Benin 2011 Outlet Survey Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

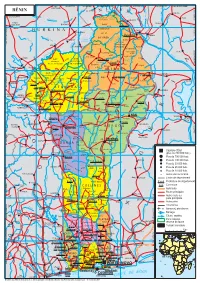

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

Rapport-Mémoire

1 PROGRAMME DE FORMATION AU DIPLOME D’ETUDE SUPERIEURE SPECIALISEE EN GESTION DES PROJETS ET DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL (DESS/GPDL) Rapport-Mémoire Le fnancement des collectivités locales par la coopération décentralisée : l’expérience du Fonds de Développement des Territoires du Programme de Promotion du Développement Local du département des Collines. i La Faculté des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion n’entend donner aucune approbation ni improbation aux opinions émises dans les mémoires. Elles doivent être considérées comme propres à leurs auteurs. Le mémoire est un essai d’application des méthodes et outils acquis au cours de la formation. Il ne saurait donc être considéré comme un travail achevé auquel l’Université conférerait un label de qualité qui l’engagerait. Ce travail est considéré a priori comme un document confdentiel qui ne saurait être diffusé qu’avec le double accord de son signataire et du PDL/Collines. ii TABLE DES MATIERES Pages REMERCIEMENTS .................................. ERREUR ! SIGNET NON DEFINI. ERREUR ! REFERENCE DE LIEN HYPERTEXTE NON VALIDE. CHAPITRE I – LE FINANCEMENT DES COLLECTIVITES LOCALES 6 I-1- LES SOURCES DE FINANCEMENT DES COLLECTIVITES LOCALES .................. 6 Erreur ! Référence de lien hypertexte non valide. I.1.1.1- Les ressources fscales locales .................................................... 7 Erreur ! Référence de lien hypertexte non valide. I.1.2- Ressources externes .......................................................................... 9 1.1.2.1- Transferts fnanciers de l’Etat ................................................... -

Rapport De L'etude Du Concept Sommaire Pour Le Projet De Construction De Salles De Classe Dans Les Ecoles Primaires (Phase 4)

Ministère de l’Enseignement No. Primaire, de l’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales République du Bénin RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE DU CONCEPT SOMMAIRE POUR LE PROJET DE CONSTRUCTION DE SALLES DE CLASSE DANS LES ECOLES PRIMAIRES (PHASE 4) EN REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Septembre 2007 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale DAIKEN SEKKEI, INC. GM JR 07-155 Ministère de l’Enseignement Primaire, de l’Alphabétisation et des Langues Nationales République du Bénin RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE DU CONCEPT SOMMAIRE POUR LE PROJET DE CONSTRUCTION DE SALLES DE CLASSE DANS LES ECOLES PRIMAIRES (PHASE 4) EN REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Septembre 2007 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale DAIKEN SEKKEI, INC. AVANT-PROPOS En réponse à la requête du Gouvernement de la République du Bénin, le Gouvernement du Japon a décidé d'exécuter par l'entremise de l'agence japonaise de coopération internationale (JICA) une étude du concept sommaire pour le projet de construction de salles de classes dans les écoles primaires (Phase 4). Du 17 février au 18 mars 2007, JICA a envoyé au Bénin, une mission. Après un échange de vues avec les autorités concernées du Gouvernement, la mission a effectué des études sur les sites du projet. Au retour de la mission au Japon, l'étude a été approfondie et un concept sommaire a été préparé. Afin de discuter du contenu du concept sommaire, une autre mission a été envoyée au Bénin du 18 au 31 août 2007. Par la suite, le rapport ci-joint a été complété. Je suis heureux de remettre ce rapport et je souhaite qu'il contribue à la promotion du projet et au renforcement des relations amicales entre nos deux pays. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Benin 2011 Outlet Survey Appendices

