A Study of the Compositional Methods of Jerry Bergonzi, Miguel Zenón, and Donny Mccaslin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Jazz Series Concert Features Saxophonist Donny Mccaslin Lawrence University

Lawrence University Lux Press Releases Communications 2-15-2011 Jazz Series Concert Features Saxophonist Donny McCaslin Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: http://lux.lawrence.edu/pressreleases © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Lawrence University, "Jazz Series Concert Features Saxophonist Donny McCaslin" (2011). Press Releases. Paper 438. http://lux.lawrence.edu/pressreleases/438 This Press Release is brought to you for free and open access by the Communications at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Press Releases by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jazz Series Concert Features Saxophonist Donny McCaslin Posted on: February 15th, 2011 by Rick Peterson Critically acclaimed saxophonist and composer Donny McCaslin showcases his “roof-raising” talents Friday, February 25 at 8 p.m. at the Lawrence Memorial Chapel as part of the 2010-11 Lawrence University Jazz Series. McCaslin will be joined by the Lawrence Brass. Donny McCaslin “Donny McCaslin definitely belongs in any discussion of top jazz saxophonists like Chris Potter and others,” said tubist Marty Erickson, a member of the Lawrence Brass. “He is very comfortable playing hard funk and a kind of high-energy post- bebop, but he also can render a ballad with the best of them.” One of the pieces The Lawrence Brass will perform with McCaslin will be from his 2009 CD “Declarations,” which was ranked 12th on a list of favorite jazz CDs of 2009 by the website The Jazz Spectrum. Described by Jazz Times as a “versatile” musician who plays with a “fluidity and grace,” McCaslin first picked up the tenor saxophone at the age of 12 and!participated in the prestigious Monterey Jazz Festival’s California All-Star band while still in high school. -

The Hot Club of Baltimore: Baltimore Discovers the Spirit of Django

FEB/MARCH 2014 The Hot Club of Baltimore: Baltimore Discovers the Spirit of Django . 1 Cold Spring Jazz Quartet – Night Songs: The Music of Film Noir . 3 BALTIMORE JAZZ ALLIANCE An Interview with Donny McCaslin . 4 Warren Wolf, Christian McBride and Friends . 6 Jazz Jam Sessions . 10 BJA Member Notes, Products and Discounts . 10 Ad Rates and Member Sign-up Form . 11 VOLUME XI ISSUE II THE BJA NEWSLETTER WWW.BALTIMOREJAZZ.COM Baltimore Discovers the Spirit of Django The Hot Club A cold start to February’s Monday night ously sat in. On this particular night a Gypsy Jazz Jam didn’t prevent Balti - blend of accordion, violin, harmonica more’s Djangophiles from flocking to and four guitars kicked off the jam. of Baltimore Liam Flynn’s Ale House, an atmospheric, Swinging into action in the middle of welcoming, bare-bones pub on W. North the room, seated in the round and soloing Avenue, Baltimore. For nearly a year, in rotation, the musicians started with the under the leadership of guitarist Michael jazz standard “Coquette.” Harris’s open - Joseph Harris, whom many will know ing solo embellished the song with the through his band Bossalingo, the Mon - arpeggios and flourishes that typify the day night jam has been picking up acco - Django style. Arefin’s guitar picked up the lades and winning over fans. City Paper theme, building the rhythmic energy with recently declared the jam to be Best Mon - a more chordal solo before handing off to day Night in Baltimore. the liquid Wes Montgomery-style runs of Musicians from as far away as Jim Tisdall. -

