Report on the Mining Pollution in New Caledonia TR:1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Health Situation

2013 Memento TheNew Health Caledonia Situation in 2013 www.dass.gouv.nc Main health facilities in New Caledonia* H Public hospitals Private clinics Provincial health facilities ARCHIPEL DES BELEP Secondary medical centers and facilities Specialised services Medical districts and medico-social centers Belep Ouégoa Poum Bondé LOYALTY ISLANDS Pouébo Mouli PROVINCE Koumac St-Joseph CHN P Thavoavianon** H Ouloup Kaala-Gomen Hienghène Hnacoam Hnaeu OUVÉA Touho Siloam Wedrumel Poindimié Dueulu NORTHERN Voh Nathalo PROVINCE H CHN R-D Nébayes** Chépénéhé Mou Koné Ponérihouen Hmeleck Wé Népoui Houaïlou LIFOU Tiga Rawa Poya Kouaoua Pénélo Bourail Canala La Roche Thio La Foa Tadine Wabao Hnawayatch MARÉ DumbéaNord SOUTHERN PROVINCE Païta Unia Dumbéa Yaté NOUMÉA Plum Goro Mont Dore Boulari Ile Ouen Family counselling center Gaston Bourret Hospital H Vao Multi purpose counselling Magenta Hospital H medical center (ESPAS-CMP) ILE DES PINS Raoul Follereau Center H School medical center Col de la Pirogue Center Health education and promotion H office Albert Bousquet Hospital H Islands Province medical center Mother and child protection centers and school medical centers Montravel (PMI) Baie des Citrons Clinic Kaméré (CMS) Anse Vata Clinic Saint-Quentin (CMS) Magnin Clinic * The health facilities and staff available to the people of New Caledonia are detailed in Chapter II: Health Services ** The Koumac and Poindimié (Northern Province) hospitals each have a medico-psychological unit attached to the Albert Bousquet ‘CSH’ (Specialised Hospital Centre) + Mother and Child Health Centres in Poindimié and Koumac 2013 Sommairecontents 04 Demographic characteristics ...................P. 04 Population Medical causes of death .........................P. 05 Medical causes of perinatal death ...........P. -

Public Private Partnership for Energy Production in NEW CALEDONIA

Public Private Partnership for Energy Production in NEW CALEDONIA Pierre Alla President CCE New-Caledonia PECC Conference November 17 / 18 Santiago de Chili SituationSituationSituation Réseau de Transport 150 kV : 471 km Réseau de Transport 33 kV : 566 km Réseaux de Distribution : 3 266 km BELEP Clients : 23 081 Waala Ouégoa Poum Pouébo OUVEA Koumac Hienghène Fayaoué Kaala-Gomen Touho LIFOU Poindimié We Voh Ponérihouen Koné Néaoua Pouembout Tu Kouaoua MARE Népoui Poya Canala Tadine Bourail Thio Moindou La Foa Boulouparis Païta Yaté Dumbéa Ducos Prony Doniambo ILE-des-PINS Mont-Dore NOUMEA Vao z 2005 EVOLUTION de la PUISSANCE MAXIMALE appelée par la Distribution Publique 110 107,2 MW 103,8 99,9 97,5 93,0 85,7 81,9 79,5 80,4 77,2 60 95-96 96-97 97-98 98-99 99-00 00-01 01-02 02-03 03-04 04-05 COURBES des VENTES d’ENERGIE 840 790 740 690 640 605 590 548 540 490 481 440 390 340 1994-1995 1995-1996 1996-1997 1997-1998 1998-1999 1999-2000 2000-2001 2001-2002 2002-2003 2003-2004 2004-2005 Prévision moyenne 5,0% Actualisation Prévision basse 3,0% Nickel in New Caledonia : Major Players INCO: Goro Greenfield Poum 0 50 100km project in the Tiabaghi N South FALCONBRIDGE Kouaoua Thio Koniambo greenfield GORO project in the NOUMEA Project North NEW SLN ERAMET AUSTRALIA CALEDONIA Operating a NEW ZEALAND smelting plant TASMANIA & 4 mines Goro Nickel Project - Project Summary Process plant production capacity : 60 000 tons of Nickel & 5 000 tons of Cobalt / year Mining production : 4 million tons / year Investment around US $1.8 billion Approximately -

