Achieving "The Franchise": the Comcast-Nbc Universal Merger and the New Media Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comcast/NBC Universal Merger CASE STUDY

Comcast/NBC Universal Merger CASE STUDY Client In 2010, US cable company Comcast, a Multichannel Video Programming Distributor, and NBC Universal Inc (NBCU), a broadcast and for-pay programming provider, sought BLOOMBERG TV government approval for their proposed merger. During the merger review, Bates White Partner, Duke University professor, and former FCC chief economist Leslie M. Industry Marx submitted a report on behalf of Bloomberg TV, a video programming provider that had concerns about the merger impeding its effective competition in this market. COMMUNICATIONS Professor Marx suggested a number of remedies that were subsequently imposed on the merging parties by the FCC. Professor Marx showed how the integration between NBCU-owned CNBC, the dominant business channel, and Comcast, the dominant programming distributor in areas where demand for financial news is highest (e.g., New York and Chicago), would greatly increase the merged firm’s ability and incentive to anticompetitively foreclose Bloomberg TV from accessing end users (TV viewers and Internet users). After explaining the economic theories that led to a conclusion regarding competitive harm from the merger’s vertical integration, Professor Marx empirically measured the extent to which the merged firm could distort competition in the provision of financial news programming. Among other avenues, competitive harm could come from Comcast’s refusal to include Bloomberg TV in some of its programming bundles. This action would place Bloomberg TV in a tier with fewer subscribers, thereby disadvantaging Bloomberg TV and making end users more likely to turn to CNBC. Professor Marx also proposed conditions that could alleviate the anticipated competitive harms she had identified. -

Cablefax Dailytm Thursday — January 9, 2020 What the Industry Reads First Volume 31 / No

www.cablefaxdaily.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 Cablefax DailyTM Thursday — January 9, 2020 What the Industry Reads First Volume 31 / No. 006 Quick Bites: Quibi Not ‘Shrinking TV’ For Mobile Viewing In just over a year, short-form content streamer Quibi has been able to raise $1bln in funding while receiving the back- ing of major Hollywood studios, but are consumers ready to embrace the app? CEO Meg Whitman and founder Jeffrey Katzenberg used the company’s CES keynote Wednesday to dispel any consumer skepticism regarding Quibi, calling it the world’s first mobile-only premium entertainment platform. “Mobile phones are the most widely-distributed, democra- tized entertainment platform the world has ever seen,” Katzenberg said. The idea behind the platform is to deliver movie- quality experiences in quick bites (known as Quibis) for Millennial and Gen Z audiences that take advantage of all of the capabilities modern smartphones offer. To do so, Quibi had to tackle the usual challenges that come with mobile viewing, including the inability to watch content in both portrait and landscape modes. “It means creating a technology platform optimized for people on the go and giving them a great entertainment experience in those in-between moments,” Whit- man said. “We’re not shrinking TV onto phones. We’re creating something new.” Chief product officer Tom Conrad took to the stage to unveil Turnstyle, a new way to watch that allows viewers to move between a full-screen landscape mode and a full-screen portrait mode experience at any time. Conrad illustrated Turnstyle by showing the short film “Nest.” When the phone was held in portrait mode, viewers were able to see an intruder trying to break into a woman’s house through her Google Nest doorbell camera. -

Moments That Matter Executive Summary 2017 Corporate Social Responsibility Report (Covering 2016)

Moments that matter Executive Summary 2017 Corporate Social Responsibility Report (covering 2016) At Comcast NBCUniversal, we bring people closer to what matters. To the moments of purpose and passion that make our world a better place. About our commitment “Across all of our businesses “As a technology and broadband and platforms, we have a unique leader, it is our responsibility opportunity to connect people and obligation to do what to the moments that matter we can to help close the most to them.” digital divide.” BRIAN L. ROBERTS DAVID L. COHEN Chairman and CEO Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer From our place as one of the largest media, technology, and broadband companies in the world, we have the unique ability to help solve some of the most challenging social issues of our time. Our impact starts with our philanthropy and volunteerism, and it grows with our efforts to connect the unconnected and our ability to amplify the voices of today’s change- makers in our communities and within our own walls. That’s why we invest in digital inclusion, foster the brightest innovators and entrepreneurs, and spotlight young, diverse filmmakers. It’s why we hold up the microphone for community problem-solvers, and uphold and empower our own Comcast NBCUniversal family to make a lasting difference. Our influence and reach make it possible to create a positive impact every day. $500+ million In 2016, Comcast NBCUniversal provided more than $500 million in cash and in-kind contributions to local and national organizations that share our commitment to improving communities. -

