6. MEMBER COMMENTS None received 7. PARISH COUNCIL COMMENTS Ellingham, Harbridge & Ibsley Parish Council: Recommend refusal: 1 • Best course of action would be for this site to be closed during the works, as there is no space for any contractors vehicles to park and this application is simply pushing all responsibility onto an as yet unnamed contractor whose employees are not permitted to park on site with nowhere to park apart from the protected (SSSI) verges. • Consider the concerns raised in earlier response (summarised below) to the previously withdrawn planning application 16/00303 have not been addressed in this application, as it does not provide the method statements to be supplied by the contractor regarding the storage of materials, details of safety measures of the movement of large 4 axle vehicles around the still open site, parking of contractors off site and not on the SSSI verge, and the storage of contractor vehicles and machinery. -

An Inventory of Churchyard Yews Along the Hampshire Test and Its Tributaries

Hampshire Yews An Inventory of Churchyard Yews along the Hampshire Test and its tributaries Part 3 – The Lower Test By Peter Norton Introduction: The Test rises at Ashe, just to the west of Basingstoke and on its way through Hampshire is fed from many streams and brooks emanating from the west and one main stream from the east. After flowing through Stockbridge and Romsey, it converges in Southampton with the Itchen some 40 miles from its source. At this point it becomes Southampton Water which flows into the Solent before reaching the open sea. The west tributaries include the Bourne Rivulet, Anton, Wallop Brook, Dun, Blackwater and Bartley Water. The east tributaries include the Dever, Tadburn and Tanners Brook. The Lower Test This is the last of three reports that split the River Test into three sections; Upper, Middle and Lower. The Lower Test is described as from just north of Romsey to its confluence with the Itchen, covering a distance of some 12 miles by road. Along its path it is joined by the Tadburn, Blackwater, Bartley Water and Tanners Brook. All of the towns and villages along this part of the Test and its tributaries were included, with 18 churches visited, of which 12 contained yews. All churches are in Hampshire unless otherwise stated. Of the 26 yews noted at these sites, 11 had measurements recorded. The graph below groups the measured yews ac- cording to their girth, presented here in metric form. It does not include yews whose girth was estimated*. Where a tree has been measured at different heights, the measurement taken closest to the root/ground is used for this graph. -

Hampshire Superfast Broadband Programme

Hampshire Superfast Broadband Programme New Forest Consultative Panel Lyndhurst 7 December 2018 Glenn Peacey Shaun Dale Hampshire County Council Openreach [email protected] [email protected] Superfast Broadband Checker HCC Contract 2 HCC Contract 1 Commercially Funded Coverage Hampshire Superfast Programme • Commercially Funded Upgrades reach 80% of premises by end of 2013 • Government Intervention 2013 - 2019 – Wave 1 - £11m • 64,500 premises upgraded 2013 - 2015 – Wave 2 - £18m (£9.2m from HCC) • 34,500 premises 2016 - 2018 – Wave 2 Extension - £6.8m • 8,500 premises 2018 – 2019 • Universal Service Obligation 2020 • 100% FTTP Coverage by 2033 Superfast Broadband Programme Upgrading connections to more than 107,000 premises Over 12,000 Fibre to the Premises (FTTP) • Increase coverage from 80% to more than 97.4% by end of 2019 • 15-20,000 premises across Hampshire • Looking for new funding streams to reach the last 2.6%, likely cost £20-£40m • Better Broadband Scheme Offers 4G, satellite and fixed wireless solutions for premises with a sub-2Mbps speed The scheme was extended until end 2018 We have issued 900 codes for installations • A national Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme has been launched, with the aim of extending full fibre coverage specifically to small/medium-sized enterprises Internet Telephone Exchange Exchange Only lines Too far from the cabinet New Forest Upgrades Exchange Name: 219 Structures Planned ASHURST 148 Structures Live BEAULIEU BRANSGORE More than 500 FTTP Premises connected BROCKENHURST BURLEY -