Doctorella-Faz

SEITE 12 · MONTAG, 14. NOVEMBER 2016 · NR. 266 Musik FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG Auch das noch Brillant, frisch, mit einem Schuss Lachen Als der Produzent Walter Legge 1946 in Wien für seine Firma „His Master’s Voice“ vielversprechende Künstler such- te, fand er eine junge Sängerin, die nach kurzer Zeit nicht nur seine Ehefrau, son- dern auch „Her Master’s Voice“ wurde: Eli- sabeth Schwarzkopf. Sie gab am 23. Ok- tober 1946 im Brahmssaal des Wiener Mu- sikvereins ihr Platten-Debüt: mit der Mar- tern-Arie der Konstanze aus Mozarts „Entführung“. Am Pult stand ein zweiter Star in spe: Herbert von Karajan. Es war die erste von knapp einhundert 78er Plat- ten aus der Zeit vor der Langspielplatte, die jetzt, erstmals vollständig veröffent- licht, die Begegnung mit einer Stimme er- möglichen, deren Klang Legge als ,,brilli- ant, fresh and shot with laughter“ be- schrieb (The Complete 78 RPM Recor- dings 1946–1952, Warner). Wie die bra- vourös gesungene Martern-Arie sind auch die Aufnahmen von Bachs „Jauchzet Gott“ (mit einem stupenden Trompeten- solo), Händels ,,L’allegro, il pensiero“ (ei- nem ebenso stupenden Flötensolo), Mo- zarts „L’amerò, sarò costante“ (mit einer sublimen Kadenz) Zeugnisse feinster Bel- canto-Kunst. Der Zauber ihrer mit vielen Farben malenden Stimme verdoppelt sich im Zusammenklang mit dem Samtsopran von Irmgard Seefried im Abendsegen aus „Hänsel und Gretel“. In den Liedern – Dowland, Arne, Schubert, Schumann, Der Witz am Blitz ist das Licht im Gesicht: Sandra (links) und Kerstin Grether von Doctorella wissen ganz genau, wie Hingucken aussieht. Foto Bohemian Strawberry Brahms, Wolf und Nikolai Medtner – ist die Empfindungstiefe der Jugend zu spü- ren und nichts von den Detailaffektatio- nen der ,reifen‘ Diva. -

Students and Faculty at the KU School of Music Have Been As Busy As

Students and faculty at the KU School of Music have been as busy as ever this February! We’ve included in this QuickNotes a variety of information about upcoming events as well as updates on our student and faculty achievements. As always, please visit us at http://music.ku.edu for a complete list of news and events! The renowned wind quintet, Imani Winds, will be in residency March 14-16, 2012, at the University of Kansas to present various master classes, presentations and performances. The Imani Winds Residency is sponsored by Reach Out Kansas, Inc.; The Law Offices of Smithyman & Zakoura Chartered; and the Zakoura Family Fund. Events open to the public include: • Wednesday, March 14: 1:00pm: Various Studio Classes, Murphy Hall • Wednesday, March 14: 5:30-8:30pm: Imani Winds to participate in chamber music coaching sessions, Swarthout Recital Hall • Thursday, March 15: 10am-“Thinking Outside the Box” presentation by Imani Winds, Swarthout Recital Hall • Thursday, March 15: 3:30-5pm: Coaching with the KU Symphony Orchestra, Murphy Hall, Room 118 • Friday, March 16: 9-10:30am: Imani Winds “Informance” in Swarthout Recital Hall • Friday, March 16: 11:00am: Presentation: The Business of Music, Swarthout Recital Hall The KU School of Music is pleased to present the 35th Annual KU Jazz Festival on March 2-3, 2012, featuring notable guest artists Donny McCaslin (saxophone) and Alex Sipiagin (trumpet). Evening concerts are open to the general public. On Friday, March 2 at 7:30 p.m. at Lawrence High School Auditorium, saxophonist Donny McCaslin will be featured with the KU Jazz Festival All-Star Big Band. -