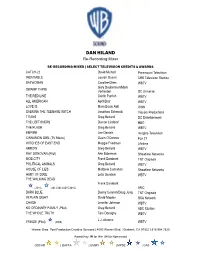

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

News and Documentary Emmy Winners 2020

NEWS RELEASE WINNERS IN TELEVISION NEWS PROGRAMMING FOR THE 41ST ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Katy Tur, MSNBC Anchor & NBC News Correspondent and Tony Dokoupil, “CBS This Morning” Co-Host, Anchor the First of Two Ceremonies NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 21, 2020 – Winners in Television News Programming for the 41th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy® Awards are being presented as two individual ceremonies this year: categories honoring the Television News Programming were presented tonight. Tomorrow evening, Tuesday, September 22nd, 2020 at 8 p.m. categories honoring Documentaries will be presented. Both ceremonies are live-streamed on our dedicated platform powered by Vimeo. “Tonight, we proudly honored the outstanding professionals that make up the Television News Programming categories of the 41st Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “As we continue to rise to the challenge of presenting a ‘live’ ceremony during Covid-19 with hosts, presenters and accepters all coming from their homes via the ‘virtual technology’ of the day, we continue to honor those that provide us with the necessary tools and information we need to make the crucial decisions that these challenging and unprecedented times call for.” All programming is available on the web at Watch.TheEmmys.TV and via The Emmys® apps for iOS, tvOS, Android, FireTV, and Roku (full list at apps.theemmys.tv). Tonight’s show and many other Emmy® Award events can be watched anytime, anywhere on this new platform. In addition to MSNBC Anchor and NBC. -

Philadelphia

Business TV Basic SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 2 601 KJWP Me TV 9 602 WTXF - Fox 20 614 WWSI - Telemundo 191 HSN 3 604 KYW - CBS 10 610 WCAU - NBC 21 607 QVC 615 WPPX ION 5 605 WPSG - CW 12 612 WHYY - PBS 22 609 HSN 853-902 Music Choice 6 606 WPVI - ABC Affiliate 13 613 WNJN PBS 24 603 WUVP - Univision Digital Music 7 617 WPHL 15 WLVT - PBS 25 Retro TV 8 608 RCN TV 19 WFMZ - Independent 190 QVC Business TV News SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 126 550 BBC America 305 650 CNN Custom 311 652 MSNBC 320 655 TWC 189 Discover Lehigh 306 656 CNN Headline News 315 653 Fox News Channel 322 Fusion Valley 310 651 CNBC 316 654 Fox Business 325 657 Bloomberg 301 C-SPAN Network Business TV Entertainment SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 101 619 BET 115 637 E! Entertainment 221 669 TV Land 333 660 Travel 105 620 A&E 116 658 truTV 222 641 Freeform 335 661 Discovery 106 621 Bravo 141 596 FXM 224 642 Food 340 662 History 107 622 TBS 142 667 American Movie 225 643 HGTV 345 663 TLC 108 623 TNT Classics 241 649 Nickelodeon 350 670 Nat Geo 109 624 USA 160 675 MTV 250 647 Disney 362 698 FXX 111 626 FX 165 676 VH1 256 Sprout 202 639 Lifetime Business TV Sports SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 363 681 ESPN 370 685 Comcast 376 YES National 389 690 NFL Network 364 682 ESPN 2 Sportsnet PA 380 575 CBS College Sports 391 695 MLB Network 365 683 ESPNEWS 372 686 Big Ten Network 381 694 The Golf Channel 392 697 NBA TV 368 680 ESPNU 374 MSG National 382 691 NBC Sports Network 375 689 Fox Sports 1 388 693 NHL Network Philadelphia Not all channels are available in all areas. -

Adelphia-Time Warner=Comcast Transaction Is Not in the Public I N Terest

Adelphia-Time Warner=Comcast Transaction is Not in the Public In terest CWA Presentation to FCC February 22,2006 Transaction is Not in the Public Interest . Anti-Competitive Impact . Negative Impact on Employees 2 Part 1. Anti-Competitive Impact . Cable companies have already used their market power to stifle video competition by limiting access to Regional Sports Networks or raising prices w The transaction will significantly increase market power in regions with RSNs Cable companies will have even more incentive and power to limit prospective Telco competitors 3 Cable Companies Have Utilized their Market Power over RSNs to Stifle Current DBS Competition . Exclusive Deals Comcast in Philadelphia has exclusive access to its RSN that carries Phillies, 76ers and Flyers Time Warner in Charlotte obtained exclusive access to an unaffiliated RSN that carried Bobcats games - even after this RSN went off the air Bobcat games are still only carried by Time Warner. 9 Increased Rates Comcast in Chicago bought the RSN and doubled the rate charged to DirecTV Time Warner in Cleveland has exclusive marketing deal with a new RSN that only carries Indians games but is charging competitors a rate that is almost the same as previously paid to carry Indians, Cavaliers, Reds and Blue Jackets games. Comcast and Time Warner own Sportsnet NY a new RSN that will carry Mets games but is charging higher prices than the YES network that carries Yankees games - even though the Mets have 1/3 the ratings The Impact of Cable’s Strategy: Less Competition Where cable companies have exclusive Regional Sports Networks, satellite penetration is half the national rate National Satellite Penetration 25.1 percent San Diego (Cox exclusive Padres) 12.8 percent . -

