Professional Paper SJ98-PP1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Publication SJ92-SP16 LAKE JESSUP RESTORATION

Special Publication SJ92-SP16 LAKE JESSUP RESTORATION DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION HATER BUDGET AND NUTRIENT BUDGET Prepared for: ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT P.O. Box 1429 Palatka, Florida Prepared By: Douglas H. Keesecker HATER AND AIR RESEARCH, INC. Gainesville, Florida May 1992 File: 91-5057 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Page 1 of 2) Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 PURPOSE 1-1 1.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA 1-2 2.0 DATA COMPILATION 2-1 2.1 HISTORICAL DATA 2-1 2.1.1 Previous Studies 2-1 2.1.2 Climatoloqic Data 2-3 2.1.3 Hydrologic Data 2-4 2.1.4 Land Use and Cover Data 2-6 2.1.5 On-site Sewage Disposal System (OSDS) Data 2-8 2.1.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP1 Data 2-9 2.1.7 Surface Water Quality Data . 2-10 3.0 WATER BUDGET 3-1 3.1 METHODOLOGY 3-1 3.1.1 Springflow and Upward Leakage 3-2 3.1.2 Direct Precipitation 3-4 3.1.3 Land Surface Runoff 3-4 3.1.4 Shallow Groundwater Inflow 3-6 3.1.5 Septic Tank (OSDS1 Inflows 3-7 3.1.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent 3-8 3.1.7 Surface Evaporation 3-8 3.1.8 Surface Water Outflows 3-9 3.2 RESULTS - WATER BUDGET 3-10 3.3 DISCUSSION 3-16 3.4 ESTIMATE OF ERROR 3-18 3.4.1 Sprinoflow and Upward Leakage 3-18 3.4.2 Direct Precipitation 3-19 3.4.3 Land Surface Runoff 3-19 3.4.4 Shallow Groundwater Inflow 3-20 3.4.5 Septic Tank (OSDS1 Inflows 3-21 3.4.6 Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent 3-22 3.4.7 Surface Evaporation 3-22 3.4.8 Surface Water Outflows 3-22 LAKE JESSUP[WP]TOC 052192 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Page 2 of 2) Section Page 4.0 NUTRIENT BUDGETS 4-1 4.1 METHODOLOGY 4-1 4.1.1 Direct Precipitation Loading 4-2 4.1.2 Land Surface Runoff Loading 4-3 4.1.3 Shallow Groundwater Inflow Loading 4-3 4.1.4 Septic Tank Loading 4-4 4.1.5 Wastewater Treatment Plant Loading 4-4 4.1.6 St. -

Final Summary Document of Public Scoping Comments Submitted by the 3/31/11 Deadline

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Proposed Everglades Headwaters National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area Summary of Public Scoping Comments - as of 3.31.2011 Comments were submitted in a variety of ways (e.g., at a public scoping meeting and by mail, fax, and email). Attendance at the public scoping meetings averaged ~440 per meeting: ~200 in Sebring, ~325 in Kissimmee, ~665 in Okeechobee, and ~580 in Vero Beach. As of March 31, 2011, the deadline for public scoping comments, over 38,000 written comments had been received. The comments were summarized and are grouped together by topic, as listed. • Wildlife and Habitat • Resource Protection • Recreation • Administration • General/Other Comments List of acronyms used in comments: BLM Bureau of Land Management CERP Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan DEP Florida Department of Environmental Protection DOI U.S. Department of Interior DOT Florida Department of Transportation EH Everglades Headwaters ESV Ecosystem Services Values FDOT Florida Department of Transportation FWC Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission FWS U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, also USFWS LOPP Lake Okeechobee Protection Plan NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NPS National Park Service NRC National Research Council NWR National Wildlife Refuge PES Payments for Ecosystem Services SFWMD South Florida Water Management District STA Stormwater Treatment Area TEV Total Economic Value TNC The Nature Conservancy USFWS U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, also FWS Wildlife and Habitat General • If worried about the environment, we had more endangered species than anywhere in the State. We have the same amount of endangered species. We are good land stewards, so we don’t need the government or anything else. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

William Selby Harney: Indian Fighter by OLIVER GRISWOLD We Are Going to Travel-In Our Imaginations-A South Florida Route with a Vivid Personality