We Offer Thanks to the Artists Who've Played the Nighttown Stage

www.nighttowncleveland.com Brendan Ring, Proprietor Jim Wadsworth, JWP Productions, Music Director We offer thanks to the artists who’ve played the Nighttown stage. Aaron Diehl Alex Ligertwood Amina Figarova Anne E. DeChant Aaron Goldberg Alex Skolnick Anat Cohen Annie Raines Aaron Kleinstub Alexis Cole Andrea Beaton Annie Sellick Aaron Weinstein Ali Ryerson Andrea Capozzoli Anthony Molinaro Abalone Dots Alisdair Fraser Andreas Kapsalis Antoine Dunn Abe LaMarca Ahmad Jamal ! Basia ! Benny Golson ! Bob James ! Brooker T. Jones Archie McElrath Brian Auger ! Count Basie Orchestra ! Dick Cavett ! Dick Gregory Adam Makowicz Arnold Lee Esperanza Spaulding ! Hugh Masekela ! Jane Monheit ! J.D. Souther Adam Niewood Jean Luc Ponty ! Jimmy Smith ! Joe Sample ! Joao Donato Arnold McCuller Manhattan TransFer ! Maynard Ferguson ! McCoy Tyner Adrian Legg Mort Sahl ! Peter Yarrow ! Stanley Clarke ! Stevie Wonder Arto Jarvela/Kaivama Toots Thielemans Adrienne Hindmarsh Arturo O’Farrill YellowJackets ! Tommy Tune ! Wynton Marsalis ! Afro Rican Ensemble Allan Harris The Manhattan TransFerAndy Brown Astral Project Ahmad Jamal Allan Vache Andy Frasco Audrey Ryan Airto Moreira Almeda Trio Andy Hunter Avashai Cohen Alash Ensemble Alon Yavnai Andy Narell Avery Sharpe Albare Altan Ann Hampton Callaway Bad Plus Alex Bevan Alvin Frazier Ann Rabson Baldwin Wallace Musical Theater Department Alex Bugnon Amanda Martinez Anne Cochran Balkan Strings Banu Gibson Bob James Buzz Cronquist Christian Howes Barb Jungr Bob Reynolds BW Beatles Christian Scott Barbara Barrett Bobby Broom CaliFornia Guitar Trio Christine Lavin Barbara Knight Bobby Caldwell Carl Cafagna Chuchito Valdes Barbara Rosene Bobby Few Carmen Castaldi Chucho Valdes Baron Browne Bobby Floyd Carol Sudhalter Chuck Loeb Basia Bobby Sanabria Carol Welsman Chuck Redd Battlefield Band Circa 1939 Benny Golson Claudia Acuna Benny Green Claudia Hommel Benny Sharoni Clay Ross Beppe Gambetta Cleveland Hts. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Ann Braithwaite (781) 259-9600 [email protected]

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Ann Braithwaite (781) 259-9600 [email protected] Jazz at Princeton University inaugurates world’s newest jazz festival with headliner Dave Holland on Saturday, April 13 The first Princeton University Jazz Festival also features jazz superstars Donny McCaslin, Joel Frahm, Tia Fuller, Ingrid Jensen, Charenée Wade, Pedrito Martinez Jazz at Princeton University, helmed by acclaimed saxophonist/composer Rudresh Mahanthappa, presents the first Princeton University Jazz Festival on Saturday, April 13. The world’s newest jazz festival highlights a lineup featuring the bands of today’s top jazz stars as well as jazz greats playing with Princeton’s exceptional student groups. Free daytime performances, to be held outdoors at Alexander Beach in front of Princeton’s Richardson Auditorium, begin at noon. At 8 p.m., bassist Dave Holland will perform with Small Group I in a ticketed event at Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall, 68 Nassau Street. Tickets are $15, $5 students. For information please call 609-258-9220 or visit https://music.princeton.edu. Schedule of free performances: Noon-1 p.m.: Small Group X with Special Guest Joel Frahm, saxophone 1:20-2:20 p.m.: Small Group A with saxophonist Tia Fuller and trumpeter Ingrid Jensen 2:40-3:40 p.m.: Charenée Wade Quartet with Wade on vocals, pianist Oscar Perez, bassist Paul Beaudry, drummer Darrell Green 4-5 p.m.: Pedrito Martinez Group with Martinez on percussion and lead vocals; Isaac Delgado, Jr. on keyboards and vocals; Sebastian Natal on electric bass and vocals; Jhair Sala on percussion 5:20-6:30 p.m.: Donny McCaslin Quartet with McCaslin on saxophones, keyboardist Jason Lindner, bassist Jonathan Maron, drummer Zach Danziger “We are very excited to launch this new festival bringing together a wide array of today’s most creative and accomplished jazz artists performing with our remarkably talented students,” says Mahanthappa. -

