1 Attribution-Noncommercial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Annual Report 2004/05

ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES Annual Report 2004-05 WWW.ETHIOPIANAIRLINES.COM ANNUAL REPORT 2004-05 building CONTENTS on the FUTURE Management Board of Ethiopian Airlines .................................. 2 CEO’s Message............................................................................................. 3 Ethiopian Airlines Management Team ......................................... 4 Embarking on a long-range reform I. Investing for the future Continent .................................... 5 II. Continuous Change .............................................................. 5 III. Operations Review ............................................................... 5 IV. Measures to Enhance Profitability .................................. 7 V. Human Resource Development ....................................... 10 VI. Fleet Planning and Financing .......................................... 11 VII. Information Systems .......................................................... 11 VIII. Tourism Promotion ............................................................ 11 IX. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Measures ....... 12 Finance ............................................................................................................. 13 Auditors Report and Financial Statements ................................ 22 Domestic Route Map .............................................................................. 40 Ethiopian Airlines Offices ...................................................................... 41 International Route Map ...................................................................... -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

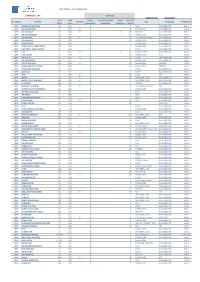

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

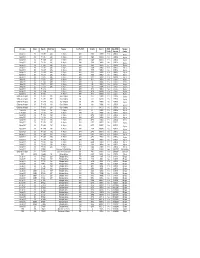

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry 11.1 AIR TRANSPORT The main objective of the decision was IN AFRICA the gradual liberalization of scheduled and non-scheduled intra-African air services, The poor state of land transport infrastructure abolishing limits on the capacity and and freight and passenger services in much frequency of international air services within of Africa appears to offer a promising Africa, liberalizing fares and universally opportunity for the further development of air granting traffi c rights up to the ”fi fth freedom transport services throughout the continent. At of the air.”2 Signatory states were obliged to this stage, the key policy issues for Zimbabwe ensure the fair opportunity to compete on a are the ways it can benefi t from the ongoing nondiscriminatory basis. A monitoring body liberalization of civil aviation within the was to supervise and implement the decision, continent called for in the Yamoussoukro and an African air transport executing agency Decision of 1999 and the actions it needs to was to ensure fair competition. Even though take in the decade ahead to ensure that the the decision was a pan-African agreement benefi ts of liberalization are realized. to which most African states are bound, the parties decided that it should be implemented 11.1.1 The Yamoussoukro Decision by separate regional economic organizations. The monitoring body has met only a few Over the past three decades, much of the times. Competition rules and arbitration world has moved from a strictly regulated air procedures are still pending. A recent World transport industry to a more liberalized one. -

UPDATED ON: 18-03-2019 STATION AIRLINE IATA CODE AWB Prefix ON-LINE CARGO HANDLING FREIGHTER RAMP HANDLING RAMP LINEHAUL IMPORT

WFS CARGO - CUSTOMERS LIST DENMARK - CPH SERVICES UPDATED ON: 18-03-2019 IATA AWB CARGO FREIGHTER RAMP RAMP IMPORT STATION AIRLINE ON-LINE GSA TRUCKING TERMINAL CODE Prefix HANDLING HANDLING LINEHAUL EXPORT CPH AMERICAN AIRLINES AA 001 X E NAL WALLENBORN HAL 1 CPH DELTA AIRLINES DL 006 X X I/E PROACTIVE WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH AIR CANADA AC 014 X X X I/E HWF DK WALLENBORN HAL 1 CPH UNITED AIRLINES UA 016 X I/E NORDIC GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH LUFTHANSA LH 020 X X I/E LUFTHANSA CARGO WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH US AIRWAYS US 037 X I/E NORDIC GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH DRAGON AIR XH 043 X I NORDIC GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR 044 X E CARGOCARE WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH LAN CHILE - LINEA AEREA LA 045 X E KALES WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH TAP TP 047 X X x I/E SCANPARTNER WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH AER LINGUS EI 053 X I/E NORDIC GSA N/A HAL1 CPH AIR France AF 057 X X I/E KL/AF KIM JOHANSEN HAL2 CPH AIR SEYCHELLES HM 061 X E NORDIC GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH CZECH AIRLINES OK 064 X X I/E AviationPlus VARIOUS HAL1 CPH SAUDI AIRLINES CARGO SV 065 X I/E AviationPlus VARIOUS HAL1 CPH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES ET 071 X E KALES WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH GULF AIR GF 072 X E KALES WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH KLM KL 074 X X I/E KL/AF JDR HAL2 CPH IBERIA IB 075 X X I/E UNIVERSAL GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES ME 076 X X E UNIVERSAL GSA WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH EGYPTAIR MS 077 X E HWF DK WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH BRUSSELS AIRLINES SN 020 X X I/E LUFTHANSA CARGO JDR HAL1 CPH SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS SA 083 X E CARGOCARE WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH AIR NEW ZEALAND NZ 086 X E KALES WALLENBORN HAL1 CPH AIR -