Appendices ACTs classified as quality assured Formulation Active ingredients Manufacturer Manufacture site Brand name Package size and strength Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Guilin Guilin, Guangxi, China Arsuamoon (1‐6yrs;7‐ 6;12;24 Amodiaquine 150mg Pharmaceutical Co. 13yrs; Adults) Ltd Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Ipca Laboratories Dadra and Nagar Haveli AS‐AQ Generic (Child; 6;12;24 Amodiaquine 153mg / Limited (U.T.), India Junior; Adult) 153.1mg Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Ipca Laboratories Dadra and Nagar Haveli Larimal (Child; Junior; 6;12;24 Amodiaquine 153mg / Limited (U.T.), India Adult) 153.1mg Artesunate + Tablets 25mg + Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Coarsucam 25mg/67.5mg 3 Amodiaquine 67.5mg Group Casablanca, Morocco (Infant) Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Coarsucam 50mg/135mg 3 Amodiaquine 135mg Group Casablanca, Morocco (Toddler) Artesunate + Tablets 100mg Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Coarsucam 3;6 Amodiaquine + 270mg Group Casablanca, Morocco 100mg/270mg (Child; Adult) Artesunate + Tablets 25mg + Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Winthrop 25mg/67.5mg 3 Amodiaquine 67.5mg Group Casablanca, Morocco (Infant) Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Winthrop 50mg/135mg 3 Amodiaquine 135mg Group Casablanca, Morocco (Toddler) Artesunate + Tablets 100mg Sanofi‐Aventis MAPHAR Laboratories, Winthrop 100mg/270mg 3;6 Amodiaquine + 270mg Group Casablanca, Morocco (Child; Adult) Artesunate + Tablets 50mg + Strides Arcolab Bangalore, India ACTipal (Madagascar) 3, 6, -

2021 Liste Des Candidats Mathi

MINISTERE DU TRAVAIL ET DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Fraternité - Justice - Travail ********** DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE DIRECTION CHARGEE DU RECRUTEMENT DES AGENTS DE L'ETAT Communiqué 002/MTFP/DC/SGM/DGFP/DRAE/STCD/SA du 26 mars 2021 CENTRE: LYCéE MATHIEU BOUKé LISTE D'AFFICHAGE DES CANDIDATS N° TABLE. NOM ET PRENOMS DATE ET LIEU DE NAISSANCE CORPS SALLE 0468-A16-1907219 Mlle ABDOU Affoussath 19/11/1997 à Parakou Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 16 0533-A18-1907218 Mlle ABDOU Rissikath 17/08/1988 à Lokossa Secrétaires des Services Administratifs(B3) A 18 0219-A08-1907213 M. ABDOULAYE Mohamadou Moctar 05/11/1987 à Niamey Techniciens Supérieurs de la Statistique A 8 0406-A14-1907219 Mlle ABIOLA Adéniran Adélèyè Taïbatou 30/06/1989 à Savè Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 14 0470-A16-1907219 M. ABISSIN Mahugnon Judicaël 04/04/1998 à Allahé Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 16 0281-A10-1907220 Mlle ABOUBOU ALIASSOU Silifatou 04/10/1990 à Ina Contrôleurs de l'Action Sociale (B1) A 10 0030-A01-1907189 M. ADAM Abdouramane 22/02/1988 à Penelan Administrateurs:Gestion des Marchés A 1 Publics 0233-A08-1907213 M. ADAM Ezéchiel 05/06/1997 à Parakou Techniciens Supérieurs de la Statistique A 8 0177-A06-1907203 M. ADAMOU Charif 20/11/1995 à Parakou Attachés des Services Financiers A 6 0448-A15-1907219 M. ADAMOU Kamarou 18/01/1996 à Kandi Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 15 0135-A05-1907203 M. ADAMOU Samadou 20/02/1989 à Nikki Attachés des Services Financiers A 5 0568-A19-1907216 Mlle ADAMOU Tawakalith 03/05/1991 à Lozin Techniciens d'Hygiène et d'Assainissement A 19 0584-A20-1907216 M. -

