“But I Will Tell of Their Deeds”: Retelling a Hasidic Tale About the Power of Storytelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreword by Rabbi Zev Leff

THIS TOO IS FOR THE BEST THIS TOO IS FOR THE BEST Approaching Trials and Tribulations from a Torah Perspective RABBI YERACHMIEL MOSKOFF לזכרון עולם בהיכל ה' נשמת אדוני אבי רבי נח משה בן רבי יצחק אלחנן הכהן זצ"ל - מלץ .Mosaica Press, Inc © 2013 by Mosaica Press נאמן בדרכיו ומעשיו Edited by Doron Kornbluth Typeset and designed by Rayzel Broyde נוח לשמים ונוח לבריות All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-937-88705-6 ISBN-10: 1-937-88705-7 ותמיד צהלתו על פניו ,No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from both the copyright השפיע במדות אלו לכל מי שהכירו .holder and the publisher יהי זכרו ברוך :Published and distributed by Mosaica Press, Inc. נלב"ע ט"ז שבט תשס"ב www.mosaicapress.com [email protected] הונצח ע"י בנו הלל שליט"א Printed in Israel ויה"ר שיזכה להגדיל תורה ולהאדירה מתוך הרחבת הדעת ומנוחת הנפש תנצב"ה In Loving Memory of Mordechai and Dutzi Mezei I wish to dedicate my first English sefer to ,my dear parents לעילוי נשמת מרדכי בן משה צבי הלוי דבורה בת אליעזר הכהן Devorah bas Eliezer (HaKohen) was a true Akeres Habayis. She loved Franklin and Sheila her children and grandchildren with all her heart. The beautiful homes and families that her children and grandchildren have built is a testament to the incredible woman that she was. Moskoff Mordechai ben Moshe Tzvi (HaLevi) was truly an Ish Gam Zu L’Tova. -

FEDERATION PROGRAMS Teachers Reflect on Their P2G Experience Four Chattanooga Teachers Recently Traveled to Israel As Part of the P2G (Partnership Together) Program

FEDERATION PROGRAMS Teachers Reflect on their P2G Experience Four Chattanooga teachers recently traveled to Israel as part of the P2G (Partnership Together) program. Here are their summaries of their experiences. Riki Jordan Odineal: As an educator, there is nothing better than experiencing the education system of another area or country. When I went on the P2G Educator's Delegation over winter break, I knew I was in for a special trip. I was not disappointed! I spent two days at Mevoot Eron High School in Hadera in history, geography, art, and science classrooms. This is the kibbutz school for the four kibbutzim in the area. The students were engaged and curious. They also enjoyed the pencils, Little Debbies, and homemade tzedekeh box (made by my Sunday school class) I brought with me. I also had the opportunity to stay on a kibbutz with my new Israeli family. I stayed on Kibbutz Barkai, which is 15 minutes northeast of Hadera. There are no words for the warmth and hospitality I received from everyone on the kibbutz. I've never had more fresh produce in my life! I was definitely a fan of kib- butz life. Most importantly, I made many connections in both our Southeastern Region in the U.S. and our partnership region in Israel. It was amazing networking with our Israeli counterparts and planning future activities between our schools. We've also made plans to socialize with our Nashville and Knoxville coun- terparts. This trip was life-changing, and I am so thankful to the Federation for the opportunity! SE P2G group in the Cardo section of Old Jerusalem Rebecca Sadowitz: I want to thank the Federation so much for sending me to Israel for the educator’s consortium, Partnership Together. -

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Chabad of Northern Beverly Hills Rabbi Yosef Shusterman

B"H Chabad of Northern Beverly Hills, 409 Foothill Road . Beverly Hills, CA 90210 Rabbi Yosef Shusterman 310/271-9063 MAY 5, 2000 VOL 3, ISSUE 30 30 NISSAN 5760 PARSHAT KEDOSHIM fear our parents does not derive from our dependence on them. Even as adults with our own households, we must still fear our parents simply In the beginning of this week's Torah portion, Kedoshim, we find three because of who they are. commandments: 1) "You shall be holy," 2) "Every man shall fear his mother and father," 3) "My Sabbaths you shall keep." As these three mitzvot appear "You shall love your fellow..." (19:18) QUESTION: What is the together, it follows that a connection exists between them. ultimate ahavat Yisrael? ANSWER: The famous Chassidic Rabbi, Reb The first commandment in the sequence is "You shall be holy." A Jew Moshe Leib of Sassov once said that he learned the meaning of ahavat must be holy, distinct from other nations, for the Jewish people is unique. Yisrael from a conversation he overheard between two simple farmers. And yet, the holiness of the Jew, that which makes him different from the While sitting in an inn and drinking, they became a little drunk, and one said gentile, is not expressed in his observance of the commandments. A non- to the other, "Do you really love me?" To which the other replied, "Of Jew is not obligated to keep the Torah's mitzvot; he has no common ground course I love you." The first one asked again, "If you really love me, tell me or connection with them. -

