Carlonemfa Thesis.Pdf (10.69Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

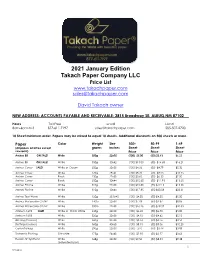

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

A Quest for the Golden Fleece

A Quest for the Golden Fleece Donald Farnsworth Copyright © 2017 Donald Farnsworth, all rights reserved. Any person is hereby authorized to view, copy, print and distribute this document for informational and non-commercial purposes only. Any copy of this document or portion thereof must include this copyright notice. Note that any product or technology described in the document may be the subject of other intellectual property rights reserved by Don- ald Farnsworth and Magnolia Editions or other entities. 2 A Quest for the Golden Fleece Rarely have I encountered an entangled mat of cellulose fibers I didn’t appreciate in one way or another. Whether textured or smooth, pre- cious or disposable, these hardy amalgams of hydrogen-bonded fibers have changed the world many times over. For centuries, human history has been both literally written on the surface of paper and embedded deep within its structure. In folded and bound form, mats of cellulose fibers ushered in the Enlightenment; by enabling multiple iterations and revisions of an idea to span generations, they have facilitated the design of airships and skyscrapers, or the blueprints and calculations that made possible the first human footsteps on the moon. Generally speaking, we continue to recognize paper by a few basic characteristics: it is most often thin, portable, flexible, and readily ac- cepting of ink or inscription. There is, however, a particular sheet that is superlatively impressive, exhibiting an unintentional and unpreten- tious type of beauty. At first glance and in direct light, it may trick you into thinking it is merely ordinary paper; when backlit, the care- ful viewer may detect subtle hints of its historical pedigree via telltale watermarks or chain and laid lines. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

PDF File Generated From

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] - __ , 15b3~... : r . ~ '1'0 'DIE MINIS'.l'RY CF DUEft ;,-"-......#_ ' IP/mfl8()/U)l -· . -

Summer 2017 Summer 2017 Ssa Community Calendar All Events Are FREE and Open to the Public Unless Otherwise Noted

art classes adults • teens • children summer 2017 summer 2017 ssa community calendar All events are FREE and open to the public unless otherwise noted. 44th Annual FIESTA ARTS FAIR | Sat & Sun, Apr 22 & 23 Historic Ursuline Campus | Paid Admission Over 110 regionally and nationally recognized artists are the highlight of this favorite Fiesta event—great music, food, and a Young Artists Garden add to the enjoyment. Proceeds benefit the SSA’s programs. Advance tickets available online at www.swschool.org/FiestaArtsFair. ClOSEd | Battle of Flowers | Fri, Apr 28 SAVOR THE ARTS | Thurs, May 18 | 7:00 – 11:00pm Paid Admission | Santikos Building Join us for the 16th annual friendraiser event to benefit the Young Artist Programs of the SSA! Enjoy a preview of the exhibition, complimentary libations, and culinary creations by some of San Antonio’s finest chefs. Advance tickets available online at www.swschool.org/savorthearts. EXHIBITIONS | May 19 – Jul 16 OPENING RECEPTION | Fri, May 19 | 5:30 – 7:30 pm Victor Pérez-Rul: The Odds Russell Hill Rogers Gallery I Mexican artist Pérez-Rul (Mexico City) exhibits works that detail. kristy Perez. Self-Portrait, 2017, Staedtler pigment liner explore and exploit the relationships between energy, pen on Fabriano paper matter, and consciousness through sculpture, installations, interactivity, sound, and performance. Esteban Delgado: Paintings Russell Hill Rogers Gallery II Referencing the minimalist works of Josef Albers and apr.may.jun.jul.aug Ad Reinhardt, San Antonio artist Delgado exhibits abstract paintings that present a contemporary investigation of REGISTRATION for Summer 2017 Term abstracted enviroments and the landscape, represented Members Priority Online | Tues, Apr 4 | 9:00am through bold shapes and colors. -

The Fundamentals of Papermaking Materials

Preferred citation: D. Radoslavova, J.C. Roux and J. Silvy. Hydrodynamic modelling of the behaviour of the pulp suspensions during beating and its application to optimising the refi ning process. In The Fundametals of Papermaking Materials, Trans. of the XIth Fund. Res. Symp. Cambridge, 1997, (C.F. Baker, ed.), pp 607–639, FRC, Manchester, 2018. DOI: 10.15376/frc.1997.1.607. HYDRODYNAMIC MODELLING OF THE BEHAVIOUR OF THE PULP SUSPENSIONS DURING BEATING AND ITS APPLICATION TO OPTIMISING THE REFINING PROCESS Authors: D Radoslavova, J C Roux, J Silvy* UMR Génie des Procédés Papeties 5518 CNRS EFPG-INPG Domaine Universitaire, BP 65, 461 rue de la Papeterie 38402 Saint-Martin d'Héres, Cedex FRANCE * Presentaddress : Universidade da Beira Interior Rua Marques d'Avila e Bolama 6200 Covilhà PORTUGAL 608 INTRODUCTION The theoretical approach proposed in this research paper aims to relate the energy efficiency coefficient ofthe refiner to the rheological pulp properties . The theory is then used to predict the observed energy consumption as a function of the desired paper properties . Various aspects of the beating process have been previously discussed in review articles [1],[2] and this discussion will not be repeated in this paper. Even in the sixties, the major characteristics of the beating as a dynamic process, were pointed out very clearly. Halme [3], in an interesting survey , mentioned that the pressure in the beating zone must be combined with the relative motion of the surfaces to produce acceptable beating effects on the fibres. It was also clear that the beating effect of the turbulence alone was negligible. -

