Africa's Single Aviation Market: the Progress So

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Enhancing Africa Tourism Growth Through Aviation – Tourism Regulatory Convergence

Enhancing Africa Tourism Growth through Aviation – Tourism Regulatory Convergence By Ray’ Mutinda, Ph.D Mt Kenya University School of Hospitality, Travel and Tourism UNECA CONSULTANT Drivers… Africa has witnessed a • Efforts to liberalize her aviation industry sustained growth in her air (particularly the outcomes of the Yamoussoukro transportation sector, Decision of 1999) rising by 6.6 % over the • A number of airlines from the U.S., Europe and last decade, making the Africa have continued to expand operations continent the second across the continent. fastest growing region • The growing alliances with counterpart regions globally after Asia. • The growth of LCCs in Africa (though not widely spread, with the current composition being in six countries-South Africa, Kenya, Egypt, Morocco, Traffic to, from, and within Tanzania, Zimbabwe) Africa is projected to grow • Accelerated economic growth (by the close of by about 6 percent per 2014, 25 African countries had attained middle- year for the next 20 years income status)- resulting in an economy based on (Boeing’s long term rising incomes, consumption, employment, and forecast 2014-2033) productivity (Boeing, 2014) • Growth in the middle class- 313 mn by 2011 (AfDB)-. Efforts towards the liberalization of Africa’s aviation industry… The aspirations for an integrated intra-regional air transportation has always existed in Africa… 1961 Yaoundé Provided for the creation of Air Afrique, the assignment of the Treaty international traffic rights of each signatory to Air Afrique and the definition -

Mali's Infrastructure

COUNTRY REPORT Mali’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective Cecilia M. Briceño-Garmendia, Carolina Dominguez and Nataliya Pushak JUNE 2011 © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Single African Air Transport Market Is Africa Ready?

Single African Air Transport Market Is Africa ready? May 2018 Single African Air Transport Market | Is Africa ready? Single African Air Transport Market | Is Africa ready? Executive Summary “In 2017, more than 4 billion The liberalisation of civil aviation in Africa as an impetus to the Continent’s economic integration agenda led to the launch of the Single African Air passengers used aviation to Transport Market (SAATM). The Open Sky agreement, originally signed by 23 out reunite with friends and loved of 55 Member States, aimed to create a single unified air transport market in Africa. ones, to explore new worlds, to do business, and to take advantage of Africa is considered a growing aviation market with IATA forecasting a 5.9% year-on-year growth in African aviation over the next 20 years, with passenger opportunities to improve themselves. numbers expected to increase from 100m to more than 300m by 2026 and Aviation truly is the business of SAATM is a way to tap into this market. The benefits of SAATM to African Countries include job creation, growth in trade resulting to growth in GDP and freedom, liberating us from the lower travel costs resulting to high numbers of passengers. However, is Africa restraints of geography to lead better ready for a Single African Air Transport Market? lives. In Deloitte’s opinion, SAATM needs to consider various aspects in regards to ownership and effective control, eligibility, infrastructure, capacity and frequency De Juniac, IATA (2018) of flights. In this situation, we turn to various international treaties as guideposts where these Open Skies agreement have been done relative success. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

The Aeronautical and Space Industries of the Community Compared with Those of the United Kingdom and - the United States

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES The aeronautical and space industries of the Community compared with those of the United Kingdom and - the United States GENERAL REPORT Volume 4 COMPETITION INDUSTRY - 1971 - 4 I Survey carried out on behalf of the Commission of the European Communities (Directorate- General for Industry) Project coordinator: Mr Felice Calissano, with the assistance of Messrs Federico Filippi and Gianni Jarre of Turin Polytech nical College and Mr Francesco Forte of the University of Turin SORIS Working Group : Mr Ruggero Cominotti Mr Ezio Ferrarotti Miss Donata Leonesi Mr Andrea Mannu Mr Jacopo Muzio Mr Carlo Robustelli Interviews with government agencies and private companies conducted by : Mr Felice Calissano Mr Romano Catolla Cavalcanti Mr Federico Filippi Mr Gianni Jarre Mr Carlo Robustelli July 1969 I No. 7042 SORIS spa Economic studies, market research 11, via Santa Teresa, Turin, Italy Tel. 53 98 65/66 The aeronautical and space industries of the Community compared \ with those of the United Kingdom and the United States STUDIES Competition Industry No.4 BRUSSELS 1971 THE AERONAUTICAL AND SPACE INDUSTRIES OF THE COMMUNITY COMPARED WITH THOSE OF THE UNITED KINGDOM AND THE UNITED STATES VOLUME 1 The aeronautical and space research and development VOLUME 2 The aeronautical and space industry VOLUME 3 The space activities VOLUME 4 The aeronautical market VOLUME 5 Technology- Balance of payments The role of the aerospace industry in the economy Critical assessment of the results of the survey CHAPTER 3 The aeronautical market ! Contents PART 1 THE MARKET FOR CIVIL AIRCRAFT 1 • INTRODUCTION 675 2. TYPES OF AIRCRAFT 675 NUMBERS OF AIRCRAFT 680 3.1 Total Number 680 3.2 Breakdown by Type of Aircraft and by Country 688 4. -

