INR 432 COURSE TITLE: Afro-Asian Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the John Gunther Papers 1935-1967

University of Chicago Library Guide to the John Gunther Papers 1935-1967 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 9 Information on Use 9 Access 9 Citation 9 Biographical Note 9 Scope Note 10 Related Resources 12 Subject Headings 12 INVENTORY 13 Series I: Inside Europe 13 Subseries 1: Original Manuscript 14 Subseries 2: First Revision (Second Draft) 16 Subseries 3: Galley Proofs 18 Subseries 4: Revised Edition (October 1936) 18 Subseries 5: New 1938 Edition (November 1937) 18 Subseries 6: Peace Edition (October 1938) 19 Subseries 7: 1940 War Edition 19 Subseries 8: Published Articles by Gunther 21 Subseries 9: Memoranda 22 Subseries 10: Correspondence 22 Subseries 11: Research Notes-Abyssinian War 22 Subseries 12: Research Notes-Armaments 22 Subseries 13: Research Notes-Austria 23 Subseries 14: Research Notes-Balkans 23 Subseries 15: Research Notes-Czechoslovakia 23 Subseries 16: Research Notes-France 23 Subseries 17: Research Notes-Germany 23 Subseries 18: Research Notes-Great Britain 24 Subseries 19: Research Notes-Hungary 25 Subseries 20: Research Notes-Italy 25 Subseries 21: Research Notes-League of Nations 25 Subseries 22: Research Notes-Poland 25 Subseries 23: Research Notes-Turkey 25 Subseries 24: Research Notes-U.S.S.R. 25 Subseries 25: Miscellaneous Materials by Others 26 Series II: Inside Asia 26 Subseries 1: Original Manuscript 27 Subseries 2: Printer's Copy 29 Subseries 3: 1942 War Edition 31 Subseries 4: Printer's Copy of 1942 War Edition 33 Subseries 5: Material by Others 33 Subseries 6: -

ILS Yearbook 2020 (PART 1)

To develop 21st Century learners in a stimulating, caring and vibrant environment and empower them to achieve their personal and professional goals. 1. To Introduce Student Centered Learning 2. To Blend in Benchmark Assessment 3. To Inculcate Employability Skills 4. To Nurture Core Values INDIAN LANGUAGE SCHOOL 2019 - 2020 Innovation in Education Education is the base of every society. It is often said that what and how we learn in school determines who we become as individuals in life. Education determines our ability to communicate, solve problems, our interpersonal relationships and how we perceive the world around us. With the blending of technology in every walk of life there is a dire need for innovation in education to meet the challenges of the fast-changing and unpredictable globalized world. There is still a significant gap between the potential of modern education and what students actually learn at school. Many educators still practice rote and old ineffective methods of teaching and learning. The adoption and exploration of innovative ideas in education is often slow and the acceptability to the change is very low. Since the delivery by teacher and expectations of students is mismatched most of the students have short attention span during class, feel unengaged and resort to in disciplinary activities in classrooms. Integrating Art in learning gives diverse opportunities to learners and makes learning interesting ,engaging, faster and efficient. Facilitating learning based on different learning styles is yet another way to engage learners. Technology allows teachers to individualize lesson plans to different students and their unique styles of learning. -

September 2016 (Current Affairs for 2017)

INDEX September 2016 (Current Affairs for 2017) 1. SOCIAL ISSUES 6-19 1.1 National Policy Of Women, 2016 1.2 National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme 3 1.3 Leprosy Case Detection Campaign (LCDC) 1.4 Higher Education Financing Agency 1.5 The Civil Aspects Of International Child Abduction Bill, 2016 1.6 BRICS Conference on Negation of Drug Abuses 1.7 Mission Parivar Vikas 1.8 Maratha Reservation Protest 1.9 Swachh Survekshan Gramin 2016 1.10 Lancet Report on Maternal Health 2. POLITY AND GOVERNANCE 20-34 2.1 Advancing The Budget 2.2 Merger of Plan and Non-Plan classification in Budget and Accounts 2.3 Triple Talaq and Need for Judicial Intervention 2.4 Introducing Totaliser Machine In election 2.5 Municipal Bonds in India 2.6 The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016 2.7 Fresh Guidelines for Flexi-Fund for Centrally Sponsored Scheme 2.8 Schemes Need Prior Approval of Finance Ministry 2.9 NITI Ayoga’s Plan for 50 Medals in 2024 Olympics 2.10 National Party Status to Trinamool Congress Current Affairs For 2017- (September 2016) Page 1 3. ECONOMY AND INFRASTRUCTURE 35-48 3.1 Flexi Fare Method of Railway 3.2 New Guidelines to Regulate Indian Direct Selling Industry 3.3 Appointment of Part-time Chairman of UIDAI 3.4 Excess Capacity Issue In Steel Industry 3.5 World Manufacturing Production Report 3.6 Controversy Surrounding Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) 3.7 Stressed Loans 3.8 Micro Finance Sector 3.9 Buffer Stocks Limits Of Pulses Increased 3.10 e-Nivaran 3.11 NIIF to Manage $2-bn Green Energy Fund 3.12 Andhra Becomes Second State To Achieve 100% Access To Electricity 4. -

