Role of Arginine Methylation in Alternative Polyadenylation of VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) Pre-Mrna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subcellular RNA Profiling Links Splicing and Nuclear DICER1 to Alternative Cleavage and Polyadenylation

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Subcellular RNA profiling links splicing and nuclear DICER1 to alternative cleavage and polyadenylation Jonathan Neve1#, Kaspar Burger2#, Wencheng Li3, Mainul Hoque3, Radhika Patel1, Bin Tian3, Monika Gullerova2* and Andre Furger1* Affiliations: 1 Department of Biochemistry, South Parks Road, University of Oxford, OX1 3QU, UK 2 Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, South Parks Road, University of Oxford, OX1 3RE, UK 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ 07103, USA *Corresponding authors: Andre Furger Email: [email protected] Monika Gullerova Email: [email protected] # authors contributed equally Running Title: APA and subcellular fractionation Key words: alternative polyadenylation, mRNA, subcellular fractionation, DICER1 1 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ABSTRACT Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA) plays a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression across eukaryotes. Although APA is extensively studied, its regulation within cellular compartments and its physiological impact remains largely enigmatic. Here, we employed a rigorous subcellular fractionation approach to compare APA profiles of cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA fractions from human cell lines. This approach allowed us to extract APA isoforms that are subjected to differential regulation and provided us with a platform to interrogate the molecular regulatory pathways that shape APA profiles in different subcellular locations. Here we show that APA isoforms with shorter 3’UTRs tend to be overrepresented in the cytoplasm and appear to be cell type specific events. -

The Reciprocal Regulation Between Splicing and 3-End Processing

Advanced Review The reciprocal regulation between splicing and 30-end processing Daisuke Kaida* Most eukaryotic precursor mRNAs are subjected to RNA processing events, including 50-end capping, splicing and 30-end processing. These processing events were historically studied independently; however, since the early 1990s tremendous efforts by many research groups have revealed that these processing factors interact with each other to control each other’s functions. U1 snRNP and its components negatively regulate polyadenylation of precursor mRNAs. Impor- tantly, this function is necessary for protecting the integrity of the transcriptome and for regulating gene length and the direction of transcription. In addition, physical and functional interactions occur between splicing factors and 30-end processing factors across the last exon. These interactions activate or inhibit spli- cing and 30-end processing depending on the context. Therefore, splicing and 30- end processing are reciprocally regulated in many ways through the complex protein–protein interaction network. Although interesting questions remain, future studies will illuminate the molecular mechanisms underlying the recipro- cal regulation. © 2016 The Authors. WIREs RNA published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. How to cite this article: WIREs RNA 2016, 7:499–511. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1348 INTRODUCTION regulate each other on the transcription apparatus. In addition, because these events are carried out co- n eukaryotic cells, most precursor mRNAs (pre- transcriptionally in most cases, such factors can exist ImRNAs) consist of protein-coding regions, exons, on pre-mRNA just after synthesis of the binding sites 1,2 and intervening regions, introns. The pre-mRNAs of processing factors, suggesting that the factors are subjected to splicing to remove introns and to affect each other on the pre-mRNA. -

Targeted Cleavage and Polyadenylation of RNA by CRISPR-Cas13

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/531111; this version posted January 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Targeted Cleavage and Polyadenylation of RNA by CRISPR-Cas13 Kelly M. Anderson1,2, Pornthida Poosala1,2, Sean R. Lindley 1,2 and Douglas M. Anderson1,2,* 1Center for RNA Biology, 2Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, U.S.A., 14642 *Corresponding Author: Douglas M. Anderson: [email protected] Keywords: NUDT21, PspCas13b, PAS, CPSF, CFIm, Poly(A), SREBP1 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/531111; this version posted January 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Post-transcriptional cleavage and polyadenylation of messenger and long noncoding RNAs is coordinated by a supercomplex of ~20 individual proteins within the eukaryotic nucleus1,2. Polyadenylation plays an essential role in controlling RNA transcript stability, nuclear export, and translation efficiency3-6. More than half of all human RNA transcripts contain multiple polyadenylation signal sequences that can undergo alternative cleavage and polyadenylation during development and cellular differentiation7,8. Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation is an important mechanism for the control of gene expression and defects in 3’ end processing can give rise to myriad human diseases9,10. -