William Selby Harney: Indian Fighter By OLIVER GRISWOLD We are going to travel-in our imaginations-a South Florida route with a vivid personality. We are going back-in our imaginations-over a bloody trail. We are going on a dramatic military assignment. From Cape Florida on Key Biscayne, we start on the morning of De- cember 4, 1840. We cross the sparkling waters of Biscayne Bay to within a stone's throw of this McAllister Hotel where we are meeting. We are going up the Miami River in the days when there was no City of Miami. All our imaginations have to do is remove all the hotels from the north bank of the Miami River just above the Brickell Avenue bridge- then in the clearing rebuild a little military post that stood there more than a hundred years ago. At this tiny cluster of stone buildings called Ft. Dallas, our expedition pauses for farewells. We are going on up to the headwaters of the Miami River-and beyond-where no white man has ever been before. The first rays of the sun shed a ruddy light on a party of 90 picked U.S. soldiers. They are in long dugout canoes. The sunrise shines with particular emphasis on the fiery-red hair of a tall officer. It is as if the gleaming wand of destiny has reached down from the Florida skies this morning to put a special blessing on his perilous mission. He commands the flotilla to shove off. But before we join him on his quest for a certain villainous redskin, let us consider who this officer is. -

Historical Rates of Sediment and Nutrient Accumulation in Marshes of the Upper St

Journal of Paleolimnology 26: 241–257, 2001. 241 © 2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Historical rates of sediment and nutrient accumulation in marshes of the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA Mark Brenner1, Claire L. Schelske2 & Lawrence W. Keenan3 1Department of Geological Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 2Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, University of Florida, 7922 NW 71st Street, Gainesville, FL 32653, USA 3St. Johns River Water Management District, P.O. Box 1429, Palatka, FL 32178, USA Received 26 May 2000; accepted 13 September 2000 Key words: accumulation rates, Florida, 210Pb dating, nutrients, paleolimnology, sediment, wetlands Abstract We used 210Pb-dated sediment cores from wetlands and Blue Cypress Lake, in the Upper St. Johns River Basin (USJRB), Florida, USA, to measure historical accumulation rates of bulk sediment, total carbon (C), total nitrogen (N), and total phosphorus (P). Marsh cores displayed similar stratigraphies with respect to physical properties and nutrient content. Wetland sediments typically contained > 900 mg organic matter (OM) g–1 dry mass, > 500 mg C g–1, and 30–40 mg N g–1. OM, C, and N concentrations were slightly lower in uppermost sediments of most cores, but displayed no strong stratigraphic trends. Total P concentrations were relatively low in bottommost deposits (0.01– 0.11 mg g–1), but ranged from 0.38–2.67 mg g–1 in surface sediments. The mean sediment accretion rate in the marsh since ~ 1900, 0.33 ± 0.05 cm yr–1, was calculated from ten 210Pb-dated cores. All sites displayed increases in accu- mulation rates of bulk sediment, C, N, and P since the early part of the 20th century. -

Appendix 1 U.S

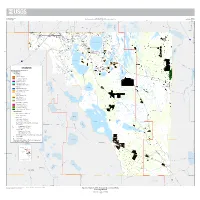

U.S. Department of the Interior Prepared in cooperation with the Appendix 1 U.S. Geological Survey Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Office of Agricultural Water Policy Open-File Report 2014−1257 81°45' 81°30' 81°15' 81°00' 80°45' 524 Jim Creek 1 Lake Hart 501 520 LAKE 17 ORANGE 417 Lake Mary Jane Saint Johns River 192 Boggy Creek 535 Shingle Creek 519 429 Lake Preston 95 17 East Lake Tohopekaliga Saint Johns River 17 Reedy Creek 28°15' Lake Lizzie Lake Winder Saint Cloud Canal ! Lake Tohopekaliga Alligator Lake 4 Saint Johns River EXPLANATION Big Bend Swamp Brick Lake Generalized land use classifications 17 for study purposes: Crabgrass Creek Land irrigated Lake Russell Lake Mattie Lake Gentry Row crops Lake Washington Peppers−184 acresLake Lowery Lake Marion Creek 192 Potatoes−3,322 acres 27 Lake Van Cantaloupes−633 acres BREVARD Lake Alfred Eggplant−151 acres All others−57 acres Lake Henry ! UnverifiedLake Haines crops−33 acres Lake Marion Saint Johns River Jane Green Creek LakeFruit Rochelle crops Cypress Lake Blueberries−41 acres Citrus groves−10,861 acres OSCEOLA Peaches−67 acresLake Fannie Lake Hamilton Field Crops Saint Johns River Field corn−292 acres Hay−234 acres Lake Hatchineha Rye grass−477 acres Lake Howard Lake 17 Seeds−619 acres 28°00' Ornamentals and grasses Ornamentals−240 acres Tree nurseries−27 acres Lake Annie Sod farms−5,643Lake Eloise acres 17 Pasture (improved)−4,575 acres Catfish Creek Land not irrigated Abandoned groves−4,916 acres Pasture−259,823 acres Lake Rosalie Water source Groundwater−18,351 acres POLK Surface water−9,106 acres Lake Kissimmee Lake Jackson Water Management Districts irrigated land totals Weohyakapka Creek Tiger Lake South Florida Groundwater−18,351 acres 441 Surface water−7,596 acres Lake Marian St. -