Investor Pack for Q1 FY 14

Quarterly Earning Release First Quarter FY 14 November 15, 2013 HCL Infosystems Ltd Table of Contents CEO’s Comments 2 Business Highlights 3 Standalone Results 5 Consolidated Results 7 CEO’s COMMENTS Mr. Harsh Chitale, Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director, HCL Infosystems Limited, commenting on the results said, “Our Scheme of Arrangement on Restructuring has become effective from 1st Nov 2013. Under the restructured organization, the Company’s businesses of Solutions, Services and Learning stand transferred to the wholly-owned subsidiaries - HCL Infotech Ltd., HCL Services Ltd, and HCL Learning Ltd. respectively. The restructuring would now enable us to have undivided focus and attention on our key growth engines – Distribution and Services business. Our Distribution business witnessed a Q-o-Q growth of 13% backed by robust growth of our Telecom Distribution revenues. Continued growth of our Telecom Distribution since last two quarters is a 2 testimony that the revamped product portfolio of our Principal is now gaining positive traction in the market. At the same time, our momentum of diversifying our product portfolio to non-Telecom products continued with signing up of many leading brands such as HP, Microsoft, Delta, Lenovo, Karbonn Tablets, Lava Tablets, etc. in this quarter. Our Services business has built a healthy order book on back of large Managed Services deals, Application Services growth in Middle East and Break-fix services outsourcing deals. Our Managed Services business continued robust growth in Singapore as well with a major win from a large Public Board in Singapore. The Services business saw a Y-o-Y growth of nearly 15% in this quarter. -

Rights Issue Circular

THIS RIGHTS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND SHOULD BE READ CAREFULLY. If you are in any doubt about its contents or the action to be taken, please consult your Banker, Stockbroker, Accountant, Solicitor or any other Professional Adviser for guidance immediately. Investors are advised to note that liability for false or misleading statements made in connection with the Right Circular are provided in sections 85 and 86 of the Investment and Securities Act No. 29, 2007 (“the Act”). For information concerning certain risk factors which should be considered by shareholders, see “Risk Factors” on page 61- 62 of this Rights Circular RC: 6753 RIGHTS ISSUE OF 13,635,796,006 ORDINARY SHARES OF N0.50 EACH AT N0.50 PER SHARE ON THE BASIS OF THIRTY-EIGHT (38) NEW ORDINARY SHARES FOR EVERY FIFTEEN (15) ORDINARY SHARES HELD AS AT THE CLOSE OF BUSINESS ON JANUARY 31, 2020 PAYABLE IN FULL ON ACCEPTANCE ACCEPTANCE LIST OPENS: AUGUST 10, 2020 ACCEPTANCE LIST CLOSES: SEPTEMBER 17, 2020 THE RIGHTS BEING OFFERED ARE TRADABLE ON THE FLOOR OF THE NIGERIAN STOCK EXCHANGE FOR THE DURATION OF THE RIGHTS ISSUE ISSUING HOUSE: ECZELLON CAPITAL LIMITED Rc: 978786 This Right Circular and the securities which it offers, have been cleared and registered by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The Investment and Securities Act provides for civil and criminal liabilities for the issue of a Rights Circular which contains false or misleading information. The clearance and registration of this Rights Circular and the securities which it offers do not relieve the parties of any liability arising under the Act for false and misleading statements or for any omission of a material fact in this Right Circular. -

