SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Archeological Survey on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report No. 70

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 70 1968 FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Technical Reports FRE Technical Reports are research documents that are of sufficient importance to be preserved, but which for some reason are not aopropriate for scientific pUblication. No restriction is 91aced on subject matter and the series should reflect the broad research interests of FRB. These Reports can be cited in pUblications, but care should be taken to indicate their manuscript status. Some of the material in these Reports will eventually aopear in scientific pUblication. Inquiries concerning any particular Report should be directed to the issuing FRS establishment which is indicated on the title page. FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD DF CANADA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 70 Some Oceanographic Features of the Waters of the Central British Columbia Coast by A.J. Dodimead and R.H. Herlinveaux FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Biological Station, Nanaimo, B. C. Paci fie Oceanographic Group July 1%6 OONInlTS Page I. INTHOOOCTION II. OCEANOGRAPHIC PlDGRAM, pooa;OORES AND FACILITIES I. Program and procedures, 1963 2. Program and procedures, 1964 2 3. Program and procedures, 1965 3 4 III. GENERAL CHARACICRISTICS OF THE REGION I. Physical characteristics (a) Burke Channel 4 (b) Dean Channel 4 (e) Fi sher Channel and Fitz Hugh Sound 5 2. Climatological features 5 (aJ PrectpitaUon 5 (b) Air temperature 5 (e) Winds 6 (d) Runoff 6 3. Tides 6 4. Oceanographic characteristics 7 7 (a) Burke and Labouchere Channels (i) Upper regime 8 8 (a) Salinity and temperature 8 (b) OJrrents 11 North Bentinck Arm 12 Junction of North and South Bentinck Arms 13 Labouchere Channel 14 (ii) Middle regime 14 (aJ Salinity and temperature (b) OJrrents 14 (iii) Lower regime 14 (aJ 15 Salinity and temperature 15 (bJ OJrrents 15 (bJ Fitz Hugh Sound 16 (a) Salinlty and temperature (bJ CUrrents 16 (e) Nalau Passage 17 (dJ Fi sher Channel 17 18 IV. -

Inside Passage & Skeena Train

Northern Expedition Fraser River jetboat INSIDE PASSAGE & Activity Level: 2 SKEENA TRAIN June 30, 2022 – 8 Days 13 Meals Included: 5 breakfasts, 5 lunches, 3 dinners Includes grizzly bear watching at Fares per person: Khutzeymateen Sanctuary $3,265 double/twin; $3,835 single; $3,095 triple Please add 5% GST. Explore the stunning North Coast by land BC Seniors (65 & over): $115 discount with BC Services and sea! The 500-kilometre journey from Card; must book by April 28, 2022. Port Hardy to Prince Rupert aboard BC Experience Points: Ferries’ Northern Expedition takes 15 Earn 76 points on this tour. hours, all in daylight to permit great view- Redeem 76 points if you book by April 28, 2022. ing of the rugged coastline and abundant Departures from: Victoria wildlife. In Prince Rupert, we thrill to a 7- hour catamaran excursion to the Khutzeymateen Grizzly Sanctuary. Then we board VIA Rail’s Skeena Train for a spectac- ular all-day journey east to Prince George in deluxe ‘Touring Class’ with seating in the dome car. Experience the mighty Fraser River with a jetboat ride through Fort George Canyon. Then we drive south through the Cariboo with a visit to the historic gold rush town of Barkerville. Our last night is at the popular Harrison Hot Springs Resort with entertainment in the Copper Room. This is a wonderful British Columbia circle tour! ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, June 30 seals, sea lions, bald eagles, and blue herons as We drive north on the Island Highway, past we learn first-hand about this diverse marine en- Campbell River to Port Hardy. -