Nouméa Isle of Pines LIFOU Maré

4 DREAM STOPOVERS Nouméa, Pacific French Riviera 6 excursions to nouméa Nouméa, the capital of New Caledonia, is • Amedee Lighthouse (island Cruise Map info a modern and vibrant city, with a blend daytrip) of French sophistication and Oceanian • Best of Noumea (scenic bus) atmosphere. A mix of architecture, gastronomy, shopping, and leisure • Duck Island / Lagoon activities between land and lagoon Snorkeling tours (snorkeling) that makes this city the true cultural • Noumea Aquarium (aquarium) and economic heart of the country. All • The green train / Tchou Tchou around, the beaches give visitors the Train feeling of being on the ‘Côte d’Azur’ (The • Tjibaou Cultural Center French Riviera). (museum) Lifou, Kanak Spirit 5 excursions to lifou Lifou, the main Loyalty Island, is • Cliffs of Jokin (lookout) characterised by the variety of its • Forest And Secret Grotto landscapes: white sandy beaches, (Melanesian tour) pristine waters, towering cliffs, huge • Jinek Bay Marine Reserve Pass new Caledonia caves… It is also famous for its vanilla plantations, its spectacular diving (snorkeling) spots and its preserved hiking paths. • Lifou’s Vanilla House As friendly as warm, Lifou’s inhabitants (museum) share their traditions and cultural • Luecila Beach And Scenic heritage with visitors. Drive (bays tour) Maré, welcome into the wild 3 excursions to maré Maré is the wildest and the highest • Excursion of the Takone island of the thrwee Loyalty Islands. Its factory (essential oils) outstanding and unspoilt sites echoes • Yejele transfer (beach tour) the traditions of its inhabitants. Carved out by the lagoon, Maré counts numerous • Eni tour (tribe welcome) caves and natural pools that attract fishes and turtles. -

Offre SUD, SUD EST Et LIFOU

NOUMÉA THIO - CANALA - KOUAOUA Offre SUD, SUD EST et LIFOU : LIGNE Nouméa - Canala Nouméa - Kouaoua Nouméa - Thio Nouméa - Thio Nouméa - Canala Nouméa - Kouaoua Nouméa - Canala Nouméa - Thio Nouméa - Canala Nouméa - Kouaoua Nouméa - Kouaoua Nouméa Thio Canala Kouaoua L-Ma-Me-J L-Ma-Me-J L-Ma-Me-J V V-D V-D D V Jours de circulation Sauf 23 septembre et Sauf 23 septembre et Sauf 23 septembre et Circule aussi jeudi 23 Circule aussi jeudi 23 S S S 1er novembre 1er novembre 1er novembre Circule aussi le jeudi Circule aussi lundi 1er Circule aussi jeudi 23 Jeudi 23 septembre et Jeudi 23 septembre Jeudi 23 septembre septembre et lundi septembre et lundi 23 septembre novembre septembre Arrêts lundi 1er novembre départ 14h et 16h. Le départ 17h. Le 1er 1er novembre 1er novembre départ 15h 1er nov départ 16h nov départ 16h30 NOUMEA - GARE 9:00 11:00 12:00 13:00 13:00 13:15 14:00 15:00 16:00 16:30 17:00 FRAISIERS* 9:19 11:19 12:19 13:19 13:19 13:34 14:19 15:19 16:19 16:49 17:19 PAÏTA NORD* 9:23 11:23 12:23 13:23 13:23 13:38 14:23 15:23 16:23 16:53 17:23 TONTOUTA VILLAGE* 9:38 11:38 12:38 13:38 13:38 13:53 14:38 15:38 16:38 17:08 17:38 TONTOUTA RIVIÈRE 9:43 11:43 12:43 13:43 13:43 13:58 14:43 15:43 16:43 17:13 17:43 TOMO VILLAGE 9:48 11:48 12:48 13:48 13:48 14:03 14:48 15:48 16:48 17:18 17:48 OUINANÉ 9:52 11:52 12:52 13:52 13:52 14:07 14:52 15:52 16:52 17:22 17:52 BOULOUPARIS VILLAGE 10:04 12:04 13:04 14:04 14:04 14:19 15:04 16:04 17:04 17:34 18:04 du NASSIRAH 13:10 14:10 16:10 1er juillet KOUA-ST MAURICE 13:21 14:21 16:21 KOUERGOA 13:24 14:24 16:24 -

