Corporate Organization and the Design Big Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We're Still LENDING

INSIDE Health & Fitness MAY 6, 2010 SentineNORTH BRUNSWICK • SOUTH BRUNSWICK l gmnews.com 50< S.B. introduces budget with 8c tax increase Council assures public that there is still much work to be done BY JENNIFER BOOTON Staff Writer "though the South Brunswick Town- ship Council introduced a municipal T budget last week that carries an 8-cent tax increase, officials were sure to note that there is still much work to be done. The budget introduced on April 27 ab- sorbs an unexpected $1.1 million slash in state aid. The township took a 17.5 percent hit in its energy tax receipts, which brought expected state revenue down from $6.4 mil- lion last year to $5.2 million this year. "Budget problems in Trenton get fixed in the suburbs, not in Trenton," said Deputy Mayor Chris Killmurray. "The playing field is not level with Trenton, but we have to deal with it. " The $46 million budget was introduced last week for statutory purposes, since the state requires municipalities to introduce their budgets by May 11, but it will most likely see many amendments before the public hearing and possible adoption on June 22, according to Township Manager Matthew Watkins. "While you're introducing this today in April, we're not looking for a final adoption on this for some time," Watkins said to the SCOTT (TRIEDMAN council. "We reworked some of the budget, Ryan Kloos, 13, of East Brunswick, checks out a huge towing truck from l,x>gan Towing of North Brunswtek during the IG** annual North (Continued on page 38) Brunswick Cops & Rodders car show at DeVry University Sunday. -

Brands We Love

Brands We Love # D I N T DENIM 3.1 PHILLIP LIM DANSKO IRO NICOLE MILLER THEORY AG 360 CASHMERE DAVID YURMAN ISABEL MARANT NILI LOTAN THE GREAT AGOLDE We Do Not Accept: DEREK LAM ISSEY MIYAKE NO 6 STORE THE ROW AMO DL1961 NORTH FACE TIBI CITIZENS OF HUMANITY ABERCROMBIE & FITCH H&M A DOLCE & GABBANA TIFFANY & CO CURRENT/ELLIOTT AMERICAN APPAREL HOLLISTER ACNE STUDIOS AMERICAN EAGLE HOT TOPIC DONNA KARAN J TOCCA DL1961 ANN TAYLOR AG INC DOSA J BRAND O TOD’S FRAME ANGIE JACLYN SMITH AGL DRIES VAN NOTEN J CREW OBAKKI TOM FORD GOLDSIGN APT 9 JOE BOXER AGOLDE DVF JAMES PERSE OFFICINE CREATIVE TOP SHOP HUDSON ATTENTION JUICY COUTURE ALAIA JEAN PAUL GAULTIER OPENING CEREMONY AX PARIS LAND’S END TORY BURCH J BRAND BANANA REPUBLIC ALC OSCAR DE LA RENTA LOVE 21 JIL SANDER TRINA TURK JOES BDG LUX ALEXANDER MCQUEEN E JIMMY CHOO LEVIS BEBE MAX STUDIO ALEXANDER WANG EILEEN FISHER JOIE MOTHER BLUES METAPHOR BONGO ALICE & OLIVIA EMANUEL UNGARO P U MOUSSY MISS ME PAIGE CANDIE’S MISS TINA ANNA SUI ELIZABETH & JAMES UGG PAIGE CANYON RIVER PARKER MOSSIMO ANN DEMEULEMEESTER EMILIO PUCCI K ULLA JOHNSON R13 CATALINA NICKI MINAJ ANTHROPOLOGIE BRANDS ENZA COSTA KATE SPADE PATAGONIA RE/DONE CATHY DANIELS OLD NAVY ATM ERDEM PIERRE HARDY CHAPS ROCK & REPUBLIC SIMON MILLER CHARLOTTE RUSSE AUTUMN CASHMERE EVERLANE PRADA ROUTE 66 V CHIC ROXY AVANT TOI L PROENZA SCHOULER VALENTINO CHICOS L’AGENCE SAG HARBOR VANESSA BRUNO ATHLETIC CHRISTINALOVE SIMPLY VERA WANG F LANVIN VELVET ALO COVINGTON SO... CROFT & BARROW FENDI LEM LEM R VERONICA BEARD ATHLETA SONOMA LEVIS RACHEL COMEY DAISY FUENTES SOFIA VERGARA B FIORENTINI + BAKER VERSACE LULULEMON DANSKIN LOEFFLER RANDALL RAG & BONE STUDIO TAHARI BABATON FREE PEOPLE VICTORIA BECKHAM OUTDOOR VOICES ECOTE TARGET BALENCIAGA FRYE LOEWE RAILS VINCE NORTH FACE ELLE URBAN OUTFITTERS ETC.. -