JOURNAL of LANGUAGE and LINGUISTICS (JOLL) No. 5 April, 2019 NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA FACULTY of ARTS DEPARTMENT of MODER

Journal of Language and Linguistics. No. 5. April, 2019. www.jolledu.com.ng JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS (JOLL) No. 5 April, 2019 NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF MODERN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES i Journal of Language and Linguistics. No. 5. April, 2019. www.jolledu.com.ng Journal of Languages and Linguistics (JOLL) Faculty of Arts Department of Modern European Languages Nnamdi Azikiwe University P.M.B. 5025 Awka, Nigeria All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the editors, who are the copyright owners. ISSN: 2408-7696 E-ISSN : 2659-0689 ii Journal of Language and Linguistics. No. 5. April, 2019. www.jolledu.com.ng THE JOURNAL Journal of Language and Linguistics is a referred journal published by the Editorial Board, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Faculty of Arts, Department of Modern European Languages, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. All views on conclusions contained in the journal are those of the authors of the articles. The opinions expressed are not in any sense, whatsoever, those of the Editorial board of this Journal. JOLL prioritises dissemination of original research works of academics in Nigeria and international tertiary institutions. The Editorial Board hopes that the journal will serve as an effective medium for rapid communication among researches on language and linguistics, in Nigeria and beyond. We are immensely grateful to our editorial consultants and evaluators whose meticulous assessment; approval of manuscripts has actualized this publication. -

Nigeria Bilateral Relations

BRIEF ON INDIA-NIGERIA BILATERAL RELATIONS Overall Relations: India and Nigeria enjoy warm, friendly and deep-rooted bilateral relations. India, with a population of 1.3 billion, and Nigeria, over 190 million, are large developing and democratic countries with multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual societies. India as the largest democracy in the world and Nigeria as the largest in Africa, become natural partners. The struggle against colonialism and apartheid in the formative years after independence of the two countries laid strong foundation for the engagement of the two countries. India and Nigeria are playing an important role in the South-South Cooperation. In the multilateral organisations particularly United Nations, G77 and NAM, both countries have been articulating the voice of the developing world in a coordinated and effective manner. India established its Diplomatic House in Lagos in November 1958, two years before Nigeria became independent in 1960. Political contacts at the highest level were maintained during the last 60 years. The presence of a large Indian expatriate community of about 50,000, the largest in West Africa adds value to the importance of the long-standing relationship between the two countries. Bilateral Visits India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s landmark visit to Nigeria in September 1962 and his interaction with Nigeria’s first Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa had created mutual goodwill, respect and friendship between the two countries and leaders. Two Nigerian Presidents visited India as the Chief Guests at India’s Republic Day i.e. in 1983 by President Shehu Shagari and in 2000 at India’s 50th Republic Day celebrations by President Olusegun Obasanjo. -

Folklife Annual, 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 961 SO 020 180 AUTHOR Jabbour, Alan, Ed.; Hardin, James, Ed. TITLE Folklife Annual, 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0575-2 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 161p.; For the 1986 edition, see SO 020 179. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indians; *Artists; Black Culture; *Canada Natives; Cultural Education; *Folk Culture; *Grief; *Korean Americans; Painting (Visual Arts) IDENTIFIERS Folklorists; *Folktales; German Americans; Hupa (Tribe); Native Americans; Russian Americans ABSTRACT This annual publication is intended to promote the documentation and study of the folklife of the United States, to share the traditions, values, and activities of U.S. folk culture, and to serve as a national forum for the discussion of ideas and issues in folklore and folklife. The articles in this collection are: (1) "Eating in the Belly of the Elephant" (R. D. Abrahams), which delves into the differences between Afro-American folktales and European fairy tales;(2) "The Beau Geste: Shaping Private Rituals of Grief" (E. Brady); (3) "George Catlin and Karl Bodmer: Artists among the American Indians" (J. Gilreath); (4) "American Indian Powwow" (V. Brown and B. Toelken); (5) "Celebration: Native Events in Eastern Canada" (4. S. Cronk, et al.);(6) "Reverend C. L. Franklin: Black American Poet-Preacher" (J. T. Titon); (7) "John Henry Faulk: An Interview" (J. McNutt); (8) "The First Korean School of Silver Spring, Maryland" (L. -

