United States Foreign Assistance Oral History Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Manufacturing and Paper Shortages in the South, 1861-1865 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected]

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Special Topics Civil War Newspapers 2016 Paper Manufacturing and Paper Shortages in the South, 1861-1865 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cw_newstopics Recommended Citation Betts, ickV i, "Paper Manufacturing and Paper Shortages in the South, 1861-1865" (2016). Special Topics. Paper 18. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/790 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil War Newspapers at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Topics by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paper Manufacturing and Paper Shortages in the South, 1861-1865 ATHENS [GA] SOUTHERN WATCHMAN, May 1, 1861, p. 2, c. 1 Burning of the Pioneer Paper Mill. The paper mill three and a half miles from this place was totally consumed by fire on Wednesday morning last, together with all the paper and stock on hand. The origin of the fire, we believe, is considered doubtful. It may have been accidental, or it may have been the work of an incendiary. The loss is estimated at $16,000. There was no insurance. We believe it is the intention of the stockholders to rebuild--we hope so, at all events, as it is a great convenience to us to have our paper manufactured at home. BELLVILLE [TX] COUNTRYMAN, June 12, 1861, p. 2, c. 1 We are under the necessity of issuing but a half sheet this week. -

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 We Create Green Value Contents

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 We create green value Contents SUMMARY Key figures 6 Norske Skog - The big picture 7 CEO’s comments 8 Short stories 10 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT About Norske Skog’s operations 14 Stakeholder and materiality analysis 15 The sustainable development goals are an integral part of our strategy 16 Compliance 17 About the sustainability report 17 Sustainability Development Goals overview 20 Prioritised SDGs 22 Our response to the TCFD recommendations 34 How Norske Skog relates to the other SDGs 37 Key figures 50 GRI standards index 52 Independent Auditor’s assurance report 54 Design: BK.no / Print: BK.no Paper: Artic Volum white Editor: Carsten Dybevig Cover photo: Carsten Dybevig. All images are Norske Skog’s property and should not be used for other purposes without the consent of the communication department of Norske Skog Photo: Carsten Dybevig SUMMARY BACK TO CONTENTS > BACK TO CONTENTS > SUMMARY Key figures NOK MILLION (UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED) 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 mills in 5 countries INCOME STATEMENT 7 Total operating income 11 132 11 852 11 527 12 642 12 954 9 612 Skogn, Norway / Saugbrugs, Norway / Golbey, France / EBITDA* 818 1 081 701 1 032 1 938 736 Bruck, Austria / Boyer, Australia / Tasman, New Zealand / Operating earnings 19 -947 -1 702 926 2 398 -1 339 Nature’s Flame, New Zealand Profit/loss for the period -1 318 -972 -3 551 1 525 2 044 -1 884 Earnings per share (NOK)** -15.98 -11.78 -43.04 18.48 24.77 -22.84 CASH FLOW Net cash flow from operating activities 146 514 404 881 602 549 Net cash flow -

Annual Report Contents

2014 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS SUMMARY AND PRESENTATION 3 3 Key figures 3 Norske Skog 2014 4-5 CEO’s comments 6 Short stories 8-11 Board of Directors 12 Corporate Management 13 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 15 15 Norske Skog and local communities 19 Key figures - employees 2014 20 Paper production 22 Production capacity 22 Evaluation of our environmental performance 23 Sustainable raw materials 24 Energy consumption 26 Norske Skog’s greenhouse gas emissions 27 Our carbon footprint 28 Continuously improving our production processes 29 Water 31 Emissions to air and discharge to water 32 Mill figures 34 Independent auditor’s report 36 Environment and corporate social responsibility reporting 36 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 38 38 Organisation 40 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 42 42 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 50 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS NORSKE SKOGINDUSTRIER ASA 96 96 Notes to the financial statements 102 Independent auditor’s report 116 Declaration from the board of directors and CEO 118 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 120 120 Shares and share capital 124 SUMMARY AND PRESENTATION 126 126 Key figures related to shares 126 Articles of Association for Norske Skogindustrier ASA 128 Design and layout: pan2nedesign.no // Tone Strømberg Print: 07 Aurskog Paper: Norcote Trend 90 g/m2 - Norske Skog Photo and editor: Carsten Dybevig All images are Norske Skog’s property and should not be used for other purposes without the consent of the communication dept. of Norske Skog KEY FIGURES DEFINITIONS 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 INCOME STATEMENT -