Here Comes the Budget Bride the Biggest News in Fashion This Week Isn’T on the Milan Runways

The Inside: Pg. 18 ICAHN’S FEDERATED MOVE/3 KELLWOOD’S BUY/3 Where LoyaltyWWD Lies WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’THURSDAY Daily Newspaper • September 28, 2006 • $2.00 List Sportswear Here Comes the Budget Bride The biggest news in fashion this week isn’t on the Milan runways. Rather, it hails from the wonderful world of high- low, where Viktor & Rolf and H&M have gotten hitched for a short-term marriage. It’s that very idea that inspired Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren, who discussed details of the collaboration exclusively with WWD. The ultimate object of their wedded bliss: this 298 euro, or $380, wedding gown, pictured here with Horsting and Snoeren in the ad campaign shot by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin. For more on the season, see pages 6 to 9. Chloé to Name Marni’s Paolo Melin Anderson as Head Designer By Miles Socha French fashion house later this about its succession plan after its hloé has tapped a senior, but year. show during Paris Fashion Week. Chidden, talent from Marni to Reached late on Wednesday, a Anderson, a Swedish native who succeed Phoebe Philo, WWD has Chloé spokesman said only, “We has worked at Marni for several learned. do not comment on rumors.” years, will assume the design According to sources, Paolo However, the house said recently helm at one of the fastest-growing Melin Anderson will join the it would make an announcement See Chloé, Page 10 WWDTHURSDAYWWD.COM Sportswear FASHION ™ For better or worse, themes played a big role in the Milan collections, from a silvery space theme to a football game to a fashion safari. -

+$10 in Points) $79.99

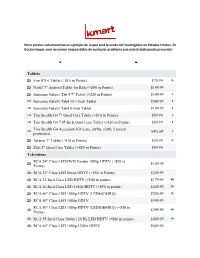

Estos precios solo muestran un ejemplo de lo que será la venta del madrugador en Estados Unidos. En Doctorshoper.com no somos responsables de cualquier problema que este listado pueda presentar. Tablets Fire HD 6 Tablet (+$10 in Points) $79.99 Nabi2 7" Android Tablet for Kids (+$50 in Points) $149.99 Samsung Galaxy Tab 4 7" Tablet (+$20 in Points) $149.99 Samsung Galaxy Tab4 10.1-Inch Tablet $249.99 Samsung Galaxy Tab4 8-Inch Tablet $199.99 Trio Stealth G4 7" Quad Core Tablet (+$10 in Points) $59.99 Trio Stealth G4 7.85-Inch Quad Core Tablet (+$20 in Points) $89.99 Trio Stealth G4 Accessory Kit (case, stylus, cloth, 2 screen 50% off protectors) Xtreme 7" Tablet (+$10 in Points) $39.99 Zeki 8" Quad Core Tablet (+$20 in Points) $89.99 Televisions RCA 24" Class LED/DVD Combo 1080p HDTV (+$20 in $149.99 Points) RCA 32" Class LED Smart HDTV (+$50 in Points) $249.99 RCA 32-Inch Class LED HDTV (+$40 in points) $179.99 RCA 40-Inch Class LED 1080p HDTV (+$50 in points) $249.99 RCA 46" Class LED 1080p HDTV (LED46C45RQ) $299.99 RCA 50" Class LED 1080p HDTV $399.99 RCA 50" Class LED 1080p HDTV (LED50B45RQ) (+$50 in $399.99 Points) RCA 55-Inch Class 1080p 120 Hz LED HDTV (+$60 in points) $499.99 RCA 60" Class LED 1080p 120Hz HDTV $699.99 Sanyo 50-Inch Class LED 1080p HDTV $399.99 Seiki 20" Class LED HDTV (+$20 in Points) $99.99 Seiki 32" Class LED DVD Combo HDTV (SE32HY27-D) (+$20 $179.99 in Points) Seiki 32-Inch Class LED HDTV (+$30 in Points) $169.99 Seiki 40" Class LED 1080p HDTV $239.99 Toshiba 40-Inch Class LED 1080p HDTV (40L1400U) (+$30 in -