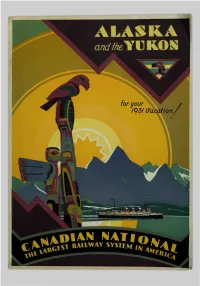

ALASKA and Fhe YC KON the UNIVERSITY of BRITISH COLUMBIA LIBRARY ASK A

i2L ALASKA and fhe YC KON THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA LIBRARY ASK A and the TRIANGLE TOUR o/°BRITISH COLUMBIA Printed in Canada ^•»A.% and true VII KOAT | « ALASKA BOUND » » By NORMAN REILLY RAINE* ERE it is once again—that uplifting excitement of going by- H water to strange places, of seeing and experiencing new things. Taxicabs and private cars converge on Vancouver's picturesque waterfront, and decant passengers and luggage on the long bright *NoRMAN REILLY RAINE pier, quick with the activities of sailing night. needs no introduction to the lover of short stories of the Above the shed arise masts, and three great funnels from which sea. He is recognized as the white steam plumes softly toward the summer stars. The gangway, author who found "Romance in Steam" while others were wedding commonplace to romance, leads into the vessel's bright still writing of the Clipper- ship days. Raine is at home interior where uniformed stewards wait, alert to serve. There is in the ports of the world— laughter, and a confusing clatter of tongues among the crowd on Europe, the South Seas— and now Canada's own the wharf; there are colored streamers of paper, hundreds of them, Pacific Coast. blowing in the night wind, and making an undulating carpet of tenuous communion between ship and shore. There is music, and farewells, broken by the deep-throated blare of the liner's whistle. An almost imperceptible trembling of the deck; a tightening and straightening of the bellying paper ribbons. Black water widens between the wharf and the ship's tall side, and the parted streamers ride gaily on the breeze. -

Indian and Non-Native Use of the Bulkley River an Historical Perspective

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians DFO - Library i MPO - Bibliothèque ^''entffique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I IIII III II IIIII II IIIIIIIIII II IIIIIIII 12020070 INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by Brendan O'Donnell Native Affairs Division Issue I Policy and Program Planning Ir, E98. F4 ^ ;.;^. 035 ^ no.1 ;^^; D ^^.. c.1 Fisher és Pêches and Oceans et Océans Cariad'â. I I Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians I Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I I INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE I USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER I AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1 by Brendan O'Donnell ^ Native Affairs Division Issue I 1 Policy and Program Planning 1 I I I I I E98.F4 035 no. I D c.1 I Fisheries Pêches 1 1*, and Oceans et Océans Canada` INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports onthe historical uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations have used these -rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Pacific Northwest LNG Project

Pacific NorthWest LNG Project Environmental Assessment Report September 2016 Cover photo credited to Pacific NorthWest LNG Ltd. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catalogue No: En106-136/2015E-PDF ISBN: 978-1-100-25630-6 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, and in any format, without charge or further permission. Unless otherwise specified, you may not reproduce materials, in whole or in part, for the purpose of commercial redistribution without prior written permission from the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H3 or info@ceaa- acee.gc.ca This document has been issued in French under the title: Projet de gaz naturel liquéfié Pacific NorthWest - Rapport d’évaluation environnementale Executive Summary Pacific NorthWest LNG Limited Partnership (the proponent) is proposing the construction, operation, and decommissioning of a new facility for the liquefaction, storage, and export of liquefied natural gas (LNG). The Pacific NorthWest LNG Project (the Project) is proposed to be located primarily on federal lands and waters administered by the Prince Rupert Port Authority approximately 15 kilometres south of Prince Rupert, British Columbia. At full production, the facility would receive approximately 3.2 billion standard cubic feet per day, or 9.1 x 107 cubic metres per day, of pipeline grade natural gas, and produce up to 20.5 million tonnes per annum of LNG for over 30 years. The Project would include the construction and operation of a marine terminal for loading LNG on to vessels for export to Pacific Rim markets in Asia. -

A Field Evaluation of Mink and River Otter on the Lower Columbia River and the Influence of Environmental Contaminants

Q N. ... / N / d,1%: : , *2 - - r - / . , O,; f; ~~~~~~- -, ~,, .F, , > U >{<XS '- -,A FIELD EVALUATION OF'MINK AND RIVER OWER ON THE. LOWERCOLUMBIA. RIVER AND-THENINFLtUENCE OF ENVIR'OMENTAL CONTAMINAN - . .- > t . l. /x4-, ,.K d ~ ~~~/F ~~~- z~ s-| l t Nf F* 5~ -L.* . -*-:.FINAL IEPORTi /- .' { > y - \~~~~~ -N j / .rn:ff )- . ' / W ' Submitted to-' / The Lowver CIumbia River Bi-State, "r Quality Program ' ' J " F-,,> - X .N>I../ Rob- ' e- ., -Chbrles .Heny' A;Grove,rRobert 6nd OlafRA:Hedstrom. * ' )' </. ' 'II Fore 'qnqRqngpland.Ecosystn8'6ibhcenterCe\! . , , ! '. ' ', . ' . , , . , / ' . t 4 ) S~~~I , -,, ,,; t> ., ., .i ' '< ' '>N'r6hlhest , , Reyseach-Station-':r.F, '. ,i,.'',,-''; i! .: '' j '. - 'O8', ' . 'O¢"- n ' 3080SE Cleby: /r rive ', . , N SI tI f, * * ,1\~~~-. < ii |? t<corvaili§,. , OR'--97333f"/tg,|, < i i '/F ODEQ -143-94, r 8 , . , .W~~~DE~ C950f08;: ,a.,, -, - :; : -, : ~febbtruary-12,j19i J /;' ; " ,_ ' /,i, 'Contracti~u~ .' , .. / ,,f' .-. ,- 1 . ,* -. ., i -Ftx , *;N fI )]., - F. , :.**, -iJ ;;4I ;;r\%';' \N-#~~~tjf40I~~v~svs~~tsrS~~l ltE<\ t < Lit 4s~ f A FIELD EVALUATION OF MINK AND RIVER OTTER ON THE LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER AND THE INFLUENCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS FINAL REPORT Submitted to: The Lower Columbia River Bi-State Water Quality Program by: Charles J. Henny, Robert A. Grove, and Olaf R. Hedstrom National Biological Service Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center 5Northwest Research Station 3080 SE Clearwater Drive Corvallis, OR 97333 Contract Numbers ODEQ 143-94 WDE C9500038 February 12, 1996 IRIVER OTTER AGE CLASS 0 _~~___ . £aQu~umiWaglt(.grarns -____......... 5.79 5.85 4.03 2.52 2.52 2.33 2.42 1.92 C EL .. -jS;EX,C'.......bC~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~........ -