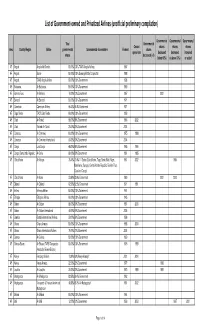

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Improving Flight Connections in Ecowas Region

IMPROVING FLIGHT CONNECTIONS IN ECOWAS REGION Presented by Dr. Paul-Antoine Marie GANEMTORE Head of Air Transport Unit Infrastructure Department ECOWAS COMMISSION 1 Presentation Outline CHALLENGES OF AIR TRANSPORT COMMUNITY AIR TRANSPORT LEGAL FRAMEWORK WAY FORWARD CHALLENGES OF AIR TRANSPORT 3 CONTEXT CREATION 28 May, 1975 in Lagos, Nigeria, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) OBJECTIVE Co-operation and integration to support growth in regional trade and free movement, leading to establishment of an Economic Union in West Africa Article 32 –f: “Encourage co-operation in flight-scheduling, leasing of aircraft and granting and joint use of fifth freedom rights to airlines of the region” 15 MEMBER STATES Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone & Togo GENERAL DATA 328 Million inhabitants in 5,1 Million Km2 surface area 534 Billion USD GDP Mineral Resources (Petrol, Gas, Gold, Uranium, Phosphate,...) & Agriculture Resources(Cocoa, Coffee, Sugar, Cotton, Rubber, Wood...) ROLE OF ECOWAS COMMISSION Coordination and harmonization of policy, programmes, actions, projets, as entrhrusted by the member States….. 4 2013 ECOWAS AIR TRANSPORT MARKET YEAR 2013 PAX CARGO AIRCRAFT POPULATION SURFACE GDP m Ton mvts m Km2 Billions BENIN 476,704 7,616 12,309 10,300,000 112,760 8.30 BURKINA FASO 523,355 7,011 9,936 17,800,000 273,600 12.2 CAPE VERDE 1,957,747 3,061.5 28,702 0,530,000 4,030 1.9 COTE D’IVOIRE 1,152,887 17,548 18,195 -

International Air Carrier Liability for Death & Personal Injury: to Infinity and Beyond

International Air Carrier Liability for Death & Personal Injury: To Infinity and Beyond by Paul Stephen Dempsey Tomlinson Professor Emeritus of Law Director Emeritus , Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2017 by Paul Stephen Dempsey To what damages do the Warsaw regime and the Montreal Convention apply? Carrier liability for: . Passenger death, bodily injury or delay; . Air freight and baggage loss, damage, or delay; . In international carriage, for compensation. The Convention does not address liability of the airport, ANSP or aircraft manufacturers, or liability for surface damage. What is international air carriage? The place of departure and place of destination are: both in "Warsaw System" or M99 States or in the same "Warsaw System" or M99 State with an agreed stopping place in another State And both States have ratified a common liability Convention or Protocol. You look for the “highest common denominator” treaty between the origin and destination State. In round-trip transportation, the origin and destination State are the same. Which Legal Regime Applies? . The original Warsaw Convention of 1929, unamended; . The Warsaw Convention as amended by Montreal Protocol No. 1 of 1975; . The Warsaw Convention as amended by the Hague Protocol of 1955; . The Warsaw Convention as amended by the Hague Protocol and Montreal Protocol No. 2 of 1975; . The Warsaw Convention as amended by the Hague Protocol and Montreal Protocol No. 4 of 1975; . The Montreal Convention of 1999, or . Domestic law, if it is deemed that the transportation falls outside the conventional international law regime, or if the two relevant States have failed to ratify the same liability convention. -