Branded Apparel: Market Research Report

+44 20 8123 2220 [email protected] Branded Apparel: Market Research Report https://marketpublishers.com/r/B6F5A10E0D0EN.html Date: September 2010 Pages: 757 Price: US$ 4,500.00 (Single User License) ID: B6F5A10E0D0EN Abstracts This report analyzes the worldwide markets for Branded Apparel in US$ Billion by the following Product Segments: Men's Branded Apparel, Women's Branded Apparel, Children's Branded Apparel, and Sports Branded Apparel. The report provides separate comprehensive analytics for the US, Canada, Japan, Europe, Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Rest of World. Annual estimates and forecasts are provided for each region for the period 2007 through 2015. Also, a seven-year historic analysis is provided for these markets. The report profiles 400 companies including many key and niche players such as Adidas AG, Reebok International Ltd., Arvind Limited, Benetton Group SpA, Ermenegildo Zegna Group, Escada AG, Esprit Europe GmbH, Fruit of the Loom, Inc., Giorgio Armani SpA, Guess?, Inc., HartMarx Corp., Hobo Clothing Company, H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) AB, Inditex, Joe Boxer Company, LLC, Jones Apparel Group, Inc., Levi Strauss & Co., Liz Claiborne, Inc., Naigai Co., Ltd., Nautica Enterprises, Inc., Nike, Inc., Nygård International Ltd., Onward Holdings & Co. Ltd., OshKosh B'Gosh Inc., Oxford Industries Inc., Phillips-Van Heusen Corp., Picadilly Fashions, Raymond Limited, Sanyo Shokai Co., Ltd., The Athletic Sportshow Inc., Tommy Hilfiger U.S.A., Inc., Tribal Sportswear Inc., Triumph Apparel Corporation, Valentino Fashion Group S.p.A., Vanity Fair Corp., and Warnaco Group Inc. Major retailers also discussed in the report include Ann Taylor Stores Corporation, Beall's Department Stores, Inc., Berkshire Hathaway, Charming Shoppes, Inc., Chico’s FAS, Inc., Coldwater Creek, Inc., Gap Inc., Gymboree Corp., J. -

