TRAGEDY, OUTRAGE & REFORM Crimes That Changed Our World: 1911 – Triangle Factory Fire – Building Safety Codes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Escapes in Urban America: History and Preservation

FIRE ESCAPES IN URBAN AMERICA: HISTORY AND PRESERVATION A Thesis Presented by Elizabeth Mary André to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Historic Preservation February, 2006 Abstract For roughly seventy years, iron balcony fire escapes played a major role in shaping urban areas in the United States. However, we continually take these features for granted. In their presence, we fail to care for them, they deteriorate, and become unsafe. When they disappear, we hardly miss them. Too often, building owners, developers, architects, and historic preservationists consider the fire escape a rusty iron eyesore obstructing beautiful building façades. Although the number is growing, not enough people have interest in saving these white elephants of urban America. Back in 1860, however, when the Department of Buildings first ordered the erection of fire escapes on tenement houses in New York City, these now-forgotten contrivances captivated public attention and fueled a debate that would rage well into the twentieth century. By the end of their seventy-year heyday, rarely a building in New York City, and many other major American cities, could be found that did not have at least one small fire escape. Arguably, no other form of emergency egress has impacted the architectural, social, and political context in metropolitan America more than the balcony fire escape. Lining building façades in urban streetscapes, the fire escape is still a predominant feature in major American cities, and one has difficulty strolling through historic city streets without spotting an entire neighborhood hidden behind these iron contraptions. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

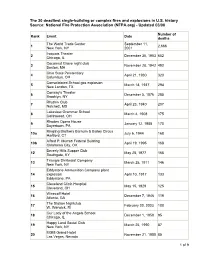

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.Org) - Updated 03/08

The 20 deadliest single-building or complex fires and explosions in U.S. history Source: National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.org) - Updated 03/08 Number of Rank Event Date deaths The World Trade Center September 11, 1 2,666 New York, NY 2001 Iroquois Theater 2 December 30, 1903 602 Chicago, IL Cocoanut Grove night club 3 November 28, 1942 492 Boston, MA Ohio State Penitentiary 4 April 21, 1930 320 Columbus, OH Consolidated School gas explosion 5 March 18, 1937 294 New London, TX Conway's Theater 6 December 5, 1876 285 Brooklyn, NY Rhythm Club 7 April 23, 1940 207 Natchez, MS Lakeview Grammar School 8 March 4, 1908 175 Collinwood, OH Rhodes Opera House 9 January 12, 1908 170 Boyertown, PA Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus 10a July 6, 1944 168 Hartford, CT Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building 10b April 19, 1995 168 Oklahoma City, OK Beverly Hills Supper Club 12 May 28, 1977 165 Southgate, KY Triangle Shirtwaist Company 13 March 25, 1911 146 New York, NY Eddystone Ammunition Company plant 14 explosion April 10, 1917 133 Eddystone, PA Cleveland Clinic Hospital 15 May 15, 1929 125 Cleveland, OH Winecoff Hotel 16 December 7, 1946 119 Atlanta, GA The Station Nightclub 17 February 20, 2003 100 W. Warwick, RI Our Lady of the Angels School 18 December 1, 1958 95 Chicago, IL Happy Land Social Club 19 March 25, 1990 87 New York, NY MGM Grand Hotel 20 November 21, 1980 85 Las Vegas, Nevada 1 of 9 Major Building Fires Source: Report on Large Building Fires and Subsequent Code Changes Jim Arnold, Assoc. -

Chapter 10 of the Housing Choice Voucher Program Guidebook

Table of Contents CHAPTER 10....................................................................................................................... 10-1 CHAPTER 10 HOUSING QUALITY STANDARDS...................................................... 10-1 10.1 Chapter Overview................................................................................................... 10-1 10.2 Housing Quality Standards General Requirements................................................. 10-1 10.3 Performance Requirements And Acceptability Standards ..................................... 10-3 Sanitary Facilities........................................................................................................... 10-3 Food Preparation and Refuse Disposal .......................................................................... 10-4 Space and Security......................................................................................................... 10-6 Thermal Environment .................................................................................................... 10-7 Illumination and Electricity............................................................................................ 10-8 Structure and Materials .................................................................................................. 10-9 Interior Air Quality ...................................................................................................... 10-10 Water Supply............................................................................................................... -

