Evidence from Colonial Punjab. ONLINE APPENDIX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATION, NATIONALISM and the PARTITION of INDIA: PARTITION the NATION, and NATIONALISM , De Manzoor Ehtesham

NATION, NATIONALISM AND THE PARTITION OF INDIA: TWO MOMENTS FROM HINDI FICTION* Bodh Prakash Ambedkar University, Delhi Abstract This paper traces the trajectory of Muslims in India over roughly four decades after Independ- ence through a study of two Hindi novels, Rahi Masoom Reza’s Adha Gaon and Manzoor Ehtesham’s Sookha Bargad. It explores the centrality of Partition to issues of Muslim identity, their commitment to the Indian nation, and how a resurgent Hindu communal discourse particularly from the 1980s onwards “otherizes” a community that not only rejected the idea of Pakistan as the homeland for Muslims, but was also critical to the construction of a secular Indian nation. Keywords: Manzoor Ehtesham, Partition in Hindi literature, Rahi Masoom. Resumen Este artículo estudia la presencia del Islam en India en las cuatro décadas siguientes a la Independencia, según dos novelas en hindi, Adha Gaon, de Rahi Masoom Reza y Sookha Bargad, de Manzoor Ehtesham. En ambas la Partición es el eje central de la identidad mu- sulmana, que en todo caso mantiene su fidelidad a la nación india. Sin embargo, el discurso del fundamentalismo hindú desde la década de 1980 ha ido alienando a esta comunidad, 77 que no solo rechazó la idea de Paquistán como patria de los musulmanes, sino que fue fundamental para mantener la neutralidad religiosa del estado en India. Palabras clave: Manzoor Ehtesham, Partición en literatura hindi, Rahi Masoom. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25145/j.recaesin.2018.76.06 Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, 76; April 2018, pp. 77-89; ISSN: e-2530-8335 REVISTA CANARIA 77-89 DE ESTUDIOS PP. -

FIRMS in AOR of RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD

Appendix-A FIRMS IN AOR OF RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD 1 M/s A.A Textile Processing Industries, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 2 M/s A.B Exports (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 3 M/s A.M Associates, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 4 M/s A.M Knit Wear, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 5 M/s A.S Chemical, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 6 M/s A.T Impex, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 7 M/s AA Brothers Chemical Traders, Sialkot Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 8 M/s AA Fabrics, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 9 M/s AA Spinning Mills Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 10 M/s Aala Production Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 11 M/s Aamir Chemical Store, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 12 M/s Abbas Chemicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab M/s Abdul Razaq & Sons Tezab and Spray Centre, 13 Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Toba Tek Singh 14 M/s Abubakar Anees Textiles, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 15 M/s Acro Chemicals, Lahore Toluene & MEK Punjab 16 M/s Agritech Ltd, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 17 M/s Ahmad Chemical Traders, Muridke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 18 M/s Ahmad Chemmicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 19 M/s Ahmad Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Khanewal Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 20 M/s Ahmed Chemical Traders, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 21 M/s AHN Steel, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 22 M/s Ajmal Industries, Kamoke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 23 M/s Ajmer Engineering Electric Works, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 24 M/s Akbari Chemical Company, -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

J&K Ready for Big Transformation in Wake of Post-Art 370

TRULY TIMES 3 LOCAL JAMMU, MONDAY, MARCH 15, 2021 J&K ready for big transformation in wake Dimple protest against new liquor policy TT CORRESPONDENT of post-Art 370 period: Prof Agnihotri JAMMU, MAR. 14: Today again Sunil Dimple President Mission Statehood SKUAST VC emphasizes on exploring agriculture, horticulture potentials Jammu Kashmir and Jammu West Assembly Movement TT CORRESPONDENT because they decided to inno- led a strong protest against JAMMU, MAR. 14: The vate and experiment and the new Liquor Policy and Union Territory (UT) of J&K diversify. the Rising Unemployment. is ready for big transforma- He said the Corona period The Copies of the Govt new tion in the wake of post- has taught new lessons in Liquor policy & advertise- Article 370 period, more in farming after society realised ment notifications of the the economic fields where it the need for organic products locations for the allotment has been a laggard for various like gilloy, turmeric, vends proposal to open more Photo by Surinder political reasons for years alluyvera. wine shops to Collect said our mothers' sisters all He questions the LG Manoj together. "Within their limited Revenue by making people, over jammu Kashmir in rural Sinah that what are the terms These observations were resources farmers can go for youths liquor Drinking and urbon ares, are agitating and conditions set with the made by Dr Kuldeep integrated farming, besides addicted. for the closure of wine shops investors while Signing 450 Agnihotri, Vice Chancellor of taking new initiatives in pro- Addressing the protestors, as they suffering. Women MOUs, Worth Rs 23,000 Cr Central University of cessing and value addition of Sunil Dimple warned LG folk say their husbands, for Industrial Investments.70 Himachal Pradesh while their produce", he added. -

