Contemporary Stone Beadmaking in Khambhat, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Online Exhibition | Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture | 2020

Online Exhibition | Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture | 2020 Stepwells of Ahmedabad The settlement pattern of north central Gujarat evolved in response to its undulating terrain and was deeply influenced by the collection, preservation, and use of water (see Gallery 1). The travel routes that linked these settlements also followed paths charted by the seasonal movement of water across the region’s wrinkled, semi-arid landscape. The settlements formed a network tying major cities and port towns to small agricultural and artisanal villages that collectively constituted the region’s productive hinterland. The city of Ahmedabad, which emerged on the Sabarmati River, was an historic center of this network. The Sabarmati river originates in the Aravalli hills in the northeast, meanders through the gently undulating alluvial plains of north central Gujarat, and finally merges with the Arabian Sea at the Gulf of Khambhat in the south. About 50 miles north of the port city of Khambhat, Sultan Ahmad Shah, the ruler of the Gujarat Sultanate, built a citadel along the Sabarmati in 1411, formally establishing the city of Ahmedabad. The citadel was strategically situated on the river’s elevated eastern bank, anticipating the settlement’s future eastward expansion.1 Strategic elevations in the undulating terrain were identified as areas for dwelling.2 As a seasonal river, the Sabarmati swells during the monsoon and contracts in the summer, leaving dry large swathes. During its dry period, the riverbed became an expansive public space, bustling with temporary markets, circuses, and seasonal farming, as well as a variety of human activities such as washing, dyeing, and drying textiles.3 Soon after its establishment, Ahmedabad emerged as the region’s administrative capital and as an important node in the Indian Ocean trade network. -

District Census Handbook, 12 Kaira

CENSUS 1961 GUJARAT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 12 K·,AIRA DISTRICT R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census ,Operations. Gujarat PRICE Rs. 9.95 of. DISTRICT: KAIRA l () '<'0 ~ '<'15' '0 --;:::--- i(/~ ,,' 1<1 ,0 \ a: , I ...,<f "-,.\ :;) ) :I.:l CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Report I--B Report on Vital S~atistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables lI-A General Population Tables II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) I1-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) II-C Cultural and Migration Tables 111 Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIII-A Administra tion Report-Enumera tion I Not for Sale VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX A tlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CONTENTS PREFACE ALPHABETICAL LIST OF VILLAGES PART I (i) rntroductory Essay . 1-35 (1) Location and Physical Features, (2) Administrative Set-up, (3) Local Self Government, (4) Population, (5) Housing, (6) Agriculture, (7) Livestock, (8) Irrigation, (9) Co-operation, -

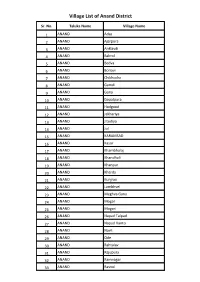

Village List of Anand District

Village List of Anand District Sr. No. Taluka Name Village Name 1 ANAND Adas 2 ANAND Ajarpura 3 ANAND Anklavdi 4 ANAND Bakrol 5 ANAND Bedva 6 ANAND Boriavi 7 ANAND Chikhodra 8 ANAND Gamdi 9 ANAND Gana 10 ANAND Gopalpura 11 ANAND Hadgood 12 ANAND Jakhariya 13 ANAND Jitodiya 14 ANAND Jol 15 ANAND KARAMSAD 16 ANAND Kasor 17 ANAND Khambholaj 18 ANAND Khandhali 19 ANAND Khanpur 20 ANAND Kherda 21 ANAND Kunjrao 22 ANAND Lambhvel 23 ANAND Meghva Gana 24 ANAND Mogar 25 ANAND Mogari 26 ANAND Napad Talpad 27 ANAND Napad Vanto 28 ANAND Navli 29 ANAND Ode 30 ANAND Rahtalav 31 ANAND Rajupura 32 ANAND Ramnagar 33 ANAND Rasnol 34 ANAND Samarkha 35 ANAND Sandesar 36 ANAND Sarsa 37 ANAND Sundan 38 ANAND Tarnol 39 ANAND Vadod 40 ANAND Vaghasi 41 ANAND Vaherakhadi 42 ANAND Valasan 43 ANAND Vans Khiliya 44 ANAND Vasad Village List of Petlad Taluka Sr. No. Taluka Name Village Name 1 PETLAD Agas 2 PETLAD Amod 3 PETLAD Ardi 4 PETLAD Ashi 5 PETLAD Bamroli 6 PETLAD Bandhani 7 PETLAD Bhalel 8 PETLAD Bhatiel 9 PETLAD Bhavanipura 10 PETLAD Bhurakui 11 PETLAD Boriya 12 PETLAD Changa 13 PETLAD Dantali 14 PETLAD Danteli 15 PETLAD Davalpura 16 PETLAD Demol 17 PETLAD Dhairyapura 18 PETLAD Dharmaj 19 PETLAD Fangani 20 PETLAD Ghunteli 21 PETLAD Isarama 22 PETLAD Jesarva 23 PETLAD Jogan 24 PETLAD Kaniya 25 PETLAD Khadana 26 PETLAD Lakkadpura 27 PETLAD Mahelav 28 PETLAD Manej 29 PETLAD Manpura 30 PETLAD Morad 31 PETLAD Nar 32 PETLAD Padgol 33 PETLAD Palaj 34 PETLAD Pandoli 35 PETLAD Petlad 36 PETLAD Porda 37 PETLAD Ramodadi 38 PETLAD Rangaipura 39 PETLAD Ravipura 40 PETLAD Ravli 41 PETLAD Rupiyapura 42 PETLAD Sanjaya 43 PETLAD Sansej 44 PETLAD Shahpur 45 PETLAD Shekhadi 46 PETLAD Sihol 47 PETLAD Silvai 48 PETLAD Simarada 49 PETLAD Sunav 50 PETLAD Sundara 51 PETLAD Sundarana 52 PETLAD Vadadala 53 PETLAD Vatav 54 PETLAD Virol(Simarada) 55 PETLAD Vishnoli 56 PETLAD Vishrampura Village List of Borsad Taluka Sr. -

Land Feature Extraction-Identification and Descrimincation Using Geospatial Techniques Case Study Along Sabarmati-Tapi Coastal Belt

Kalpa Publications in Civil Engineering Volume 1, 2017, Pages 248{258 ICRISET2017. International Conference on Re- search and Innovations in Science, Engineering &Technology. Selected papers in Civil Engineering Land Feature Extraction-Identification and Descrimincation Using Geospatial Techniques Case study along Sabarmati-Tapi Coastal belt Modi D S1, S N Bhandari2 and L. B. Zala1 1 Civil Engineering Dept.,BVM Engineering College,V V Nagar, Dist: Anand, Gujarat, India 2 Dept. of Earth and Env. Science (DEES), KSKV (Kutch) University,Kutch, Bhuj, Gujarat, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The Gulf of Cambay/Khambhat, (GoC), the study area is highly influenced by the tidal currents other than geological and structural set up of the region. In Gulf of Cambay, a large tidal range during high and low tides give rise to strong tidal currents and develops a mechanism of sediment transportation. Interestingly the inverted funnel shape of GoC has large contribution for the sediment deposition in this region. During high tide the tide currents move into the Gulf and encroaches the river mouth whereas during low tide, they move out. This regular phenomena since long period on geological time scale has modified the geomorphological features in this region. Along the major estuaries of Sabarmati, Mahi, Narmada and Tapi, the sediment budget is controlled by seasonal variation and also by tide and ebb phenomena. Using remote sensing images of different time scale and topographical map one can study the changes in geomorphological features. Satellite remote sensing technique has proven to be the paramount tool for studying surficial land features, especially for the inaccessible area or where time variable studies and regional scale studies are carried out. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : GUJARAT DISTRICT : Ahmadabad Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 VIJAYFARM CHELDA , PIN CODE: 382145, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: 0395646, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NA 10 - 50 NIC 2004 : 1020-Mining and agglomeration of lignite 2 SOMDAS HARGIVANDAS PRAJAPATI KOLAT VILLAGE DIST.AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1990 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 3 NABIBHAI PIRBHAI MOMIN KOLAT VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, 1992 10 - 50 E-MAIL : N.A. 4 NANDUBHAI PATEL HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 5 BODABHAI NO INTONO BHATHTHO HEBATPUR TA DASKROI DIST AHMEDABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 6 NARESHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , 2005 10 - 50 FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 7 SANDIPBHAI PRAJAPATI KTHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: 382430, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 8 JAYSHBHAI PRAJAPATI KATHAWADA VILLAGE DIST AHMEDABAD PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX 2005 10 - 50 NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

DAK 33 Spring 2019

Daak in Indian Languages Daak in Indian Languages Daak in Indian Languages Hindi Hindi Hindi Daak in Indian Languages Daak in Indian LanguagesHindi Hindi Daak in Indian Languages Daak in Indian Languages Sanskrit Malayalam Hindi Hindi Sanskrit MarathiMalayalam Punjabi Sanskrit Malayalam Marathi TeluguPunjabi Tamil Marathi Punjabi SanskritOdiya MalayalamKannada Telugu Tamil Sanskrit DaakMalayalam in IndianMarathi Languages Punjabi Telugu Tamil GujaratiSanskrit Malayalam Bangla Odiya Kannada ഡാക് Telugu Tamil Marathi Hindi Sanskrit Punjabi MarathiDaak Malayalam in Indian Languages Punjabi Tibetan ڈاک Odiya Kannada HindiDAKTelugu Tamil Telugu GujaratiMarathi Tamil DAKOdiya PunjabiBangla Kannada ڈاک The Newsletter of theUrdu American Institute of Indian StudiesOdiya Kannada Telugu Tamil Number 33 GujaratiSpring 2019 Bangla Gujarati Odiya Tibetan Bangla Kannada Gujarati Bangla Odiya Kannada TibetanTibetan Gujarati Bangla ڈاک Urdu Tibetan ڈاکGujarati Bangla ڈاک UrduUrdu Tibetan Tibetan Sanskrit Malayalam ڈاک Urdu Faculty Development Seminar Participants with Dr. Balasubramaniam in Mysore ڈاک Urdu as Students: The MarathiPower of Experiential Learning in India’s Growing Cities Punjabi ڈاکTeachers Urdu by Robin Kietlinski “Only when we take a comprehensive and ecosystem approach to our thinking, can we bring about meaningful and sustainable development for all.” —Dr. R. Balasubramaniam, Voices from the Grassroots Telugu continued on page 6 Tamil Odiya Kannada Gujarati Bangla Sanskrit Malayalam Tibetan Punjabiڈاک Marathi Urdu Telugu Tamil Odiya Kannada Gujarati Bangla Tibetan ڈاک Urdu AIIS 2019 Book Prizes Awarded to Dipti Khera and Bharat Venkat The Edward Cameron Dimock, Jr. Prize in the Indian Humanities was awarded to Dipti Khera for The Place of Many Moods: Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century. In her book, Professor Khera points out that by the early eighteenth century, Udaipur in Northwestern India was at the center of pioneering material and pictorial experiments in presenting the sensorial, embodied experience of space. -

Khambhat, District:- Anand, Gujarat-388

GUJARAT STATE ELECTRICITY CORPORATION LTD., Dhuvaran Thermal Power Station Taluka:- Khambhat, District:- Anand, Gujarat-388 610, India WEB TENDER NOTICE NO. 806 B (Downloadable) Separate item-wise sealed WEB Tender super-scribed with description of tender and its number for the following Supply / Works are invited in Two PART Bids irrespective of Estimated Cost. (Tenders- will NOT be issued in physical) Sr. Tender Estimated Tender Description of Tender. Section No. No. Cost in Rs. Fee 1 RFQ NO. Purchase of various sizes Gasket Purchase of 393 945.00 500.00 CCPP 27345 various sizes Gasket Sheets and Gland Packing MECH. for CCPP # 1 & 2 2 RFQ NO. Supply of LED type flameproof complete fixture 25652 0.00 500.00 CCPP 27438 for CCPP GBPS Dhuvaran. ELECT. 3 RFQ NO. SUUPLY OF REAGENT FOR TRANSASIA & 101080.00 500.00 HOSPITAL 27421 “SYSMAX” MAKE LABORATORY EQUIPMENT. 4 RFQ NO. Purchase of SUNISO -3GS Purchase of SUNISO - 28000.00 500.00 CCPP 27322 3GS OIL for AC plant compressors of CCPP- MECH. 1&2.OIL for AC plant 5 RFQ NO. Providing and Fixing M.S. angle Chajja to Door 500.00 CIVIL 27738 & Window of Single Storey F - Type Quarter's @ COLONY Dhuvaran, GBPS. 350000.00 Last submission date for Tender up to 15.00 hrs 31/012014 (By RPAD only) Due date of opening of Tender 31/012014 (If possible) at 15.30 hrs. (Tech Bid ) TERMS & CONDITIONS: (1) Tender fee & EMD have to be submitted along with all supporting/ qualifying documents, if not found offer will be out rightly rejected. -

All College List GIA-SF

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY AFFILIATED COLLEGES 1 Principal 2 Principal Anand Mercantile College of Science, AIMS College of Management & Technology Management & Computer Technology, AIMS Education Campus, Bhalej Road, Vadtal Road, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Bakrol – 388 001. (SFI) 3 Principal 4 Principal Akhilesh Sureshbhai Patel Arts College, Anand Arts College, At. & Po. Boriavi – 387 310 Sh. Ramkrishna S eva Mandal , Ta. & Dist. Anand (SFI) Nr. Grid, Anand - 388 001 (GIA/SFI) 5 Principal 6 Principal Anand College of Education, Anand Commerce College, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva M andal, Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (GIA/SFI) 7 Principal 8 Principal Anand Education College, Anand Homoeopathic Medical College & Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Research Institute, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Nr. Town Hall, Mandal, Nr. Sardar Baug, Anand - 388 001. (GIA) Anand - 388 001 (GIA) 9 Principal 10 Principal Anand Institute of P.G. Studies In Arts, Anand Institute of Business Studies, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Nr. Grid, Anand - 388 001 (SFI) Nr. Town Hall, Anand - 388 001. (SFI) 11 Principal 12 Principal Anand Institute of Social Work, Anand Law College, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Sh. Ramkrishna Seva Mandal, Nr. Town Hall, Nr. Town Hall , Anand - 388 001. (SFI) Anand - 388 001. (GIA/SFI) 13 Principal 14 Principal Ashok & Rita Patel Institute of Integrated Study Bhikhabhai Jivabhai Vanijya Mahavidyalaya &Research In Biotechnology And Allied Sciences (BJVM), (ARIBAS), Opp. Vitthal Udyognagar-GIDC, Vallabh Vidyanagar - 388 120. (GIA/SFI) Behind Phase-IV GIDC, New Vallabh Vidyanagar - 388 121. (SFI) 15 Principal 16 Principal B.N. -

Expansion of Onshore Oil & Gas Well Appraisal, Developmental Drilling and Production Through Surface Facilities

Pre-Feasibility Report for Expansion of Onshore Oil & Gas Well Appraisal, Developmental Drilling and Production through Surface Facilities Cambay Field Taluka Khambhat, District Anand Gujarat Oilex Ltd. 3rd Floor, Radha Arcade Block ‘C’, Nr. Swagat Rainforest 1, Kudasan Gandhinagar Koba Road Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 421 April, 2019 Pre-Feasibility Report, Onshore Oil & Gas Exploration, Development & Production Oilex Limited Cambay, Gujarat _________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents CHAPTERS Sr. No. Title Page No. 1.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Executive Summary 2/28 2.0 Introduction and Background 2.1 The proponent 4/28 2.2 Nature of the Project 5/28 2.3 Need of the project, Importance to Country/Region 5/28 2.4 Demand and Supply Gap 5/28 2.5 Import Vs Indigenous Production 5/28 2.6 Export Possibility 5/28 2.7 Domestic/Export Market 6/28 2.8 Employment Generation (Direct and Indirect) due to the Project 6/28 3.0 Project Description 3.0 Project Description 8/28 3.1 Type of Project including Interlinked or Interdependent Projects 8/28 3.2 Location of the Project 8/28 3.3 Alternative Sites 8/28 3.4 Size and Magnitude of Operation 8/28 3.5 Schematic of Process, Flow Diagram 11/28 3.6 Raw Materials Required 11/28 3.7 Resource Optimization/Recycling/Reuse 11/28 3.8 Water and Power Availability 11/28 3.9 Wastes – Solid, Liquid and Gaseous 11/28 4.0 Site Analysis 4.0 Site Analysis 14/28 4.1 Connectivity 14/28 4.2 Land forms, Landuse, Land ownership 14/28 4.3 Topography 14/28 4.4 Existing Land -

Indian Notices to Mariners

INDIAN NOTICES TO MARINERS EDITION NO. 12 DATED 16 JUN 2021 (CONTAINS NOTICES 131 TO 139) REACH US 24 x 7 [email protected] +91-135-2748373 [email protected] National Hydrographic Office Commander (H) 107-A, Rajpur Road Maritime Safety Information Services Dehradun – 248001 +91- 135 - 2746290-117 INDIA www.hydrobharat.gov.in CONTENTS Section No. Title I List of Charts Affected II Permanent Notices III Temporary and Preliminary Notices IV Marine Information V NAVAREA VIII Warnings inforce VI Corrections to Sailing Directions VII Corrections to List of Lights VIII Corrections to List of Radio Signals IX Corrections to Miscellaneous Nautical Publications X Reporting of Navigational Dangers ST TH (PUBLISHED ON NHO WEBSITE ON 1 & 16 OF EVERY MONTH) FEEDBACK: [email protected] INSIST ON INDIAN CHARTS AND PUBLICATIONS Original, Authentic and Up-to-Date © Govt. of India Copyright No permission is required to make copies of these Notices. However, such copies are not to be commercially sold. II MARINER’S OBLIGATION AND A CHART MAKER’S PLEA Observing changes at sea proactively and reporting them promptly to the concerned charting agency, is an obligation that all mariners owe to the entire maritime community towards SOLAS. Mariners are requested to notify the Chief Hydrographer to the Government of India at the above mentioned address/fax number/ E mail address immediately on discovering new or suspected dangers to navigation, changes/ defects pertaining to navigational aids, and shortcomings in Indian charts/ publications. The Hydrographic Note [Form IH – 102] is a convenient form to notify such changes. -

Paid Pending Applications As on Aug'19

PAID PENDING APPLICATIONS AS ON AUG'19 Circle: Anand Tentative Work Involved Sr Date Of Reg FQ Issue Date FQ Paid Date Month Of Scheme Sub Div Division Village Taluka District Name Load cat Remark No Work HT LT T/C Complition DD MM YYYY KM KM Cap DD MM YYYY DD MM YYYY V.V.NAGA 1 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Malek Murtujahusen ayubmiya 10 8 10 2018 C 0.19 16 to 25 22 7 2019 23 7 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA 2 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Patel Kanubhai Jashbhai 10 19 11 2018 B 0.025 0 22 7 2019 29 7 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA 3 SPA Anand City Bakrol Anand Anand Khureshi Asarafmiya Hasumiya 10 29 11 2018 C 0.17 10 to 16 22 7 2019 1 8 2019 Sep-19 R V.V.NAGA ANAND 4 SPA BAKROL Anand Anand PATEL JYOTIBEN NILESHBHAI 10 18 12 2018 D 0.08 10 KVA 22 7 2019 24 7 2019 Oct-19 R CITY 5 SPA Anand-S ANAND Khanpur Anand Anand Bhagvansinh Vakhatsinh Chakabhai Chauhan 10 18 5 2018 D 0.17 10 KVA 17 5 2019 11 6 2019 Sep-19 6 SPA Anand-S Anand Chikhodra Anand Anand Vasantbhai Ambalal Patel 15 2 7 2018 C 25 to 63 26 8 2019 27 8 2019 Sep-19 7 SPA Umreth-R Anand Chunel Mahudha Kheda Ravjibhai Bhikhabhai Prajapati 10 3 7 2018 D 0.63 10 KVA 25 6 2019 27 6 2019 Nov-19 Way problem 8 SPA Umreth-R Anand Parvata Umreth Anand Kesharbhai Chunabhai Rathod 7.5 9 7 2018 C 0.05 16 to 25 25 6 2019 11 7 2019 Sep-19 Standing paddy 9 SPA Umreth-R Anand Chunel Mahudha Kheda Pravinbhai Bhikhabhai Patel 7.5 19 7 2018 C 0.3 10 to 16 25 6 2019 2 7 2019 Nov-19 crop.photographs taken.