Widespread Mrna Polyadenylation Events in Introns Indicate Dynamic Interplay Between Polyadenylation and Splicing

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Letter Widespread mRNA polyadenylation events in introns indicate dynamic interplay between polyadenylation and splicing Bin Tian,1 Zhenhua Pan, and Ju Youn Lee Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, New Jersey Medical School, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey 07101, USA mRNA polyadenylation and pre-mRNA splicing are two essential steps for the maturation of most human mRNAs. Studies have shown that some genes generate mRNA variants involving both alternative polyadenylation and alternative splicing. Polyadenylation in introns can lead to conversion of an internal exon to a 3Ј terminal exon, which is termed composite terminal exon, or usage of a 3Ј terminal exon that is otherwise skipped, which is termed skipped terminal exon. Using cDNA/EST and genome sequences, we identified polyadenylation sites in introns for all currently known human genes. We found that ∼20% human genes have at least one intronic polyadenylation event that can potentially lead to mRNA variants, most of which encode different protein products. The conservation of human intronic poly(A) sites in mouse and rat genomes is lower than that of poly(A) sites in 3Ј-most exons. Quantitative analysis of a number of mRNA variants generated by intronic poly(A) sites suggests that the intronic polyadenylation activity can vary under different cellular conditions for most genes. Furthermore, we found that weak 5Ј splice site and large intron size are the determining factors controlling the usage of composite terminal exon poly(A) sites, whereas skipped terminal exon poly(A) sites tend to be associated with strong polyadenylation signals. -

Mrna Editing, Processing and Quality Control in Caenorhabditis Elegans

| WORMBOOK mRNA Editing, Processing and Quality Control in Caenorhabditis elegans Joshua A. Arribere,*,1 Hidehito Kuroyanagi,†,1 and Heather A. Hundley‡,1 *Department of MCD Biology, UC Santa Cruz, California 95064, †Laboratory of Gene Expression, Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo 113-8510, Japan, and ‡Medical Sciences Program, Indiana University School of Medicine-Bloomington, Indiana 47405 ABSTRACT While DNA serves as the blueprint of life, the distinct functions of each cell are determined by the dynamic expression of genes from the static genome. The amount and specific sequences of RNAs expressed in a given cell involves a number of regulated processes including RNA synthesis (transcription), processing, splicing, modification, polyadenylation, stability, translation, and degradation. As errors during mRNA production can create gene products that are deleterious to the organism, quality control mechanisms exist to survey and remove errors in mRNA expression and processing. Here, we will provide an overview of mRNA processing and quality control mechanisms that occur in Caenorhabditis elegans, with a focus on those that occur on protein-coding genes after transcription initiation. In addition, we will describe the genetic and technical approaches that have allowed studies in C. elegans to reveal important mechanistic insight into these processes. KEYWORDS Caenorhabditis elegans; splicing; RNA editing; RNA modification; polyadenylation; quality control; WormBook TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 531 RNA Editing and Modification 533 Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing 533 The C. elegans A-to-I editing machinery 534 RNA editing in space and time 535 ADARs regulate the levels and fates of endogenous dsRNA 537 Are other modifications present in C. -

1 Novel Expression Signatures Identified by Transcriptional Analysis

ARD Online First, published on October 7, 2009 as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 on 7 October 2009. Downloaded from Novel expression signatures identified by transcriptional analysis of separated leukocyte subsets in SLE and vasculitis 1Paul A Lyons, 1Eoin F McKinney, 1Tim F Rayner, 1Alexander Hatton, 1Hayley B Woffendin, 1Maria Koukoulaki, 2Thomas C Freeman, 1David RW Jayne, 1Afzal N Chaudhry, and 1Kenneth GC Smith. 1Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and Department of Medicine, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK 2Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Roslin, Midlothian, EH25 9PS, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Paul Lyons or Prof Kenneth Smith, Department of Medicine, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK. Telephone: +44 1223 762642, Fax: +44 1223 762640, E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Key words: Gene expression, autoimmune disease, SLE, vasculitis Word count: 2,906 The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in their licence (http://ard.bmj.com/ifora/licence.pdf). http://ard.bmj.com/ on September 29, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. 1 Copyright Article author (or their employer) 2009. -