Qt7vk4k1r0 Nosplash 9Eebe15

Fiction Beyond Secularism 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) 1. On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant, Dina Al-Kassim 2. Moses and Multiculturalism, Barbara Johnson, with a foreword by Barbara Rietveld 3. The Cosmic Time of Empire: Modern Britain and World Literature, Adam Barrows 4. Poetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric Modernity, Michelle Clayton 5. Disarming Words: Empire and the Seductions of Translation in Egypt, Shaden M. -

Internal Classification of Scheduled Castes: the Punjab Story

COMMENTARY “in direct recruitments only and not in Internal Classification of promotion cases”.2 Learning from the Punjab experience, the state government Scheduled Castes: of Haryana too decided in 1994 to divide its scheduled caste population in two blocks, The Punjab Story A and B, limiting 50 per cent of all the seats for the chamars (block B) and offer- ing 50 per cent of the seats to non-chamars Surinder S Jodhka, Avinash Kumar (block A) on preferential basis. This arrangement worked well until Much before the question of n the recommendations of the 2005 when the Punjab and Haryana High quotas within quotas in jobs Ramachandra Rao Commission, Court directed the two state governments reserved for the scheduled castes Othe government of Andhra about the “illegality” of the provision in Pradesh decided in June 1997 to classify response to a writ petition by Gaje Singh, acquired prominence in Andhra its scheduled caste (SC) population into A, a chamar from the region. The petitioner Pradesh, Punjab had introduced a B, C and D categories and fixed a specific cited the Supreme Court judgments twofold classification of its SC quota of seats against each of the caste against the sub-classification of scheduled population. When the Andhra categories roughly matching the propor- castes in the case of Andhra Pradesh. tion of their numbers in the total popula- Though, the Punjab state government case went to court, Punjab had to tion. This was done in response to the pow- quickly worked a way out of it and turned rework its policy. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

Admission Brochure 2021-22 Undergraduate and Post Graduate Programmes

Admission Brochure 2021-22 Undergraduate and Post Graduate Programmes Email: [email protected], [email protected] © Published by the Student Services Division Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University Delhi ii Admission Brochure 2021-22 Admission Brochure 2021-22 iii iv Admission Brochure 2021-22 Admission Brochure 2021-22 v ImportantImportant Note/Disclaimer:Note/Disclaimer: • The contents of the brochure are on the basis of the policies available as on this date of release of Admission Brochure for Academic Session 2021-22. The information which is not available in the Admission Brochure shall be uploaded on the University website: www.aud.ac.in and therefore all the candidates desirous of seeking admission are hereby advised to regularly visit the University website for additional information. • In view of the challenges brought about by Covid-19, any change in the procedure for personal appearance of applicants for entrance examination/ trials for CCA and Sports, as well as for verification of certificates shall be notified in due course by the Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Delhi on its website: www. aud.ac.in. Applicants are advised to monitor the same and act as directed. • The University reserves the right to revise, update or delete any part of this brochure without giving any prior notice. Any change made shall be updated on the University website. vi Admission Brochure 2021-22 IMPORTANT NOTE/DISCLAIMER: IMPORTANT S.No Contents Page No 1 Lieutenant Governor’s Message ii 2 Chief Minister’s Message iii 3 Deputy Chief Minister’s Message iv 4 Vice Chancellor’s Message v 5 Registrar’s Message vi 6 About Dr. -