Status of the Aquatic Plant Maintenance Program in Florida Public Waters

Status of the Aquatic Plant Maintenance Program in Florida Public Waters Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2006 - 2007 Executive Summary This report was prepared in accordance with §369.22 (7), Florida Statutes, to provide an annual assessment of the control achieved and funding necessary to manage nonindigenous aquatic plants in intercounty waters. The authority of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) as addressed in §369.20 (5), Florida Statutes, extends to the management of nuisance populations of all aquatic plants, both indigenous and nonindigenous, and in all waters accessible to the general public. The aquatic plant management program in Florida’s public waters involves complex operational and financial interactions between state, federal and local governments as well as private sector compa- nies. A summary of plant acres controlled in sovereignty public waters and associated expenditures contracted or monitored by the DEP during Fiscal Year 2006-2007 is presented in the tables on page 42 of this report. Florida’s aquatic plant management program mission is to reduce negative impacts from invasive nonindigenous plants like water hyacinth, water lettuce and hydrilla to conserve the multiple uses and functions of public lakes and rivers. Invasive plants infest 95 percent of the 437 public waters inventoried in 2007 that comprise 1.25 million acres of fresh water where fishing alone is valued at more than $1.5 billion annually. Once established, eradicating invasive plants is difficult or impossible and very expensive; therefore, continuous maintenance is critical to sustaining navigation, flood control and recreation while conserving native plant habitat on sovereignty state lands at the lowest feasible cost. -

2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida: Sections 303(D), 305(B), and 314 Report and Listing Update

2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida: Sections 303(d), 305(b), and 314 Report and Listing Update Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration Florida Department of Environmental Protection June 2020 2600 Blair Stone Rd. Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 floridadep.gov 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida, June 2020 This Page Intentionally Blank. Page 2 of 160 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida, June 2020 Letter to Floridians Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Bob Martinez Center Noah Valenstein 2600 Blair Stone Road Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400 June 16, 2020 Dear Floridians: It is with great pleasure that we present to you the 2020 Integrated Water Quality Assessment for Florida. This report meets the Federal Clean Water Act reporting requirements; more importantly, it presents a comprehensive analysis of the quality of our waters. This report would not be possible without the monitoring efforts of organizations throughout the state, including state and local governments, universities, and volunteer groups who agree that our waters are a central part of our state’s culture, heritage, and way of life. In Florida, monitoring efforts at all levels result in substantially more monitoring stations and water quality data than most other states in the nation. These water quality data are used annually for the assessment of waterbody health by means of a comprehensive approach. Hundreds of assessments of individual waterbodies are conducted each year. Additionally, as part of this report, a statewide water quality condition is presented using an unbiased random monitoring design. These efforts allow us to understand the state’s water conditions, make decisions that further enhance our waterways, and focus our efforts on addressing problems. -

Technical Publication Sj 87-3 Establishment of Minimum Surface Water Requirements for the Greater Lake Washington Basin

TECHNICAL PUBLICATION SJ 87-3 ESTABLISHMENT OF MINIMUM SURFACE WATER REQUIREMENTS FOR THE GREATER LAKE WASHINGTON BASIN BY G. B. Hall Division of Environmental Sciences Department of Water Resources St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, Florida February, 1987 Project No. 20 024 24 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Brad Purcell provided assistance in graphics; Marvin Williams, Chris Mayberry and Palmer Kinser assisted in the analysis of aerial photography and the digitization and plotting of maps; and Phyllis Howard and Sherry Dearth typed the report. Drafts of the manuscript were critically read by Barbara Vergara, Edgar Lowe, Charles Tai, Don Rao, and Robert Massarelli (SBWA, Melbourne). ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i i LIST OF FIGURES V LIST OF TABLES viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 5 Background and Scope 5 The S tudy Area 9 Land-Use and Regional Importance 9 Soils 11 Climate 14 Ecological Alteration of the Floodplain 18 Surface Water Hydrology 25 METHODOLOGY 33 Environmental Analyses and Minimum Level Criteria Development 33 Basin Morphometry 33 Floodplain Vegetation 34 Minimum Level Criteria Development 36 RESULTS 40 Floodplain Alteration 40 Basin Morphometry 40 Floodplain Vegetation 40 Minimum Level Criteria 49 Floodplain Vegetation and Soils 49 Water Quality 54 Transfer of Detrital Materials and Sediments 63 Fish and Wildlife Habitat 64 Recreation and Navigation 65 Aesthetic and Scenic Attributes 66 DISCUSSION 67 LITERATURE CITED 72 APPENDIX A APPENDIX B IV LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE PAGE 1 Map of the Upper St. Johns River Basin showing the study area 7 2 Map of the Greater Lake Washington Basin, 3 Soils of the Upper St. -