Spinco to Be Known As Greatland Connections Inc

Filed by Charter Communications Inc. Pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933 and deemed filed pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Subject Company: Charter Communications Inc. Commission File No. 001-33664 The following is a joint press release that was issued on September 3, 2014 by Charter Communications, Inc. and Comcast Corporation: SpinCo to be known as GreatLand Connections Inc. STAMFORD, Conn. and PHILADELPHIA - September 3, 2014 - Charter Communications, Inc. (NASDAQ:CHTR) and Comcast Corporation (NASDAQ: CMCSA, CMCSK) today announced the name of the new cable company that will be spun off from Comcast upon completion of the Comcast - Time Warner Cable merger and the Comcast - Charter transactions. The company referred to as “SpinCo” or “Midwest Cable LLC” will be known as GreatLand Connections Inc. “We are pleased to publicly announce the name of this exciting new company we are building,” said Michael Willner, President and Chief Executive Officer of GreatLand Connections. “The name GreatLand Connections pays homage to the rich history and striking geographies of the diverse communities in which the company will operate. It brings to mind our commitment to connecting people and businesses with terrific products and excellent service in the almost 1000 historic communities - large and small - across the 11 states we will serve.” GreatLand Connections Inc., a new, independent, publicly-traded company, will own and operate former Comcast systems serving approximately 2.5 million customers across the Midwest and Southeast. At its inception, it is expected to be the fifth largest cable company in the United States. -

Internet Essentials from Comcast Has Helped 10 Million Low-Income Americans Connect to the Tools and Resources They Need to Succeed in an Increasingly Digital World

Internet Essentials from Comcast has helped 10 million low-income Americans connect to the tools and resources they need to succeed in an increasingly digital world. TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Dave Watson .................................................................2 Digital Divide in the U.S. ...................................................................5 Program Timeline ............................................................................6 Program Retrospective .....................................................................8 Program Design ............................................................................ 10 Elements of Success ...................................................................... 16 Program Impact ................................................................................ 20 What’s Next ....................................................................................... 24 Commitment to Digital Equity ........................................................ 26 Student from Northeast High School III 1 Letter from Dave Watson $ about Comcast’s Commitment 7to 00Digital EquityM When we launched Internet Essentials 10 years ago, we began an ambitious journey to connect low-income Americans to the Internet. Thanks to the hard work and support of so many, Internet Essentials is now the largest and most comprehensive Internet adoption program in the country, connecting more than 10 million* people. Ten million people over 10 years is an exciting milestone, but it’s just the beginning -

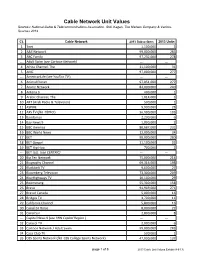

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, the Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, The Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013 Ct. Cable Network 2013 Subscribers 2013 Units 1 3net 1,100,000 3 2 A&E Network 99,000,000 283 3 ABC Family 97,232,000 278 --- Adult Swim (see Cartoon Network) --- --- 4 Africa Channel, The 11,100,000 31 5 AMC 97,000,000 277 --- AmericanLife (see YouToo TV ) --- --- 6 Animal Planet 97,051,000 277 7 Anime Network 84,000,000 240 8 Antena 3 400,000 1 9 Arabic Channel, The 1,014,000 3 10 ART (Arab Radio & Television) 500,000 1 11 ASPIRE 9,900,000 28 12 AXS TV (fka HDNet) 36,900,000 105 13 Bandamax 2,200,000 6 14 Bay News 9 1,000,000 2 15 BBC America 80,687,000 231 16 BBC World News 12,000,000 34 17 BET 98,000,000 280 18 BET Gospel 11,100,000 32 19 BET Hip Hop 700,000 2 --- BET Jazz (see CENTRIC) --- --- 20 Big Ten Network 75,000,000 214 21 Biography Channel 69,316,000 198 22 Blackbelt TV 9,600,000 27 23 Bloomberg Television 73,300,000 209 24 BlueHighways TV 10,100,000 29 25 Boomerang 55,300,000 158 26 Bravo 94,969,000 271 27 Bravo! Canada 5,800,000 16 28 Bridges TV 3,700,000 11 29 California Channel 5,800,000 16 30 Canal 24 Horas 8,000,000 22 31 Canal Sur 2,800,000 8 --- Capital News 9 (see YNN Capital Region ) --- --- 32 Caracol TV 2,000,000 6 33 Cartoon Network / Adult Swim 99,000,000 283 34 Casa Club TV 500,000 1 35 CBS Sports Network (fka CBS College Sports Network) 47,900,000 137 page 1 of 8 2013 Cable Unit Values Exhibit (4-9-13) Ct. -

