Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Oral Evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 712 Tuesday 12 January 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 12 January 2016 Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Andrew Tyrie (Chair), Sir Paul Beresford, Mr Clive Betts, Crispin Blunt, Andrew Bridgen, Ms Harriet Harman, Meg Hillier, Huw Irranca-Davies, Dr Julian Lewis, Mr Angus Brendan MacNeil, Jesse Norman, Mr Laurence Robertson, Neil Parish, Keith Vaz, Bill Wiggin Questions 1–108 Witness: Rt Hon David Cameron MP, Prime Minister, gave evidence. Q1 Chair: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Thank you very much for coming to give evidence to the first of the Liaison Committee’s public meetings in this Session. First of all, I want to establish that you are going to continue the practice of the last Parliament and appear three times a Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, if we all agree. I thought last time it worked quite well to have three sessions: one in this bit, one between Easter and summer, and one later in the year. This idea of picking some subjects, to be determined by you, rather than going across the piece—I am happy either way, but I think it worked okay. Q2 Chair: We have a problem for this Session, because we have a bit of a backlog. We tried to get you before Christmas but that was not possible, so we would be very grateful if you could make two more appearances this Session. Mr Cameron: Yes, that sounds right—one between Easter and summer recess, and one— Q3 Chair: I think it will be two before the summer. -

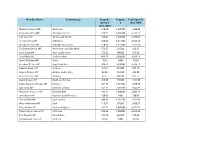

By-Election Results: Revised November 2003 1987-92

Factsheet M12 House of Commons Information Office Members Series By-election results: Revised November 2003 1987-92 Contents There were 24 by-elections in the 1987 Summary 2 Parliament. Of these by-elections, eight resulted Notes 3 Tables 3 in a change in winning party compared with the Constituency results 9 1987 General Election. The Conservatives lost Contact information 20 seven seats of which four went to the Liberal Feedback form 21 Democrats and three to Labour. Twenty of the by- elections were caused by the death of the sitting Member of Parliament, while three were due to resignations. This Factsheet is available on the internet through: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets November 2003 FS No.M12 Ed 3.1 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2003 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 By-election results: 1987-92 House of Commons Information Office Factsheet M12 Summary There were 24 by-elections in the 1987 Parliament. This introduction gives some of the key facts about the results. The tables on pages 4 to 9 summarise the results and pages 10 to 17 give results for each constituency. Eight seats changed hands in the 1987 Parliament at by-elections. The Conservatives lost four seats to Labour and three to the Liberal Democrats. Labour lost Glasgow, Govan to the SNP. The merger of the Liberal Party and Social Democratic Party took place in March 1988 with the party named the Social and Liberal Democrats. This was changed to Liberal Democrats in 1989. -

The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield In

“Not Just Supporting But Leading”: The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield in the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike By Rebecca Davies Enrolment: 00068411 Thesis submitted for Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Glamorgan February 2010. ABSTRACT The 1984-85 miners’ strike dramatically changed the face of the South Wales Valleys. This dissertation will show that the women’s groups that played such a crucial supportive role in it were not the homogenous entity that has often been portrayed. They shared some comparable features with similar groups in English pit villages but there were also qualitative differences between the South Wales groups and their English counterparts and between the different Welsh groups themselves. There is evidence of tensions between the Welsh groups and disputes with the communities they were trying to assist, as well as clashes with local miners’ lodges and the South Wales NUM. At the same time women’s support groups, various in structure and purpose but united in the aim of supporting the miners, challenged and shifted the balance of established gender roles The miners’ strike evokes warm memories of communities bonding together to fight for their survival. This thesis investigates in detail the women involved in support groups to discover what impact their involvement made on their lives afterwards. Their role is contextualised by the long-standing tradition of Welsh women’s involvement in popular politics and industrial disputes; however, not all women discovered a new confidence arising from their involvement. But others did and for them this self-belief survived the strike and, in some cases, permanently altered their own lives. -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event. -

The Curious Case of Ted Dexter and Cardiff South East

n 1964 the electorate of Cardiff dismal levels of support that was common as the Conservative candidate and give South East faced the unusual in coalfield, or ‘Valleys’, constituencies, the impression that he was perhaps I situation of having the England although the general Welsh suspicion encouraged to do so by those at the top cricket captain as its Conservative about Conservatism was undoubtedly of the Association in favour of a ‘big parliamentary candidate. Edward present in parts of Cardiff as well.3 name’ alternative. Reconstructing events R. Dexter, better known as Ted, may Nonetheless, at the 1959 general election, is made more difficult by the fact that no have failed to defeat Labour’s incumbent in a straight fight with the Conservative meeting of the constituency executive James Callaghan, but the result was far Party, Callaghan was re-elected to committee was held for eight months from the foregone conclusion as which Parliament with a majority of only 868 encompassing the time that Roberts it has sometimes subsequently been in a contest that saw on the Conservative resigned.8 The sense that the Chairman dismissed. The constituency was then side ‘more work, more helpers, more of the Association, G.V. Wynne-Jones, thought of as ‘super marginal’.1 His failure keenness and more enthusiasm … than was scheming behind closed doors is only has thus meant that, in hindsight, Dexter ever before’.4 Callaghan’s Conservative reinforced by his rather limp excuse – in was considered by many to have been a opponent on that occasion was a locally response to complaints about the lack of disastrous parliamentary candidate. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Palimpsestuous Meanings in Art Novels