Ouessè Audit Fadec 2018

Audit de la gestion des ressources FADeC de l’exercice 2018 AUDIT DE LA GESTION DES RESSOURCES DU FONDS D’APPUI AU DEVELOPPEMENT DES COMMUNES (FADeC) AU TITRE DE L’EXERCICE 2018 COMMUNE DE OUESSE Etabli par : - AFANOTIN Benjamin-, (IGF/MEF) ; - EtabliDJIVO par Epiphane : -, (IGAA/MDGL). - Monsieur AFANOTIN Benjamin-, (IGF/MEF) ; - Monsieur DJIVO Epiphane-, (IGAA/MDGL). Septembre 2019 Septembre 2019 i Commune de Ouessè Audit de la gestion des ressources FADeC de l’exercice 2018 TABLE DES MATIERES INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1 ETAT DES TRANSFERTS FADEC, GESTION ET NIVEAU DE CONSOMMATION DES CREDITS .............. 3 1.1 SITUATION D’EXECUTION DES TRANSFERTS FADEC ......................................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Les crédits de transfert mobilisés par la commune au titre de la gestion ......................................... 3 1.1.2 Situation de l’emploi des crédits disponibles ..................................................................................... 6 1.1.3 Niveau d’exécution financière des ressources de transfert ............................................................. 19 1.1.4 Marchés non soldés au 31 Décembre 2018 ..................................................................................... 23 1.1.5 Traçabilité des ressources et dépenses FADeC dans les comptes et respect de la note de cadrage budgétaire, qualité du compte administratif ............................................................................................... -

BENIN-2 Cle0aea97-1.Pdf

1° vers vers BOTOU 2° vers NIAMEY vers BIRNIN-GAOURÉ vers DOSSO v. DIOUNDIOU vers SOKOTO vers BIRNIN KEBBI KANTCHARI D 4° G vers SOKOTO vers GUSAU vers KONTAGORA I E a BÉNIN N l LA TAPOA N R l Pékinga I o G l KALGO ER M Rapides a vers BOGANDÉ o Gorges de de u JE r GA Ta Barou i poa la Mékrou KOULOU Kompa FADA- BUNZA NGOURMA DIAPAGA PARC 276 Karimama 12° 12° NATIONAL S o B U R K I N A GAYA k o TANSARGA t U DU W o O R Malanville KAMBA K Ka I bin S D É DU NIGER o ul o M k R G in u a O Garou g bo LOGOBOU Chutes p Guéné o do K IB u u de Koudou L 161 go A ZONE vers OUAGADOUGOU a ti r Kandéro CYNÉGÉTIQUE ARLI u o KOMBONGOU DE DJONA Kassa K Goungoun S o t Donou Béni a KOKO RI Founougo 309 JA a N D 324 r IG N a E E Kérémou Angaradébou W R P u Sein PAMA o PARC 423 ZONE r Cascades k Banikoara NATIONAL CYNÉGÉTIQUE é de Sosso A A M Rapides Kandi DE LA PENDJARI DE L'ATAKORA Saa R Goumon Lougou O Donwari u O 304 KOMPIENGA a Porga l é M K i r A L I B O R I 11° a a ti A j 11° g abi d Gbéssé o ZONE Y T n Firou Borodarou 124 u Batia e Boukoubrou ouli A P B KONKWESSO CYNÉGÉTIQUE ' Ségbana L Gogounou MANDOURI DE LA Kérou Bagou Dassari Tanougou Nassoukou Sokotindji PENDJARI è Gouandé Cascades Brignamaro Libant ROFIA Tiélé Ede Tanougou I NAKI-EST Kédékou Sori Matéri D 513 ri Sota bo li vers DAPAONG R Monrou Tanguiéta A T A K O A A é E Guilmaro n O Toukountouna i KARENGI TI s Basso N è s u Gbéroubou Gnémasson a Î o u è è è É S k r T SANSANN - g Kouarfa o Gawézi GANDO Kobli A a r Gamia MANGO Datori m Kouandé é Dounkassa BABANA NAMONI H u u Manta o o Guéssébani -

