The Realist Blueprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our 2021-22 Media Pack

formerly Scuttlebutt Europe 2021-22 1 Contents Pages 3 – 9 Seahorse Magazine 3 Why Seahorse 4 Display (Rates and Copy Dates) 5 Technical Briefing 6 Directory 7 Brokerage 8 Race Calendar 9 New Boats Enhanced Entry Page 10 “Planet Sail” On Course show Page 11 Sailing Anarchy Page 12 EuroSail News Page 13 Yacht Racing Life Page 14 Seahorse Website Graeme Beeson – Advertising Manager Tel: +44 (0)1590 671899 Email: [email protected] Skype: graemebeeson 2 Why Seahorse? Massive Authority and Influence 17,000 circulation 27% SUBS 4% APP Seahorse is written by the finest minds 14% ROW & RETAIL DIGITAL PRINT and biggest names of the performance 5,000 22% UK 28% IRC sailing world. 4,000 EUROPE 12% USA 3,000 International Exclusive Importance Political Our writers are industry pro's ahead of and Reach Recognition 2,000 journalists - ensuring Seahorse is the EUROPE A UK S UK 1,000 EUROPE U 14% RORC last word in authority and influence. ROW A A S ROW UK S ROW U 0 U ROW EUROPE IRC ORC RORC SUBS & APP 52% EUROPE (Ex UK) 27% ORC Seahorse is written assuming a high RETAIL SUBS level of sailing knowledge from it's The only sailing magazine, written Recognised by the RORC, IRC & from no national perspective, entirely ORC all of whom subscribe all readership - targetting owners and dedicated to sailboat racing. An their members and certificate afterguard on performance sailing boats. approach reflected by a completely holders to Seahorse as a benefit international reach adopt and adapt this important information into their design work. -

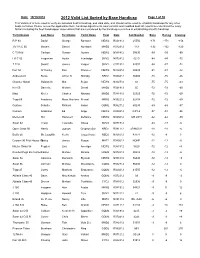

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

June 2018 Are We Having Fun Yet?

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE June 2018 Are We Having Fun Yet? A Wild Ride for the Kids – Sail4Kids Photo credit Anne Morley IN THIS ISSUE SAVE THE DATE In Memoriam: Larry Haig Blast from the Past May 26 Luau Jun 28 Board of Directors Mtg Commodore’s Report Turnback Canyon Regatta Recap May 26 Junior Clinic Jul 7 Independence Cup Board of Director Reports Fleet Updates Jun 2-3 Roadrunner Regatta /Optimist Jul 14, 21, 28 Dog Days Series Races Mid American Championship General Manager Report Finding Zebra Mussels Jul 26 Board of Directors Mtg Jun 8-10 J24 Circuit Stop Sailing Director Report by Steve Pervier Jul 27 MoonBurn Series Race Jun 9 ASA 101 Welcome New Members Late Spring Series Photos Jul 28 End of Series Dinner Jun 16, 23, 30 Dog Days Series Races 2018 Resolute Cup J22 Circuit Stop Photos by Scott Young Antigua Race Week / Jun 22 MoonBurn Series Race Volunteering in the BVI by James Parsons Photo credit Bill Records Larry Haig August 8, 1933 - May 19, 2018 Long time AYC member, Larry Haig, sadly lost his 4-month battle with cancer. Earlier in life, Larry worked as an engineer in the Detroit area. His engineering prowess and zest for life led him to racing cars as a hobby. Later he built and flew airplanes and met Bill Lear (Lear Jets) who was fascinated with one of Larry’s airplanes. Before coming to Texas, he raced a Hobie 33 for a number of years off the Atlantic coast of Florida. After joining the Club, Larry bought Blue Moon, a San Juan 24. -

![Herreshoff Collection Guide [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4530/herreshoff-collection-guide-pdf-1064530.webp)

Herreshoff Collection Guide [PDF]