Rubiaceae) Necessitated by the Polyphyly of Bikkia Reinw

Reinstatement of the endemic New Caledonian genus Thiollierea Montrouz. (Rubiaceae) necessitated by the polyphyly of Bikkia Reinw. as currently circumscribed Laure BARRABÉ Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, UMR AMAP, Laboratoire de Botanique et d’Écologie végétale appliquées, Herbarium NOU, BPA5, F-98848 Nouméa (New Caledonia) [email protected] Arnaud MOULY Université de Franche-Comté, UMR CNRS 6249 Chrono-Environnement, IUFM de Franche-Comté, 16 route de Gray, F-25030 Besançon (France) [email protected] Porter P. LOWRY II Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299 (USA) [email protected] and Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Département Systématique et Évolution, UMR 7205, case postale 39, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) [email protected] Jérôme MUNZINGER Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, UMR AMAP, Laboratoire de Botanique et d’Écologie végétale appliquées, Herbarium NOU, BPA5, F-98848 Nouméa (New Caledonia) [email protected] Barrabé L., Mouly A., Lowry II P. P. & Munzinger J. 2011. — Reinstatement of the endemic New Caledonian genus Thiollierea Montrouz. (Rubiaceae) necessitated by the polyphyly of Bikkia Reinw. as currently circumscribed. Adansonia, sér. 3, 33 (1) : 115-134. DOI: 10.5252/ a2011n1a8. ABSTRACT Th e genus Bikkia Reinw. as currently circumscribed comprises 20 species dis- tributed throughout the western Pacifi c Ocean, with a center of diversity in New Caledonia (11 species, all but one endemic). Two recent phylogenetic studies based respectively on molecular and morphological data have shown that Bikkia s.l. is polyphyletic, comprising two lineages: coastal Bikkia from the western Pacifi c (including the type species of the genus, B. -

New Caledonia Contains Useful Information for Yachtsmen Sailing Into the Largest Lagoon in the World

The first edition of the Stopover Handbook in New Caledonia contains useful information for yachtsmen sailing into the largest lagoon in the world. Welcome to the most spectacular sailing area, a French and Kanak stop over in the South Pacific region which offers quality services ans facilities, as well as vast and unspoiled cruising grounds. Welcome to this rich Melanesian region, a place of grear promise and friendliness. MY MY ARRIVAL STAY e e g g a a p 2 1p 1 the map 2 NOUMÉA 11 CENTRAL INSERT Since 2008, 60% of the Capital with 100,000 residents. Caledonian marine space Green and cosmopolitan town. Yachting services is listed on UNESCO's World Located in the South West of directory, Heritage list . An award for excel - the Main Island (Grande Terre), Nouméa maps, town L I D lence. A remarkable biodiversity the town allows an easy access centre and port area. / s a for humanity, with around thirty to close islets and the red lands d n a c strictly protected marine areas . of the Great South (Grand Sud). u D . S / S My arrival 5 P great South / T C Nouméa, main port of call in New IslE of PineS 17 N Caledonia. Green and red colours on land. ZOOM © Entry procedures, Tropical rainforest, mining bush, useful contacts, hot springs, waterfalls; Red soil cyclonic warning procedures, colouring feet in ochre. Inside the etc. lagoon, a variety of secluded e islands , white sand, crystal clear g a waters. A break in the Pine Island, p 9 MY a pearl of the region. -

Fate of Atmospheric Dust from Mining Activities in New Caledonia and the Impact on the Nickel Content of Lichen