Hasidic Tales-Text-REV

Introduction When faced with a particularly weighty problem, the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidic Judaism, would go to a certain place in the woods, light a sacred fire, and pray. In this way, he found insight into his dilemma. His successor, Rabbi Dov Ber, the Preacher of Mezritch, followed his example and went to the same place in the woods and said, “The fire we can no longer light, but we can still say the prayer.” And he, too, found what he needed. Another generation passed, and Rabbi Moshe Leib of Sassov went to the woods and said, “The fire we can no longer light, the prayer we no longer remember; all we know is the place in the woods, and that will have to suffice.” And it did. In the fourth generation, Rabbi Israel of Rishin stayed at home and said, “The fire we can no longer light, the prayer we no longer know, nor do we remember the place. All we can do is tell the tale.” And that, too, proved sufficient. But why? Why is it that telling the story carries the same healing power as the original act? Because the story recreates the act in such a way as to invite us into it. We don’t simply listen to a story; we become the story. The very act of giving our attention to the story gives the story a personal immediacy that erases the boundary between the story and ourselves. Although the power of the story to engage the listener is not unique to Jews, it is explicit in Judaism. -

Parshat Mishpatim 5773

Written by: David Prins Editor: David Michaels Parshat Emor 5777 as much as from what their Rabbi said. They too did not speak respectfully to each other, especially when they had differing political views among themselves. We see from here the Rabbi Akiva’s students- We are in the period of the Omer between Pesach and Shavuot, and awesome responsibility of a Rebbe. We also see what eventuates when people supposedly on the command to count the Omer is in this week’s Parasha. Rabbi Akiva had 12,000 pairs of the same side deflect their energy away from the enemy and towards their own internal students. They all died in the Omer period because they did not treat each other with respect dissensions. This is the causeless hatred which has always caused Israel to miss its chance for (Yevamot 62b). Rabbi Nachman adds that the physical cause of their death was askera, which redemption. Rashi defines as a plague of diphtheria. In his Peninei Halakha, Rav Eliezer Melamed, Rosh Yeshivat Har Bracha, suggests an alternative Rav Sherira Gaon wrote in his Iggeret that they died as a result of shemada, which would suggest explanation that aligns with Rashi’s explanation of askera. Some of Rabbi Akiva’s students joined that their deaths had to do with the use of force and Roman persecution. Etz Yosef comments the Bar Kochba rebellion while others continued in their studies. The two camps behaved on Bereishit Rabba 61:3 that they died in the battle of Betar. The Etz Yosef comments similarly on contemptuously toward each other. -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

The Chabad Weekly

B”H The Chabad Weekly Parshas Vayikra Chabad of Beverly Hills Vol. 24 Issue 23 6 Nissan, 5781 / March 19, 2021 9145 Wilshire Blvd. Beverly Hills, CA 90210 Candlelighting his own personal set of clothing to Chabadofbeverlyhills.com (Los Angeles) Identity Crisis distinguish him from others, he might Rabbi Yosef Shusterman 6:46 PM By Rabbi Yossi Goldman suffer an identity crisis. So he devised Rabbi Mendel Shusterman Amnesia is a frightening illness. Imag- a plan. He tied a red string around his 310-271-9063 big toe so that even in the bathhouse Friday Mincha: ine forgetting who you are — sudden- ly you have no family, no history, and he would stand out from everyone else. Sadly, when he was in the shower, 7:00 PM no identity. It can happen to an indi- In Place of a Temple Offering vidual and it can happen to a people. the water and soapsuds loosened the There have been times in our history red string, and it slipped off his big toe. LATEST SHEMA: 10:00 when we seemed to forget who we To make matters worse, the red string Rabbi Moshe-Leib of Sassov once were and where we came from. And floated along to the next cubicle and came to the marketplace in Yaro- all too often, we seem uncertain twirled around the big toe of the fellow SHABBAT SCHEDULE under the next shower. slav. He was passing among the about where we are going. vendors, checking the quality of the Suddenly, our Chelmer genius discov- Shacharis 7:30 AM In the opening chapters of Leviticus, straw and hay for sale, when he 9:30 AM we read the expression Nefesh ki ered that his string was gone. -