Download Ethiopian Fact Sheet April 2017

VICTORIA FALLS Ethiopian Airlines Factsheet - April 2017 OSLO ANTANANARIVO Overview Ethiopian Airlines (Ethiopian) is the leading and most profitable airline in Africa. In 2014 IATA ranked Ethiopian as the largest airline in Africa in revenue and profit. Over the past seven decades, Ethiopian has been a pioneer of African aviation as an aircraft technology leader. It all started with a military surplus C-47, leading the way with the first Jet service in the continent in the early 60’s to the first B-767 in the mid 80’s, to the first African B-787 Dreamliner in 2012 and the first African Airbus A-350 in 2016. Ethiopian joined Star Alliance, the world’s largest Airline network, in December 2011. Ethiopian is currently implementing a 15-year strategic plan called Vision 2025 that will see it become the leading airline group in Africa with seven strategic business units. Ethiopian is a multi-award winning airline, including SKYTRAX and Passenger Choice Awards in 2015, and has been registering an average growth of 25% per annum for the past ten years. Ethiopian Background Information Founded E December 21, 1945 Starting date of operation E April 08, 1946 Ownership E Government of Ethiopia (100%) Head Office E Bole International Airport, P.O. Box 1755 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Fax: (+ 251)11661 1474 Reservations E Tel: (+251) 11 665 6666 Website E http://www.ethiopianairlines.com Group Chief Executive Officer E Mr. Tewolde GebreMariam Fleet Summary Aircraft Inventory: 87 Fleet on order: 47 Average age of aircraft: 5 years Passenger aircraft Airbus -

(AIM: FJET) Final Results for the Year to 31 December 2016 30 May 2017 Fa

fastjet Plc ("fastjet" or the “Company”) (AIM: FJET) Final results for the year to 31 December 2016 30 May 2017 fastjet, the low-cost African airline, announces its audited final results for the year ended 31 December 2016. The table below shows the financial performance of the fastjet Group’s continuing activities. 2016 2015 US$ US$ Revenue 68.5m 65.1m Group Operating loss (63.9)m (37.9)m Loss from continuing activities before tax (65.8)m (35.9)m Loss from continuing activities after tax (66.0)m (36.2)m Profit/(loss) from discontinued activities after tax 18.0m 14.3m Loss for the year after tax (48.0)m (21.9)m Loss per share from continuing activities (0.84) (0.71) Cash balance at year end 3.6m 28.9m Strategic highlights ● Nico Bezuidenhout appointed CEO on 1 August 2016. ● Stabilisation Plan initiated comprising: o Major cost reductions o Fleet transition to smaller aircraft o Head office relocation to Johannesburg o Revenue initiatives including route rationalisation ● Successful capital fundraising of approximately US$20.0m before expenses in August 2016 ● Strategic and operational partnership with Solenta Aviation Holdings concluded in January 2017 providing 3 E145 aircraft at reduced lease rates and Solenta acquiring a 28% shareholding in fastjet. ● Additional capital raise of approximately US$28.8m before expenses in January 2017, reflecting optimism in the strategic outlook for fastjet Operational highlights ● Named Africa’s Leading Low-Cost Airline 2016 at the World Travel Awards ● Revenues increased by 5% to US$68.5m (2015: -

(Eu) 2015/ 1014

27.6.2015 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 162/65 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2015/1014 of 25 June 2015 amending Regulation (EC) No 474/2006 establishing the Community list of air carriers which are subject to an operating ban within the Community (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005 of the European Parliament and the Council of 14 December 2005 on the establishment of a Community list of air carriers subject to an operating ban within the Community and on informing air passengers of the identity of the operating carrier, and repealing Article 9 of Directive 2004/36/CE (1), and in particular Article 4(2) thereof, Whereas: (1) Commission Regulation (EC) No 474/2006 (2) established the list of air carriers which are subject to an operating ban within the Union, referred to in Chapter II of Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005. (2) In accordance with Article 4(3) of Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005, some Member States and the European Aviation Safety Agency (‘EASA’) communicated to the Commission information that is relevant in the context of updating that Union list. Relevant information was also communicated by certain third countries. On the basis of that information and the verifications carried out by the Commission, the Union list should now be updated. (3) The Commission informed all air carriers concerned, either directly or through the authorities responsible for their regulatory oversight, about the essential facts and considerations which would form the basis for a decision to impose on them an operating ban within the Union or to modify the conditions of an operating ban imposed on an air carrier which is included in the Union list. -

2.2 Togo Aviation

2.2 Togo Aviation Key airport information may also be found at: http://worldaerodata.com/ In Togo, the National Agency of Civil Aviation of Togo (ANAC-TOGO) created by the law n° 2007-007 of January 22nd, 2007 bearing the code of the civil aviation, is the authority in charge of the implementation of international standards and recommendations and the implementation of the Togolese State's civil aviation policy. In this capacity, ANAC-TOGO is responsible for: the execution of the State's civil aviation policy the negotiation of international agreements in the context of special powers and warrants conferred by the State the development of a technical regulation of civil aviation in accordance with the standards of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) the development and implementation of the Civil Aviation and Air Transport Strategy in accordance with the National Priority Guidelines the monitoring of the application of the national regulations in force and of the international conventions signed and ratified by Togo about safety, security and facilitation the management of all traffic rights resulting from air agreements signed by the State the coordination and supervision of all aeronautical and airport activities and the monitoring of the activities of international and regional organizations working in the field of civil aviation monitoring the management of the land assets of the State assigned to civil aviation monitoring of the State's commitments in the field of civil aviation The Agency represents the State in the commissions, committees, assemblies and councils whose object relates to its missions. ASKY Airlines serves 19 scheduled destinations throughout West and Central Africa from its hub at Lomé airport. -

Enhancing Africa Tourism Growth Through Aviation – Tourism Regulatory Convergence

Enhancing Africa Tourism Growth through Aviation – Tourism Regulatory Convergence By Ray’ Mutinda, Ph.D Mt Kenya University School of Hospitality, Travel and Tourism UNECA CONSULTANT Drivers… Africa has witnessed a • Efforts to liberalize her aviation industry sustained growth in her air (particularly the outcomes of the Yamoussoukro transportation sector, Decision of 1999) rising by 6.6 % over the • A number of airlines from the U.S., Europe and last decade, making the Africa have continued to expand operations continent the second across the continent. fastest growing region • The growing alliances with counterpart regions globally after Asia. • The growth of LCCs in Africa (though not widely spread, with the current composition being in six countries-South Africa, Kenya, Egypt, Morocco, Traffic to, from, and within Tanzania, Zimbabwe) Africa is projected to grow • Accelerated economic growth (by the close of by about 6 percent per 2014, 25 African countries had attained middle- year for the next 20 years income status)- resulting in an economy based on (Boeing’s long term rising incomes, consumption, employment, and forecast 2014-2033) productivity (Boeing, 2014) • Growth in the middle class- 313 mn by 2011 (AfDB)-. Efforts towards the liberalization of Africa’s aviation industry… The aspirations for an integrated intra-regional air transportation has always existed in Africa… 1961 Yaoundé Provided for the creation of Air Afrique, the assignment of the Treaty international traffic rights of each signatory to Air Afrique and the definition -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A.