Pascal 2018 Results

The CENTRE for EDUCATION in MATHEMATICS and COMPUTING Le CENTRE d'EDUCATION´ en MATHEMATIQUES´ et en INFORMATIQUE www.cemc.uwaterloo.ca 2018 2018 Results R´esultats Pascal Contest Concours Pascal (Grade 9) (9e ann´ee{ Sec. III) Cayley Contest Concours Cayley (Grade 10) (10e ann´ee{ Sec. IV) Fermat Contest Concours Fermat (Grade 11) (11e ann´ee{ Sec. V) c 2018 Centre for Education in Mathematics and Computing Competition Organization Organisation du Concours Centre for Education in Mathematics and Computing Faculty and Staff / Personnel du Concours canadien de math´ematiques Ed Anderson Angie Hildebrand Jeff Anderson Carrie Knoll Terry Bae Judith Koeller Jacquelene Bailey Laura Kreuzer Grace Bauman Bev Marshman Shane Bauman Mike Miniou Ersal Cahit Dean Murray Serge D'Alessio Jen Nelson Rich Dlin J.P. Pretti Jennifer Doucet Kim Schnarr Fiona Dunbar Carolyn Sedore Mike Eden Kevin Shonk Barry Ferguson Ashley Sorensen Judy Fox Ian VanderBurgh Steve Furino Troy Vasiga John Galbraith Christine Vender Robert Garbary Heather Vo Rob Gleeson Jessica Won Sandy Graham Tim Zhou Conrad Hewitt 2 Competition Organization Organisation du Concours Problems Committees / Comit´esdes probl`emes Pascal Contest / Concours Pascal Aaron Warner (Chair / pr´esidente), St. Mildred's-Lightbourn School, Oakville, ON Janet Christ, Walter Murray C.I., Saskatoon, SK Hwie Lie Johns, Sutherland S.S., North Vancouver, BC Mike Miniou, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON Peter O'Hara, London, ON J.P. Pretti, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON Paule Rodrigue, Franco-Cit´e,Ottawa, ON Jim Schurter, Listowel, ON Anna Spanik, Halifax, NS Cayley Contest / Concours Cayley Jen Nelson (Chair / pr´esidente), University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON Rich Dlin, TanenbaumCHAT Kimel Family Education Centre, Vaughan, ON Barry Ferguson, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON Jordan Grant, St. -

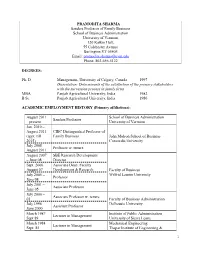

Pramodita Sharma

PRAMODITA SHARMA Sanders Professor of Family Business School of Business Administration University of Vermont 320 Kalkin Hall, 55 Colchester Avenue Burlington VT 05405 Email: [email protected] Phone: 802-656-5122 DEGREES: Ph. D Management, University of Calgary, Canada 1997 Dissertation: Determinants of the satisfaction of the primary stakeholders with the succession process in family firms MBA Panjab Agricultural University, India 1982 B Sc. Panjab Agricultural University, India 1980 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT HISTORY (Primary affiliations): August 2011 School of Business Administration Sanders Professor – present University of Vermont Jan. 2010 – August 2011 CIBC Distinguished Professor of (appt. till Family Business John Molson School of Business 2015) Concordia University July 2008 – Professor w. tenure August 2011 August 2007 SBE Research Development – June 08 Director Sept. 2006 – Associate Dean: Faculty August 07 Development & Research Faculty of Business July 2005 – Wilfrid Laurier University Professor June 08 July 2001 – Associate Professor June 05 July 2000 – Associate Professor w. tenure 01 Faculty of Business Administration July 1996 – Dalhousie University Assistant Professor June 2000 March 1987 – Institute of Public Administration Lecturer in Management Sept 89 University of Sierra Leone March 1984 – Mechanical Engineering Lecturer in Management Sept. 85 Thapar Institute of Engineering & 1 Technology March 1982 – College of Commerce Lecturer in Commerce Feb. 84 Punjabi University ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT HISTORY (Secondary affiliations): -