Chabad Chodesh Shevat 5776– Shnas Hakhel

בס“ד Shevat 5776/2016 SPECIAL DAYS IN SHEVAT Volume 26 Issue 11 Shevat 1/January 11/Monday Rosh Chodesh Shevat Plague of locusts started. Moshe Rabbeinu began the review of the Torah, the Mishneh Torah, for thir- ty-six days, until his death, (Devarim 1:3) [2488]. Jews expelled from Genoa, Italy, 5358 [1598]. Yartzeit of R. Moshe Shick, “the MaHa- RaM Shick”, Talmudist, 5639 [1859]. Shnas Hakhel Shnas Shevat 2/January 12/Tuesday went home and she announced that Yanai Death of King Alexander Yanai, oppo- died. They made that day a holiday” – nent of the Chachamim, 3690 [76 (Megilas Taanis). BCE]. “...Yanai arrested seventy Elders of Yartzeit of R. Meshulam Zusia of Annipoli, Israel and told the jail keeper, “If I die, author of Menoras Zahav, student of the kill these Sages so that if Israel rejoices Mezeritcher Magid, 5660 [1800]. He was over me, they will mourn over their one of two people chosen by the Alter Reb- Teachers”... His righteous wife Shala- be to write a Haskamah to the Tanya; in min took off his signet ring when he fact the Alter Rebbe agreed to print the died and sent it to the jail keeper and Tanya, only on condition that it be with R. said, “Your master released them.” They Yud Shevat Tuesday Night - Wednesday / Jan. 19-Jan.20 TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCK PARK “...In reply to the many questions about a the Maftir should be the most respected detailed schedule for the Tenth of Shevat, member of the congregation, as deter- the Yartzeit of my revered father-in-law, mined by the majority of the congregation; the Rebbe, I suggest the following: alternatively, the choice should be deter- mined by lot. -

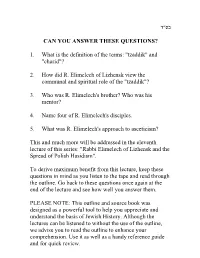

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. What Is the Definition of the Terms: "Tzaddik" and "Chasid"? 2. How Did R

c"qa CAN YOU ANSWER THESE QUESTIONS? 1. What is the definition of the terms: "tzaddik" and "chasid"? 2. How did R. Elimelech of Lizhensk view the communal and spiritual role of the "tzaddik"? 3. Who was R. Elimelech's brother? Who was his mentor? 4. Name four of R. Elimelech's disciples. 5. What was R. Elimelech's approach to asceticism? This and much more will be addressed in the eleventh lecture of this series: "Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk and the Spread of Polish Hasidism". To derive maximum benefit from this lecture, keep these questions in mind as you listen to the tape and read through the outline. Go back to these questions once again at the end of the lecture and see how well you answer them. PLEASE NOTE: This outline and source book was designed as a powerful tool to help you appreciate and understand the basis of Jewish History. Although the lectures can be listened to without the use of the outline, we advise you to read the outline to enhance your comprehension. Use it as well as a handy reference guide and for quick review. THE EPIC OF THE ETERNAL PEOPLE Presented by Rabbi Shmuel Irons Series X. Lecture #11 RABBI ELIMELECH OF LIZHENSK AND THE SPREAD OF POLISH HASIDISM I. R. Elimelech of Lizhensk and His Profound Influence A. lceb oiadl dfa 'itd .dpcer miig md xy` miigd on ezn xaky miznd z` ip` gaye dxdp rtez mdilr mdixg` mi`ad zexec xecl mzyecw mver mikiynnd miwicvd zelrn dpifgz epipir xy`k c"ecl mdicinlz icinlze mdicinlzl eyixed xy` dyecwd xe`n dpy mipeny aexw df xy` d"dlf jlnil` x"xden yecwd axd zelrn lcebn mixyin wqet epi`y xdpk eicinlz icinlz xec xecl yecwd exe` rtez meid cre enlerl jldy mihewil - wqn`cxn dnly 'xn dxezd lr dnly zx`tz 'q .r"if xdhl `ay in lkl ek:a zldw "I praise the dead, who have already passed away, more than the living, who still are alive." (Ecc. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending