Ancient Festivals and Their Cultural Contribution to Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Names

Planet Names How do planets and their moons get their names? With the exception of Earth, all of the planets in our solar system have names from Greek or Roman mythology. This tradition was continued when Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto were discovered in more modern times. Mercury (Hermes) is the god of commerce, travel and thievery in Roman mythology. The planet probably received this name because it moves so quickly across the sky. Venus (Aphrodite) is the Roman goddess of love and beauty. The planet is aptly named since it makes a beautiful sight in the sky, with only the Sun and the Moon being brighter. Earth (Gaia) is the only planet whose English name does not derive from Greek/Roman mythology. The name derives from Old English and Germanic. There are, of course, many other names for our planet in other languages. Jupiter (Zeus) was the King of the Gods in Roman mythology, making the name a good choice for what is by far the largest planet in our solar system Mars (Ares) is the Roman god of War. The planet probably got this name due to its red color. Jupiter was the King of the Gods in Roman mythology, making the name a good choice for what is by far the largest planet in our solar system. Saturn (Cronus) is the Roman god of agriculture. Uranus is the ancient Roman deity of the Heavens, the earliest supreme god. Neptune (Poseidon), was the Roman god of the Sea. Given the beautiful blue color of this planet, the name is an excellent choice! Pluto (Hades) is the Roman god of the underworld in Roman mythology. -

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 History of Rome You Will Find in This Packet

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 A e History of Rome A You will find in this packet three different readings. 1) Augustus’ autobiography. which he had posted for all to read at the end of his life: the Res Gestae (“Deeds Accomplished”). 2) A few passages from Vergil’s Aeneid (the epic telling the story of Aeneas’ escape from Troy and journey West to found Rome. The passages from the Aeneid are A) prophecy of the glory of Rome told by Jupiter to Venus (Aeneas’ mother). B) A depiction of the prophetic scenes engraved on Aeneas’ shield by the god Vulcan. The most important part of this passage to read is the depiction of the Battle of Actium as portrayed on Aeneas’ shield. (I’ve marked the beginning of this bit on your handout). Of course Aeneas has no idea what is pictured because it is a scene from the future... Take a moment to consider how the Battle of Actium is portrayed by Vergil in this scene! C) In this scene, Aeneas goes down to the Underworld to see his father, Anchises, who has died. While there, Aeneas sees the pool of Romans waiting to be born. Anchises speaks and tells Aeneas about all of his descendants, pointing each of them out as they wait in line for their birth. 3) A passage from Horace’s “Song of the New Age”: Carmen Saeculare Important questions to ask yourself: Is this poetry propaganda? What do you take away about how Augustus wanted to be viewed, and what were some of the key themes that the poets keep repeating about Augustus or this new Golden Age? Le’,s The Au,qustan Age 195. -

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

Reconstructing the Lenaia

The Post Hole Issue 42 Reconstructing the Lenaia Peter Swallow 1 1 School of Classics, Swallowgate, Butts Wynd, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9AL Email: [email protected] The best-known of the Athenian dramatic festivals is the City Dionysia; a huge civic festival which took place in the Greek month of Elaphebolion, which equates to our late March (Csapo and Williams 1998, 105) and attracted audiences from all over Greece. However, Greek drama was not confined to the City Dionysia (or even to Athens). A number of smaller festivals included dramatic performances, many of which took place on a smaller scale amid rural Attic demes (Haigh 1907, 29)1. Meanwhile, the polis-wide Lenaia was celebrated in the Athenian month of Gamelion, which is approximate to our January. Details on the festival are scant, but with careful investigation we can begin to build up a bigger picture. Two poets presented a pair of tragedies at the Lenaia (compared to three poets with trilogies at the City Dionysia), but later the number of pairs was increased to three (Csapo and Slater 1998, 136f, III.74-III.75). There is no evidence to suggest that any satyr plays were performed. During Aristophanes’ career, three comedies were performed (Pickard-Cambridge 1973, 25), but a list of Lenaian comedies performed in 285/4 indicates that there were five (Csapo and Slater 1998, 137, III.77). Csapo and Slater (1998, 124) reiterate “the usual handbook dogma that five comedies were regularly produced at the Lenaea except during the Peloponnesian War” but equally, we might hypothesise that the number started out as three regardless of the war, and was later increased to five. -

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Flowers in Greek Mythology

Flowers in Greek Mythology Everybody knows how rich and exciting Greek Mythology is. Everybody also knows how rich and exciting Greek Flora is. Find out some of the famous Greek myths flower inspired. Find out how feelings and passions were mixed together with flowers to make wonderful stories still famous in nowadays. Anemone:The name of the plant is directly linked to the well known ancient erotic myth of Adonis and Aphrodite (Venus). It has been inspired great poets like Ovidius or, much later, Shakespeare, to compose hymns dedicated to love. According to this myth, while Adonis was hunting in the forest, the ex- lover of Aphrodite, Ares, disguised himself as a wild boar and attacked Adonis causing him lethal injuries. Aphrodite heard the groans of Adonis and rushed to him, but it was too late. Aphrodite got in her arms the lifeless body of her beloved Adonis and it is said the she used nectar in order to spray the wood. The mixture of the nectar and blood sprang a beautiful flower. However, the life of this 1 beautiful flower doesn’t not last. When the wind blows, makes the buds of the plant to bloom and then drifted away. This flower is called Anemone because the wind helps the flowering and its decline. Adonis:It would be an omission if we do not mention that there is a flower named Adonis, which has medicinal properties. According to the myth, this flower is familiar to us as poppy meadows with the beautiful red colour. (Adonis blood). Iris: The flower got its name from the Greek goddess Iris, goddess of the rainbow. -