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All Programming Subject to Change Without Notice

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All programming subject to change without notice. Visit www.mtco.com for current channel directory. ReStart TV available on ALL channels! Channel Directory Premium Channels A&E Network 525 Hallmark Drama 480 TLC 549 HBO ACC Network 472 Hallmark Movie & Mystery 586 TNT 521 HBO 600 AMC 571 HGTV 537 Travel Channel 573 HBO2 601 American Heroes Channel 527 History Channel 529 TruTV 522 HBO Comedy 603 Animal Planet 550 HSN 578 Turner Classic Movies 520 HBO Family 602 BBC America 572 IFC 544 TV Land 553 HBO Latino 606 BBC World 485 Inspiration 587 Universal Kids 466 HBO Signature 604 BET 575 Investigation Discovery 551 UNIVERSO 360 HBO Zone 605 BET Gospel 357 Jewelry TV 579 UP 321 BET Her 356 Lifetime Movie Network 538 USA Network 523 CINEMAX BET Jams 352 Lifetime Real Women 40 VH1 583 5StarMAX 613 BET Soul 355 Lifetime Television 539 Viceland 528 ActionMAX 609 Big Ten Network 564 LOGO 340 WBBM 2-CBS 2 501 Cinemax 607 Cinemáx 612 Big Ten Network Overflow 420 Marquee Network 560 WBBM Dabl 215 MoreMAX 608 Boomerang 462 MGM HD 479 WBBM Fave TV 216 MovieMAX 611 Bravo 541 Military History 339 WBBM Start TV 214 OuterMAX 614 Cartoon Network 530 Motor Trend Network 552 WCIU Decades TV 203 ThrillerMAX 610 CBS Sports Network 474 MSNBC 513 WCIU Heroes & Icons 227 CMT 584 MTV 581 WCIU MeTV 226 SHOWTIME CMT Music 358 MTV Classic 354 WCIU MeTV+ 228 FLIX 634 CNBC 512 MTV Live 489 WCIU The CW 10 506 Sho x BET 622 CNBC World 334 MTV Tr3s 350 WCIU The U 229 Sho2 (east) 628 CNN 510 MTV U 353 WCPX ION 38 507 Sho2 (west) 629 CNN Headline News -

NATAS Supplement.Qxd

A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT TO BROADCASTING & CABLE AND MULTICHANNEL NEWS The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences at 50 years,0 A golden past with A platinum future marriott marquis | new york october 20-21, 2005 5 THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Greetings From The President Executive Committee Dennis Swanson Peter O. Price Malachy Wienges Chairman of the Board President & CEO Treasurer Dear Colleagues, Janice Selinger Herb Granath Darryl Cohen As we look backwards to our founding and forward to our future, it is remarkable Secretary 1st Vice Chairman 2nd Vice Chairman how the legacy of our founders survives the decades. As we pause to read who Harold Crump Linda Giannecchini Ibra Morales composed Ed Sullivan’s “Committee of 100” which established the Academy in 1955, Chairman’s Chairman’s Chairman’s the names resonate with not just television personalities but prominent professionals Representative Representative Representative from theatre, film, radio, magazines and newspapers. Perhaps convergence was then Stanley S. Hubbard simply known as collaboration. Past Chairman of the Board The television art form was and is a work in progress, as words and pictures morph into new images, re-shaped by new technologies. The new, new thing in 1955 was television. But television in those times was something of an appliance—a box Board of Trustees in the living room. Families circled the wagons in front of that electronic fireplace Bill Becker Robert Gardner Paul Noble where Americans gathered nightly to hear pundits deliver the news or celebrities, fresh from vaudeville and Betsy Behrens Linda Giannecchini David Ratzlaff Mary Brenneman Alison Gibson Jerry Romano radio, entertain the family.