Evaluation of Conservation Quality Eastern Papers Regarding Materials and Process

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Minah Song Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Minah Song, ‘Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 137–48. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 137 Minah Song Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Introduction When conservators try to find a specific type of Eastern paper for a certain project, they think about visual specifications, permanence and durability, and, of course, about the price. -

Ref. 676.03 SMO 2Nd

INDEX Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter A test 14 acid pretreatment 10 acetate 4 acidproof brick 8 abaca 3 acetate laminating 18 acid pulping 8 abatement 20 acetate pulp 4 acid rain 21 odor 21 acetic acid 4 acid-refined tall oil 6 pollution 20 acetic anhydride 4 acid-resistant 14 abatement device 21 acetone 4 acid size 5 abietic acid 6 acetylated starch 5 acid-stable size 5 abrasion 24 acetyl radical 4 acid sulfite process 8 abrasion debarker I acetylating agent 4 acid tower 8 abrasion resistance 14 acid(s) 4, 8 acid treatment 10 abrasion test 14 abietic 6 acidulating 4 abrasive 7 acetic 4 acidulating agent 4 abrasive backing papers 16 accumulator 8 acidulation 6 abrasiveness 14 carbonic 20 acoustical board 16 abrasive segment 7 Caro's 10 acoustical testing 14 abrasivity (of mineral fillers) 13 cooking 8 acoustic leak detector 9 absorbency 11,14 digester 8 acre-foot 20 relative II fatty 6 acrylamide resins 5 water II formamidine sulfinic 10 acrylic binders 17 absorbent 14,24 formic 4 acrylic fiber 3 absorbent capacity II glucuronic 4 activatable chemical 9 absorbent grades 16 humic 20 activated carbon 20 absorption 5 hydroxy 4 activated sludge 20 capillary 13 hypochlorous 10 activated sludge loading 20 ink 14 lignosulfonic 8 activated sludge process 20 light 14 linoleic 6 activation 4 mechanical 13 mineral 4 surface II tensile energy 14 oleic 6 activation energy 8 vapor 13 pectic 4 Arrhenius 4 absorption coefficient 14 peracetic 10 activator 5 accelerated aging 14 raw 8 active alkali 8 accelerated aging test 14 resin -

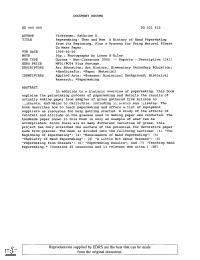

Papermaking: Then and Now. a History of Hand Papermaking from Its Beginning, Plus a Process for Using Natural Fibers to Make Paper

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 440 909 SO 031 615 AUTHOR Vickerman, Kathrine D. TITLE Papermaking: Then and Now. A History of Hand Papermaking from Its Beginning, Plus a Process for Using Natural Fibers To Make Paper. PUB DATE 1995-00-00 NOTE 93p.; Photographs by Lyssa O'Riley. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055)-- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art Education; Art History; Elementary Secondary Education; *Handicrafts; *Paper (Material) IDENTIFIERS Applied Arts; *Grasses; Historical Background; Historical Research; *Papermaking ABSTRACT In addition to a historic overview of papermaking, this book explains the painstaking process of papermaking and details the results of actually making paper from samples of grass gathered from Arizona to ;:ianesota, and Maine to California, including 11 sL.a;:es ana :iimates. The book describes how to teach papermaking and offers a list of equipment suppliers as resources for help getting started. A study of the effects of rainfall and altitude on the grasses used in making paper was conducted. The handmade paper shown in this book is only an example of what can be accomplished. Since there are so many different varieties of grass, this project has only scratched the surface of the potential for decorative paper made from grasses. The book is divided into the following sections: (1) "The Beginning of Papermaking"; (2) "Renaissance of Hand Papermaking"; (3) "Chemistry of Hand Papermaking"; (4) "A Little Bit about Grasses"; (5) "Papermaking from Grasses"; (6) "Papermaking Results"; and (7)"Teaching Hand Papermaking." (Contains 25 resources and 13 relevant Web sites.) (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Cyanotype Process