‘An Unconventional MP’: Nancy Astor, public women and gendered political culture How to Cite: Blaxland, S 2020 Welsh Women MPs: Exploring Their Absence. Open Library of Humanities, 6(2): 26, pp. 1–35. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/olh.548 Published: 20 November 2020 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Open Library of Humanities, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. Sam Blaxland, ‘Welsh Women MPs: Exploring Their Absence’ (2020) 6(2): 26 Open Library of Humanities. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/olh.548 ‘AN UNCONVENTIONAL MP’: NANCY ASTOR, PUBLIC WOMEN AND GENDERED POLITICAL CULTURE Welsh Women MPs: Exploring Their Absence Sam Blaxland Department of History, Swansea University, Swansea, UK [email protected] Between 1918 and the end of the 1990s, Wales had only four women members of Parliament. This article concentrates largely on that period, exploring who these women were, and why there were so few of them. It analyses the backgrounds and careers of Megan Lloyd George, Eirene White and Dorothy Rees, the first three women to be elected, arguing that two of them were aided into their positions by their exclusive social connections and family backgrounds. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

The Prime Minister, HC 1393

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: The Prime Minister, HC 1393 Wednesday 18 July 2018 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 18 July 2018. Watch the meeting Members present: Dr Sarah Wollaston (Chair); Hilary Benn; Chris Bryant; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Mary Creagh; Lilian Greenwood; Sir Bernard Jenkin; Norman Lamb; Dr Julian Lewis; Angus Brendan MacNeil; Dr Andrew Murrison; Neil Parish; Tom Tugendhat. Questions 1-133 Witnesses I: Rt Hon Theresa May, Prime Minister. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Rt Hon Theresa May, Prime Minister. Chair: Good afternoon, and thank you for coming. For those following from outside the room, we will cover Brexit to start with for the first hour, and then we will move on to the subjects of air quality, defence expenditure, the restoration and renewal programme here and, if we have time, health and social care. We will start the session with Hilary Benn, the Exiting the European Union Committee Chair. Q1 Hilary Benn: Good afternoon, Prime Minister. Given the events of the last two weeks, wouldn’t it strengthen your hand in the negotiations if you put the White Paper to a vote in the House of Commons? The Prime Minister: What is important is that we have set out the Government’s position and got through particularly important legislation in the House of Commons. Getting the European Union (Withdrawal) Act on the statute book was a very important step in the process of withdrawing from the European Union. We have published the White Paper, and we have begun discussing it at the EU level. -

Section 1: a Minister Proposed, 1941-51

Defending the Constitution: the Conservative Party & the idea of devolution, 1945-19741 In retrospect, the interwar years represented a golden age for British Conservatism. As the Times remarked in 1948, during the ‘long day of Conservative power which stretched with only cloudy intervals between the two world wars’ the only point at issue was how the party might ‘choose to use the power that was almost their freehold’.2 Nowhere was this sense of all-pervading calm more evident than in the sphere of constitutional affairs. The settlement of the Irish question in 1921-22 ensured a generation of relative peace for the British constitution.3 It removed from the political arena an issue that had long troubled the Conservatives’ sense of ‘civic nationalism’ - their feeling that the defining quality of the ‘nation’ to which they owed fealty was the authority of its central institutions, notably parliament and the Crown – and simultaneously took the wind from the sails of the nationalist movements in Wales and Scotland.4 Other threats to the status quo, such as Socialism, were also kept under control. The Labour Party’s failure to capture an outright majority of seats at any inter-war election curbed its ability to embark on the radical reshaping of society that was its avowed aim, a prospect which, in any case, astute Tory propagandising ensured was an unattractive proposition to most people before the second world war.5 1 I would like to record my thanks to Dr James McConnel, Ewen Cameron and Stuart Ball for their input to this chapter. -

Formal-Minutes-Liaison-Committee

House of Commons Liaison Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017–19 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2017–19 1 Formal Minutes of the Liaison Committee, Session 2017–19 MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 Members present: Hilary Benn Norman Lamb Mr Clive Betts Dr Julian Lewis Chris Bryant Angus Brendan MacNeil Sir William Cash Ian Mearns Damian Collins Mrs Maria Miller Yvette Cooper Nicky Morgan Mary Creagh Robert Neill David T C Davies Neil Parish Frank Field Rachel Reeves Lilian Greenwood Tom Tugendhat Harriet Harman Bill Wiggin Meg Hillier Pete Wishart Mr Bernard Jenkin Dr Sarah Wollaston Helen Jones 1. Declarations of Interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix). 2. Election of Chair Dr Sarah Wollaston was called to the Chair. Resolved, That the Chair report her election to the House. 3. Evidence from the Prime Minister The Committee considered this matter. 4. National Policy Statements Sub-Committee Ordered, That a National Policy Statements Sub-Committee be appointed (Standing Order No. 145(6)). Ordered, That Dr Sarah Wollaston and Mary Creagh be members of the National Policy Statements Sub-Committee in addition to those members of the committee who are for the time being members of the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Communities and Local Government, Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2 Liaison Committee: Formal Minutes 2017–19 Transport and Welsh Affairs Committees, and that Dr Sarah Wollaston be Chair of the National Policy Statements Sub-Committee (Standing Order No. 145(7)(a)(ii)). Resolved, That the Sub-Committee recommends that, pursuant to Standing Order No.