Basic Fire Escape Planning for Your Home

BASIC FIRE ESCAPE PLANNING FOR YOUR HOME Pull together everyone in your household and make a plan. Walk through your home and inspect all possible exits and escape routes. Households with children should consider drawing a floor plan of your home, marking two ways out of each room, including windows and doors. Also, mark the location of each smoke alarm. For easy planning, download NFPA's escape planning grid (PDF, 1.1 MB). This is a great way to get children involved in fire safety in a non-threatening way. A closed door may slow the spread of smoke, heat and fire. Install smoke alarms in every sleeping room, outside each sleeping area and on every level of the home. NFPA 72, National Fire Alarm Code® requires interconnected smoke alarms throughout the home. When one sounds, they all sound. Everyone in the household must understand the escape plan. When you walk through your plan, check to make sure the escape routes are clear and doors and windows can be opened easily. Choose an outside meeting place (i.e. neighbor's house, a light post, mailbox, or stop sign) a safe distance in front of your home where everyone can meet after they've escaped. Make sure to mark the location of the meeting place on your escape plan. Go outside to see if your street number is clearly visible from the road. If not, paint it on the curb or install house numbers to ensure that responding emergency personnel can find your home. Have everyone memorize the emergency phone number of the fire department. -

The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront

The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront: A Proposal for Preservation to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission September, 2004 Submitted by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street New York, NY 10003 212/475-9585 www.gvshp.org The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront: Proposal to the Landmarks Preservation Commission Introduction The Far West Village, located along the Hudson River waterfront between Horatio and Barrow Streets, is where Greenwich Village began, home to its earliest European settlements. Within its dozen or so blocks can be found a treasure trove of historic buildings and resources spanning about a hundred years and a broad range of styles and building types. However, the district’s character is united by several overarching commonalities and punctuated by several distinctive features that define its unique significance, including: its role as a unique intact record of the only mixed maritime/industrial and residential neighborhood along the Hudson River waterfront; its unusually large collection of several maritime, industrial, and residential building types not found elsewhere; its collection of several buildings which were pioneering instances of adaptive re-use of industrial buildings for residential purposes; its numerous key industrial complexes which shaped New York City’s development; the particular buildings and streets within its boundaries which served as a record of several important moments in the history of industry, shipping, and New York City; and several exceptional buildings which are noteworthy due to their age, unique composition, early manifestation of a subsequently common building type, or historical and architectural significance. -

Maintenance Checklist) Revised February 26, 2014

DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING INSPECTION Housing Inspection Services City and County of San Francisco 1660 Mission Street, 6th Floor, San Francisco, California 94103-2414 Phone: (415) 558-6220 Fax :( 415) 558-6249 Department Website: www.sfdbi.org RESIDENTIAL HABITIBILITY INFORMATION SAN FRANCISCO HOUSING CODE REQUIREMENTS (PROPERTY OWNER MAINTENANCE CHECKLIST) REVISED FEBRUARY 26, 2014 FOR ONE & TWO FAMILY DWELLINGS, APARTMENT HOUSES (3 OR MORE DWELLING UNITS) & RESIDENTIAL/TOURIST HOTELS 1. SEC. 605. PROHIBITION ON WOODEN FIXED UTILITY LADDERS Wooden Fixed Utility Ladders shall be prohibited on buildings which contain R-1, R-2, and R-3 Occupancies (hotels and apartment house [and dwellings), as defined by Chapter 4 of this Code. "Fixed Utility Ladder" shall mean any ladder permanently attached to the exterior of a structure or building, but shall not include ladders required by the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health for workplace safety that have been installed with a proper permit, or ladders expressly authorized by the Department of Building Inspection for Building Code or Fire Code compliance purposes. Wooden Fixed Utility Ladders shall be removed or replaced with metal ladders that comply with applicable Building, Fire, and Housing Code requirements. 2. MAINTAIN CLEAR & UNOBSTRUCTED MEANS OF EGRESS: Please keep all means of egress, primary (front stairs, exit corridors), and secondary (rear stairs, fire escapes) free from encumbrances (such as storage, flower pots, household items, laundry lines, and any tripping hazards). These paths of travel are to be completely clear at all times for emergency exiting. 3. MAINTAIN FIRE ESCAPES: Check all fire escape ladders to ensure that they are fully operational (in particular the cable and all moving parts) and that drop ladders are not obstructed. -

