TEACHER's GUIDE All Primary Source Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940)

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940) Nursing is love in action, and there is no finer manifestation of it than the care of the poor and disabled in their own homes Lillian D. Wald was a nurse, social worker, public health official, teacher, author, editor, publisher, women's rights activist, and the founder of American community nursing. Her unselfish devotion to humanity is recognized around the world and her visionary programs have been widely copied everywhere. She was born on March 10, 1867, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of four children born to Max and Minnie Schwartz Wald. The family moved to Rochester, New York, and Wald received her education in private schools there. Her grandparents on both sides were Jewish scholars and rabbis; one of them, grandfather Schwartz, lived with the family for several years and had a great influence on young Lillian. She was a bright student, completing high school when she was only 15. Wald decided to travel, and for six years she toured the globe and during this time she worked briefly as a newspaper reporter. In 1889, she met a young nurse who impressed Wald so much that she decided to study nursing at New York City Hospital. She graduated and, at the age of 22, entered Women's Medical College studying to become a doctor. At the same time, she volunteered to provide nursing services to the immigrants and the poor living on New York's Lower East Side. Visiting pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled in their homes, Wald came to the conclusion that there was a crisis in need of immediate redress. -

Fire Escapes in Urban America: History and Preservation

FIRE ESCAPES IN URBAN AMERICA: HISTORY AND PRESERVATION A Thesis Presented by Elizabeth Mary André to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Historic Preservation February, 2006 Abstract For roughly seventy years, iron balcony fire escapes played a major role in shaping urban areas in the United States. However, we continually take these features for granted. In their presence, we fail to care for them, they deteriorate, and become unsafe. When they disappear, we hardly miss them. Too often, building owners, developers, architects, and historic preservationists consider the fire escape a rusty iron eyesore obstructing beautiful building façades. Although the number is growing, not enough people have interest in saving these white elephants of urban America. Back in 1860, however, when the Department of Buildings first ordered the erection of fire escapes on tenement houses in New York City, these now-forgotten contrivances captivated public attention and fueled a debate that would rage well into the twentieth century. By the end of their seventy-year heyday, rarely a building in New York City, and many other major American cities, could be found that did not have at least one small fire escape. Arguably, no other form of emergency egress has impacted the architectural, social, and political context in metropolitan America more than the balcony fire escape. Lining building façades in urban streetscapes, the fire escape is still a predominant feature in major American cities, and one has difficulty strolling through historic city streets without spotting an entire neighborhood hidden behind these iron contraptions. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

THE CITY of NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4Th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533 -5300 - [email protected]

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533 -5300 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] Jamie Rogers, Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager District Needs Statement for Fiscal Year 2019 Introduction Community Board 3 Manhattan spans the East Village, Lower East Side, and a vast amount of Chinatown. It is bounded by 14th Street to the north, the East River to the east, the Brooklyn Bridge to the south, and Fourth Avenue and the Bowery to the west, extending to Baxter and Pearl Streets south of Canal Street. This community is filled with a diversity of cultures, religions, incomes, and languages. Its character comes from its heritage as a historic and present day first stop for many immigrants. CD 3 is one of the largest board Districts and is the fourth most densely populated District, with approximately 164,063 people.1 Our residents are very proud of their historic and diverse neighborhood, however, the very characteristics that make this District unique also make it a challenging place to plan and ensure services for all residents and businesses. Demographic Change The CD 3 population is changing in many ways. The 2000 census reported that 23% of our population, over 38,000 of our residents, required income support. By 2014, this number had jumped to about 41% of the total population, over 68,000 persons.2 The number of people receiving Medicaid-only assistance also continues to increase, climbing from 45,724 in 20053 to more than 48,200 people currently.4 Our community is an example of the growing income inequality that is endemic in New York City. -

Henry Street

2014 GALA DINNER DANCE Henry Street’s sold-out 2014 Gala Dinner Dance — attended by 400 of New York’s best, brightest and most influential leaders — honored Amandine and Stephen Freidheim, Chief Investment Officer, Founder and Managing Partner of Cyrus Capital Partners, from Fir Tree Partners, a New York based private investment firm, and NEWS Alexis Stoudemire, President of the Amar’e & Alexis Stoudemire Foundation. The glamorous gala, held at the Plaza Hotel, reaped more than $1 million to benefit the Settlement’s programs. Nearly $167,000 HENRY STREET 2015 265 HENRY STREET, NEW YORK NY 10002 212.766.9200 WWW.HENRYSTREET.ORG was raised at the live auction conducted by Tash Perrin of Christie’s. Co-chairs were Enrica Arengi Bentivoglio, Barbara von THE ART SHOW Bismarck, Giovanna Campagna, Natalia Gottret Echavarria, Kalliope Karella, Anna Pinheiro, Pilar Crespi Robert and Lesley Beautiful people — philanthropists, art enthusiasts, and 7 Schulhof. Mulberry was the corporate sponsor. The Playhouse Jay Wegman, business, cultural and civic leaders — and beautiful works of Director of the The 2015 Gala Dinner Dance will be held on April 14. Abrons Arts Center, art filled the Park Avenue Armory on March 4, 2014, for the Celebrates a Century Please call 212.766.9200 x247 to request an invitation. with the Obie award. 26th Annual Art Show. of Performance Spotted among the Gala Preview guests were artist Christo, From the moment Henry Street’s Franklin Furnace founder Martha Wilson and tennis star Neighborhood Playhouse opened John McEnroe. in 1915, the performances on Honorary Chair of the event was Agnes Gund. -