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry

Tracking Corporate Accountability in the Apparel Industry Updated August 3, 2015 COMPANY COUNTRY BANGLADESH ACCORD SIGNATORY FACTORY TRANSPARENCY COMPENSATION FOR TAZREEN FIRE VICTIMS COMPENSATION FOR RANA PLAZA VICTIMS BRANDS PARENT COMPANY NEWS/ACTION Cotton on Group Australia Y Designworks Clothing Company Australia Y Republic, Chino Kids Forever New Australia Y Kathmandu Australia K-Mart Australia Australia Y Licensing Essentials Pty Ltd Australia Y Pacific Brands Australia Y Pretty Girl Fashion Group Pty Australia Y Speciality Fashions Australia Australia Y Target Australia Australia Y The Just Group Australia Woolworths Australia Australia Y Workwear Group Australia Y Fashion Team HandelsgmbH Austria Y Paid some initial relief and C&A Foundation has committed to pay a Linked to Rana Plaza. C&A significant amount of Foundation contributed C&A Belgium Y compensation. $1,000,000 to the Trust Fund. JBC NV Belgium Y Jogilo N.V Belgium Y Malu N.V. Belgium Y Tex Alliance Belgium Y Van Der Erve Belgium Y Brüzer Sportsgear LTD Canada Y Canadian Tire Corporation Ltd Canada Giant Tiger Canada Discloses cities of supplier factories, but not full Anvil, Comfort Colors, Gildan, Gold Toe, Gildan Canada addresses. TM, Secret, Silks, Therapy Plus Contributed an undisclosed amount to the Rana Plaza Trust Hudson’s Bay Company Canada Fund via BRAC USA. IFG Corp. Canada Linked to Rana Plaza. Contributed $3,370,620 to the Loblaw Canada Y Trust Fund. Joe Fresh Lululemon Athletica inc. Canada Bestseller Denmark Y Coop Danmark Denmark Y Dansk Supermarked Denmark Y DK Company Denmark Y FIPO China, FIPOTEX Fashion, FIPOTEX Global, Retailers Europe, FIPO Group Denmark Y Besthouse Europe A/S IC Companys A/S Denmark Y Linked to Rana Plaza. -

Full Clothing Lists.Xlsx

Detailed Clothing List - Alphabetically By Brand Brand Season Item Type Gender Detail 2000 Gymboree N/A Bodysuit Boys Green or red with wheel-shaped zipper pull N/A Pants N/A Fleece pants with cord lock in blue, red, green or gray with gray elastic waistband and "Gymboree" on back pocket 21 Pro USA N/A Hooded Sweatshirts N/A Pullover & zip styles. RN#92952 2b REAL N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Girls Velour, zip front wth "Major Diva" printed on front A.P.C.O. N/A Hooded Sweatshirts N/A Navy or burgundy; "Artic Zone" is printed on front abcDistributing N/A Jacket/Pant Set N/A Fleece, pink or royal blue with waist drawstring; may say "Princess" or "Angel" on it Academy N/A Pajama Pants and Boxers Both Pull-on pants for boys and girls and boxers for girls - see recall for details Active Apparel N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Zipper hooded sweatshirt Adio N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys Zip fleece, white with blue stripes and red panels on sides. Adio on front Aeropostale N/A Hooded jackets/sweatshirts N/A Multiple brands and models - see recall Agean N/A Robes Both Variety of colors; wrap style with waist belt, two front patch pockets and hood Akademiks N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Girls 4 styles - see recall All Over Skaters N/A Hooded Sweatshirts Boys With padlocks, skaters or black with imprint Almar Sales Company N/A Watches N/A Clear plastic watches with white snaps; bands have clear, glitter-filled liquid and colored liquid inside, including pink, blue, red and yellow. -