Pulp and Paper Industry Is Implementing Iiot and Remote O&M

IIoT and Remote O&M in the Pulp & Paper Industry Webinar August 23, 2017 McIlvaine Company Northfield, IL Pulp & Paper Empowering IIoT with IIoW The pulp and paper industry is implementing IIoT and Remote O&M. As it does so it also needs to organize the wisdom of all the component suppliers so that IIoT will be empowered by IIoW. With IIoT it is possible to maximize the efficiency of an existing pump and drive. However, interaction with the valve and pump suppliers is needed so that they can make their products even better for each specific unique application. The suppliers of management systems need to better understand the capabilities of the component suppliers. The component suppliers need first to identify the specific opportunities and work toward providing each customer with the best products to fit his needs. With cloud based management systems utilizing data analytics there will be the equivalent of continuous white papers on each component. This knowledge will encourage purchasers to buy the best products rather than the ones with the lowest cost. Mcilvaine is providing a program built around specific forecasting of each component along with the broader analysis of the IIoT and Remote O&M opportunity . Table of Contents • IIoT Combust, Flow, Treat Markets • Pulp and Paper Industry Forecasts • Analysis of Largest Pulp and Paper Companies • International Paper • Stora Enso • Westrock • Weyerhauser • IIoT • Guide • Control • Measure • Components • Liquids • Gases • Powders Pulp and Paper IIoT Combust, Flow and Treat Markets Forecast of Sales to the Pulp and Sales of IIoT and Process Equipment to the Pulp and Paper Industry 2018 $ millions Paper Industry Product Total Product Revenues IIoT Impact The 8 automation companies have a direct IIoT All suppliers 8 companies All suppliers 8 companies market in pulp and paper of $90 million. -

Norske Skog Annual Report 2020 / Norske Skog 7 SUMMARY BACK to CONTENTS > BACK to CONTENTS > SUMMARY

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 We create green value Contents SUMMARY Key figures 6 Norske Skog - The big picture 7 CEO’s comments 8 Share information 10 Board of directors 12 Corporate management 13 Short stories 14 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT About Norske Skog’s operations 18 Stakeholder and materiality analysis 19 The sustainable development goals are an integral part of our strategy 20 Compliance 21 About the sustainability report 21 Sustainability Development Goals overview 24 Prioritised SDGs 26 Our response to the TCFD recommendations 38 How Norske Skog relates to the other SDGs 41 Key figures 54 GRI standards index 56 Independent Auditor’s assurance report 58 Corporate governance 60 Report of the board of directors 68 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 73 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 78 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS NORSKE SKOG ASA 119 Notes to the financial statements 124 Statement from the board of directors and the CEO 132 Independent auditor’s report 133 Alternative performance measures 137 Design: BK.no / Print: BK.no Paper: Artic Volum white Editor: Carsten Dybevig Cover photo: Adobe Stock. All images are Norske Skog’s property and should not be used for other purposes without the consent of the communication department of Norske Skog Photo: Carsten Dybevig SUMMARY BACK TO CONTENTS > BACK TO CONTENTS > SUMMARY Key figures NOK MILLION (UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED) 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 mills in 5 countries INCOME STATEMENT 7 Total operating income 11 132 11 852 11 527 12 642 12 954 9 612 Skogn, Norway / Saugbrugs, Norway / Golbey, -

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

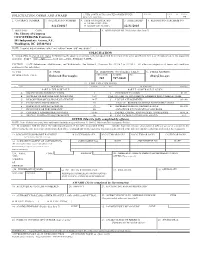

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

The Next Generation Lignoboost – Tailor-Maid Lignin Production for Different Lignin Bioproduct Markets