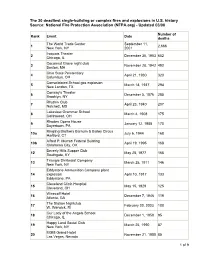

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.Org) - Updated 03/08

The 20 deadliest single-building or complex fires and explosions in U.S. history Source: National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.org) - Updated 03/08 Number of Rank Event Date deaths The World Trade Center September 11, 1 2,666 New York, NY 2001 Iroquois Theater 2 December 30, 1903 602 Chicago, IL Cocoanut Grove night club 3 November 28, 1942 492 Boston, MA Ohio State Penitentiary 4 April 21, 1930 320 Columbus, OH Consolidated School gas explosion 5 March 18, 1937 294 New London, TX Conway's Theater 6 December 5, 1876 285 Brooklyn, NY Rhythm Club 7 April 23, 1940 207 Natchez, MS Lakeview Grammar School 8 March 4, 1908 175 Collinwood, OH Rhodes Opera House 9 January 12, 1908 170 Boyertown, PA Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus 10a July 6, 1944 168 Hartford, CT Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building 10b April 19, 1995 168 Oklahoma City, OK Beverly Hills Supper Club 12 May 28, 1977 165 Southgate, KY Triangle Shirtwaist Company 13 March 25, 1911 146 New York, NY Eddystone Ammunition Company plant 14 explosion April 10, 1917 133 Eddystone, PA Cleveland Clinic Hospital 15 May 15, 1929 125 Cleveland, OH Winecoff Hotel 16 December 7, 1946 119 Atlanta, GA The Station Nightclub 17 February 20, 2003 100 W. Warwick, RI Our Lady of the Angels School 18 December 1, 1958 95 Chicago, IL Happy Land Social Club 19 March 25, 1990 87 New York, NY MGM Grand Hotel 20 November 21, 1980 85 Las Vegas, Nevada 1 of 9 Major Building Fires Source: Report on Large Building Fires and Subsequent Code Changes Jim Arnold, Assoc. -

Klezmerquerque 2015

KlezmerQuerque 2015 Jake Shulman-Ment: Violin and Yiddish Song Born in New York City, violinist Jake Shulman-Ment is among the leaders of a new generation of Klezmer and Eastern European folk music performers. He has performed and recorded internationally with Daniel Kahn and the Painted Bird, Di Naye Kapelye, Adrian Receanu, The Other Europeans, Frank London, Duncan Sheik, David Krakauer, Alicia Svigals, Michael Alpert, Deborah Strauss, Jeff Warschauer, Adrienne Cooper, Margot Leverett and the Klezmer Mountain Boys and many more. An internationally in-demand teacher, Jake has been a faculty member of New York’s Henry Street Settlement, KlezKamp, KlezKanada, Klezmer Paris, the Krakow Jewish Culture Festival, Yiddish Summer Weimar, and other festivals around the globe. An avid traveler, Jake has made several extended journeys to collect, study, perform, and document traditional folk music in Hungary, Romania, and Greece. In 2010 Jake received a Fulbright research grant to collect, study, perform, and document traditional music in Romania. His wide range of styles includes klezmer, classical, Romanian, Hungarian, Gypsy, and Greek. His classical music experience has consisted of performances with orchestras and chamber music groups throughout New York and New England, as well as study with internationally renowned concert artist Gerald Beal and widely acclaimed violin pedagogue Joey Corpus. Jake has created, directed, and performed music for a number of theater pieces, including several shows with theatrical wizard Jenny Romaine of Great Small Works, and the Folksbiene Yiddish Theater. He co-founded and regularly performs at “Tantshoyz,” New York's monthly Yiddish dance party sponsored by the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, and is frequently invited to accompany dance workshops led by Yiddish dance master and world-renowned ethnomusicologist Walter Zev Feldman. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