From Cradle to Cane: the C St of Being a Female C Nsumer

From Cradle to Cane: The C st of Being a Female C nsumer A Study of Gender Pricing in New York City Consumer Affairs Bill de Blasio Julie Menin Mayor Commissioner From Cradle to Cane: The Cost of Being a Female Consumer A Study of Gender Pricing in New York City Bill de Blasio Mayor Julie Menin Commissioner © December 2015. New York City Department of Consumer Affairs. All rights reserved. 2 Acknowledgments The Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) acknowledges the author of this report, Anna Bessendorf, Policy Analyst, and its editor, Shira Gans, Senior Policy Director. DCA would also like to acknowledge the following staff for their contributions: Sandra Abeles, Deputy Chief of Staff; Silvia Alvarez, Acting Associate Commissioner for Communications and Marketing; Amit Bagga, Deputy Commissioner for External Affairs; Yi Seul Chun, Creative Specialist; Debra Halpin, Assistant Commissioner for Creative Services; Eli Jacobs, Senior Analyst, Quality and Data Management; Abigail Lootens, Director of Communications & Marketing; Matthew Petric, Executive Director of Analysis and Strategic Planning; Alba Pico, First Deputy Commissioner; and Carla Van de Walle, Deputy Commissioner for Finance and Administration. DCA also thanks the experts who lent their knowledge to this study: Michael Cone, Managing Partner of FisherBroyles, LLP; Ingrid Johnson, Acting Associate Chairperson for the Home Products Development Department, Fashion Institute of Technology; Dr. Gary Kelm, Professor and Director, James L. Winkle College of Pharmacy, University of Cincinnati; Robin Litwinsky, Chairperson of the Fashion Business Management Department, Fashion Institute of Technology; and Nancy Youman, Co-Director of the Program on Independent Journalism, Open Society Foundations. 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Methodology 5 Findings 5 Impact 6 Detailed Industry Findings 7 I. -

Joe Boxer Last Updated Sunday, 26 April 2020 05:30

Joe Boxer Last Updated Sunday, 26 April 2020 05:30 Joe Boxer Parent Company Iconix Brand Group Category Underwear and related apparel Sector Lifestyle and retail Tagline/ Slogan There is more to life than underwear USP 1 / 4 Joe Boxer Last Updated Sunday, 26 April 2020 05:30 Brand which provides contagious entertaining fun for family and friend STP Segment Primary target is Men expanded into women and kids Target Group Novelty hanging undergarment which identifies the wearer Positioning Change daily SWOT Analysis Strengths 2 / 4 Joe Boxer Last Updated Sunday, 26 April 2020 05:30 1. Brand differentiates the firm from its competitors 2. Continuous improvement on quality to maintain customer loyalty 3. Unique and distinctive product and service for which customer will pay premium 4. Seeking to keep cost lowest to attain advantage over its competitors 5. Very high brand awareness in the American market 6. Sales done through exclusive tie-up with Kmart and Sears stores Weaknesses 1.Needs to ensure sustainable competitive advantage by entering newer markets 2.Other brands have their awareness globally due to variable products differentiation Opportunities 1.Opportunity in emerging market where sales can be increased 3 / 4 Joe Boxer Last Updated Sunday, 26 April 2020 05:30 2. Taking forward the brand image as it has good brand awareness among its target market Threats 1.Emerging new Brands who can offer more innovative products 2.Local undergarment brands which offer lingerie products at less price 3. Fake products and imitations affects brand image Competition Competitors 1.Jockey 2.Calvin Klein 3.Diesel 4 / 4. -

Strategic Analysis of a Small Retail Business

APPROVAL Name: Michele Buttle Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Strategic Analysis Of A Small Retail Business Supervisory Committee: Senior Supervisor Ed Bukszar, Associate Professor Second Reader Michael Parent, Associate Professor Date Approved: ABSTRACT This paper is a strategic analysis of a small silk underwear and sleepwear business. It has been prepared to provide the owner insight into the many factors affecting the industry and her firm's business performance. The analysis is designed to answer two key questions: Should the business continue to operate, and if so how? Could the business be sold? The analysis revealed that, in its current financial state, the company is not an attractive purchase target. Instead, the owner must take immediate steps to achieve, sustain and improve profitability in order to minimize the amount of external financing required and to avoid a distress sale. A niche differentiation strategy combined with a strategic focus on a reduced set of business opportunities is recommended. In addition, sound accounting and financial management practices are required in order to establish an attractive financial track record. DEDICATION To my husband (Michael), my daughter (Charlotte) and extended family for their support and encouragement throughout the MBA program and the writing of this paper. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the owner of the business for her candour and support of this project. I would also like to thank Professor Ed Bukszar for the advice, guidance and interest he provided throughout this project, Professor Alain Duncan for the assistance he provided in restating the firm's financial statements and Professor Michael Parent who acted as my second reader. -