The Collinwood School Fire of 1908

H. F. Wendell Company, Leipsic, Ohio Mourning Card, 1902 ca. 1920 Gilt printing on white card stock; 4 ¼ x 6 ½ inches The mourning, or memorial, card reprinted on the cover was used by the funeral industry from 1902 to around 1920. Mourning cards became popular during the Victorian era and were often kept as reminders of lost friends or family members. Cards for children were typically printed on white cardboard, whereas cards for older people were printed on black cardboard. In reprinting this original card, the Library made no changes except for the wording in the center box, which typically would have contained the name of the deceased along with his or her birth and death dates. Reproduced courtesy of the Museum of Funeral Customs, Springfield, Illinois, www.funeralmuseum.org The Last Lesson Cleveland Plain Dealer, 6 March 1908 In Loving Remembrance: The Collinwood School Fire of 1908 An exhibit prepared by the History & Geography Department, Cleveland Public Library The Collinwood School Fire remains the worst school building fire in U.S. history. This is perhaps due to the heightened consciousness regarding fire safety following the disaster, but more concretely to the stricter building codes, better construction materials and lifesaving devices which came into use after the fire. A century-old myth holds that the students at Collinwood died because they were trapped behind doors that opened inward. This was quickly proven to be false, but the myth gained traction and is repeated to this day. It was the narrowness of the exit stairs and inner vestibule doorway, combined with the panic of the children as they rushed to escape, that led to their entrapment. -

Fire Escapes

PORTLAND FIRE & RESCUE APRIL 30, 2020 FIR 2.08 - FIRE ESCAPES I. SCOPE A. This policy is established February 12, 2008, and replaces previous policies CE B-3, B-9, and B-12. This policy combines elements from all three policies, the 2016 Portland Fire Code, and the 2019 Oregon Structural Specialty Code into this single document. B. It is the purpose of this policy to: 1. Establish procedures for the inspection, evaluation and testing of fire escapes, and to provide information pertaining to the acceptable methods of repair when needed. 2. Address the process for removal of counterbalance stairs. 3. Address the removal of fire escapes. C. This policy applies to all structures where Portland Fire & Rescue (PF&R) has authority. D. The City of Portland currently has more than 600 fire escapes that are attached to existing buildings and are part of the required emergency egress system or serve as firefighting platforms. Many of these fire escapes and the buildings they are attached to are very old. Without routine maintenance, deterioration can result in fire escapes becoming unsafe for use by occupants or firefighters during an emergency. E. Counterbalance stairs allow occupants to exit fire escape platforms. Some building owners request the removal of counterbalance stairs to prohibit unauthorized use for entry into buildings. This policy provides guidance to resolving this public safety issue. F. When exit systems throughout a building are upgraded, an owner may request removal of existing exterior fire escapes as part of the commercial building permit process. II. SPECIFIC A. References 1. Portland City Code (PCC) Title 31, 31.20.080 2. -