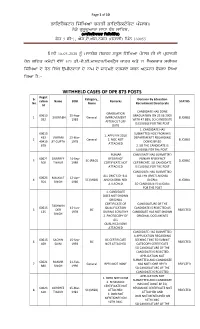

WITHHELD CASES of DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr

Page 1 of 10 fwierYktr is`iKAw BrqI fwierYktoryt pMjwb[ nyVy gurUduAwrw swcw DMn swihb, (mweIkrosw&t ibilifMg) Pyz 3 bI-1, AYs.ey.AYs.ngr (mohwlI) ipMn 160055 imqI 16.03.2020 nUM mwnXog s`kqr skUl is`iKAw pMjwb jI dI pRDwngI hyT giTq kmytI v`loN 873 fI.pI.eI.mwstr/imstRYs kwfr Aqy 74 lYkcrwr srIrk is`iKAw dy hyT ilKy aumIdvwrW dy nwm dy swhmxy drswey kQn Anuswr PYslw ilAw igAw hY:- WITHHELD CASES OF DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr. Category_ Decision By Education ration Name DOB Remarks STATUS No. Name Recruitment Directorate Id CANDIDATE HAS DONE GRADUATION 60610 25-Aug- GRADUATION ON 25.06.2005 1 SAURABH General IMPROVEMENT ELIGIBLE 352 1983 WITH 47.88%, SO CANDIDATE AFTER CUT OFF IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST DATE 1. CANDIDATE HAS 60613 SUBMITTED NOC FROM HIS 1. APPLY IN 2016 433 VIKRAM 23-Mar- DEPARTMENTT REGARDING 2 General 2. NOC NOT ELIGIBLE 40410 JIT GUPTA 1978 DOING BP.ED ATTACHED 679 2. SO THE CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST. PUNJAB CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED 60621 GURPREE 14-Sep- RESIDENCE PUNJAB RESIDENCE 3 SC (R&O) ELIGIBLE 500 T KAUR 1989 CERTIFICATE NOT CERTIFICATE SO CANDIDATE ATTACHED IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED ALL DMC'S OF B.A. ALL THE DMC'S AND BA 60625 MALKEET 12-Apr- 4 SC (M&B) AND DEGREE NOT DEGREE ELIGIBLE 504 SINGH 1986 ATTACHED SO CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST 1. CANDIDATE DOES NOT SHOWN ORIGINAL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDATURE OF THE TASHWIN 60615 15-Jun- QUALIFICATION CANDIDATE IS REJECTED AS 5 DER BC REJECTED 125 1978 DURING SCRUTINY CANDIDATE HAS NOT SHOWN SINGH 2. -

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

East Bengal Tables , Vol-8, Pakistan

M-Int 17 5r CENSlUJS Of PAIK~STAN, ~95~ VOLUME 6 REPORT & TABLES BY GUl HASSAN, M. I. ABBASI Provincial Superintendent of Census, SIND Published by the Man.ager of Publication. Price Rs. J 01-1- FIRST CENSUS OF PAKISTAN. 1951 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS Bulletins No. I--Provisional Tables of Population. No. 2--Population according to Religion. No.3-Urban and Rural Population and Area. No.4-Population according to Economic Categories. Village Lists The Village list shows the name of every Village in Pakistan in its place in the ltthniftistra tives organisation of Tehsils, Halquas, Talukas, Tapas, SUb-division's Thanas etc. The names are given in English and in the appropriate vernacular script, and against _each is shown the area, population as enumerated in the Census, tbe number of houses, and local details such as the existence of Railway Stations, Post Offices, Schools, Hospitals etc. The Village -list. is issued in separate booklets for each District or group of Districts. Census Reports Printed Vol. 2-Baluchistan and States Union Report and Tables. Vol. 3.-East Bengal Report and Tables. Vol. 4-N.-W. F. P. and Frontier Regions Report :md Tables. Vol. 6-Sind and Khairpur State Report and Tabla Vol 8-East Pakistan Tables of Economic CharacUi Census Reports (in course of preparation.) Vol. I-General Report and Tables for Pakistan, shcW)J:}g Provincial Totals. Vol. 5-Punjab and Bahawalpur State Report and Tables. Vol. 7-West Pakistan Tables ot Economic Characteristics.- PREF ACE, This Census Report for the province of Sind and Khairpur State is one of the series 'of volumes in which the results ofothe 1951 €ensus of Pakistan are recorded.