Four Factors Are Required for 3'-End Cleavage of Pre-Mrnas

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Four factors are required for 3'-end cleavage of pre-mRNAs Yoshio Takagaki, Lisa C. Ryner/ and James L. Manley Columbia University, Department of Biological Sciences, New York, New York 10027 USA We reported previously that authentic polyadenylation of pre-mRNAs in vitro requires at least two factors: a cleavage/specificity factor (CSF) and a fraction containing nonspecific poly(A) polymerase activity. To study the molecular mechanisms underlying 3' cleavage of pre-mRNAs, we fractionated CSF further and show that it consists of four separable subunits. One of these, called specificity factor (SF; M„ —290,000), is required for both specific cleavage and for specific polyadenylation and thus appears responsible for the specificity of the reaction. Although SF has not been purified to homogeneity, several lines of evidence suggest that it may not contain an essential RNA component. Two other factors, designated cleavage factors I (CFI; M„ -130,000) and II (CFII; M„ —110,000), are sufficient to reconstitute accurate cleavage when mixed with SF. A fourth factor, termed cleavage stimulation factor (CstF; M„ —200,000), enhances cleavage efficiency significantly when added to a mixture of the three other factors. CFI, CFII, and CstF do not contain RNA components, nor do they affect specific polyadenylation in the absence of cleavage. Although these four factors are necessary and sufficient to reconstitute efficient cleavage of one pre-RNA tested, poly(A) polymerase is also required to cleave several others. A model suggesting how these factors interact with the pre-mRNA and with each other is discussed. -

Life and Death of Mrna Molecules in Entamoeba Histolytica

REVIEW published: 19 June 2018 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00199 Life and Death of mRNA Molecules in Entamoeba histolytica Jesús Valdés-Flores 1, Itzel López-Rosas 2, César López-Camarillo 3, Esther Ramírez-Moreno 4, Juan D. Ospina-Villa 4† and Laurence A. Marchat 4* 1 Departamento de Bioquímica, CINVESTAV, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico, 2 CONACyT Research Fellow – Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Campeche, Campeche, Mexico, 3 Posgrado en Ciencias Genómicas, Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico, 4 Escuela Nacional de Medicina y Homeopatía, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico In eukaryotic cells, the life cycle of mRNA molecules is modulated in response to environmental signals and cell-cell communication in order to support cellular homeostasis. Capping, splicing and polyadenylation in the nucleus lead to the formation of transcripts that are suitable for translation in cytoplasm, until mRNA decay occurs Edited by: in P-bodies. Although pre-mRNA processing and degradation mechanisms have usually Mario Alberto Rodriguez, been studied separately, they occur simultaneously and in a coordinated manner through Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico protein-protein interactions, maintaining the integrity of gene expression. In the past few Nacional (CINVESTAV-IPN), Mexico years, the availability of the genome sequence of Entamoeba histolytica, the protozoan Reviewed by: parasite responsible for human amoebiasis, coupled to the development of the so-called Mark R. Macbeth, “omics” technologies provided new opportunities for the study of mRNA processing and Butler University, United States Michael G. Sehorn, turnover in this pathogen. -

Post-Transcriptional Modification by / Hanaa Shawky Ragheb Supervised by Prof.Dr / Rasha El Tahan Course / Molecular Biology