En Téléchargeant Ce Document, Vous Souscrivez Aux Conditions D’Utilisation Du Fonds Gregory-Piché

En téléchargeant ce document, vous souscrivez aux conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché. Les fichiers disponibles au Fonds Gregory-Piché ont été numérisés à partir de documents imprimés et de microfiches dont la qualité d’impression et l’état de conservation sont très variables. Les fichiers sont fournis à l’état brut et aucune garantie quant à la validité ou la complétude des informations qu’ils contiennent n’est offerte. En diffusant gratuitement ces documents, dont la grande majorité sont quasi introuvables dans une forme autre que le format numérique suggéré ici, le Fonds Gregory-Piché souhaite rendre service à la communauté des scientifiques intéressés aux questions démographiques des pays de la Francophonie, principalement des pays africains et ce, en évitant, autant que possible, de porter préjudice aux droits patrimoniaux des auteurs. Nous recommandons fortement aux usagers de citer adéquatement les ouvrages diffusés via le fonds documentaire numérique Gregory- Piché, en rendant crédit, en tout premier lieu, aux auteurs des documents. Pour référencer ce document, veuillez simplement utiliser la notice bibliographique standard du document original. Les opinions exprimées par les auteurs n’engagent que ceux-ci et ne représentent pas nécessairement les opinions de l’ODSEF. La liste des pays, ainsi que les intitulés retenus pour chacun d'eux, n'implique l'expression d'aucune opinion de la part de l’ODSEF quant au statut de ces pays et territoires ni quant à leurs frontières. Ce fichier a été produit par l’équipe des projets numériques de la Bibliothèque de l’Université Laval. Le contenu des documents, l’organisation du mode de diffusion et les conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché peuvent être modifiés sans préavis. -

Cahier Des Villages Et Quartiers De Ville Du Departement Des Collines (Rgph-4, 2013)

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN &&&&&&&&&& MINISTERE DU PLAN ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT &&&&&&&&&& INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE L’ANALYSE ECONOMIQUE (INSAE) &&&&&&&&&& CAHIER DES VILLAGES ET QUARTIERS DE VILLE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES (RGPH-4, 2013) Août 2016 REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN &&&&&&&&&& MINISTERE DU PLAN ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE L’ANALYSE ECONOMIQUE (INSAE) &&&&&&&&&& CAHIER DES VILLAGES ET QUARTIERS DE VILLE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES Août 2016 Prescrit par relevé N°09/PR/SGG/REL du 17 mars 2011, la quatrième édition du Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitation (RGPH-4) du Bénin s’est déroulée sur toute l’étendue du territoire national en mai 2013. Plusieurs activités ont concouru à sa réalisation, parmi lesquelles la cartographie censitaire. En effet la cartographie censitaire à l’appui du recensement a consisté à découper tout le territoire national en de petites portions appelées Zones de Dénombrement (ZD). Au cours de la cartographie, des informations ont été collectées sur la disponibilité ou non des infrastructures de santé, d’éducation, d’adduction d’eau etc…dans les villages/quartiers de ville. Le présent document donne des informations détaillées jusqu’au niveau des villages et quartiers de ville, par arrondissements et communes. Il renseigne sur les effectifs de population, le nombre de ménages, la taille moyenne des ménages, la population agricole, les effectifs de population de certains groupes d’âges utiles spécifiques et des informations sur la disponibilité des infrastructures communautaires. Il convient de souligner que le point fait sur les centres de santé et les écoles n’intègre pas les centres de santé privés, et les confessionnels, ainsi que les écoles privées ou de type confessionnel. -

Governance and Economic Performance, Delegated Public Drinking Water Services in the Municipality of Dassa-Zoume (Benin)

