1 “The Man with the Midas Touch”: the Haptic Geographies of James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Bond a 50 The

JAMES BOND: SIGNIFYING CHANGING IDENTITY THROUGH THE COLD WAR AND BEYOND By Christina A. Clopton Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts Supervisor: Professor Alexander Astrov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Word Count: 12,928 Abstract The Constructivist paradigm of International Relations (IR) theory has provided for an ‘aesthetic turn’ in IR. This turn can be applied to popular culture in order to theorize about the international system. Using the case study of the James Bond film series, this paper investigates the continuing relevancy of the espionage series through the Cold War and beyond in order to reveal new information about the nature of the international political system. Using the concept of the ‘empty signifier,’ this work establishes the shifting identity of James Bond in relation to four thematic icons in the films: the villains, locations, women and technology and their relation to the international political setting over the last 50 years of the films. Bond’s changing identity throughout the series reveals an increasingly globalized society that gives prominence to David Chandler’s theory about ‘empire in denial,’ in which Western states are ever more reluctant to take responsibility for their intervention abroad. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Alexander Astrov for taking a chance with me on this project and guiding me through this difficult process. I would also like to acknowledge the constant support and encouragement from my IRES colleagues through the last year. -

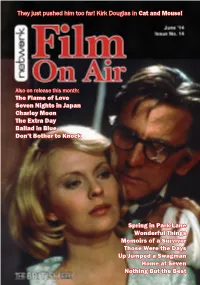

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

The Hero with Mad Skills James Bond and the World of Extreme Sports

The Hero with Mad Skills James Bond and the World of Extreme Sports DAVID M. PEGRAM In the 2007 Matchstick Productions film, Seven Sunny Days, professional skier and BASE jumper Shane McConke created a near shot!" -shot remake of the #ames Bond ski chase from The Spy Who Loved Me $%&77'( )he original featured stuntman +ick S l,ester $as #ames Bond' skiin* off the top of Mount Asgard, in Canada, to -hat appears to "e certain death( But, in the midst of freefall, S l,ester kicks off his skis and then opens a .nion #ack parachute, in -hat has become one of the /most iconic” scenes in the cinematic histor of #ames Bond $Aja Cho-dhur 1td( in Murph 20%2'( In Seven Sunny Days, McConke 3s jump is more darin*( As he flies off the ed*e of the cliff $shot in 4or-a , rather than Canada', he completes three full somersaults in midair before deplo in* his chute, in a demonstration of ho- far e5treme sports had come in the thirt ears since the S l,ester3s jump( )he recreation of S l,ester3s stunt -as McConke 3s homage to the cinematic moment that inspired him the most6 /)hat -as the coolest stunt I3d e,er seen,0 he recalled, creditin* S l,ester3s jump for *i,in* him the idea to sk di,e and BASE jump in the first place $McConkey 20%2'( )hat a #ames Bond film should ha,e such an influence on a skiin* /legend0 $Ble,ins 200&' su**ests, perhaps, a si*nificant connection "et-een the Bond franchise and the -orld of extreme sports. -

Die Figur Des Antagonisten in Den James Bond-Filmen - Film- Und Zeitgeschichtliche Kontexte Eines Öffentlichen Feindbildes"

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit "Die Figur des Antagonisten in den James Bond-Filmen - Film- und zeitgeschichtliche Kontexte eines öffentlichen Feindbildes" Verfasserin Daniela Müller angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. habil Ramón Reichert Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Wien, am Unterschrift: 2 Danksagung Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinem Betreuer Prof. Ramón Reichert, der mich während des Schreibens meiner Diplomarbeit gut betreut hat, indem er mich über den "Tellerrand" hinausblicken hat lassen und mich immer wieder motiviert hat. Weiters gab er mir die Möglichkeit über ein Thema zu schreiben, welches mir immer schon am Herzen lag. Ein weiterer und besonders großer Dank gilt meinen Eltern, die es mir ermöglicht haben, meine Leidenschaft zu studieren - Theater und Film. Besonders meine Mama, Eva Müller, möchte ich hervorheben, die meine komplette Arbeit gelesen und mir immer wieder neue mögliche Ansätze aufgezeigt hat. Auch meinen Freunden soll an dieser Stelle gedankt werden, die mich immer wieder motiviert und mit Interesse meine Arbeit verfolgt haben. Last but definitely not least, danke ich von ganzem Herzen meiner besten Freundin, Eszter Anghi, fürs Korrekturlesen. 3 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung S. 7 2. Zur Entstehung der Bond-Romane S. -

Spectre, Connoting a Denied That This Was a Reference to the Earlier Films

Key Terms and Consider INTERTEXTUALITY Consider NARRATIVE conventions The white tuxedo intertextually references earlier Bond Behind Bond, image of a man wearing a skeleton mask and films (previous Bonds, including Roger Moore, have worn bone design on his jacket. Skeleton has connotations of Central image, protag- the white tuxedo, however this poster specifically refer- death and danger and the mask is covering up someone’s onist, hero, villain, title, ences Sean Connery in Goldfinger), providing a sense of identity, someone who wishes to remain hidden, someone star appeal, credit block, familiarity, nostalgia and pleasure to fans who recognise lurking in the shadows. It is quite easy to guess that this char- frame, enigma codes, the link. acter would be Propp’s villain and his mask that is reminis- signify, Long shot, facial Bond films have often deliberately referenced earlier films cent of such holidays as Halloween or Day of the Dead means expression, body lan- in the franchise, for example the ‘Bond girl’ emerging he is Bond’s antagonist and no doubt wants to kill him. This guage, colour, enigma from the sea (Ursula Andress in Dr No and Halle Berry in acts as an enigma code for theaudience as we want to find codes. Die Another Day). Daniel Craig also emerged from the sea out who this character is and why he wants Bond. The skele- in Casino Royale, his first outing as Bond, however it was ton also references the title of the film, Spectre, connoting a denied that this was a reference to the earlier films. ghostly, haunting presence from Bond’s past. -

John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry

John Barry - Great Movie Sounds of John Barry - The Audio Beat - www.TheAudioBeat.Com 29.10.18, 1431 Music Reviews John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry Columbia/Speakers Corner S BPG 62402 180-gram LP 1963 & 1966/2018 Music Sound by Guy Lemcoe | October 26, 2018 uring his fifty-year career, composer John Barry won five Oscars and four Grammys. Among the scores he produced is my favorite, and what I consider his magnum opus, Dances with Wolves. Barry's music is characterized by bombast tempered with richly harmonious, "loungey," often sensuous melodies. Added to those are dramatic accents of brass, catchy Latin rhythms and creative use of flute, harp, timpani and exotic percussion (such as the talking drums, which feature prominently in the score from Born Free). The Kentonesque brass writing (trumpets reaching for the sky and bass trombones plumbing the lower registers), which helps define the Bond sound, no doubt stems from Barry’s studies with Stan Kenton arranger Bill Russo. I also hear traces of Max Steiner and Bernard Hermann in Barry's scores. When he used vocals, the songs often became Billboard hits. Witness Shirley Bassey’s work on Goldfinger, Tom Jones’s Thunderball, Matt Monro’s From Russia With Love and Born Free, Nancy Sinatra’s You Only Live Twice and Louis Armstrong’s On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Side one of Great Movie Sounds of John Barry features a half-dozen Bond-film flag-wavers -- two each from Thunderball and From Russia With Love and one each from Goldfinger and Dr. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

An Elegy to My Lord Hampstershire a View to a Kill (1985), Directed By

An Elegy to My Lord Hampstershire A View to a Kill (1985), Directed by John Glen By Christina Harlin, your Fearless Young Orphan For my friend Max, who convinced me to give it a try. I know Roger Moore did more with his career than simply play James Bond. Nevertheless, one of the Bonds is who he’ll always be to me. Well, I admit, that’s really all I’ve seen him do, and in his own way, he did it perfectly well. He was lucky enough to be directed by both John Glen and Guy Hamilton in multiple Bond films. Roger Moore’s era as Bond produced some fine espionage movies– and some unforgettably silly ones – and, the thing about Bond movies is, those two things are not mutually exclusive. Especially not with Lord Hampstershire on board. I don’t want to get into a debate with myself (I am my most formidable debating opponent, impossible to argue with) about “who’s the better Bond” because to my mind, every Bond actor has managed to hit the right notes at some point (even the awful interpretation of Pierce Brosnan managed to impress once or twice). Remember (poor kids, how could you forget?) that I subscribe to the cipher-agent theory and think of Bond as only a professional title, so that despite some (lame!) evidence to the contrary, none of these guys are actually playing the same character. Roger Moore’s take on the playboy spy really emphasized the “playboy” and downplayed the “spy,” and for about half the time he was at the helm, he was intentionally playing the part for comedy. -

Download 007Museum Map

NEWS! at the Bond Museum The aircraft Cessna 172 VIBRA.SE • 17-7019 JAMES BOND 007 James Bond Museum Emmabodavägen 20 Nybro A full-sized Gondola from Venice (apparently just like the one that Roger Moore used in Moonraker). Stockholm MUSEUM Göteborg Växjö Nybro Kalmar Malmö JAMES BOND Emmabodavägen Väg 25 mot Växjö väg Jutarnas MUSEUM EMMABODAVÄGEN 20, 382 45 NYBRO SWEDEN 0 4 81–129 6 0 Västra Förbifarten WWW.007MUSEUM.COM Väg 25 mot Kalmar GPS COORDIN AT ES: N56° 44.416 • E015° 53.462 NYBRO • SWEDEN Golden gun BMW 1200 Cruiser Motorcycle Golden gun pistol SonyTelephones Ericsson P800, K600i BMW motorbike ”The”The Man Man With withThe Golden the Gun” ”Tomorrow Never Dies” Sony Ericsson Golden gun” JamesCinema Bond chair Premierecinema 1 Special designedDesigned glassware glass Casino,Casino Roulette elcome to The World’s only James Bond BondcarsBond cars IanThe Fleming writer the writer Designed007 designed glassware, 007glass Ian Fleming 007 Museum, located in Nybro Sweden. WOver 1,000 square meter. James Bond Collection started in 1965 after Gold- finger by Gunnar Schäfer (change name 2007 to James Bond). The Bond 007 museum is a tribute to Ian Fleming and my missing father Johannes Schäfer, lost since 1959. James Bond 007 Museum started in Nybro Sweden 2002. Book ”Goldfinger”Book ”Goldfinger” GeoffreyGeoffrey Boothroyd Boothroyd and PinballPinball ”Golden ”Golden Eye” Eye” and Ian FlemingsIan Fleming letter letter We have a full-sized Gondola from Venice (apparently just like the one that Roger Moore used in Moonraker). You can see Aston Martin, Airplane Cessna 172, Glastron Boat, BMW Z3, Snowmobile, BMW motorbike, Jaguar E-Type. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

1 Dr. No, 1962 #2 from Russia with Love, 1963

1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess Search Site: Search Follow usus on on Twitter Like usus on on Facebook Lists Top 10s Characters Cast Gadgets Movies Quotes More List of All James Bond Movies The complete list of official James Bond films, made by EON Productions. Beginning with Sean Connery, and going through George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig. Have you ever wondered how many James Bond movies there are? The new film, Spectre, will be released October 2015. #1 Dr. No, 1962 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Honey Ryder Director: Terence Young Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: Dr. No was the first 007 film produced by EON Productions. Bond is sent to Jamaica to investigate the death of MI6 agent John Strangways. He finds his way to Crab Key island, where the mysterious Dr. No awaits. ##22 From Russia With Love, 1963 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Tatiana Romanova Director: Terence Young Running Time: 115 Minutes Synopsis: When MI6 gets a chance to get their hands on a Lektor decoder, Bond is sent to Turkey to seduce the beautiful Tatiana, and bring back the machine. With the help of Kerim Bey, Bond escapes on the Orient Express, but might not make it off alive. hhttttpp::////wwwwww..000077jjaammeess..ccoomm//aarrttiicclleess//lliisstt__ooff__jjaammeess__bboonndd__mmoovviieess..pphhpp 11//44 1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess #3 Goldfinger, 1964 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Pussy Galore Director: Guy Hamilton Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: The Bank of England has detected an unauthorized leakage of gold from the country, and Bond is sent to investigate.