The Collinwood School Fire Tragedy and Its Impact on Fire Safety

Collinwood’s Call to Action: The Collinwood School Fire Tragedy and Its Impact on Fire Safety Ehren Collins Historical Paper Junior Division Word Count: 2498 On March 4, 1908, a massive fire erupted in an elementary school in Collinwood, Ohio, killing 172 children and three adults. Though the children attended a relatively new school, their building and its inadequate fire protection contributed significantly to the loss of innocent lives. This horrific tragedy in a small Ohio town awoke the entire nation to the inadequacy of fire safety practices in schools, sparking a call to action to standardize fire safety measures and impel city and state governments to implement safety features lacking in Ohio schools and schools across the country. From this tragedy, the entire nation took notice, setting in motion an era of redevelopment of fire safety measures, still credited to the Collinwood disaster today. Collinwood was a small town established in 1874 just east of Cleveland. The town began as a single railroad stop chosen by the Lakeshore and Michigan Southern Railway Company given its central location between Buffalo and Toledo. The establishment of the Collinwood Rail Yards attracted immigrants seeking jobs in the railroad industry. Collinwood grew into a diverse ethnic community, housing large Italian, Irish, and Slovenian populations (“South Collinwood” 1). By 1899, Collinwood had its own school system, newspaper, six churches, plentiful business, and even an amusement park. In 1901, a small, four story school was built on Collamer Street in North Collinwood. Lake View School was updated in 1907, adding four rooms to the rear of the building (“In Loving Remembrance” 1-2) (See Appendix 1). -

Fire Escape Testing and Maintenance Policy 08-08 References: 2007 OFC 1027.16, 2007 OSSC 3404

Office of the Fire Marshal 1320 Willamette St. (541) 682-5411 Fire Escape Testing and Maintenance Policy 08-08 References: 2007 OFC 1027.16, 2007 OSSC 3404 Scope This policy presents an explanation and summary of the OFC and OSSC maintenance and testing requirements for fire escapes. OFC 1027.16.5 Materials and Strength: The fire code official is authorized to require testing or other satisfactory evidence that an existing fire escape stair meets the requirement of this section. References 1. 2007 Oregon Fire Code (OFC) Chapter 10, 1027.16 2. 2007 Oregon Structural Specialty Code (OSSC) Chapter 34, 3404 3. Oregon Revised Statutes (ORS) 479 4. 1982 UBC Appendix 1 section 111 and UFC Appendix 1-A section 2(d) General 1. This policy is established May 28, 2008 but reflects code expectations that have been in effect as noted in the reference list. 2. It is the purpose of this policy to establish 1) procedures for the inspection, testing and certification of fire escapes, as well as providing information pertaining to acceptable methods of repair when needed; 2) the process for the removal of counterbalance stairs; and 3) the removal of fire escapes. 3. The city of Eugene has fire escapes that are attached to existing buildings and are part of the required emergency egress system or serve as firefighting platforms. Many of these fire escapes and the buildings they are attached to are very old. Through natural disintegration and/or neglect many of these fire escapes have fallen into a state of disrepair and may be unsafe if used by the occupants or by firefighters during an emergency. -

TEACHER's GUIDE All Primary Source Documents

TEACHER’S GUIDE All Primary Source Documents MISSION 4: “City of Immigrants” Table of Contents Part 1 1. List of Passengers on the Batavia………………….….…………………………………………………………..……………………p. 1 2. Pauline Newman Describes Her Family’s Journey to New York City………………….…………………………...................….p. 2 3. Ellis Island Eye Inspection Photo……………………………………………………………………………..……………………….p. 4 4. Sylvia Bernstein on Arriving at Ellis Island……………………………………………….……………………………………...…..p. 5 5. Table of Immigrant Origins, 1880-1920………………………………………………………………………………….....................p. 7 6. “The High Tide of Immigration – A National Menace”……………………………………………………..……………………...p. 8 7. “The Surrender of New York Town” Cartoon……………………………………………………………………………………….p. 9 Part 2 1. An Immigrant Writes to the Bintel Brief for Advice………………………….………………………………………….………...p. 10 2. Report on Food Expenses for a Working Family in 1909……..…………………………………………………………..……….p. 11 3. Garment Workers in a Home Sweatshop Photo……………………………………………...……………..……………………..p. 12 4. Floor Plan of a Typical Tenement, c. 1905...........................................................................................................................................p. 13 5. “Immigration and the Public Health” Article...……..…………………………………………………………………………..….p. 14 6. Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society Magazine Cover..…………................................………………………………………..……….p. 15 Part 3 1. Lillian Ward on Establishing the Henry Street Settlement...............................................................................................................p.