Dshang Universty Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minmap Region Du Littoral Synthese Des Donnees Sur La Base Des Informations Recueillies

MINMAP REGION DU LITTORAL SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de de Douala 94 89 179 421 671 3 2 Communité Urbaine d'édéa 5 89 000 000 14 3 Communité Urbaine de Nkongsamba 6 198 774 344 15 4 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 718 555 000 16 Département du Moungo 5 Services déconcentrés départementaux 5 145 000 000 18 6 Commune de BARE BAKEM 2 57 000 000 18 7 Commune de BONALEA 3 85 500 000 19 8 Commune de DIBOMBARI 3 105 500 000 19 9 Commune de LOUM 16 445 395 149 19 10 Commune de MANJO 8 132 000 000 21 11 Commune de MBANGA 3 108 000 000 22 12 Commune de MELONG 12 173 500 000 22 13 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 132 000 000 24 14 Commune d'EBONE 12 299 500 000 25 15 Commune de MOMBO 3 77 000 000 26 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 1 27 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 3 59 250 000 27 18 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 2 87 000 000 27 TOTAL Département 78 1 933 645 149 Département du Nkam 19 Services déconcentrés départementaux 12 232 596 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 16 258 623 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 14 221 000 000 31 22 Commune de YINGUI 4 53 500 000 33 23 Commune de NDOBIAN 17 345 418 000 33 TOTAL Département 63 1 111 137 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 90 960 000 36 25 Commune de Dibamba 3 72 000 000 37 26 Commune de Dizangue 5 88 500 000 37 27 Commune de MASSOCK 4 233 230 000 38 28 Commune de MOUANKO 15 582 770 000 38 29 Commune de NDOM 12 339 237 000 40 Nbre de N° Désignation -

MINMAP Région Du Littoral

MINMAP Région du Littoral SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine d'Edéa 6 1 747 550 008 3 2 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 10 534 821 000 4 TOTAL 16 2 282 371 008 Département du Wouri 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 246 700 000 5 4 Commune de Douala 1 9 370 778 000 5 5 Commune de Douala 2 9 752 778 000 6 6 Commune de Douala 3 12 273 778 000 8 7 Commune de Douala 4 10 278 778 000 9 8 Commune de Douala 5 10 204 605 268 10 9 Commune de Douala 6 10 243 778 000 11 TOTAL 66 2 371 195 268 Département du Moungo 10 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 159 560 000 12 11 Commune de Bare Bakem 9 234 893 804 13 12 Commune de Bonalea 11 274 397 840 14 13 Commune de Dibombari 11 267 278 000 15 14 Commune de Loum 12 228 397 903 16 15 Commune de Manjo 8 160 940 286 18 16 Commune de Mbanga 10 228 455 858 19 17 Commune de Melong 17 291 778 000 20 18 Commune de Njombe Penja 17 427 728 000 21 19 Commune d'Ebone 10 190 778 000 23 20 Commune de Mombo 9 163 878 000 24 21 Commune de Nkongsamba I 7 161 000 000 25 22 Commune de Nkongsamba II 6 172 768 640 25 23 Commune de Nkongsamba III 9 195 278 000 26 TOTAL 146 3 157 132 331 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 214 167 000 27 25 Commune de Dibamba 14 358 471 384 28 26 Commune de Dizangue 13 252 678 000 29 27 Commune de Massock 16 319 090 512 30 28 Commune de Mouanko 9 251 001 000 31 29 Commune de Ndom 17 340 778 000 31 30 Commune de Ngambe 9 235 -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