Henry Street Fall 2007 265 Henry Street, New York NY 10002 212.766.9200

NEWS from HENRY STREET FALL 2007 265 HENRY STREET, NEW YORK NY 10002 212.766.9200 WWW.HENRYSTREET.0RG Off to College! Back to School with Henry Street Thanks, Henry Street What do rocket science, rugby tournaments, youth employment and a college prep “Henry Street has given me so program have in common? They’re all happening at Henry Street Settlement this fall. many opportunities,” says 18-year- Regardless of age or interests, there’s something for every young person at Henry old Jessica Ramos, a freshman Street. Programming is in full swing at the early childhood education centers, after- at her top college choice—SUNY Stony Brook. school programs, and adolescent programs, and planning is already underway for Henry Street’s Expanded Horizons the 2008 summer camp season. college prep program provided the counseling and support Jessica After School needed to choose schools that Exciting activities in after-school programs matched her goals and to stay this year include a new rocket science class, motivated during a high-pressure swimming at the local Y and a new community time. Henry Street staff encouraged service project in partnership with the ACA her to consider options where she MAN Gallery. Through the project, children will create SS could become more independent RO bookmarks that will be exhibited in Toronto to G by living away from home. “This D I V was the most important advice raise funds to restock libraries in Afghanistan. T/DA H that Henry Street gave me,” says Also back by popular demand is “High School is Jessica. -

Chapter 10 of the Housing Choice Voucher Program Guidebook

Table of Contents CHAPTER 10....................................................................................................................... 10-1 CHAPTER 10 HOUSING QUALITY STANDARDS...................................................... 10-1 10.1 Chapter Overview................................................................................................... 10-1 10.2 Housing Quality Standards General Requirements................................................. 10-1 10.3 Performance Requirements And Acceptability Standards ..................................... 10-3 Sanitary Facilities........................................................................................................... 10-3 Food Preparation and Refuse Disposal .......................................................................... 10-4 Space and Security......................................................................................................... 10-6 Thermal Environment .................................................................................................... 10-7 Illumination and Electricity............................................................................................ 10-8 Structure and Materials .................................................................................................. 10-9 Interior Air Quality ...................................................................................................... 10-10 Water Supply............................................................................................................... -

Basic Fire Escape Planning for Your Home

BASIC FIRE ESCAPE PLANNING FOR YOUR HOME Pull together everyone in your household and make a plan. Walk through your home and inspect all possible exits and escape routes. Households with children should consider drawing a floor plan of your home, marking two ways out of each room, including windows and doors. Also, mark the location of each smoke alarm. For easy planning, download NFPA's escape planning grid (PDF, 1.1 MB). This is a great way to get children involved in fire safety in a non-threatening way. A closed door may slow the spread of smoke, heat and fire. Install smoke alarms in every sleeping room, outside each sleeping area and on every level of the home. NFPA 72, National Fire Alarm Code® requires interconnected smoke alarms throughout the home. When one sounds, they all sound. Everyone in the household must understand the escape plan. When you walk through your plan, check to make sure the escape routes are clear and doors and windows can be opened easily. Choose an outside meeting place (i.e. neighbor's house, a light post, mailbox, or stop sign) a safe distance in front of your home where everyone can meet after they've escaped. Make sure to mark the location of the meeting place on your escape plan. Go outside to see if your street number is clearly visible from the road. If not, paint it on the curb or install house numbers to ensure that responding emergency personnel can find your home. Have everyone memorize the emergency phone number of the fire department. -

The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront

The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront: A Proposal for Preservation to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission September, 2004 Submitted by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street New York, NY 10003 212/475-9585 www.gvshp.org The Far West Village and Greenwich Village Waterfront: Proposal to the Landmarks Preservation Commission Introduction The Far West Village, located along the Hudson River waterfront between Horatio and Barrow Streets, is where Greenwich Village began, home to its earliest European settlements. Within its dozen or so blocks can be found a treasure trove of historic buildings and resources spanning about a hundred years and a broad range of styles and building types. However, the district’s character is united by several overarching commonalities and punctuated by several distinctive features that define its unique significance, including: its role as a unique intact record of the only mixed maritime/industrial and residential neighborhood along the Hudson River waterfront; its unusually large collection of several maritime, industrial, and residential building types not found elsewhere; its collection of several buildings which were pioneering instances of adaptive re-use of industrial buildings for residential purposes; its numerous key industrial complexes which shaped New York City’s development; the particular buildings and streets within its boundaries which served as a record of several important moments in the history of industry, shipping, and New York City; and several exceptional buildings which are noteworthy due to their age, unique composition, early manifestation of a subsequently common building type, or historical and architectural significance.