Guide to The Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Collection The Design Records of The Herreshoff Manufacturing Company Bristol, Rhode Island The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collection Kurt Hasselbalch Frances Overcash & Angela Reddin The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections MIT Museum Cambridge, Massachusetts © 1997 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. Published by The MIT Museum 265 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 5 Historical Sketch 6 Scope and Content 8 Series Listing 10 Series Description I: Catalog Cards 11 Series Description II: Casting Cards (pattern use records) 12 Series Description III: HMCo Construction Record 13 Series Description IV: Offset Booklets 14 Series Description V: Drawings 26 Series Description VI: Technical and Business Records 38 Series Description VII: Half-Hull Models 55 Series Description VIII: Historic Microfilm 56 Description of Database 58 2 Acknowledgments The Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Project and this guide were made possible by generous private donations. Major funding for the Haffenreffer-Herreshoff Project was received from the Haffenreffer Family Fund, Mr. and Mrs. J. Philip Lee, Joel White (MIT class of 1954) and John Lednicky (MIT class of 1944). We are most grateful for their support. This guide is dedicated to the project donors, and to their belief in making material culture more accessible. We also acknowledge the advice and encouragement given by Maynard Bray, the donors and many other friends and colleagues. Ellen Stone, Manager of the Ships Plans Collection at Mystic Seaport Museum provided valuable cataloging advice. Ben Fuller also provided helpful consultation in organizing database structure. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the excellent work accomplished by the three individuals who cataloged and processed the entire Haffenreffer-Herrehsoff Collection. -

Martino, Gina M. "Women Warriors and the Mobilization of Colonial

Martino, Gina M. "Women Warriors and the Mobilization of Colonial Memory in the Nineteenth- Century United States." Women Warriors and National Heroes: Global Histories. .. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. 93–112. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350140301.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 18:44 UTC. Copyright © Boyd Cothran, Joan Judge, Adrian Shubert and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Women Warriors and the Mobilization of Colonial Memory in the Nineteenth-Century United States Gina M. Martino A curious domestic tableau appears in Joel Dorman Steele’s 1885 textbook, A Brief History of the United States. The image, entitled “New England Kitchen Scene,” portrays a seventeenth-century woman sitting at her spinning wheel while minding a young child.1 Mother and child are the focus of the image, safely ensconced in a Victorian domestic sphere and separated from a pile of cut firewood and an axe on the floor by a wide fireplace and a bubbling cauldron. A translucent valance and a potted plant on the windowsill establish the space as civilized, cultivated, and feminine, signifying the triumph of colonialism to a nineteenth-century audience. But the artist of the engraving understood that the image required another element to effectively portray the colonial woman of the remembered past. And indeed, next to the potted plant— and partially obscured by the dainty window hanging—is the unmistakable shape of a blocky, early-modern musket within arm’s reach of the woman at the spinning wheel. -

Winter 2009 Issue 1

Friendships Newsletter of the Friendship Sloop Society Volume 21 FSS.ORG Winter 2009 Issue 1 Commodore’s Message Outside the first MAJOR snow storm of the winter (and of course visit with friends), we hope that you are starting 2008 is upon us. With many inches on the ground and many yet to make your plans now for what promises to be an exciting to come, thinking of summer and Friendships (both the boats and 3-days! the people) is a welcome break! It was wonderful to see so many faces at the Merry Wayne and Kirsten Cronin Manor Inn in South Portland for the Annual Meeting. There were many familiar faces and new faces. Unfortunately, Gail and Roger were not able to attend the meeting. As many of you are aware, Gail underwent surgery to remove a tumor in her brain in the beginning of November. While the process of 2009 Schedule of Events recovery is a long and challenging one, Gail and Roger are optimistic and hopeful that all will be well. As of this writing Spring Executive Committee Meeting they are spending their weeks in Boston for daily radiation treat- Saturday, April 4th ments and are returning to Belfast on the weekend. Your Peabody Essex Museum thoughts and well wishes are very much appreciated. Salem, MA It was with sadness that we heard the news of Jack New London Rendezvous & Cruise Vibber’s passing on December 9 th . Jack has been an integral part of the Friendship Sloop Society for many years. It was his hard Saturday, June 20th to Wednesday, June 24th work and dedication that began the New London Annual rendez- Southwest Harbor Rendezvous vous and cruise 20 years ago. -