Environmental Impact IV 489 FATE OF ATMOSPHERIC DUST FROM MINING ACTIVITIES IN NEW CALEDONIA AND THE IMPACT ON THE NICKEL CONTENT OF LICHEN ESTELLE ROTH1, EMMANUEL RIVIERE1, JEREMIE BURGALAT1, NADIA NGASSA1, YAYA DEMBELE1, MARIAM ZAITER1, ABDEL CHAKIR1, CAMILLE PASQUET2, RONAN PIGEAU2 & PEGGY GUNKEL-GRILLON2 1GSMA UMR CNRS 7331, University of Reims Champagne Ardenne, France ²ISEA, University of New Caledonia, Canada ABSTRACT Nickel mining in New Caledonia proceeds in open pit mining. Therefore, bare soil surfaces submitted to wind blow and mining operation (earthwork, excavating, transport, etc.) are a source of particulate matter. These phenomena produce essentially coarse metal rich dusts which undergo regional atmospheric transport. This study aims to determine how the mining activities can impact the environment and the population in conjunction with the presence of particles in the atmosphere via the wind transport. In this work, Koniambo (KNS) is the target mine, a new plant and mining site created in 2010 in the north of New Caledonia. Particle matter with diameter below 10 µm (PM10) was measured in three sites surrounding the KNS mine to follow the population exposition to particulate matter. Air mass trajectory modelling was carried out to identify the sources of high PM10 events (above 50 µg/m3) in these locations and to elaborate a density map of air mass trajectories. Five mines appeared to contribute more or less to rich PM10 air masses: KNS, Népoui, Poro, Kouaoua and Monéo. A density map of air mass trajectories originating from these mines showed areas where the lower atmosphere is potentially impacted by mining dust. As lichens are known for their air pollution bioindication properties, lichens were sampled in areas with high, medium and poor trajectory densities and their Ni and Ti content were analyzed. -

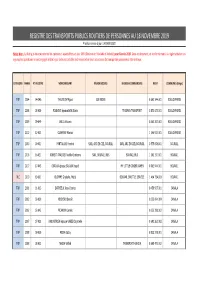

Tableau Recap Registre Trp-Vlc 20191118

REGISTRE DES TRANSPORTS PUBLICS ROUTIERS DE PERSONNES AU 18 NOVEMBRE 2019 Prochaine mise à jour : JANVIER 2020 Notez bien : Le listing ci-dessous recense les opérateurs ayant effectués leur DPA (Déclaration Préalable d'Activité) pour l'année 2019. Dans ce document, et conformément à la règlementation en vigueur, les opérateurs se sont engagés à être à jour de leurs contrôles techniques et de leurs assurances de transport de personnes à titre onéreux. CATEGORIE ANNEE N° REGISTRE NOM DIRIGEANT RAISON SOCIALE ENSEIGNE COMMERCIALE RIDET COMMUNES (Siège) TRP 2004 04-046 THEVEDIN Miguel GIE NEDEE 0 601 344.001 BOULOUPARIS TRP 2008 08-030 POANOUI épouse BOA Diana THIAMYA TRANSPORT 0 871 673.001 BOULOUPARIS TRP 2009 09-049 UHILA Victorio 0 560 367.003 BOULOUPARIS TRP 2012 12-003 GUIEYSSE Martial 1 046 523.001 BOULOUPARIS TRP 2000 00-031 PANTALONI Yannick SARL ARC EN CIEL BOURAIL SARL ARC EN CIEL BOURAIL 0 575 878.001 BOURAIL TRP 2016 16-021 ROBERT-TRAEGER Noëlle-Gratienne SARL BOURAIL BUS BOURAIL BUS 1 301 191.001 BOURAIL TRP 2017 17-043 DIROUA épouse SALAÜN Ingrid MY LITTLE GINGER GWEN 0 962 944.001 BOURAIL VLC 2019 19-001 BLOMME Graziella, Maité BOURAIL SHUTTLE SERVICE 1 414 754.001 BOURAIL TRP 2001 01-013 DATHIEUX Jean-Charles 0 459 917.001 CANALA TRP 2002 02-039 NECHERO Benoît 0 232 694.004 CANALA TRP 2002 02-042 PICANON Camillo 0 222 398.003 CANALA TRP 2007 07-038 KASOVIMOIN épouse VAKIE Chrystelle 0 690 263.002 CANALA TRP 2008 08-010 MIDJA Jacky 0 823 278.001 CANALA TRP 2008 08-032 NEDJA Wilfrid TRANSPORT KENDJA 0 608 471.002 CANALA TRP -