Published May 26, 2017 Next Generation LignoBoost The next generation LignoBoost – tailor-maid lignin production for different lignin bioproduct markets Executive Summary The list of end products that can be made from lignin ranges from fuel applications to carbon fibers and fine chemicals. As more lignin becomes available on the market one key question that needs to be addressed is, of course; What to do with the produced lignin? This paper describes highlights and important results from collaborations aimed to develop add-on processes that will produce lignin with a tailored specification. Pilot scale trials have been carried out producing a bio based carbon black from lignin. Carbon black can be used as reinforcement filler in rubber products. It was also shown that an odor free lignin could be produced by decreasing the guaiacol content in the lignin from 1.42 mg/kg to 0.04 mg/kg. The odor free lignin concept is ready for commercialization enabling production of a completely odor free bio- composite from lignin. © Valmet Page | 1 Published May 26, 2017 Next Generation LignoBoost Introduction Kraft lignin production at large scale is commercial and purified lignin is sold globally. Known trade names for lignin are BioChoice™ (Domtar) and BioPiva™ (UPM). Several pulp and paper manufacturers, such as Stora Enso, Domtar, UPM, Metsä Fibre, Suzano and Fibria, are changing their image to a broader bioproduct scope, including a production of lignin. When producing pulp according to the traditional kraft method the overall yield going from wood to pulp is about 50%. Part of the other 50% is used to produce new cooking chemicals, electricity and heat. -

Annual Report

Future on Paper NORSKE SKOG ANNUAL07 REPORT MAIN FINANCIAL FIGURES DEFINITIONS 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 Profit and loss account (NOK mill) Operating revenue 27 118 28 812 25 726 25 302 24 068 23 471 30 354 26 635 18 054 14 908 Gross operating earnings 1 8 395 3 932 4 220 4 303 4 686 5 198 8 419 6 599 3 818 3 103 Operating earnings 677 (2 527) 630 757 1 536 1 306 5 096 4 211 2 129 1 780 Earnings before financial expenses 2 785 (2 275) (51) 868 1 383 1 833 5 581 4 575 2 252 1 948 Earnings before taxation 235 (3 480) (1 004) 210 770 806 3 894 3 021 1 825 1 417 Earnings for the year (618) (2 809) (854) 621 402 1 162 2 494 1 958 300 1 020 Balance sheet (NOK mill) Fixed assets 29 307 37 577 43 740 36 861 39 219 38 197 45 417 43 717 18 828 17 586 Current assets 13 953 7 653 8 293 7 238 7 119 6 769 10 855 17 510 6 086 6 663 Total assets 43 260 45 230 52 033 44 099 46 338 44 966 56 272 61 227 24 914 24 249 Shareholder’s equity incl. minority int. 15 957 18 550 22 679 18 894 19 416 17 921 19 526 22 351 11 727 10 029 Long term debt 21 533 18 802 21 700 20 052 21 402 18 814 30 858 31 906 9 021 9 564 Current liabilities 5 770 7 878 7 654 5 153 5 520 6 210 5 888 6 970 4 166 4 656 Total liabilities and shareholder’s equity 43 260 45 230 52 033 44 099 46 338 42 945 56 272 61 227 24 914 24 249 Net interest bearing debt 16 409 17 321 19 063 16 871 17 759 18 204 22 820 20 535 7 618 7 082 Profitability Gross operating margin % 3 30.9 13.6 16.4 17.0 19.5 22.1 27.7 24.8 21.1 20.8 Net operating margin % 4 2.5 (8.8) 2.4 3.0 6.3 5.6 16.8 -