Awards Committees Country School Name

AWARDS COMMITTEES COUNTRY SCHOOL NAME DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE CAMBODIA ST GEORGE'S COLLEGE DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE KOREA, DEMOCRATIC AYUSH DAVE CONGO, THE DEMOCRATIC FAHAHEEL AL WATANIEH INDIAN PRIVATE SCHOOL DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE REPUBLIC OF THE (DPS KUWAIT) DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE NORWAY EDUSENSEI DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE ARMENIA MODERN SCHOOL, KOTA (RAJASTHAN) HONOURABLE MENTION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE RUSSIA SUPERIOR HIGH SCHOOL HONOURABLE MENTION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE CHINA SANSKRITI SCHOOL HONOURABLE MENTION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE QATAR FOUNTAINHEAD SCHOOL HONOURABLE MENTION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CAMPION SCHOOL HONOURABLE MENTION THE LEGAL COMMITTEE INDONESIA SHAH WASIF FABIAN OUTSTANDING DELEGATE THE LEGAL COMMITTEE FRANCE RAJAGIRI PUBLIC SCHOOL OUTSTANDING DELEGATE THE LEGAL COMMITTEE SPAIN THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BANGALORE OUTSTANDING DELEGATE THE LEGAL COMMITTEE CYPRUS AMITY INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL AMITY INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL SECTOR 46 BEST DELEGATE THE LEGAL COMMITTEE PALAU GURGAON DISARMAMENT & INTERNATIONAL DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION GUATEMALA HIRANANDANI UPSCALE SCHOOL SECURITY COMMITTEE DISARMAMENT & INTERNATIONAL DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION SWEDEN RAJAGIRI PUBLIC SCHOOL SECURITY COMMITTEE DISARMAMENT & INTERNATIONAL KOREA, DEMOCRATIC DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION MERIDIAN SCHOOL, BANJARA HILLS SECURITY COMMITTEE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF DISARMAMENT & INTERNATIONAL DIPLOMATIC COMMENDATION SOUTH KOREA AKSHAR ABROL INTERNATIONAL -

Icai Commerce Quiz 2020

ICAIICAI CCOMMERCEOMMERCE QUIZQUIZ 20202020 The Institute of Chartered Heartiest congratulations from Accountants of India The Career Counselling (Setup by an act of Parliament) Directorate of the ICAI to the below mentioned candidates. CLASS 9 Top 3 Ranks will be given Rs. 10,000 Cash Award each S. Rank Student Login Father's School City State Score No Comments Name Name Name 1 Rank 1 Harsh Gupta 44735 Lokesh Kumar Gupta St. Xavier's School, BHEL, Bhopal Bhopal Madhya Pradesh 86 2 Rank 2 Kalpna Chhabra 32973 Pankaj Chhabra DPS Gurgaon sec 45 Gurgaon Haryana 86 3 Rank 3 Yashvee Gupta 54004 Manoj Gupta G.D.Goenka Public School, Rohini, Sec-22 New Delhi Delhi 85 Next 25 Students will be given Rs. 2000 Cash Award each S. Rank Student Login Father's School City State Score No Comments Name Name Name 4 Next 25 Shivam Rajan Keer 45221 Rajan Sudam Keer Phatak Highschool, Ratnagiri. Ratnagiri Maharashtra 83 5 Next 25 Sai Sri Vyshnavi Para 38547 Seshagiri Para The Indian High School, Dubai Dubai Dubai 83 6 Next 25 Ansh Singhal 46292 Sangeeta Singhal DLDAV Model School Shalimar Bagh New Delhi Delhi 82 7 Next 25 Akshat Jain 45025 Jivandhar Kumar Jain Shri Digambar jain Sanmati Sagar School Toda Raisingh Rajasthan 82 8 Next 25 Tashvi Gupta 35381 Rajat Gupta Delhi Public School Delhi Delhi 80 9 Next 25 Sanskar ranjan 13335 Priyaranjan Seth anandram Jaipuria school Ghaziabad Uttar Pradesh 80 10 Next 25 Maulik 24629 Neeraj Garg Chinar Public School Alwar Rajasthan 80 11 Next 25 Amber Agarwal 41025 Abhinav Agarwal PMS Public School Moradabad Uttar Pradesh 79 12 Next 25 Mansi Dhankhar 42333 Mr.