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aerom

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aeromas African Intl Air Afrique #1 Air Afrique #2 Air Algerie Air Atlas Air Austral Air Botswana Air Brousse Air Cameroon Air Cape Air Carriers Air Djibouti Air Centrafique Air Comores Air Congo Air Gabon Air Gambia Air Ivoire Air Kenya Aviation Airlink Air Lowveld Air Madagascar Air Mahe Air Malawi Air Mali Air Mauritanie Air Mauritius Air Namibia Box 2 Air Rhodesia Air Senegal Air Seychelles Air Tanzania Air Zaire Air Zimbabwe Aircraft Operating Co. Alliances Avex Avia Bechuanaland Natl. Bellview Bop Air Cameroon Airlines Campling Bros. Capital Air Caspair / Caspar Cata Catalina Safari Central African Airways Christowitz Clairways Command Airways Commercial Air Service Copperbelt Court Heli DAS – Dairo Desert Airways Deta DTA Angola East African Airways Corp Eastern Air Zambia Egypt Air Elders Colonial Box 3 Ethiopian Federal Airlines Sudan Flite Star Gambia Airways German Ghana Airways Guinea Hold – Trade Hunting Clan Imperial Inter Air International Air Kitale Zaire Katanga Kenya Airways Lam Lara Leopard Air Lana Lesotho Airways Liverian National Libyan Arab Magnum MISR Namib Air National Nigeria Airways North African Airlines (Tunisia) Phoenix Protea Pyramid RAC – Rhodesia Regie Malgache R.A.N.A Rhodesian Air Service Box 4 Rossair Royal Air Maroc Royal Swazi Ruac Sa Express Safair Safari Air Svcs Saide Sata Algeria SATT Scibe Shorouk Sierra Leone Airlines Skyways Sobelair South African Aerial Transport Somali Airlines -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank IE L W FOR OFFI('IAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 2290-SE Public Disclosure Authorized SENEGAL STAFF APFPRAISAL REPORT SECOND AVIATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized February 2, 1979 Public Disclosure Authorized Western Africa Projects Department Ports, Railways, & Aviation Division This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currency Unit: - CFA Francs (CFAF) US$1.00 - CFAF 220 CFAF 1 million. - US$4,545 FISCAL YEAR Government (Borrower) July 1 - June 30 ASECNA January 1 - December 31 SYSTEM OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES: Metric 1 meter (m) 2 3.28 feet (ft) I square meter (5 ) 10.8 square feet (sq.) 1 cubic meter (m ) 35.3 cubic feet (cu ft) 1 kilometer (km) 2 0.620 mile (mi) 1 square kilometer (km ) 0.386 square mile (sq. mi.) I hectare (ha) 2.47 acres 1 metric ton (t) 2,204 pounds (lb) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ASECNA - Agence pour la Securite de la Navigation Aerienne en Afrique et a Madagascar DAC - Directorate of Civil Aviation Dakar Airport - Dakar-Yoff International Airport DSP - Directorate of Studies and Programming GDP - Gross Domestic Product ME - Ministry of Equipment VASIS - Visual Approach Slope Indicator System VOR - Very High Frequency Omni-Range FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY SENEGAL STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT SECOND AVIATIONF PROJECT Table of Contents Page No. I. THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ................................... 1 A. Economic Setting ............................. 1 B. The Transport System .......................... .1 C. Transport Planning and Coordination ............. -

1 Attribution-Noncommercial

Downloaded from: http://bucks.collections.crest.ac.uk/ The Future for African Air Transport: Learning from Ethiopian Airlines Nadine Meichsner1, John F. O’Connell1,2,*, David Warnock-Smith3 This document is protected by copyright. It is published with permission and all rights are reserved. Usage of any items from Buckinghamshire New University’s institutional repository must follow the usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the institutional repository is subject to Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Please note that you must also do the following; • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. If you need further guidance contact the Research Enterprise and Development Unit [email protected] 1 The Future for African Air Transport: Learning from Ethiopian Airlines 1 1,2,* 3 Nadine Meichsner , John F. O’Connell , David Warnock-Smith 1 Centre for Air Transport, Cranfield University, Bedford, MK43 0AL, UK 2 Centre for Aviation Research, School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH, UK 3 School of Aviation and Security, Buckinghamshire New University, High Wycombe campus, Queen Alexandra Road, High Wycombe, HP11 2JZ * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The African air transport market has been a laggard in development, remaining encircled by a plethora of problematic issues that curtailed its expansion and prosperity for decades.