Writing the Transnational History of Science and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landsat Collection 2

Landsat Collection 2 Landsat Collection 2 marks the second major reprocessing of the U.S. Geological Top of atmosphere Surface reflectance Surface temperature Survey (USGS) Landsat archive. In 2016, the USGS formally reorganized the Landsat archive into a tiered collection inventory structure in recognition of the need for consis- tent Landsat 1–8 sensor data and in anticipa- tion of future periodic reprocessing of the archive to reflect new sensor calibration and geolocation knowledge. Landsat Collections ensure that all Landsat Level-1 data are con- sistently calibrated and processed and retain traceability of data quality provenance. Bremerton Landsat Collection 2 introduces improvements that harness recent advance- ments in data processing, algorithm develop- ment, data access, and distribution capabili- N ties. Collection 2 includes Landsat Level-1 data for all sensors (including Landsat 9, Figure 1. Landsat 5 Collection 2 Level-1 top of atmosphere (TOA; left). Corresponding when launched) since 1972 and global Collection 2 Level-2 surface reflectance (SR; center) and surface temperature (ST [K]; right) Level-2 surface reflectance and surface images. temperature scene-based products for data acquired since 1982 starting with the Landsat Digital Elevation Models Thematic Mapper (TM) sensor era (fig. 1). The primary improvements of Collection 2 data include Collection 2 uses the 3-arc-second (90-meter) digital eleva- • rebaselining the Landsat 8 Operational Landsat Imager tion modeling sources listed and illustrated below. (OLI) Ground -

Information Summaries

TIROS 8 12/21/63 Delta-22 TIROS-H (A-53) 17B S National Aeronautics and TIROS 9 1/22/65 Delta-28 TIROS-I (A-54) 17A S Space Administration TIROS Operational 2TIROS 10 7/1/65 Delta-32 OT-1 17B S John F. Kennedy Space Center 2ESSA 1 2/3/66 Delta-36 OT-3 (TOS) 17A S Information Summaries 2 2 ESSA 2 2/28/66 Delta-37 OT-2 (TOS) 17B S 2ESSA 3 10/2/66 2Delta-41 TOS-A 1SLC-2E S PMS 031 (KSC) OSO (Orbiting Solar Observatories) Lunar and Planetary 2ESSA 4 1/26/67 2Delta-45 TOS-B 1SLC-2E S June 1999 OSO 1 3/7/62 Delta-8 OSO-A (S-16) 17A S 2ESSA 5 4/20/67 2Delta-48 TOS-C 1SLC-2E S OSO 2 2/3/65 Delta-29 OSO-B2 (S-17) 17B S Mission Launch Launch Payload Launch 2ESSA 6 11/10/67 2Delta-54 TOS-D 1SLC-2E S OSO 8/25/65 Delta-33 OSO-C 17B U Name Date Vehicle Code Pad Results 2ESSA 7 8/16/68 2Delta-58 TOS-E 1SLC-2E S OSO 3 3/8/67 Delta-46 OSO-E1 17A S 2ESSA 8 12/15/68 2Delta-62 TOS-F 1SLC-2E S OSO 4 10/18/67 Delta-53 OSO-D 17B S PIONEER (Lunar) 2ESSA 9 2/26/69 2Delta-67 TOS-G 17B S OSO 5 1/22/69 Delta-64 OSO-F 17B S Pioneer 1 10/11/58 Thor-Able-1 –– 17A U Major NASA 2 1 OSO 6/PAC 8/9/69 Delta-72 OSO-G/PAC 17A S Pioneer 2 11/8/58 Thor-Able-2 –– 17A U IMPROVED TIROS OPERATIONAL 2 1 OSO 7/TETR 3 9/29/71 Delta-85 OSO-H/TETR-D 17A S Pioneer 3 12/6/58 Juno II AM-11 –– 5 U 3ITOS 1/OSCAR 5 1/23/70 2Delta-76 1TIROS-M/OSCAR 1SLC-2W S 2 OSO 8 6/21/75 Delta-112 OSO-1 17B S Pioneer 4 3/3/59 Juno II AM-14 –– 5 S 3NOAA 1 12/11/70 2Delta-81 ITOS-A 1SLC-2W S Launches Pioneer 11/26/59 Atlas-Able-1 –– 14 U 3ITOS 10/21/71 2Delta-86 ITOS-B 1SLC-2E U OGO (Orbiting Geophysical -

The Space-Based Global Observing System in 2010 (GOS-2010)

WMO Space Programme SP-7 The Space-based Global Observing For more information, please contact: System in 2010 (GOS-2010) World Meteorological Organization 7 bis, avenue de la Paix – P.O. Box 2300 – CH 1211 Geneva 2 – Switzerland www.wmo.int WMO Space Programme Office Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 85 19 – Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 84 74 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wmo.int/pages/prog/sat/ WMO-TD No. 1513 WMO Space Programme SP-7 The Space-based Global Observing System in 2010 (GOS-2010) WMO/TD-No. 1513 2010 © World Meteorological Organization, 2010 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate these publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0)22 730 84 03 P.O. Box No. 2300 Fax: +41 (0)22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] FOREWORD The launching of the world's first artificial satellite on 4 October 1957 ushered a new era of unprecedented scientific and technological achievements. And it was indeed a fortunate coincidence that the ninth session of the WMO Executive Committee – known today as the WMO Executive Council (EC) – was in progress precisely at this moment, for the EC members were very quick to realize that satellite technology held the promise to expand the volume of meteorological data and to fill the notable gaps where land-based observations were not readily available. -

NASA Process for Limiting Orbital Debris

NASA-HANDBOOK NASA HANDBOOK 8719.14 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Approved: 2008-07-30 Washington, DC 20546 Expiration Date: 2013-07-30 HANDBOOK FOR LIMITING ORBITAL DEBRIS Measurement System Identification: Metric APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE – DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 2 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 DOCUMENT HISTORY LOG Status Document Approval Date Description Revision Baseline 2008-07-30 Initial Release Page 3 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 4 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 This page intentionally left blank. Page 6 of 174 NASA-Handbook 8719.14 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SCOPE...........................................................................................................................13 1.1 Purpose................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Applicability ....................................................................................................................... 13 2 APPLICABLE AND REFERENCE DOCUMENTS................................................14 3 ACRONYMS AND DEFINITIONS ...........................................................................15 3.1 Acronyms............................................................................................................................ 15 3.2 Definitions ......................................................................................................................... -

Automated Cloud and Cloud Shadow Identification in Landsat MSS Imagery for Temperate Ecosystems

Automated cloud and cloud shadow identification in Landsat MSS imagery for temperate ecosystems Braaten, J. D., Cohen, W. B., & Yang, Z. (2015). Automated cloud and cloud shadow identification in Landsat MSS imagery for temperate ecosystems. Remote Sensing of Environment, 169, 128-138. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2015.08.006 10.1016/j.rse.2015.08.006 Elsevier Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Remote Sensing of Environment 169 (2015) 128–138 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Remote Sensing of Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rse Automated cloud and cloud shadow identification in Landsat MSS imagery for temperate ecosystems Justin D. Braaten a,⁎,WarrenB.Cohenb, Zhiqiang Yang a a Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, 321 Richardson Hall, Corvallis, OR 97331, United States b Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Corvallis, OR 97331, United States article info abstract Article history: Automated cloud and cloud shadow identification algorithms designed for Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) and Received 14 October 2014 Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) satellite images have greatly expanded the use of these Earth observation data Received in revised form 27 July 2015 by providing a means of including only clear-view pixels in image analysis and efficient cloud-free compositing. Accepted 6 August 2015 In an effort to extend these capabilities to Landsat Multispectal Scanner (MSS) imagery, we introduce MSS clear- Available online 21 August 2015 view-mask (MSScvm), an automated cloud and shadow identification algorithm for MSS imagery. The algorithm fi Keywords: is speci c to the unique spectral characteristics of MSS data, relying on a simple, rule-based approach. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District. -

A Global Land-Observing Program, Fact Sheet 023-03 (March 2003) 05/31/2006 12:58 PM

Landsat: A Global Land-Observing Program, Fact Sheet 023-03 (March 2003) 05/31/2006 12:58 PM Landsat: A Global Land-Observing Program Fact Sheet 023-03 (March 2003) || A Brief History of the Landsat Program || Characteristics of the Landsat System || || Applications of Landsat Data || Landsat Data Continuity Mission || Information || The Landsat Program is a joint effort of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to gather Earth resource data using a series of satellites. NASA was responsible for developing and launching the spacecrafts. The USGS is responsible for flight operations, maintenance, and management of all ground data reception, processing, archiving, product generation, and distribution. A primary objective of the Landsat Program is to ensure a collection of consistently calibrated Earth imagery. Landsat's mission is to establish and execute a data acquisition strategy that ensures the repetitive acquisition of observations over the Earth's land mass, coastal boundaries, and coral reefs and to ensure that the data acquired are of maximum utility in supporting the scientific objective of monitoring changes in the Earth's land surface. || Top || Main Table of Contents || A Brief History of the Landsat Program In the mid-1960s, stimulated by success in planetary exploration using unmanned remote sensing satellites, the Department of the Interior, NASA, the Department of Agriculture, and others embarked on an ambitious initiative to develop and launch the first civilian Earth-observing satellite to meet the needs of resource managers and earth scientists. The USGS assumed responsibility for archiving the data acquired by the new program and for distributing the anticipated data product. -

Press Kit Pr°I§£L LANDSAT D RELEASE NO: 82-100

News National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D.C. 20546 AC 202 755-8370 For Release IMMEDIATE Press Kit Pr°i§£L LANDSAT D RELEASE NO: 82-100 (NASA-News-Belease-82-100)- 1ANDSAT D TO ' • N82-26741 TEST THEHATIC HAPPEE, INAUGURATE -. CPEKATIONAL SYSTEM (National Aeronautics and Space f , Administration) 43 p...Avail;r ;> NASA .. ' ^ unclfa;s\. VW Scientific_and. Technical Inf CSCX_22A -00/43 _ 24227v V Contents GENERAL RELEASE 1 THE LANDSAT STORY 5 DESCRI PTION OF OPERATIONAL SYSTEM 16 PLANNING TO MEET USER NEEDS 17 MISSION DESCRIPTION. 18 LAUNCH VEHICLE DESCRIPTION 19 LANDSAT D FLIGHT SEQUENCE OF EVENTS 22 SPACECRAFT ACTI VATION . 24 SPACECRAFT DESCRI PTION 27 MULTI SPECTRAL SCANNER 32 THEMATIC MAPPER ............ 35 LANDSAT D GROUND PROCESSING SYSTEM 38 NASA LANDSAT D PROGRAM MANAGEMENT 40 CONTRACTORS 42 IWNSANews National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D.C. 20546 AC 202 755-8370 For Release. Charles Redmond IMMEDIATE Headquarters, Washington, D.C. (Phone: 202/755-3680) James C. Elliott Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md. (Phone: 301/344-8955) Hugh Harris Kennedy Space Center, Fla. (Phone: 305/867-2468) RELEASE NO: 82-100 LANDSAT D TO TEST THEMATIC MAPPER, INAUGURATE OPERATIONAL SYSTEM NASA will launch the Landsat D spacecraft, a new generation Earth resources satellite, from the Western Space and Missile Center, Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., no earlier than 1:59 p.m. EOT July 9, 1982, aboard a new, up-rated Delta 3920 expend- able launch vehicle. Landsat D will incorporate two highly sophisticated sensors: the flight proven multispectral scanner (MSS), one of the sensors on the Landsat 1, 2 and 3 spacecraft; and a new instrument ex- pected to advance considerably the remote sensing capabilities of Earth resources satellites. -

<> CRONOLOGIA DE LOS SATÉLITES ARTIFICIALES DE LA

1 SATELITES ARTIFICIALES. Capítulo 5º Subcap. 10 <> CRONOLOGIA DE LOS SATÉLITES ARTIFICIALES DE LA TIERRA. Esta es una relación cronológica de todos los lanzamientos de satélites artificiales de nuestro planeta, con independencia de su éxito o fracaso, tanto en el disparo como en órbita. Significa pues que muchos de ellos no han alcanzado el espacio y fueron destruidos. Se señala en primer lugar (a la izquierda) su nombre, seguido de la fecha del lanzamiento, el país al que pertenece el satélite (que puede ser otro distinto al que lo lanza) y el tipo de satélite; este último aspecto podría no corresponderse en exactitud dado que algunos son de finalidad múltiple. En los lanzamientos múltiples, cada satélite figura separado (salvo en los casos de fracaso, en que no llegan a separarse) pero naturalmente en la misma fecha y juntos. NO ESTÁN incluidos los llevados en vuelos tripulados, si bien se citan en el programa de satélites correspondiente y en el capítulo de “Cronología general de lanzamientos”. .SATÉLITE Fecha País Tipo SPUTNIK F1 15.05.1957 URSS Experimental o tecnológico SPUTNIK F2 21.08.1957 URSS Experimental o tecnológico SPUTNIK 01 04.10.1957 URSS Experimental o tecnológico SPUTNIK 02 03.11.1957 URSS Científico VANGUARD-1A 06.12.1957 USA Experimental o tecnológico EXPLORER 01 31.01.1958 USA Científico VANGUARD-1B 05.02.1958 USA Experimental o tecnológico EXPLORER 02 05.03.1958 USA Científico VANGUARD-1 17.03.1958 USA Experimental o tecnológico EXPLORER 03 26.03.1958 USA Científico SPUTNIK D1 27.04.1958 URSS Geodésico VANGUARD-2A -

Landsat—Earth Observation Satellites

Landsat—Earth Observation Satellites Since 1972, Landsat satellites have continuously acquired space- In the mid-1960s, stimulated by U.S. successes in planetary based images of the Earth’s land surface, providing data that exploration using unmanned remote sensing satellites, the serve as valuable resources for land use/land change research. Department of the Interior, NASA, and the Department of The data are useful to a number of applications including Agriculture embarked on an ambitious effort to develop and forestry, agriculture, geology, regional planning, and education. launch the first civilian Earth observation satellite. Their goal was achieved on July 23, 1972, with the launch of the Earth Resources Landsat is a joint effort of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Technology Satellite (ERTS-1), which was later renamed and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Landsat 1. The launches of Landsat 2, Landsat 3, and Landsat 4 NASA develops remote sensing instruments and the spacecraft, followed in 1975, 1978, and 1982, respectively. When Landsat 5 then launches and validates the performance of the instruments launched in 1984, no one could have predicted that the satellite and satellites. The USGS then assumes ownership and operation would continue to deliver high quality, global data of Earth’s land of the satellites, in addition to managing all ground reception, surfaces for 28 years and 10 months, officially setting a new data archiving, product generation, and data distribution. The Guinness World Record for “longest-operating Earth observation result of this program is an unprecedented continuing record of satellite.” Landsat 6 failed to achieve orbit in 1993; however, natural and human-induced changes on the global landscape. -

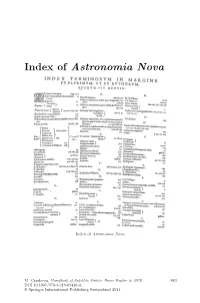

Index of Astronomia Nova

Index of Astronomia Nova Index of Astronomia Nova. M. Capderou, Handbook of Satellite Orbits: From Kepler to GPS, 883 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-03416-4, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Bibliography Books are classified in sections according to the main themes covered in this work, and arranged chronologically within each section. General Mechanics and Geodesy 1. H. Goldstein. Classical Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, Mass., 1956 2. L. Landau & E. Lifchitz. Mechanics (Course of Theoretical Physics),Vol.1, Mir, Moscow, 1966, Butterworth–Heinemann 3rd edn., 1976 3. W.M. Kaula. Theory of Satellite Geodesy, Blaisdell Publ., Waltham, Mass., 1966 4. J.-J. Levallois. G´eod´esie g´en´erale, Vols. 1, 2, 3, Eyrolles, Paris, 1969, 1970 5. J.-J. Levallois & J. Kovalevsky. G´eod´esie g´en´erale,Vol.4:G´eod´esie spatiale, Eyrolles, Paris, 1970 6. G. Bomford. Geodesy, 4th edn., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1980 7. J.-C. Husson, A. Cazenave, J.-F. Minster (Eds.). Internal Geophysics and Space, CNES/Cepadues-Editions, Toulouse, 1985 8. V.I. Arnold. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (60), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1989 9. W. Torge. Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991 10. G. Seeber. Satellite Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993 11. E.W. Grafarend, F.W. Krumm, V.S. Schwarze (Eds.). Geodesy: The Challenge of the 3rd Millennium, Springer, Berlin, 2003 12. H. Stephani. Relativity: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity,Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004 13. G. Schubert (Ed.). Treatise on Geodephysics,Vol.3:Geodesy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2007 14. D.D. McCarthy, P.K. -

TBE Technicalreport CS91-TR-JSC-017 U

Hem |4 W TBE TechnicalReport CS91-TR-JSC-017 u w -Z2- THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE NIMBUS 6 ROCKET BODY i w i David J. Nauer SeniorSystems Analyst Nicholas L. Johnson Advisory Scientist November 1991 Prepared for: t_ NASA Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 m Contract NAS9-18209 DRD SE-1432T u Prepared by: Teledyne Brown Engineering ColoradoSprings,Colorado 80910 m I i l Id l II a_wm n IE m m I NI g_ M [] l m IB g II M il m Im mR z M i m The Fragmentation of the Nimbus 6 Rocket Body Abstract: On 1 May 1991 the Nimbus 6 second stage Delta Rocket Body experienced a major breakup at an altitude of approximately 1,100km. There were numerous piecesleftin long- livedorbits,adding to the long-termhazard in this orbitalregime already°presentfrom previousDelta Rocket Body explosions. The assessedcause of the event is an accidentalexplosionof the Delta second stageby documented processesexperiencedby other similar Delta second stages. Background _-£ W Nimbus 6 and the Nimbus 6 Rocket Body (SatelliteNumber 7946, InternationalDesignator i975-052B) were launched from the V_denberg WeStern Test Range on 12 June 1975. The w Delta 2910 launch vehicleloftedthe 830 kg Nimbus 6 Payload into a sun-synchronous,99.6 degree inclination,1,100 km high orbit,leaving one launch fragment and the Delta Second N Stage Rocket Body. This was the 23_ Delta launch of a Second Stage Rocket Body in the Delta 100 or laterseriesofboostersand the 111_ Delta launch overall. k@ On 1 May 1991 the Nimbus 6 Delta second stage broke up into a large,high altitudedebris cloud as reportedby a NAVSPASUR data analysismessage (Appendix 1).