Who Was Protagoras? • Born in Abdêra, an Ionian Pólis in Thrace

Recovering the wisdom of Protagoras from a reinterpretation of the Prometheia trilogy Prometheus (c.1933) by Paul Manship (1885-1966) By: Marty Sulek, Ph.D. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy For: Workshop In Multidisciplinary Philanthropic Studies February 10, 2015 Composed for inclusion in a Festschrift in honour of Dr. Laurence Lampert, a Canadian philosopher and leading scholar in the field of Nietzsche studies, and a professor emeritus of Philosophy at IUPUI. Adult Content Warning • Nudity • Sex • Violence • And other inappropriate Prometheus Chained by Vulcan (1623) themes… by Dirck van Baburen (1595-1624) Nietzsche on Protagoras & the Sophists “The Greek culture of the Sophists had developed out of all the Greek instincts; it belongs to the culture of the Periclean age as necessarily as Plato does not: it has its predecessors in Heraclitus, in Democritus, in the scientific types of the old philosophy; it finds expression in, e.g., the high culture of Thucydides. And – it has ultimately shown itself to be right: every advance in epistemological and moral knowledge has reinstated the Sophists – Our contemporary way of thinking is to a great extent Heraclitean, Democritean, and Protagorean: it suffices to say it is Protagorean, because Protagoras represented a synthesis of Heraclitus and Democritus.” Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 2.428 Reappraisals of the authorship & dating of the Prometheia trilogy • Traditionally thought to have been composed by Aeschylus (c.525-c.456 BCE). • More recent scholarship has demonstrated the play to have been written by a later, lesser author sometime in the 430s. • This new dating raises many questions as to what contemporary events the trilogy may be referring. -

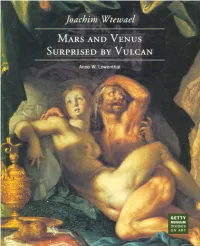

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

Cronus, and the Other Know…? Titans to Become the King of the Gods

Mount Olympus The ancient Greeks believed in many There were some very powerful different gods and goddesses. The most gods who did not actually live powerful 12 lived on the top of Mount on Mount Olympus, such as Olympus. This is where meetings were Hades, god of the underworld. held and arguments were settled. Zeus Zeus was the most powerful of all the gods. He was god of the sky and the King of Mount Olympus. He was married to the queen of the gods, Hera. His temper affected the weather, and when he was angry he threw thunderbolts. Did You Zeus defeated his father, Cronus, and the other Know…? Titans to become the King of the Gods. Poseidon Poseidon was the god of the sea. He was the most powerful god except for his brother, Zeus. He lived in a beautiful palace under the sea and caused earthquakes when he was angry. Sailors would pray to Poseidon for safe passage across the seas before a voyage. Did You He rode a chariot pulled by seahorses. Know…? Hades Hades was the brother of Zeus and the god of the dead. He ruled the underworld, where people went when they died. Hades had a helmet that could make him invisible. Hades had a three-headed dog called Cerberus which guarded the Underworld. Did You He was also the god of wealth because of the Know…? precious metals mined from the earth. Hestia Hestia was the sister of Zeus. She was the goddess of the hearth and the home. Hestia was deeply honoured by ancient Greek women, who would present their newborn children to hearths to receive her blessing. -

The Limits of Communication Between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns

Body Language: The Limits of Communication between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns. Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bridget Susan Buchholz, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Sarah Iles Johnston Fritz Graf Carolina López-Ruiz Copyright by Bridget Susan Buchholz 2009 Abstract This project explores issues of communication as represented in the Homeric Hymns. Drawing on a cognitive model, which provides certain parameters and expectations for the representations of the gods, in particular, for the physical representations their bodies, I examine the anthropomorphic representation of the gods. I show how the narratives of the Homeric Hymns represent communication as based upon false assumptions between the mortals and immortals about the body. I argue that two methods are used to create and maintain the commonality between mortal bodies and immortal bodies; the allocation of skills among many gods and the transference of displays of power to tools used by the gods. However, despite these techniques, the texts represent communication based upon assumptions about the body as unsuccessful. Next, I analyze the instances in which the assumed body of the god is recognized by mortals, within a narrative. This recognition is not based upon physical attributes, but upon the spoken self identification by the god. Finally, I demonstrate how successful communication occurs, within the text, after the god has been recognized. Successful communication is represented as occurring in the presence of ritual references.