Amends Letters Patent of Improvement Districts

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS AND HOUSING Local Government Act Ministerial Order No. M336 WHEREAS pursuant to the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. Reg 30/2010 the Local Government Act (the ‘Act’), the minister is authorized to make orders amending the Letters Patent of an improvement district; AND WHEREAS s. 690 (1) of the Act requires that an improvement district must call an annual general meeting at least once in every 12 months; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 further restrict when an improvement district must hold their annual general meetings; AND WHEREAS the Letters Patent for the improvement districts identified in Schedule 1 require that elections for board of trustee positions (the “elections”) must only be held at the improvement district’s annual general meeting; AND WHEREAS the timeframe to hold annual general meetings limits an improvement district ability to delay an election, when necessary; AND WHEREAS the ability of an improvement district to hold an election separately from their annual general meeting increases accessibility for eligible electors; ~ J September 11, 2020 __________________________ ____________________________________________ Date Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing (This part is for administrative purposes only and is not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Act and section: Local Government Act, section 679 _____ __ Other: Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, OIC 50/2010_ Page 1 of 7 AND WHEREAS, I, Selina Robinson, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, believe that improvement districts require the flexibility to hold elections and annual general meetings separately and without the additional timing restrictions currently established by their Letters Patent; NOW THEREFORE I HEREBY ORDER, pursuant to section 679 of the Act and the Improvement District Letters Patent Amendment Regulation, B.C. -

2016 Star Ratings and CCRPI Scores.Xlsx

2016 CCRPI Single Scores and School Climate Star Ratings Year System ID System Name School ID School Name CCRPI Single Score School Climate Star Rating 2016 601 Appling County 103 Appling County High School 81.3 3 2016 601 Appling County 177 Appling County Elementary School 67.5 3 2016 601 Appling County 195 Appling County Middle School 74 4 2016 601 Appling County 277 Appling County Primary School NA 4 2016 601 Appling County 1050 Altamaha Elementary School 79.8 4 2016 601 Appling County 5050 Fourth District Elementary School 63 4 2016 602 Atkinson County 103 Atkinson County High School 78.5 3 2016 602 Atkinson County 111 Atkinson County Middle School 69.2 4 2016 602 Atkinson County 187 Willacoochee Elementary School 85.3 4 2016 602 Atkinson County 190 Pearson Elementary School 74.2 4 2016 603 Bacon County 102 Bacon County Primary School NA 5 2016 603 Bacon County 202 Bacon County Middle School 64.6 4 2016 603 Bacon County 302 Bacon County High School 69.1 4 2016 603 Bacon County 3050 Bacon County Elementary School 82.1 4 2016 604 Baker County 105 Baker County K12 School 62.1 5 2016 605 Baldwin County 100 Oak Hill MS 59.1 3 2016 605 Baldwin County 104 Eagle Ridge Elementary School 54.1 3 2016 605 Baldwin County 189 Baldwin High School 77.8 3 2016 605 Baldwin County 194 Midway Elementary School 56.6 4 2016 605 Baldwin County 195 Blandy Hills Elementary School 62.8 4 2016 605 Baldwin County 199 Creekside Elementary School 69 4 2016 606 Banks County 105 Banks County Middle School 77.5 4 2016 606 Banks County 107 Banks County Elementary -