Company Name Brand/Labels It Owns

Apr-16 Company Characteristics May be referred to generically as "Brands" Company Brand/Labels Insert text) Insert ( name it owns Publicly-traded? licensee?University supplier? Municipal past? in Responded Member of MSI? Discloses factories? (if yes, you can find more publicmorefind youcan yes, (if investors) approach and information, providemay support students yes, (If be could FLA and WRC the and involved) inSweatfree cities linkmay yes, to (If database) Communities to openmorebe may yes, (If precedents) haveorresponding,set filecomplaint) ablea beto may yes, (If the to linkfactory the can yes, (If brand) Manufacturer? Framework Global Agreement? (If yes, the brand has more control control more has brand the yes, (If overfactory) the Abercrombie & Fitch Abercrombie & Fitch abercrombie kids Hollister Adidas Group Adidas Adidas Golf Reebok FLA Rockport Taylor Made Aeropostale Aeropostale American Eagle Outfitters American Eagle Outfitters Aerie Bennetton C&A C&A Yessica Yessica pure Your Sixth sense Angelo Litrico Westbury Canda Clockhouse Baby Club Palomino Here & There Rodeo Sport Carter’s Inc Carter's Child of Mine Genuine Kids Just One You Oshkosh B’Gosh Precious Firsts Cintas Cintas Columbia Sportswear Columbia Sportswear Pacific Trail FLA* Sorel Dallas Cowboys / Silver Star Dallas Cowboys FLA Trojans Delta Delta Activewear Intensity FLA Soffee Soffee Chic Devanlay Lacoste Disney Personajes de caricaturas de Disney Disney [The Walt Disney Captain America Company] Spiderman Star Wars Toy Story B.V.D. Fruit -

Y Farmacia $54 88 $2 88 $2 99 $7 88 $289 88

Y FARMACIA OFERTAS VÁLIDAS DESDE EL DOMINGO 24 DE AGOSTO HASTA EL SÁBADO 30 DE AGOSTO, 2014 % precios más bajos desc. de la 40 VENTA 9.88 Venta 4.49-26.99 temporada reg. 7.49-44.99 TODA LA ROPA TODO EL CALZADO BONGO® Y DREAM BONGO® Y ROUTE 66® OUT LOUD® PARA PARA DAMAS EN VENTA VENTA 5.88-29.88 VENTA 9.88 DAMAS Y ROUTE 66® reg. 7.99-34.99 PARA CABALLEROS. Excluye sandalias. precio precio precios s más bajo más bajo os de la de la más bajos temporada temporada de la ada $ temporada 2por 7 reg. 4.99-5.99.999 $ 88 VENTA Pqte. de 3-pr. de 7 pr. medias Joe Boxer® para reg. 9.99-14.99 damas, caballeros, niños VENTA Calzado para y niñas. el regreso a clases Ahorra 20% en todas las otras para niños y niñas. medias, venta 1.59-11.99, Estilos ilustrados. reg. 1.99-14.99. AHORRA 20% EN TODOS LOS AHORRA 30% EN TODOS LOSS OTROS MICROONDAS OTROS MUEBLES Venta 54.39-135.59, reg. 67.99-169.49 Venta 13.29-352.79, reg. 18.99-503.99 precio precio más bajo más bajo de la de la $ 88 temporada $ 88 $ 88 $ 99 temporada 2 c.u. 54 289 jgo. 2c.u. reg. 4.69 reg.r 84.99 reg. 503.99 reg. 5.89 VENTA Toallas de baño VENTA Microondas Oster VENTA Jgo. de comedor Essential VENTA Almohada Joe Essential Home®. de .7’-cú. en acero inoxidable. Home® de 7-pzs. Incluye mesa Boxer® Sweet Dreamer 100% algodón.