Post-transcriptional modification By / Hanaa Shawky Ragheb Supervised by prof.dr / Rasha El Tahan Course / Molecular Biology Molecular biology: is a branch of science concerning biological activity at the molecular level. The field of molecular biology overlaps with biology and chemistry and in particular, genetics and biochemistry. A key area of molecular biology concerns understanding how various cellular systems interact in terms of the way DNA, RNA and protein synthesis function. Molecular biology looks at the molecular mechanisms behind processes such as replication, transcription, translation and cell function. One way to describe the basis of molecular biology is to say it concerns understanding how genes are transcribed into RNA and how RNA is then translated into protein. However, this simplified picture is currently be reconsidered and revised due to new discoveries concerning the roles of RNA. Central Dogma (Gene Expression): The central dogma of molecular biology explains that the information flow for genes is from the DNA genetic code to an intermediate RNA copy and then to the proteins synthesized from the code. The key ideas underlying the dogma were first proposed by British molecular biologist Francis Crick in 1958. Replication : DNA replication The formation of new and, hopefully, identical copies of complete genomes. DNA replication occurs every time a cell divides to form two daughter cells. Under the influence of enzymes, DNA unwinds and the two strands separate over short lengths to form numerous replication forks, each of which is called a replicon. The separated strands are temporarily sealed with protein to prevent re-attachment. A short RNA sequence called a primer is formed for each strand at the fork. -

Regulation of RNA Stability by Terminal Nucleotidyltransferases

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-11-2019 10:30 AM Regulation of RNA stability by terminal nucleotidyltransferases Christina Z. Chung The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Heinemann, Ilka U. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Biochemistry A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Christina Z. Chung 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Biochemistry Commons Recommended Citation Chung, Christina Z., "Regulation of RNA stability by terminal nucleotidyltransferases" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6255. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6255 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The dysregulation of RNAs has global effects on all cellular pathways. The regulation of RNA metabolism is thus tightly controlled. Terminal RNA nucleotidyltransferases (TENTs) regulate RNA stability and activity through the addition of non-templated nucleotides to the 3′-end. TENT-catalyzed adenylation and uridylation have opposing effects; adenylation stabilizes while uridylation silences or degrades RNA. All TENT homologs were initially characterized as adenylyltransferases; the identification of caffeine-induced death suppressor protein 1 (Cid1) in Schizosaccharomyces pombe as an uridylyltransferase led to the reclassification of many TENTs as uridylyltransferases. Cid1 uridylates mRNAs that are subsequently degraded by the exonuclease Dis-like 3′-5′ exonuclease 2 (Dis3L2), while the human homolog germline-development 2 (Gld2) has been associated with adenylation of mRNAs and miRNAs and uridylation of Group II pre-miRNAs. -

Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of the Human Spliceosome

letters to nature Acknowledgements amylose resin, and eluted with maltose under salt conditions We thank M. Bjøra˚s, L. Eide, K. Baynton, K. I. Kristiansen, J. Myllyharju, K. Skarstad and optimal for splicing (60 mM KCl)4,5. The products of the first and J. Klaveness for help and discussions, and L. Eide, K. Baynton and A. Klungland for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to M. Bjøra˚s for preparation of [3H]MNU- second catalytic steps of splicing were detected in the gel filtration labelled DNA substrates, to L. Eide for the construction of the plasmid for expression of fraction for both AdML and AdML-M3 pre-mRNAs (Fig. 1b, lanes 2 GST–AlkB, and to D. Daoudi for technical assistance. This work was supported by the and 5). In contrast, after binding to and elution from the amylose- Research Council of Norway and the Norwegian Cancer Society. E.S. also acknowledges affinity resin, only the splicing products of AdML-M3 spliceosomes support from the European Commission. were detected (lanes 3 and 6). We conclude that the spliceosomes are highly purified, as there is no detectable non-specific binding of Competing interests statement AdML spliceosomes to the affinity resin. This conclusion is bol- The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests. stered by the observation that spliceosomal small nuclear RNAs Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to P.Ø.F. (e-mail: [email protected]). .............................................................. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome Zhaolan Zhou*†, Lawrence J. Licklider†‡, Steven P. Gygi†‡ & Robin Reed† * Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA † Department of Cell Biology, ‡ Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

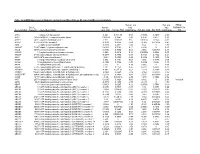

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde