Balsam Woolly Adelgid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balsam Woolly Adelgid

A New Utah Forest Insect This fact sheet Pest: Balsam Woolly Adelgid introduces an invasive forest pest, the balsam By: Darren McAvoy, Extension Forestry Assistant Professor, woolly adelgid, and Diane Alston, Professor & Extension Entomologist, discusses its impacts on Ryan Davis, Arthropod Diagnostician, Utah forests, life cycle Megan Dettenmaier, Extension Forestry Educator traits, identifying characteristics, control Introduction methods, and steps that In 2017, the USDA Forest Service’s Forest Health Protection (FHP) group in Utah partners are taking Ogden, Utah detected and confirmed the presence of a new invasive forest to combat this pest. pest in Utah called the balsam woolly adelgid (BWA). First noticed in the mountains above Farmington Canyon and near Powder Mountain Resort, it has Dieback and decline of subalpine fir due to attack by balsam woolly adelgid. Photo credit: Darren McAvoy. 2017, forest health professionals visited Farmington Canyon on the ground and found branch node swelling (a node is where branch structures come together) and old deposits of woolly material on mature subalpine fir trees. Suspected to have originated in the Caucasus Mountains between Europe and Asia, BWA was first detected in North America in Maine, in 1908, and in California about 20 years later. It was detected in Idaho near Coeur d’Alene in 1983 and has since spread across northern Idaho. It is believed that separate invasions of subspecies or races of BWA may differentially impact tree host species. Dieback of subalpine fir, pacific silver (Abies amabilis) and grand fir (A. grandis) in Idaho is widespread. In the western Payette National Forest, north of Boise, an estimated 70% of subalpine fir trees are dead and falling down. -

2004A IE Reports

Contents Introduction…………………………………….…………………………………1 Using GIS to predict plant distributions: a new approach (Amy Lorang)……………………………………………………………………...3 Impacts of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid on Canadian and Carolina Hemlock Forests (Josh Brown)………………………………………………..……………………19 Effects of Adelgid-Induced Decline in Hemlock Forests on Terrestrial Salamander Populations of the Southern Appalachians: A Preliminary Study (Shelley Rogers)………………………………………………………………….37 Riparian zone structure and function in Southern Appalachian forested headwater catchments (Katie Brown)…………………………………………………………………….60 Successional Dynamics of Dulany Bog (Michael Nichols)………………………………………………………………...77 Mowing and its Effect on the Wildflowers of Horse Cove Road on the Highlands Plateau ((Megan Mailloux)……………………………………………………………….97 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………..114 1 Introduction In the Fall of 2004, twelve undergraduate students from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had the opportunity to complete ecological coursework through the Carolina Environmental Program’s Highlands field site. This program allows students to learn about the rich diversity of plants and animals in the southern Appalachians. The field site is located on the Highlands Plateau, North Carolina, near the junction of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The plateau is surrounded by diverse natural areas which create an ideal setting to study different aspects of land use change and threats to biodiversity. The Highlands Plateau is a temperate rainforest of great biodiversity, a patchwork of rich forests, granite outcrops, and wet bogs. Many rare or interesting species can be found in the area, with some being endemic to a specific stream or mountaintop. Some of these are remnants of northern species that migrated south during the last ice age; others evolved to suit a particular habitat, with a slightly different species in each stream. -

Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID TECHNICALCONTRIBUTORS: RICHARD REARDON FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM, USDA FOREST SERVICE, MORGANTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA BRAD ONKEN FOREST HEALTH PROTECTION, USDA FOREST SERVICE, MORGANTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA AUTHORS: CAROLE CHEAH THE CONNECTICUT AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION MIKE MONTGOMERY NORTHEASTERN RESEARCH STATION SCOTT SALEM VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY BRUCE PARKER, MARGARET SKINNER, SCOTT COSTA UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT FHTET-2004-04 U.S. Department Forest of Agriculture Service FHTET he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in T1995 by the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ On the cover Clockwise from top left: adult coccinellids Sasajiscymnus tsugae, Symnus ningshanensis, and Scymnus sinuanodulus, adult derodontid Laricobius nigrinus, hemlock woolly adelgid infected with Verticillium lecanii. For copies of this publication, please contact: Brad Onken Richard Reardon Forest Health Protection Forest Health Technology Enterprise Morgantown, West Virginia Team Morgantown, West Virginia 304-285-1546 304-285-1566 [email protected] [email protected] All images in the publication are available online at http://www.forestryimages.org and http://www.invasive.org Reference numbers for the digital files appear in the figure captions in this publication. The entire publication is available online at http://www.bugwood.org and http://www.fs.fed.us/na/morgantown/fhp/hwa. The U.S. -

2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Great Smoky Mountains National Park - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment Great Smoky Mountains National Park 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment SITE INFORMATION Country: United States of America (USA) Inscribed in: 1983 Criteria: (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) Stretching over more than 200,000 ha, this exceptionally beautiful park is home to more than 3,500 plant species, including almost as many trees (130 natural species) as in all of Europe. Many endangered animal species are also found there, including what is probably the greatest variety of salamanders in the world. Since the park is relatively untouched, it gives an idea of temperate flora before the influence of humankind. © UNESCO SUMMARY 2020 Conservation Outlook Finalised on 04 Dec 2020 GOOD WITH SOME CONCERNS The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is inscribed on the World Heritage List for its scenery and biodiversity. The scenic vistas offered by the park are largely maintained, with incremental improvement in pollution legislation and practice in recent decades making marked improvements in air quality, which has reduced haze despite ongoing visitor management issues and the threats affecting forests which are such a feature of the scenery, most notably seen in the remnant dead pines protruding from forest canopies. The biological values are in variable condition across the wide range of ecosystems contained within the site. Mesic systems such as Cove forest, which covers the largest area of any ecological system in the site, are generally in good condition, whilst the more xeric systems such as low-altitude pine and dry oak forests are showing concerning departures from their natural state. -

Chapter 16. Evaluating Host Range of Laricobius Nigrinus for Introduction Into the Eastern United States for Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

ASSESSING HOST RANGES OF PARASITOIDS AND PREDATORS _________________________________ CHAPTER 16. EVALUATING HOST RANGE OF LARICOBIUS NIGRINUS FOR INTRODUCTION INTO THE EASTERN UNITED STATES FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID G. Zilahi-Balogh Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Harrow, Ontario, Canada [email protected] HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID IN NORTH AMERICA The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae Annand (Homoptera: Adelgidae), is a serious threat to hemlock landscape and forest stands in the eastern United States (McClure, 1996). Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis [L.] Carr.) and Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana Engelm.) are very susceptible to HWA attack, and infested trees have died in as little as four years (McClure, 1991). DISTRIBUTION OF HWA HWA is believed to have originated in Asia (McClure, 1987), and was first observed in North America in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1920s, where Annand (1924) described it from specimens collected on western hemlock, Tsuga heterophylla (Raf.) Sargent, in Oregon. An earlier description in 1922 identified the species as Chermes funitectus Dreyfus, also from west- ern hemlock in Vancouver, British Columbia (Annand, 1928). Annand (1928) reported that the two species were the same. HWA is exotic to eastern North America (McClure, 1987). First collected in the eastern United States in Virginia in 1951 in an ornamental setting (Stoetzel, 2002), it has spread to forests where it currently occurs in parts of 16 states along the eastern seaboard from North Carolina to New England (USDA FS, 2004). The main front of the HWA infestation is ad- vancing at approximately 25 km per year (McClure, 2001). There are nine recognized species of hemlock (Farjon, 1990). -

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Facsheet Dec 2018

Dr. Carole Cheah Valley Laboratory The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 153 Cook Hill Road, P. O. Box 248 Windsor, CT 06095 Phone: (860) 683-4980 Fax: (860) 683-4987 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) and Other Factors Impacting Eastern Hemlock Introduction and Overview Adelgids are small conifer-feeding insects, related to aphids, belonging to the Suborder Homoptera (1). Hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae Annand, (HWA), feeds specifically on hemlock species and was first described from samples originally from Oregon by P. N. Annand in California in 1924 (2). In North America, native Eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carriere and Carolina hemlock, Tsuga caroliniana Engelmann are very susceptible to HWA attack (3). Eastern hemlock is the seventh most common tree species in Connecticut and the second most abundant conifer after eastern white pine (4). In the eastern United States, this non- native insect pest was initially reported at a private estate in Richmond, Virginia in the early 1950s (5). The hemlock woolly adelgid in eastern US originated from southern Honshu island, Japan (6) and infestations have since spread widely to attack eastern hemlock and Carolina hemlock in 20 eastern states, from the southern Appalachians in the Carolinas and Georgia, through the Mid-Atlantic States, westwards to Ohio and Michigan and northwards to northern New England (7). Most recently, HWA was found in southern Nova Scotia in Canada in 2017 (8). In Connecticut, HWA was first reported to the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven in 1985 and by 1997, was found throughout the state, in all 169 Connecticut towns (7). -

Balsam Woolly Adelgid Management

Forest Health Protection and March 2010 State Forestry Partners 7.6 WEB July 2010 Management Guide for R. Ladd Livingston Balsam Woolly Adelgid Lee Pederson, US Forest Service Adelges piceae (Ratzeburg) Topics Subalpine fir is most susceptible. Grand fir is most resistant to damage. Overview 1 All true firs may be hosts. Life History 2 Natural Control 2 This European invader was first found in northern Idaho in 1983. It has expanded south to the Silvicultural 3 Alternatives Sawtooth National Forest, killing substantial numbers of subalpine fir. Chemical Control 3 Recognizing 4 adelgid damage Damage depends on population density Other Reading 4 Balsam woolly adelgid was around the buds and branch nodes. Field Guide discovered in northern Idaho in All sizes of trees are attacked. 1983 feeding predominantly on but the infestations may be Management Guide Index subalpine fir and to a less extent, concentrated on the stems or in the grand fir. Since that time, it has crowns. Stem-attacked trees can die been found from the Canadian after only 2-3 years of heavy border to as for south as the infestation and without any apparent Sawtooth National Forest in Idaho. gouting. Key Points It has caused extensive mortality of In the crowns, gouts occur on It is a non- subalpine fir, especially in low- the fastest growing parts of the tree, native species elevation drainage bottoms. and on trees that have been lightly that has only Nymphs feed on the bark of stems, infested for a long time. These trees been known in branches, and twigs, and at the decline slowly, growth is reduced, Idaho since base of new shoots and buds, but and the dead and dying upper stem is 1983. -

Balsam Woolly Adelgid (Adelges Piceae)

Balsam Woolly Adelgid (Adelges piceae) Why we care: Balsam woolly adelgid (BWA) is a sap-feeding insect that attacks true fir trees, including balsam fir and Fraser fir. Repeated attacks weaken trees, cause twig gouting, kill branches and, over the course of several years, cause trees to die. What is at risk? There are nearly 1.9 billion balsam fir trees in Michigan’s forests. And, as the third- largest Christmas tree-growing state in the country, Michigan produces nearly 13.5 million fir trees each year, grown on over 11,500 acres. True fir trees, including forest, landscape and Christmas trees, are susceptible. Small (less than 1/32 nd of an inch) purplish-black adults form white, waxy “wool” covering twigs, branches and stems of infested trees (see photo). Smaller, amber-colored crawlers hatch in mid- summer. This is the mobile stage, when risk of movement by wind and wildlife is highest. The threat: BWA could be introduced into Michigan in a number of ways, including infested nursery stock, firewood, logs and vehicles. Once here, wind, birds and animals can carry this insect for miles. What could happen in Michigan? Accidentally introduced to southeastern Canada from Europe around 1900, BWA is already established in, and continues to threaten, fir trees in the Pacific Northwest, several northeastern states and the Central Atlantic states. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, for example, 95% of Fraser firs have been killed by BWA. What you can do? If you notice white, waxy material on twigs, branches or stems, or twig gouting on fir trees, do not move them! Take photos, note the location and report it! Balsam woolly adelgid-induced twig gouting on Fraser fir Balsam woolly adelgid -infested balsam fir twig William M. -

Piceae (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea: Adelgidae), Species Complex

Systematic Entomology (2021), 46, 186–204 DOI: 10.1111/syen.12456 Species delimitation and invasion history of the balsam woolly adelgid, Adelges (Dreyfusia) piceae (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea: Adelgidae), species complex NATHAN P. HAVILL1 , BRIAN P. GRIFFIN2, JEREMY C. ANDERSEN2, ROBERT G. FOOTTIT3, MATHIAS J. JUSTESEN4, ADALGISA CACCONE5, VINCENT D’AMICO6 andJOSEPH S. ELKINTON2 1USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Hamden, CT, U.S.A., 2Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, U.S.A., 3Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 4Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg C, Denmark, 5Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, U.S.A. and 6USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Newark, DE, U.S.A. Abstract. The Adelges (Dreyfusia) piceae (Ratzeburg) species complex is a taxonom- ically unstable group of six species. Three of the species are cyclically parthenogenetic [Ad. nordmannianae (Eckstein), Ad. prelli (Grossmann), and Ad. merkeri (Eichhorn)] and three are obligately asexual [Ad. piceae, Ad. schneideri (Börner), and Ad. nebro- densis (Binazzi & Covassi)]. Some species are high-impact pests of fir (Abies) trees, so stable species names are needed to communicate effectively about management. There- fore, to refine species delimitation, guided by a reconstruction of their biogeographic history, we genotyped adelgids from Europe, North America, and the Caucasus Moun- tains region with 19 microsatellite loci, sequenced the COI DNA barcoding region, and compared morphology. Discriminant analysis of principal components of microsatellite genotypes revealed four distinct genetic clusters. Two clusters were morphologically consistent with Ad. nordmannianae. One of these clusters consisted of samples from the Caucasus Mountains and northern Turkey, and the other included samples from this region as well as from Europe and North America, where Ad. -

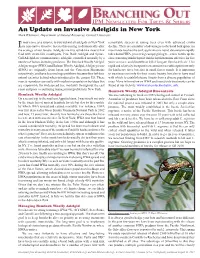

An Update on Invasive Adelgids in New York Mark Whitmore, Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University

BRANCHING OUT IPM NEWSLETTER FOR TREES & SHRUBS An Update on Invasive Adelgids in New York Mark Whitmore, Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University t may come as a surprise to you but not all adelgids in New York remarkable success at saving trees even with advanced crown Iare non-native invasive insects threatening to dramatically alter decline. There are a number of advantages to the basal bark spray: no the ecology of our forests. Adelgids are tiny aphid-like insects that insecticide touches the soil; application is rapid; dinotefuran rapidly feed with straw-like mouthparts. Pine Bark Adelgid and Spruce takes down HWA, preserving canopy giving trees time to take up the Gall Adelgid are common native adelgids, controlled naturally by a slower moving imidacloprid; imidacloprid remains effective for five number of factors including predators. The Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, years or more; and dinotefuran kills Elongate Hemlock Scale. This Adelges tsugae (HWA) and Balsam Woolly Adelgid, Adelges piceae rapid and relatively inexpensive treatment is a viable option not only (BWA) are originally from Japan and the Caucasian Mountains for landscape trees but also in small forest stands. It is important respectively, and have become huge problems because they left their to treat trees not only for their scenic beauty, but also to have seed natural enemies behind when introduced to the eastern US. These with which to establish future forests from a diverse population of insects reproduce asexually with explosive population buildups that trees. More information on HWA and insecticide treatments can be are responsible for widespread tree mortality throughout the east found at our website: www.nyshemlockinitiative.info. -

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 12 / Tuesday, January 20, 1998 / Notices 2997 Letters of Comment, Input Recorded Fully Understood

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 12 / Tuesday, January 20, 1998 / Notices 2997 letters of comment, input recorded fully understood. The spider requires plan development. The Service will during meetings). If requested under the situations of high and constant consider all information presented Freedom of Information Act by a private humidity, and the loss of forest canopy, during a public comment period prior to citizen or organization, the Service may leading to increased light and decreased approval of each new or revised provide copies of such information. moisture on the forest floor (resulting in recovery plan. The Service and other The environmental review of this desiccation of the moss mats), appears Federal agencies will also take these project will be conducted in accordance to be the major threat to its continued comments into account in the course of with the requirements of the National existence. Unless new populations are implementing approved recovery plans. Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as found or reestablished and existing The primary species considered in amended (42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.), NEPA population are maintained, this species this draft recovery plan is the spruce-fir Regulations (40 CFR 1500±1508), other will remain in jeopardy of extinction for moss spider (Microhexura montivaga). appropriate Federal laws and the foreseeable future. The Service The area of emphasis for recovery regulations, Executive Order 12996, the solicits review and comments from the actions includes the Southern National Wildlife Refuge System public on this draft plan. Appalachian Mountains of western Improvement Act of 1997, and Service DATES: Comments on this technical/ North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. -

Insertion Site Selection and Feeding of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Implications for Host-Plant Resistance

GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT PSW-GTR-240 Insertion Site Selection and Feeding of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Implications for Host-Plant Resistance K.L.F. Oten,1 A.C. Cohen,1 and F.P. Hain1 The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae), is an invasive forest pest that threatens the existence of eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.) and Carolina hemlock (T. caroliniana Engelm.) in the eastern United States. It is a small, aphid-like insect with piercing-sucking mouthparts that it uses to penetrate its host plant and feed off the xylem ray parenchyma cells (Young et al. 1995). The hemlock woolly adelgid is native to eastern Asia and northwestern North America where it feeds on, but does not kill, its host (Annand 1924, Havill et al. 2006). The mechanism of resistance and/or tolerance is unknown. The invasive population in the eastern United States was first detected near Richmond, Virginia in 1951 (Gouger 1971, Souto et al. 1996). The range of HWA in the east has since spread through the range of hemlocks, now affecting 18 states (USDA FS 2011). The mortality caused by HWA to eastern and Carolina hemlocks is tremendous. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of infested hemlocks native to the eastern United States have already vanished as a result of this exotic insect (Hale 2004, Townsend and Rieske-Kinney 2006). Moreover, the production of hemlocks for the ornamental industry, valued at $34 million between Tennessee and North Carolina alone, has been virtually eliminated (Bentz et al. 2002). Following initial infestation, a susceptible hemlock declines in health, evident by needle drop, bud abortion, and inhibition of new growth (McClure 1991).