NOM De La Structure D'accueil Structure Porteuse De L'agrément

NOM de la structure d'accueil structure porteuse de l'agrément CEMEA ASSOCIATION TERRITORIALE DES CEMEA DE NOUVELLE CALEDONIE SCOUTS et GUIDES SCOUTS ET GUIDES DE FRANCE Association les Villages de Magenta UNION FRAN DES CENTRES DE VACANCES ET DE LOISIRS centre du service national DIRECTION DU SERVICE NATIONAL MIJPS MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Centre de Retraite de LA FOA MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Association sportive WETR MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD A.S. GAITCHA MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Centre d'Accueil Les Manguiers MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Centre Incendies Secours MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Direction de l'Environnement de la province MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES Sud DE LA PROVINCE SUD Ethnic music espoir MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Association des Artistes de Thio MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Parc Zoologique et Forestier MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Association ARTCOO MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD SEM M'WE ARA MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES ARENE DU SUD DE PAITA MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD ASSOCIATION BWARA TORTUES MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES MARINES DE LA PROVINCE SUD Association Mocamana L'Esprit Nature MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD MAIRIE DE LA FOA MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD MAIRIE DE YATE MISSION D'INSERTION DES JEUNES DE LA PROVINCE SUD MAIRIE -

Aller Côte Est Noumea Vers

ALLER CÔTE EST NOUMEA VERS.... NOUMEA TONTOUTA BOULOUPARIS LA FOA MOINDOU BOURAIL HOUAILOU MONEO PONERIHOUEN POINDIMIE TOUHO HIENGHENE NOUMEA / HIENGHENE 08H00 08H45 09H11 09H35 09H50 10H20 12H00 12H35 12H55 13H25 14H00 14H50 NOUMEA / POINDIMIE 10H30 11H15 11H40 12H05 12H20 12H50 14H30 15H05 15H20 15H55 16H15 NOUMEA / PONERIHOUEN 11H00 11H45 12H10 12H35 12H50 13H20 15H00 15H35 15H50 16H10 NOUMEA / HOUAÏLOU 12H00 12H45 13H10 13H35 13H50 14H20 16H00 LUNDI NOUMEA / THIO 13H00 13h40 14H05 ST MAURICE 14H25 KOUARE 14H40 ST MICHEL 14H50 NEPU 16H55 THIO 15H10 NOUMEA / CANALA 13H00 13h40 14h05 14H35 FARINO 14H40 PETIT COULI 15H00 HAOULI 15H41 LA CROUEN 15H50 CANALA VILL 16H05 NAKETI 16H25 NOUMEA / KOUAOUA 13H30 14H10 14H35 15H05 FARINO 15H25 KOH 16H05 MECHIN 16H20 KOUAOUA 16H35 HOUAÏLOU / HIENGHENE 08H00 08H35 08H55 09H30 10H00 10H50 NOUMEA / HIENGHENE 08H00 08H45 09H11 09H35 09H50 10H20 12H00 12H35 12H55 13H25 14H00 14H50 NOUMEA / POINDIMIE 10H30 11H15 11H40 12H05 12H20 12H50 14H30 15H05 15H20 15H55 16H15 NOUMEA / HOUAÏLOU 12H00 12H45 13H10 13H35 13H50 14H20 16H00 MARDI NOUMEA / THIO 13H00 13h40 14H05 ST MAURICE 14H25 KOUARE 14H40 ST MICHEL 14H50 NEPU 16H55 THIO 15H10 NOUMEA / CANALA 13H00 13h40 14h05 14H35 FARINO 14H40 PETIT COULI 15H00 HAOULI 15H41 LA CROUEN 15H50 CANALA VILL 16H05 NAKETI 16H25 NOUMEA / KOUAOUA 13H30 14H10 14H35 15H05 FARINO 15H25 KOH 16H05 MECHIN 16H20 KOUAOUA 16H35 HOUAÏLOU / HIENGHENE 08H00 08H35 08H55 09H30 10H00 10H50 NOUMEA / HIENGHENE 08H00 08H45 09H11 09H35 09H50 10H20 12H00 12H35 12H55 13H25 14H00 14H50 NOUMEA / POINDIMIE -