Improved Resource Utilization at a Kraft Pulp Mill

Improved Resource Utilization at a Kraft Pulp Mill A case study of Södra Cell Värö Master’s Thesis within the Sustainable Energy Systems program JOEL HEDLUND WILLIAM ULLGREN Department of Energy and Environment Division of Industrial Energy Systems and Technologies CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2015 MASTER’S THESIS Improved Resource Utilization at a Kraft Pulp Mill A case study of Södra Cell Värö Master’s Thesis within the Sustainable Energy Systems program JOEL HEDLUND WILLIAM ULLGREN SUPERVISORS: Roine Morin, Södra Karin Pettersson, Chalmers Elin Svensson, Chalmers EXAMINER: Karin Pettersson, Chalmers Department of Energy and Environment Division of Industrial Energy Systems and Technologies CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2015 Improved Resource Utilization at a Kraft Pulp Mill A case study of Södra Cell Värö Master’s Thesis within the Sustainable Energy Systems program JOEL HEDLUND WILLIAM ULLGREN © JOEL HEDLUND, WILLIAM ULLGREN, 2015 Department of Energy and Environment Division of Industrial Energy Systems and Technologies Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: The recovery boiler at the Södra Cell Värö pulp mill. Chalmers Reproservice Göteborg, Sweden 2015 Improved Resource Utilization at a Kraft Pulp Mill A case study of Södra Cell Värö Master’s Thesis in the Sustainable Energy Systems program JOEL HEDLUND WILLIAM ULLGREN Department of Energy and Environment Division of Industrial Energy Systems and Technologies Chalmers University of Technology ABSTRACT The Södra Cell Värö kraft pulp mill will during 2015 and 2016 be expanded to increase the pulp production capacity. The increased pulp production will generate an even larger amount of by-products and excess heat from the process, thus likely to increase the amount of unused resources compared with the current situation. -

Special Specifications

VAN WYCK EXPRESSWAY (VWE) CAPACITY AND ACCESS IMPROVEMENT TO JFK AIRPORT – CONTRACT 3 PIN X735.84, Contract D900053 DB CONTRACT DOCUMENTS REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS PART 8 SPECIAL SPECIFICATIONS Final August 20, 2021 New York State Department of Transportation This Part 8 – Special Specifications provides access to, and details the Project-specific requirements for the use of, the following documents: 1. NYSDOT Standard Specifications and Construction Materials 2. NYSDOT Engineering Information Issuances 3. NYSDOT Special Specifications. NYSDOT Standard Specifications and Construction Materials The Design-Builder shall use the NYSDOT Standard Specifications Construction Materials in coordination with Part 5 – Special Provisions. The NYSDOT Standard Specifications Construction Materials can be accessed at the following internet link: https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/engineering/specifications/busi-e-standards-usc. NYSDOT Engineering Information Issuances The Design-Builder shall use the relevant NYSDOT engineering information issuances, which include: 1. Engineering Instructions (EI); 2. Engineering Bulletins (EB); 3. Engineering Directives (ED). The above listed engineering information issuances can be accessed at the following internet link: https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/consultants/forms-publications-and- instructions/engineering-information-issuance-system NYSDOT Special Specifications The Design-Builder may use NYSDOT Special Specifications which are listed in the Electronic Pay Item Catalog (e-PIC) and which have received General Approval, and shall use any NYSDOT Special Specifications which are referenced in this Part 8 or elsewhere in the Contract Documents. Delete and ignore sections in the NYSDOT Special Specifications titled Method of Measurement and Basis of Payment from the NYSDOT Special Specifications. NYSDOT Special Specifications can be accessed at the following internet link: https://www.dot.ny.gov/main/business-center/engineering/specifications/special-specifications-us. -