Guide to the William A. Baker Collection

Guide to The William A. Baker Collection His Designs and Research Files 1925-1991 The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections of MIT Museum Kurt Hasselbalch and Kara Schneiderman © 1991 Massachusetts Institute of Technology T H E W I L L I A M A . B A K E R C O L L E C T I O N Papers, 1925-1991 First Donation Size: 36 document boxes Processed: October 1991 583 plans By: Kara Schneiderman 9 three-ring binders 3 photograph books 4 small boxes 3 oversized boxes 6 slide trays 1 3x5 card filing box Second Donation Size: 2 Paige boxes (99 folders) Processed: August 1992 20 scrapbooks By: Kara Schneiderman 1 box of memorabilia 1 portfolio 12 oversize photographs 2 slide trays Access The collection is unrestricted. Acquisition The materials from the first donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. The materials from the second donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by the estate of Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. Copyright Requests for permission to publish material or use plans from this collection should be discussed with the Curator of the Hart Nautical Collections. Processing Processing of this collection was made possible through a grant from Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. 2 Guide to The William A. Baker Collection T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Biographical Sketch ..............................................................................................................4 Scope and Content Note .......................................................................................................5 Series Listing -

September 2012.Indd

Volume 84, Number 09 September 2012 A Personal Note to the Members of SCYC Words are inadequate to express the gratitude webmaster” on my site at CaringBridge.org to help I feel for the tremendous amount of support I have get accurate information to you, Tim Gilmore, who received from all of you at SCYC. I have found out organized the life-saving blood drive for the Stanford that SCYC is truly a family that pulls together in tough Blood Bank that was held at SCYC, all the members times and I never expected the outpouring of kindness who urged me to go to the doctor when I showed up and generosity I have received from all of you. Janell at the club after sailing on 8/1 (which probably saved and I have simply been overwhelmed by your prayers, my life), Greg Haws for his encouragement and get- offers of help, encouragement and love. I especially ting the word out, everyone who drove all the way to want to thank Rob Schuyler, who has stepped in as Palo Alto to visit me in the hospital, everyone who Acting Commodore while I have been ill and has done wrote encouraging words on the CaringBridge site a superb job, De Schuyler, who has acted as a “co- and everyone who sent me cards and emails while I September 2012 Santa Cruz YaCht Club Spinnaker Vice Commodore Report Welcome home Dave! Our commodore, Dave Emberson, was diagnosed with leukemia this month and then made miraculous improvement during his treatment at Stanford Hospital. -

A New Breed of J-Class for a New Era of J-Class Racing

A NEW BREED OF J-CLASS FOR A NEW ERA OF J-CLASS RACING A NEW BREED OF J-CLASS FOR A NEW ERA OF J-CLASS RACING SHE IS THE largesT SUPER-J EVER TO BE LAUncHED wiTH OPTIMISED design for acHIEVing LINE HonoURS LIONHEART J–CLASS H1 A historY OF EXCELLENCE Thomas Sopwith (Sopwith Aviation Company) funded, Laying the Keel of Endeavour II in 1936. organised and helmed the yachts The men are ladling lead that will go Endeavour in 1934 (nearly winning) and into the 90-ton keel. Endeavour II in 1937. a history of excellence The most advanced and most powerful thoroughbred Only 10 J-Class yachts were designed and built J-Class yachts required enormous crews and, despite sailing yachts of their day, the J-Class was adopted for during the 1930’s. Several yachts of closely related expert attention to their technical details, still broke an the America’s Cup competition in 1928. The Class dimensions, mostly 23-Metre International Rule boats, astonishing number of masts. While they were in most itself dates back to the turn of the century when the were converted after their construction to meet the regards the most advanced and most powerful Universal Rule was adopted. This used a yacht’s rating rules of the J-Class but only the purpose-built thoroughbred sailing yachts ever to have been built, various dimensions to calculate an equivalent rating in Cup yachts could compete in the America’s Cup. the glorious J’s proved too extravagant for their own feet so vessels of varying lengths and sail size could good and most had limited sailing careers outside of compete against one another without the need to the America’s Cup - RANGER, whose 1937 cost was make allowances for time or distance sailed. -

The 50Th Race from Los Angeles to Honolulu Official Race Guide - $5.00 Transpac 2019 1 Contents Schedule of Events