(G Viva ))) Et Principes D'organisation Sociale Dans La Vallée De La Kouaoua

Listes déclamatoires (G viva ))) et principes d’organisation sociale dans la vallée de la Kouaoua (Nouvelle-Calédonie) par . Patrick PILLON * ~ Ci M. Gabriel Diaïnon. 1. Introduction. la Kouaoua, plusieurs listes de (( viva)> différemment constituées. Chacune d’elles ne Les (( viva D sont des listes de noms, en peut dès lors être envisagée indépendamment majorité associCs deux à deux et qui sont des autres - ou pour le moins d’une certain déclamées lors des réunions cérémonielles. nombre d’entre elles. Tout (( viva D se construit sur des noms de Cet article s’attache à préciser le contenu lignages I auxquels peuvent être associés des des (( viva D, ainsi que les modalités de leurs sites d’habitat et de culture, des sommets constructions et de leurs différences de montagneux, ou des trous d’eau pour la pêche construction, par l’analyse comparative de en rivière. I1 forme un regroupement hiérar- quatre listes de (( viva,) de la vallée de la chisé distinct des autres regroupements, ou Kouaoua. Les (( viva )> apparaissent dès lors viva D, positionnés avant lui ou à sa suite. comme une donnée essentielle dans l’approche Une liste de (( viva )> a pour extension maxi- et dans la compréhension des principes d’or- male le pays (ou umwaciri>>), ensemble ganisation sociale dont ils constituent un élé- géographico-politique centré sur une vallée, ment fédérateur. ou sur une portion de zone côtière (Guiart, 1972 : 1133, 1136 ; Bensa, Rivierre, 1982 : 32 ; Métais, 1988). 2. La vallée de la Koiraoua : localisation et La composition de telles listes - semble-t-il langues pratiquées. par plusieurs individus -, renvoie pour l’es- sentiel aux hiérarchies statutaires générale- La région de Kouaoua est localisée au sud- ment reçues. -

The Impacts of Opencast Mining on the Rivers and Coasts of New Caledonia

THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY From the CHARTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY ARTICLE 1 act in accordance with the spirit of the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations and the Constitution PurpoS8s and structure of UNESCO and with the fundamental principles of 1. The United Nations University shall be an inter contemporary international law. national community of scholars, engaged in research, 6. The University shall have as a central objective post-graduate training and dissemination of knowledge of its research and training centres and programmes the in furtherance of the purposes and principles of the continuing growth of vigorous academic and scientific Charter of the United Nations. In achieving its stated communities everywhere and particularly in the develop· objectives, it shall function under the joint sponsorship ing countries, devoted to their vital needs in the fields of the United Nations and the United Nations Educa of learning and research within the framework of the tional, Scientific and Cultural Organization (hereinafter aims assigned to those centres and programmes in the referred to as UN ESCOl. through a central program present Charter. It shall endeavour to alleviate the intel ming and co-ordinating body and a network of research lectual isolation of persons in such communities in the and post·graduate training centres and programmes developing countries which might otherwise become located in the developed and developing countries. a reason for their moving to developed countries. 2. The University shall devote its work to research 7. In its post-graduate training the University shall into the pressing global problems of human survival, assist scholars, especially young scholars, to participate development and welfare that are the concern of the in research in order to increase their capability to con .