Chapter-Ii Formation of Baroda State and Its Pre-Modern Basis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

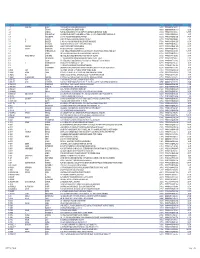

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study deals with “A critical study of Economic and Administrative policies of Nanasaheb peshwa. The following three chapters have been completed so far. The brief summary of the completed chapters are given below: Chapter – 1 Introductory chapter discusses the outline and aims of the study. It discusses while studying history, era of Shivaji and Peshwa are supposed to be the most important reign in the history of Maratha Power was planted in the reign of Shivaji and it was grown in the form of tree in the reign of Peshwa. The First four Peshwas shaped it in to imperialistic state. During the reign of shivaji, position of King was not given by hereditary. From the period of Shahu, position of Peshwa remained with only same dynasty. Bhat disguised in the Maratha power in the form of peshwa and it remained with that dynasty till to the end. Generally, the period from 1713 to 1818 is considered to be the period of peshwa. During this period most of the peshwas have shown their political diplomacy and administrative skill. They brought glory to the Maratha power by defeating the enemies from south and North. In the reign of Chattrapati Shahu Balaji Bajirao alias Nanasaheb Peshwa supposed to be the third Peshwa. In this era, he established vast empire which was never established before. During the span of 21 years Maratha had committed blunders. We find these blunders in the events o Raghuji Bhosale, Tulaji Angare and Panipat. He was known as skilled administrator. He gave financial stability by adopting the economic policies of agriculture, industry and land revenue system. -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Contemporary Stone Beadmaking in Khambhat, India

Contemporary Stone Beadmaking in Khambhat, India: Patterns of Craft Specialization and Organization of Production as Reflected in the Archaeological Record Author(s): Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Massimo Vidale, Kuldeep Kumar Bhan Reviewed work(s): Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 23, No. 1, Craft Production and Specialization (Jun., 1991), pp. 44-63 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/124728 . Accessed: 24/01/2012 13:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org Contemporarystone beadmaking in Khambhat, India: patterns of craft specialization and organization of production as reflected in the archaeologicalrecord Jonathan MarkKenoyer, Massimo Vidale and Kuldeep KumarBhan Introduction At present, the city of Khambhat in western India is one of the largest stone beadworking centers of the world, and it has been an important center for over two thousand years of documented history (Arkell 1936; Trivedi 1964) (Fig. 1). Using archaeological evidence, the stone bead industry in this region of India can be traced back even earlier to the cities and villages of the Harappan Phase of the Indus Tradition, dated to around 2500 BC (Hegde et al. -

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD AND SATI One unavoidable and important consequence of child-inan iages and the practice of polygamy w as a \ iin’s premature widowhood. During the period under study, there was not a single house that did not had a /vidow. Pause, one of the noblemen, had at one time 57 widows (Bodhya which meant widows whose heads A’ere tonsured) in the household A widow's life became a cruel curse, the moment her husband died. Till her husband was alive, she was espected and if she had sons, she was revered for hei' motherhood. Although the deatli of tiie husband, was not ler fault, she was considered inauspicious, repellent, a creature to be avoided at every nook and comer. Most of he time, she was a child-widow, and therefore, unable to understand the implications of her widowhood. Nana hadnavis niiirried 9 wives for a inyle heir, he had none. Wlien he died, two wives survived him. One died 14 Jays after Nana’s death. The other, Jiubai was very beautiful and only 9 years old. She died at the age of 66 r'ears in 1775 A.D. Peshwa Nanasaheb man'ied Radhabai, daugliter of Savkar Wakhare, 6 months before he died, Radhabai vas 9 years old and many criticised Nanasaheb for being mentally derailed when he man ied Radhabai. Whatever lie reasons for this marriage, he was sui-vived by 2 widows In 1800 A.D., Sardai' Parshurarnbhau Patwardlian, one of the Peshwa generals, had a daughter , whose Msband died within few months of her marriage. -

Creative Space,Vol

Creative Space,Vol. 5, No. 2, Jan. 2018, pp. 59–70 Creative Space Journal homepage: https://cs.chitkara.edu.in/ Alternative Modernity of the Princely states- Evaluating the Architecture of Sayajirao Gaekwad of Baroda Niyati Jigyasu Chitkara School of Planning and Architecture, Chitkara University, Punjab Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: August 17, 2017 The first half of the 20th century was a turning point in the history of India with provincial rulers Revised: October 09, 2017 making significant development that had positive contribution and lasting influence on India’s growth. Accepted: November 21, 2017 They served as architects, influencing not only the socio-cultural and economic growth but also the development of urban built form. Sayajirao Gaekwad III was the Maharaja of Baroda State from 1875 Published online: January 01, 2018 to 1939, and is notably remembered for his reforms. His pursuit for education led to establishment of Maharaja Sayajirao University and the Central Library that are unique examples of Architecture and structural systems. He brought many known architects from around the world to Baroda including Keywords: Major Charles Mant, Robert Chrisholm and Charles Frederick Stevens. The proposals of the urban Asian modernity, Modernist vision, Reforms, planner Patrick Geddes led to vital changes in the urban form of the core city area. Architecture New materials and technology introduced by these architects such as use of Belgium glass in the flooring of the central library for introducing natural light were revolutionary for that period. Sayajirao’s vision for water works, legal systems, market enterprises have all been translated into unique architectural heritage of the 20th century which signifies innovations that had a lasting influence on the city’s social, economic, administrative structure as well as built form of the city and its architecture. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

The Central Government in the Maratha Con Fad* Racy Bi

chapter IHRXE The Central Government In the Maratha Con fad* racy bi- chapter three Thg Central Govenwwit in the Mataiii| Cnnf<»^^racy The study of the central government of the Marathas In the elqhteenth century is a search for the dwindling* The power and authority of the central government under the Marathas both in theory and practice went on atrophying to such an extent that by the end of the eighteenth century very little of it remained. This was quite ironic, because the central govemiTient of the Marathas# to begin with, was strong and vigorous* The central government of ttw Marathas under Shivaji and his two sons was mainly represented by the Chhatrap>ati it was a strcxig and vigorous government* In the eighteenth « century, however, the power, though theoretically in the hands of the Chhatrapati, caiae to^be exercised by the Feshwa* In t^e ^^ c o n d half of the eighteenth centiiry/^the power ceune in the hands of the Karbharis of the Peshwa and in due course a Fadnis became the Peshwa of the Peshwa* The Peshwa and the Fj>dnis were like the^maller wheels within the big wheel represented by the Chhatrapati. While the . Peshwa was the servant of the Chhatrapati, the Karbharis were the servants of the Peshwa* The theoretical weakness of the Peshwa and the Karbharis did affect their position in practice ' h V 6 to a ccrtaln extent* ]i" - Maratha Kinadom and Chhatrapatl "■ --''iiMJwlKii'" ■ -j" 1 Shlvajl, prior to 1674, did lead the Marathas in western Maharashtra and had aiven them aovernnent, but the important requireinent of a state vig« sovereignty was gained in 1674 by the coronaticm ceremony* The significance of the coronation ceremony of Shivaji has been discussed by historians like Jadunath Sarkar* Sardesai and V .S.