International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI) | Volume VII, Issue XI, November 2020 | ISSN 2321–2705 Governance and Economic Performance, Delegated Public Drinking Water Services in the Municipality Of Dassa-Zoume (Benin) Rene Ayeman Zodekon1, Ernest Amoussou1-2 & Leocadie Odoulami3 1,3Pierre PAGNEY Laboratory, Climate, Water, Ecosystem and Development (LACEEDE) / DGAT / FLASH / University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC) BP 526 Cotonou, Republic of Benin (West Africa) 2-Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Parakou, Parakou, Benin, Abstract: The delegation of management of water services is part risks inherent in the management of the service while of an alternative logic to the community management model of retaining its prerogatives as a public authority. drinking water supply networks. This method of managing water services is faced with numerous irregularities in the municipality In the municipality of Dassa-Zoumé, the delegation of of Dassa-Zoumé. This research analyzes the mode of governance management of water supply networks characterized by the by delegation of water services with a view to determining its establishment of a contractual relationship between a performance indicators. delegating authority and a delegated manager in order to The method used is based on data collection from 50 delegatees deliver a water service from these facilities. (public and private), 50 households from user associations and 10 Common in urban hydraulics, this approach was introduced in resource persons. The data collected was processed and the rural hydraulics in the early 2000s as an alternative to results obtained were analyzed with the SWOT model. community management, the performance of which, after Results show that 298 FPMH and 6 AEV are delegated to public twenty years of practice, has generally not been up to the and private operators. -

Liste Des Entreprises CCIB - 2015

Liste des Entreprises CCIB - 2015 N°RC Raisons Sociales Adresses Complètes Activités Nom Prénoms ContactIFU n° CatégorieSecteur NationalitéRégion COTONOU- GBENA- C/N° 227 COMMERCE ASSANI EPOUSE ETABLISSE 08-A-5047 DU 30/09/2008 "A.2.S." 06 BP 1294 PK 3 - TEL: 95-40-59- ACHAT ET VENTE PRODUITS COSMETIQUES ET COMMERCE GENERAL BENINOISE Cotonou OSSENI ALMEÎNI MENT 42 ARTICLES DE MAROQUINERIE COTONOU - AIDJEDO 3 - C/N° COMMERCE IMBERT JEANNETTE ETABLISSE ACHAT ET VENTE DE 08-A-3558 DU 25/02/2008 "ASIR" 290 F 3.201.200.247.219 BENINOISE Cotonou ACHAT ET VENTE DE TISSUS- ASSIBA MENT TISSUS 03 BP 0400 - TEL: 97-48-14-80 COTONOU- DEGAKON - C/N° SERVICE ASSURANCES, AGENTS ILOT 754 DEGAKON COMMERCIALISATION DE PRODUITS D'ASSURANCE ET OLAOGOU FAÏZATH ETABLISSE DE PUB ET D'AFFAIRES, 09-A-6557 DU 30/03/2009 "KMN-ASSUR" 3,2009E+12 BENINOISE Cotonou 01 BP 5319 COTONOU - TEL: 97- DIVERSES PRESTATIONS DE SERVICES- SYLVIA MENT AGENTS IMMOBILIERS 77-00-23 INTERMEDIATION ET CONSEIL EN ASSURANCE- ET DE COMMERCE COMMERCE COTONOU- AGLA- C/N° 3098 ETABLISSE COMMERCIALISATION 11-A-11878 DU 17/02/2011 "LA MANNE DOREE" ACHAT ET VENTE DE PRODUITS FORESTIERS- EKE AFIA MONIQUE 3201100364817 BENINOISE Cotonou 08 BP 1168 - TEL: 96-06-07-80 MENT PRODUITS FORESTIERS ALIMENTAIRES-BOISSONS-BOULANGERIE-PATISSERIE COTONOU GBEDAGBA C/N° SERVICE 1327 - J.04 SAMA MICHEL ETABLISSE BUREAUX D'ETUDES - 07-A-2184 DU 05/11/2009 "URBA-TROPIQUES" PRESTATIONS DE SERVICES EN URBANISME ET 2.977.421.186.134 BENINOISE Cotonou 01 BP 4387 - TEL: 21-35-18-21 / RODRIGUE MENT INGENIERIE ARCHITECTURE