(Central Domain of the Cameroon North Equatorial Fold Belt): PT Data

JOURNAL OF THE CAMEROON ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 8 No. 2/3 (2009) Neoproterozoic metamorphic events in the kekem area (central domain of the Cameroon north equatorial fold belt): P-T data. TCHAPTCHET TCHATO D.c, NZENTI P. a, NJIOSSEU E. L.a, NGNOTUE, T.b, GANNO S.a a Laboratory of Structural Geology and Petrology of Orogenic Domains (LPGS), Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, P.O.Box 812, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon. b Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University of Dschang, Cameroon. c Laboratoire d’analyse des matériaux (MIPROMALO), B.P. 2396 Yaoundé. ABSTRACT The Kekem area (southwestern part of the central domain of the Cameroon North Equatorial Fold Belt) is composed of high-grade migmatitic gneisses in which two lithological units are distinguished: (i) a metasedimentary unit (garnet- sillimanite-biotite-gneisses and garnet-biotite-gneisses) interpreted as a continental series; and (ii) meta-igneous rocks comprising mafic pyroxene gneisses, amphibolites, and orthogneisses. These units recrystallised under HT-MP conditions (T=700-800°C, P ≥ 0.5-0.8GPa) and were deformed in relation to a major tangential tectonic event with the NNE-SSW kinematic direction. The lithological association and its tectono-metamorphic evolution show striking similarities with the Banyo and Maham III gneisses, suggesting that the extensional depositional environment envisaged for this formation can be extended farther west. P-T calculations in this contribution provide new data on the Pan-African structural and metamorphic evolution of the metapelites and metabasites in the basement of the Kekem area. The results show two distinct events: (1) crystallization during a Pan-African high temperature metamorphic event and, (2) subsequent deformation and high temperature mylonitization. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

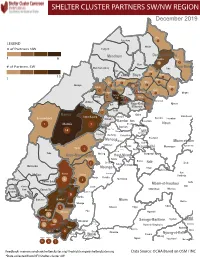

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Molecular Detection of Simulium Damnosum S.L, Vector Of

Journal of Veterinary Research Advances Research Article ISSN: 2582-774X Open access Molecular detection of Simulium damnosum S.l , Vector of Onchocerca volvulus in Sanaga Maritime (Littoral-Cameroon) Sevidzem Silas Lendzele 1 and Hiol Victor Dermy 2 1Laboratoire d’EcologieVectorielle (LEV-IRET), Libreville, Gabon 2Department of Parasitology and Parasitological Diseases, School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, University of Ngaoundere, Ngaoundere, Cameroon Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on: 18/02/2021 Accepted on: 06/03/2021 Published on: 18/03/2021 ABSTRACT Aim: The study was aimed to identify Simulium species of Mouanko using molecular tools. Method and Materials: Simulium biting humans were aspirated using a sucking tube for molecular identification. Fifty female Simulium flies were caught using the mentioned technique. Results: Molecular genotyping revealed that the anthropophilic Simulium black flies caught were of the Simulium damnosums.l. complex. Conclusion: The presence of Simulium damnosum s.l . indicates the risk of ongoing onchocercosis transmission in the study area. Keywords: Simulium , sucking tube, genotyping, Mouanko . Cite This Article as : Lendzele SS and Dermy HV (2021). Molecular detection of Simulium damnosum S.l , Vector of Onchocerca volvulus in Sanaga Maritime (Littoral-Cameroon). J. Vet. Res. Adv. 03(01): 25-27. Introduction Materials and Methods Human onchocercosis remains a threat to the Description of study area lives of individuals living in some rural Fly collection was conducted in the littoral region communities of Cameroon. The WHO/APOC precisely in Mouanko (Latitude 3° 38' 00’’North and survey report of 2011 revealed >60% prevalence Longitude 9° 47' 00’' East). Mouanko is a coastal of onchocercosis in some foci of the Center 1, town in the Sanaga-Maritime division in the Littoral 2 and West region (Tekle et al., 2016). -

Of the Kribi Region Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Environmental Assessment (REA) of the Kribi Region Public Disclosure Authorized National Hydrocarbon Corportion (SNH) 25 February 2008 Report 9S9906 Public Disclosure Authorized -a*a, saa ROYAL HASKONIIYQ HASKONING NEDERLAND B.V. ENVIRONMENT George Hintzenweg 85 P.O.Box 8520 Rollerdam 3009 AM The Netherlands t31 (0)lO 443 36 66 Telephone 00 31 10 4433 688 Fax [email protected] E-mail www.royalhaskoning.com Internet Arnhem 09122561 CoC Document title Regional Environmental Assessment (REA) of the Kribi Region Document short title REA Kribi Status Report Date 25 February 2008 Project name Project number 9S9906 Client National Hydrocarbon Corportion (SNH) Reference 9S9906/R00005/ACO/Rott Drafted by A.Corriol, R.Becqu6, H.Thorborg, R.Platenburg, A.Ngapoud, G.Koppert, A.Froment, Checked by F.Keukelaar Datelinitials check ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... Approved by R.Platenburg Datelinitials approval ... ................... ... .......... ..... .... REA Kribi 9S9906/R00005/ACO/Rott Report 25 February 2008 Abbrevlatlon Engllsh Engllsh French French used In report Abbrevlation Full text Abbreviation Full text N P NP National park PN Parc national OlTBC OlTBC Office lntercommunale de Tourisme de la Bande CGtiere PAP PAP Project Affected People PASEM PASEM Projet d'accompagnement socio economique (du barrage Memve'ele) PNUDIUNDP UNDP United Nations Development PNUD Progamme des Nations Program Unies pour le Developpement PPPA Plan for the preservation -

Mobile Phones, Social Capital and Solidarities in the Central Moungo Region (Cameroon)

”A human being without cell phones is akin to being lifeless”. Mobile phones, social capital and solidarities in the central Moungo region (Cameroon). Jérémy Pasini To cite this version: Jérémy Pasini. ”A human being without cell phones is akin to being lifeless”. Mobile phones, social capital and solidarities in the central Moungo region (Cameroon).. 2018. hal-01898381 HAL Id: hal-01898381 https://hal-univ-tlse2.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01898381 Preprint submitted on 18 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License "A HUMAN BEING WITHOUT A CELL PHONE IS AKIN TO BEING LIFELESS" (A) Mobile phones, social capital and solidarities in the central Moungo region (Cameroon)1 Jérémy PASINI2 (Ph.D. Student in geography, University of Toulouse, France) Summary. One of the most significant trends in Cameroon over the past two decades has been the rapid diffusion of the cellular telephony. The number of mobile phones' has risen from a few thousands in the early 2000s to more than seventeen million in 2014. How should we explain this unpreceded diffusion of cell phones? Why is it so crucial to be able to make phone calls and send short text messages, especially in coun- trysides and medium towns? This work starts from the hypothesis that Moungo's inhabitants can no longer build a resilient livelihood only from village resources (like the monetary salary arisen from the plantation) and are therefore always on the look-out for external unexplored occasions. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU LITTORAL EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° page Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 11 476 050 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 143 49 894 418 496 4 3 Communauté Urbaine de Nkongsamba 1 125 000 000 16 Département du Moungo 4 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 38 000 000 17 5 Commune de BARE BAKEM 9 312 790 000 17 6 Commune de BONALEA 24 412 000 000 17 7 Commune de DIBOMBARI 11 273 300 000 19 8 Commune de LOUM 8 186 600 000 20 9 Commune de MANJO 8 374 700 000 21 10 Commune de MBANGA 9 222 600 000 21 11 Commune de MELONG 13 293 140 184 22 12 Commune de NJOMBE PENJA 5 221 710 000 23 13 Commune d'EBONE 10 294 400 000 24 14 Commune de MOMBO 6 142 500 000 24 15 Commune de NKONGSAMBA I 11 245 833 000 25 16 Commune de NKONGSAMBA II 11 316 000 000 26 17 Commune de NKONGSAMBA III 6 278 550 000 27 TOTAL Département 133 3 612 123 184 Département du Nkam 18 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 16 000 000 28 19 Commune de NDOBIAN 12 309 710 000 28 20 Commune de NKONDJOCK 8 377 000 000 29 21 Commune de YABASSI 21 510 500 000 29 22 Commune de YINGUI 11 241 000 000 31 TOTAL Département 54 1 454 210 000 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 23 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 371 600 000 32 24 Commune de Dibamba 13 328 650 000 32 -

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Paix

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work - Fatherland MINISTRY OF MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2017 OF THE MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT SUBSECTOR FOREWORD The Ministry of Mines, Industry and Technological Development is pleased to present the statistical yearbook of the Mines, Industry and Technological Development sub-sector, MIDTSTAT, 2017edition. Its aim is to put at the disposal of actors of the sub-sector on the one hand, and of the general public, on the other hand, statistical data which illustrate the actions and development policies implemented in this ministerial department. The document presents a series of statistical information relating, on the one hand, to contextual data on Cameroon and, on the other hand, to the mines, industry and technological development components. I, therefore, invite all potential users of the information contained in this valuable document to make good use of it, and to generate actions likely to further improve the performance of our sub-sector. I would like to seize this opportunity to express my appreciation to all those who have, in one way or another, contributed towards elaborating this document, in particular the National Institute of Statistics for its support, the central and devolved services of MINMIDT, structures under its supervisory authority, as well as the administrations called upon to provide statistical information. We welcome suggestions and contributions likely to enrich and improve