This City of Ours

THIS CITY OF OURS By J. WILLIS SAYRE For the illustrations used in this book the author expresses grateful acknowledgment to Mrs. Vivian M. Carkeek, Charles A. Thorndike and R. M. Kinnear. Copyright, 1936 by J. W. SAYRE rot &?+ *$$&&*? *• I^JJMJWW' 1 - *- \£*- ; * M: . * *>. f* j*^* */ ^ *** - • CHIEF SEATTLE Leader of his people both in peace and war, always a friend to the whites; as an orator, the Daniel Webster of his race. Note this excerpt, seldom surpassed in beauty of thought and diction, from his address to Governor Stevens: Why should I mourn at the untimely fate of my people? Tribe follows tribe, and nation follows nation, like the waves of the sea. It is the order of nature and regret is useless. Your time of decay may be distant — but it will surely come, for even the White Man whose God walked and talked with him as friend with friend cannot be exempt from the common destiny. We may be brothers after all. Let the White Man be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead — I say? There is no death. Only a change of worlds. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. BELIEVE IT OR NOT! 1 2. THE ROMANCE OF THE WATERFRONT . 5 3. HOW OUR RAILROADS GREW 11 4. FROM HORSE CARS TO MOTOR BUSES . 16 5. HOW SEATTLE USED TO SEE—AND KEEP WARM 21 6. INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS 26 7. PLAYING FOOTBALL IN PIONEER PLACE . 29 8. STRANGE "IFS" IN SEATTLE'S HISTORY . 34 9. HISTORICAL POINTS IN FIRST AVENUE . 41 10. -

Species at Risk Assessment—Pacific Rim National Park Reserve Of

Species at Risk Assessment—Pacific Rim National Park Reserve of Canada Prepared for Parks Canada Agency by Conan Webb 3rd May 2005 2 Contents 0.1 Acknowledgments . 10 1 Introduction 11 1.1 Background Information . 11 1.2 Objective . 16 1.3 Methods . 17 2 Species Reports 20 2.1 Sample Species Report . 21 2.2 Amhibia (Amphibians) . 23 2.2.1 Bufo boreas (Western toad) . 23 2.2.2 Rana aurora (Red-legged frog) . 29 2.3 Aves (Birds) . 37 2.3.1 Accipiter gentilis laingi (Queen Charlotte goshawk) . 37 2.3.2 Ardea herodias fannini (Pacific Great Blue heron) . 43 2.3.3 Asio flammeus (Short-eared owl) . 49 2.3.4 Brachyramphus marmoratus (Marbled murrelet) . 51 2.3.5 Columba fasciata (Band-tailed pigeon) . 59 2.3.6 Falco peregrinus (Peregrine falcon) . 61 2.3.7 Fratercula cirrhata (Tufted puffin) . 65 2.3.8 Glaucidium gnoma swarthi (Northern pygmy-owl, swarthi subspecies ) . 67 2.3.9 Megascops kennicottii kennicottii (Western screech-owl, kennicottii subspecies) . 69 2.3.10 Phalacrocorax penicillatus (Brandt’s cormorant) . 73 2.3.11 Ptychoramphus aleuticus (Cassin’s auklet) . 77 2.3.12 Synthliboramphus antiquus (Ancient murrelet) . 79 2.3.13 Uria aalge (Common murre) . 83 2.4 Bivalvia (Oysters; clams; scallops; mussels) . 87 2.4.1 Ostrea conchaphila (Olympia oyster) . 87 2.5 Gastropoda (Snails; slugs) . 91 2.5.1 Haliotis kamtschatkana (Northern abalone) . 91 2.5.2 Hemphillia dromedarius (Dromedary jumping-slug) . 95 2.6 Mammalia (Mammals) . 99 2.6.1 Cervus elaphus roosevelti (Roosevelt elk) . 99 2.6.2 Enhydra lutris (Sea otter) . -

The Fur Trade Era, 1770S–1849

Great Bear Rainforest The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The lives of First Nations people were irrevocably changed from the time the first European visitors came to their shores. The arrival of Captain Cook heralded the era of the fur trade and the first wave of newcomers into the future British Columbia who came from two directions in search of lucrative pelts. First came the sailors by ship across the Pacific Ocean in pursuit of sea otter, then soon after came the fort builders who crossed the continent from the east by canoe. These traders initiated an intense period of interaction between First Nations and European newcomers, lasting from the 1780s to the formation of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, when the business of trade was the main concern of both parties. During this era, the newcomers depended on First Nations communities not only for furs, but also for services such as guiding, carrying mail, and most importantly, supplying much of the food they required for daily survival. First Nations communities incorporated the newcomers into the fabric of their lives, utilizing the new trade goods in ways which enhanced their societies, such as using iron to replace stone axes and guns to augment the bow and arrow. These enhancements, however, came at a terrible cost, for while the fur traders brought iron and guns, they also brought unknown diseases which resulted in massive depopulation of First Nations communities. European Expansion The northwest region of North America was one of the last areas of the globe to feel the advance of European colonialism.