CHAPTER 7 THE CYANOTYPE PROCESS ! Fig 7-1 here, (Christopher James, Foot of the Pyramid, 1994- toned cyanotype) OVERVIEW & EXPECTATIONS The cyanotype, or Ferro-Prussiate Process, is often the first technique that any of us learn in alternative process photography. Cyanotype is the proverbial “first kiss” that sinks the hook and makes us fall in love with all of the possibilities to come with alternative process image making… in much the same way that the wet lab darkroom experience did to all of the image makers who had the pleasure of that experience. The primary reason for this affection is the absolute simplicity of the process and chemistry, and the nearly fail-safe workflow. This is the process that is ideal for both © Christopher James, The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes: 3rd Edition, 2014 student and teacher alike as the opportunity of making a great print, and experiencing success the first time it is taught or attempted, is very high. As an example, I always begin a class or workshop with a 9’ x 18’ cyanotype mural on pre-sensitized fabric. This bonds a class and facilitates the student’s experience in making a beautiful giant size mural with nothing more than a piece of prepared cotton fabric, sunlight, themselves as the subject, a hose, an ocean, a stream or plastic trash can filled with water, and a dash of hydrogen peroxide for a cheap thrill finish. In the Cyanotype Variations chapter I will give you a step-by-step guide for making this project work as a class or for a family gathering at the beach. -

Eco-Friendly Handmade Paper Making

Booklet on ECO-FRIENDLY HANDMADE PAPER MAKING Shri AMM Murugappa Chettiar Research Centre Taramani, Chennai –600113. December 2010 Booklet on ECO-FRIENDLY HANDMADE PAPER MAKING Shri AMM Murugappa Chettiar Research Centre Taramani, Chennai –600113. December 2010 Title : ECO-FRIENDLY HANDMADE PAPER MAKING Authors : Dr. Hari Muraleedharan, Sr. Programme Officer Dr. K. Perumal, Dy. Director (R&D and Admin.) Shri AMM Murugappa Chettiar Research Centre, Taramani, Chennai 600 113. Email : [email protected] Web : amm-mcrc.org Financial Support : DST-Core support Programme SEED Division - SP/RD/044/2007 Department of Science and Technology (DST) Ministry of Science & Technology, Block-2, 7th Floor C.G.O Complex, Lodi Road, New Delhi- 110 003. Publisher : Shri AMM Murugappa Chettiar Research Centre, Taramani, Chennai 600 113. Email : [email protected] Web : amm-mcrc.org Phone : 044-22430937; Fax: 044-22430369 Printed by : J R Designing, Printing and Advertisement Solutions, Palavakkam, Chennai - 600 041. Ph. +91-9962391748 Email : [email protected] Year of Publishing : December 2010 2 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Significance of eco-friendly paper making 5 3. Handmade paper making for rural development 5 4. Materials Required for Hand Made Paper Production 6 4.1 Mould and deckle 8 5. MCRC’s technology on Hand made Paper Production 10 5.1 Raw material selection 10 5.2 Extraction of Fiber from Plants 10 5.3 Screening of Microoraganisms for Biotreatment 11 5.4 Bio Pulping & Bio-bleaching 12 5.5 Washing 12 5.6 Beating and blending 12 5.7 Placing Hand VAT in the sink 13 5.8 Adding Binding materials 13 5.9 Processing of sizing 13 5.10 Refining 13 6. -

A Guide to Japanese Papermaking

A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd Edition A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd edition ISBN: 978-0-9799164-8-9 © 1989, 1997, 2018 Donald S. Farnsworth English translations © 1948 Charles E. Hamilton MAGNOLIA EDITIONS 2527 Magnolia St, Oakland CA 94607 Published by Magnolia Editions, Inc. www.magnoliapaper.com Table of Contents Author’s Preface 1 (Kunisaki Jihei, 1798; trans. Charles E. Hamilton, 1948) Introduction 3 Equipment (contemporary) 8 Cooking 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bleaching 27 I. Sunlight Bleaching (ultraviolet light) 28 Japanese text by Kunisaki Jihei and woodcut illustrations by Seich- II. Hydrogen Peroxide Bleaching 29 uan Tōkei are reproduced from a 1925 edition of Kamisuki chōhōki III. Chlorine Bleaching 30 (A Handy Guide to Papermaking), first published in 1798. Beating 31 Charles E. Hamilton's translations are reproduced from the 1948 Pigmenting 37 English language edition of A Handy Guide to Papermaking pub- Dyeing 39 lished by the Book Arts Club, University of California, Berkeley. Formation Aid 45 With the 1948 edition now out of print and increasingly difficult Mixing Formation aid powder PMP 46 to find, I hope to honor Mr. Hamilton's efforts by bringing his thoughtful and savvy translations to a broader audience. His trans- Contemporary vat, wooden stirring comb... 48 lations appear italicized and circumscribed in the following text. Sheet Formation 51 I. Japanese: Su and Keta 54 I would like to acknowledge Mr. Fujimori-san of Awagami Paper II. Pouring Method 59 and his employees, Mr. Yoshida-san and his employees, for fur- thering my understanding of Japanese papermaking.