THE 50TH RACE FROM LOS ANGELES TO HONOLULU OFFICIAL RACE GUIDE - $5.00 TRANSPAC 2019 1 CONTENTS Schedule of Events................................... 3 Welcome from the Governor of Hawaii.................. 8 Welcome from the Mayor of Honolulu .................. 9 Welcome from the Mayor of Long Beach................ 9 Welcome from the Transpacific Yacht Club Commodore ..... 10 Welcome from the Honolulu Committee Chair ........... 10 Welcome from the Sponsoring Yacht Clubs.............. 11 50th Transpac Preview ............................... 12 2019 Yacht Entries & Crews ........................... 14 Historic Transpac’s 50th Race Across the Pacific ....... 34 Transpac 2019 Perpetual Trophies..................... 37 Transpac 2019 Committees........................... 38 Mahalo List .......................................... 41 Diamond Head - Photo: Phil Uhl The 2017 Transpac ...................................43 The Ronald L. Burla Trophy............................46 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Final Aloha to Dale Nordin ............................48 June 15-16, 2019............................Safety at Sea Seminar 8 Bells Honor Roll ....................................49 0800 - 1600 Santa Monica Windjammers YC History Repeats - Transpac Greats Return for the 50th....50 Following the Transpac ...............................52 June 22-23, 2019.........Safety at Sea Seminar - Southwestern YC Barn Door Winners .................................. 54 Overall Winners..................................... 54 June 28, 2019 ...............Deadline for “As-Built” -

Thirty Chronicles

Thirty Chronicles The Collected Newsletters of the Herreshoff Marine Museum Numbers 1 to 30 (1979 - 2001) Scans by the Herreshoff Marine Museum and Maynard Bray Data Processing by Claas van der Linde Copyright © Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol, R.I. 2007 Contents No. 1 Spring 1979 Sprite Returns Home To Bristol [by Carlton J. Pinheiro] Thomas P. Brightman Obituary S Class Anniversary [by Halsey C. Herreshoff] NC-4 (aircraft) Anniversary [by Carlton J. Pinheiro] Old Jock Davidson Falls Overboard [by Clarence DeWolf Herreshoff] Museum Report – Spring 1979 [by Halsey C. Herreshoff] No. 2 Fall 1979 S Class Anniversary Race [by Halsey C. Herreshoff] Who Built The Yachts? [by Alice DeWolf Pardee] Recollections of the Herreshoffs [by Irving M. Johnson] 12 ½ Footer Donated [by Carlton J. Pinheiro] The “240” trip in 1906 [by A. Griswold Herreshoff] Mr. J.B., Though Blind, Directs His Chauffeur [by Clarence DeWolf Herreshoff] Columbia’s Topmast Returns [by Halsey C. Herreshoff] Railway Restored [by Nathanael G. Herreshoff III] No. 3 Spring 1980 Herreshoff Catamarans – Amaryllis [by Carlton J. Pinheiro] Enterprise Fiftieth Anniversary [by Nathanael G. Herreshoff III] Belisarius and Charles B. Rockwell [by Eleanor Rockwell Edelstein] N.G.H. Stops Vibration [by Clarence DeWolf Herreshoff] Recollections of Herreshoff Mfg. Co. [by Professor Evers Burtner] The Tender Nathanael [by Waldo Howland] Indian Donated [by George E. Lockwood] Memories of Captain Nat [by Pattie Munroe Catlow] No. 4 Fall 1980 Freedom Visits The Museum Colors Fly From Columbia’s Topmast Marjorie (Van Wickle Steam Yacht) [by Alice DeWolf Pardee] Captain Nat Ignores A Bit Of Horseplay [by Clarence DeWolf Herreshoff] J. -

J Class Model Yacht 1

January 1, 2011 J AMYA Class Specifications for the J Class Model Yacht 1. GENERAL 1.1. The J Class Model Yacht is a restricted design model yacht class. The purpose of these rules is to create a class that represents the spirit and beauty of the original J Class Yachts as they sailed in the 1930s. In that vein the hull and deck must be as close to the original as possible in shape unless otherwise specified in the rules 1.2. The boat, not the skipper is entered into events. Changing skippers during an event shall be permitted. 1.3. As necessary, interpretations of the Class Specifications may be requested from the Class Secretary. When issued, interpretations shall be communicated to all class members through the AMYA Quarterly magazine and the J Class web site. 1.3.1.Interpretations are to be temporary to allow class members to challenge them and call for a class vote using the annual AMYA ballot to accept or reject a specific interpretation. 1.3.2.Interpretations not challenged within one year of issue shall become permanent and incorporated in any subsequent revisions of these specifications. 1.4. Line Drawings 1.4.1.Line drawings in 1/16 scale by Serrao, Taglang, Chevalier, Maine Maritime Museum and M.I.T.are accepted by the class as being within the level of accuracy required. 1.4.2.Line drawings not listed above shall be submitted to the Class Secretary for approval. 2. HULL 2.1. Hulls shall be a scale model of the yachts listed in the chart in section 10.