Million Tons of Pulp, Paper and Lumber a Year

DEPENDABLE TO THE WE KEEP YOUR PRODUCTS MOVING CORE Design, Build, Operate, Finance & Maintain custom rail solutions. 2021 PULP, PAPER & Move and manage 3.7 million tons of pulp, paper and lumber a year. Complete turnkey solutions that cover all aspects of your mill. Industrial Rail Switching & Material Handling BIOECONOMY MAP Loading & Unloading of Railcars Cross Docking and Truck/Trailer Shunting Inventory Management Software System Best-In-Class Safety YUKON NORTHWEST TERRITORIES As a fourth-generation, family-owned company that’s been at the forefront of innovation for more than 70 years, we NUNAVUT know a thing or two about performance under pressure. And so do our core plugs. Learn how we can help you reduce loss and keep rolling. Visit souheganwood.com or call to discuss your needs at (603) 654-2311. BRITISH COLUMBIA [email protected] Toll-Free 1-866-989-5310 candorail.com ALBERTA Peace River n Taylor n Chetwynd (idle) Mackenzie (idle) Pub PULP 4.0 -7x3 inches.qxp_Mise en page 1 08.04.21 18:34 Pa PPC_Cando_MillMap21_CSA.indd 1 2021-05-28 7:23 AM Grande Prairie Slave Lake n s PPC_Souhegan_MillMap21_CSA.indd 1 2021-05-26 1:37 PM n s NEWFOUNDLAND Prince George n s Boyle n s & LABRADOR Whitecourt n l s Quesnel n Edmonton u s Meadow Lake n Hinton n s PULPING MANITOBA Corner Brook QUEBEC n l The Pas n s Powell River Kamloops n s Port Alberni Prince Albert (idle) Alma n l s n l n l s Baie-Comeau (idle) Dolbeau-Mistissani n s Port Mellon n l s Nanaimo LaTuque n l n s Vancouver s l s New Westminster l s Calgary l u Saguenay Crofton n l Richmond l St. -

Lignin Sulfonate Aquaculture – Aquatic Animals 1 2 Identification of Petitioned Substance 3 4 Chemical Name: 24 Phyto-Plus® Plant Stimulator – Baicor L.C

Lignin Sulfonate Aquaculture – Aquatic Animals 1 2 Identification of Petitioned Substance 3 4 Chemical Name: 24 Phyto-Plus® Plant Stimulator – Baicor L.C. 5 Lignin sulfonate 25 (OMRI, 2013) 6 26 SHADOW – LignoTech USA, Inc. (OMRI, 2013) 7 Other Names: 27 Orzan – ITT Rayonnier (Sugar and Spotts, 1986) 8 Lignosulfonate 9 Lignosulfuric acid CAS Numbers: 10 Lignosulfonic acid 28 8062-15-5 (lignin sulfonic acid) 11 LST 7 29 Lignosulfonate salts: 12 Ligninsulfonic acid 30 8061-51-6 (lignin sulfonic acid, sodium salt) 13 Poly(lignosulfonic acid) 31 9009-75-0 (sodium lignosulfonate) 32 8061-54-9 (magnesium lignosulfonate) 14 Protectol W 33 8061-53-8 (ammonium lignosulfonate) 15 Sulfite lignin 34 8061-52-7 (calcium lignosulfonate) 16 (NLM, 2013a) 35 (U.S. EPA, 2010a) 17 There are also various salts of lignin sulfonate 18 listed in the CAS Numbers section. Other Codes: 19 705707 (USEPA PC Code [U.S. EPA 2010b]) 20 Trade Names: 160226 (EPA Reference ID) ® 21 Lignosite – Georgia-Pacific (Georgia-Pacific 705705, 705708–705714 (U.S. EPA PC Code [U.S. 22 West, Inc., 2000) EPA, 2010b], various lignosulfonate salts) 23 BorrePlex – LignoTech USA, Inc. (OMRI, 2013) 1522 (CODEX Alimentarius Commission INS Number, calcium lignosulfonate) 36 37 Summary of Petitioned Use 38 39 The petitioner is requesting the addition of lignin sulfonate, a synthetic substance, to the National List of Allowed 40 and Prohibited Substances (hereafter referred to as the National List) for use as a synthetic substance allowed for 41 use in organic aquatic animal production. Lignin sulfonate currently is allowed for use as a synthetic substance in 42 organic crop production as a plant or soil amendment (chelating agent) and as a dust suppressant (7 CFR 43 205.601[j][4]), or as a floating agent in postharvest handling (7 CFR 205.601[l][1]).