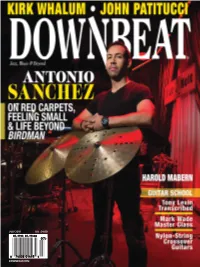

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

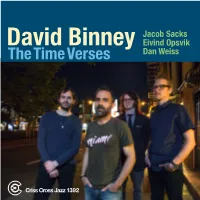

David Binney Eivind Opsvik the Time Verses Dan Weiss

Jacob Sacks David Binney Eivind Opsvik The Time Verses Dan Weiss Criss Cross Jazz 1392 The Time Verses Around the beginning of 2016, David Binney decided to build his next a unique sound,” Binney says. “There’s nothing that pigeonholes it into recording around the musicians who regularly play with him at the 55 Bar, a certain style or scene. Whatever sounds need to be made, will happen, the low-ceilinged ex-speakeasy on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village and the energy can go from unbelievably soft to completely nuts, from where, when not on the road, the alto saxophonist-composer has performed swinging to whatever. I feel lucky to have a regular gig with a regular band on Tuesdays since 2000, a year before he recorded the first of nine CDs that to develop music—especially improvised music. There’s a long history of he has led or co-led for Criss Cross. that in jazz, and it doesn’t happen much any more.” Even before launching his Tuesday night sinecure, Binney was To be specific, in 2001, Binney recruited Sacks, Weiss and Thomas using the 55 Bar as a place to workshop music and develop new bands, Morgan, each in their early twenties then, as his go-to band not long after sharing the cramped back corner “bandstand” with a who’s who of encountering them on a three-week European tour with trombonist Christoph contemporary improvisers, among them, pianists Uri Caine, Edward Simon, Schweizer. He first documented their simpatico on his 2004 Criss Cross Craig Taborn, David Virelles, John Escreet and Matt Mitchell; trumpeters debut, Bastion of Sanity [Criss 1261]. -

Dominican Republic Jazz Festival @ 20

NOVEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Inspiration Week Schedule ONLINE! - FALL 2020

Inspiration Week Schedule ONLINE! - FALL 2020 Inspiration Week (formerly Workshop Week) is November 22 –24! All Fall Semester Music Lesson students will attend an online workshop of their choice instead of their scheduled lesson during this week. Students must register in advance for a workshop of their choice by calling us at PMAC at 603-431-4278 or registering online at www.pmaconline.org. There are no costs to attend – this is part of our Fall Semester curriculum. Spaces are limited and available for PMAC Fall Music Lesson Students only! Inspired Kids for ages 12 & under Get moving, sing a new song, play a game, use your body as an instrument, learn new practicing skills! This year's Inspiration Week workshops have so much to offer! For students ages 10 and under, a parent or guardian must be available to attend the online workshop with their child. Music Jeopardy for ages 5-12 (Instructors: Ginna Macdonald & Kibbie Straw) Can you name that tune? How about naming a note on the staff? Can you tell the difference between an eighth note and sixteenth note? Test your music knowledge during a game of Musical Jeopardy! WORKSHOP DAY/TIME: Sunday, November 22 from 4:00PM – 4:45PM Music for Little Mozarts for ages 5-8 (Instructor: Tiffany Hanson) Sing, dance and make music! Connect with other music students at PMAC while learning rhythm and melodies. This introduction to music and the world of piano is sure to delight. WORKSHOP DAY/TIME: Monday, November 23 from 4PM – 4:30PM Body Music for ages 8-12 (Instructors: Jonny Peiffer & Mike Walsh) Learn a new instrument! Did you know you can use your body to play rhythms and create music? Join our percussion teaching artists and learn rhythmic components using your body as the instrument.