9040 the London Gazette, 2Nd July 1984 Department Of

9040 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 2ND JULY 1984 Companies Registration Office, During 28 days from 2nd July 1984 copies of the draft Companies House, Crown. Way, Order and relevant plan may be inspected at all reasonable Maindy, Cardiff CF4 3UZ hours at the Portsmouth City Council offices. Information Desk, Ground Floor, Civic Offices, Guildhall Square, 2nd July 1984 Portsmouth, and may be obtained free of charge from the Secretary of State (quoting ref. DSE 5237/35/1/L/084) at COMPANIES ACT 1948 the address stated below. Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 353 (5) of the Within the above-mentioned period of 28 days, any per- Companies Act 1948. that the names of the undermentioned son may by notice to the Secretary of State for Transport Companies have been struck off the Register. Such Com- (ref. DSE 5237/35/1/L/084), at his address of the Director panies are accordingly dissolved as from the date of the (Transport), Departments of the Environment and Trans- publication of this notice. This list may include Companies port, South East Regional Office, 74 Epsom Road, Guild- which are being removed from the Register at their own ford, Surrey GUI 2BL, object to the making of the request. Order. LIST 1448 P. J. Carter, A Senior Executive Officer in the Depart- ment of Transport. (Ref. T9840/28/0600.) (3 SI) Alpha Chemie (U.K.) Limited Bryvon Limited The Trunk Road (All) (Picket Post) (Prohibition of U- Tiirns) Order 1984 Contract Furnishers (Swansea) Limited The Secretary of State for Transport proposes to make an Order under sections 1 (1), (2) and (3) of the Road Traffic Draughting & Design (Altrincham) Limited Regulation Act 1967, as amended by Part IX of the Transport Act 1968 on the Folkestone-Honiton Trunk Road E. -

Peat Database Results Hampshire

Baker's Rithe, Hampshire Record ID 29 Authors Year Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 6926 1041 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Preserved timbers (oak and yew) on peat ledge. One oak stump in situ. Peat layer 0.15-0.26 m deep [thick?]. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available -1 m OD Yes Notes 14C details ID 12 Laboratory code R-24993/2 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description [-1 m OD] Oak stump Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3735 ± 60 BP 2310-1950 cal. BC Notes Stump BB Bibliographic reference Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 'Our changing coast; a survey of the intertidal archaeology of Langstone Harbour, Hampshire', Hampshire CBA Research Report 12.4 Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 86 Bury Farm (Bury Marshes), Hampshire Record ID 641 Authors Year Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 3820 1140 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available Yes Notes 14C details ID 491 Laboratory code Beta-93195 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description SU 3820 1140 -0.16 to -0.11 m OD Transgressive contact. Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3080 ± 60 BP 3394-3083 cal. BP Notes Dark brown humified peat with some turfa. Bibliographic reference Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 'Stratigraphic architecture, relative sea-level, and models of estuary development in southern England: new data from Southampton Water' in ' and estuarine environments: sedimentology, geomorphology and geoarchaeology', (ed.s) Pye, K. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

River Avon at Bulford

River Avon at Bulford An Advisory Visit by the Wild Trout Trust June 2013 Contents Introduction Catchment and Fishery Overview Habitat Assessment Recommendations Making It Happen 2 Introduction This report is the output of a Wild Trout Trust visit undertaken on the Hampshire Avon on the Snake Bend Syndicate’s (SBS) water near Bulford, national grid reference (NGR) SU155428 to SU155428. The visit was requested by Mr Geoff Wilcox, who is the syndicate secretary and river keeper. The visit was focussed on assessing the habitat and management of the water for wild trout Salmo trutta. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Mr Wilcox. Throughout the report, normal convention is followed with respect to bank identification i.e. banks are designated Left Bank (LB) or Right Bank (RB) whilst looking downstream. Catchment and Fishery Overview The Hampshire Avon is recognised as one of the most important river habitats in the UK. It supports a diverse range of fish and invertebrates and over 180 different aquatic plant species. The Avon (and its surrounding water meadows) has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Area of Conservation (SAC); however, much of the Avon and its tributaries have been significantly modified for land drainage, agriculture, milling and even navigation. 3 The Avon begins its life as two separate streams known as the Avon West and the Avon East, rising near Devizes and the Vale of Pewsey respectively. The Avon West is designated as a SSSI whilst for reasons unknown, the Avon East is not.