The Breeding Range of the Black-Necked Stilt

248 The Wilson Bulletin-December, 1929 foot a constant reminder of the disagreeable experience. It is probable that hunger and the memory of source of sustenance are respectively stronger and more accurate in this muscular, bold creature than any recollection of pain or inconvenience which may have been caused at or near the source of food supply.- GEORGE MIKSCH SUTTON, Game Commission, Harrisburg, Pa. The Breeding Range of the Black-necked Stilt.-The breeding range of the Black-necked Stilt (Ilimantopus mexicanus) has been steadily increasing throughout different parts of southern and central Florida during the last few years. Where it was not found at all a few years ago it now breeds. In 1909 I found these birds nesting at Kissimmee and also at Lake Kissimmce on Rabbit Island. In 1915 they bred in numbers at Lake Harney, Seminole County. These places are still used as breeding places to the present date, May, 1929. They breed at Marco Island, some of the Keys. Puzzle Lake, Seminole County, Mer- ritts’ Island, along the St. Johns’ River between Sanford and Lake Harney, and at Geneva Ferry. The latest places discovered were at Turkey Hammock, Osceola County, which is where the Kissimee River begins at the south end of Lake Kissimee. About a dozen pairs were found evidently breeding, judging from their behavior, by Messrs. Arthur H. Howell and W. H. Ball, and me, on May 12, 1929. We also found four breeding pairs at Alligator RlufI, which is along the Kissimee River, on May 11, 7929. In March, 1908, March, 1910, and in 1912, I had covered this same territory and failed to see Rlack-necked Stilts in these two places. -

Your Guide to Eating Fish Caught in Florida

Fish Consumption Advisories are published periodically by the Your Guide State of Florida to alert consumers about the possibility of chemically contaminated fish in Florida waters. To Eating The advisories are meant to inform the public of potential health risks of specific fish species from specific Fish Caught water bodies. In Florida February 2019 Florida Department of Health Prepared in cooperation with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and Agriculture and Consumer Services, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 2019 Florida Fish Advisories • Table 1: Eating Guidelines for Fresh Water Fish from Florida Waters (based on mercury levels) page 1-50 • Table 2: Eating Guidelines for Marine and Estuarine Fish from Florida Waters (based on mercury levels) page 51-52 • Table 3: Eating Guidelines for species from Florida Waters with Heavy Metals (other than mercury), Dioxin, Pesticides, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), or Saxitoxin Contamination page 53-54 Eating Fish is an important part of a healthy diet. Rich in vitamins and low in fat, fish contains protein we need for strong bodies. It is also an excellent source of nutrition for proper growth and development. In fact, the American Heart Association recommends that you eat two meals of fish or seafood every week. At the same time, most Florida seafood has low to medium levels of mercury. Depending on the age of the fish, the type of fish, and the condition of the water the fish lives in, the levels of mercury found in fish are different. While mercury in rivers, creeks, ponds, and lakes can build up in some fish to levels that can be harmful, most fish caught in Florida can be eaten without harm. -

Annual Report of Activities Conducted Under the Cooperative Aquatic Plant Control Program in Florida Public Waters for Fiscal Year 2012-2013

Annual Report of Activities Conducted under the Cooperative Aquatic Plant Control Program in Florida Public Waters for Fiscal Year 2012-2013 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Invasive Plant Management Section Submitted by: FL Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Invasive Plant Management Section 3900 Commonwealth Blvd. MS705 Tallahassee, FL 32399 Phone: 850-617-9420 Fax: 850-922-1249 Annual Report of Activities Conducted under the Cooperative Aquatic Plant Control Program in Florida Public Waters for Fiscal Year 2012-2013 This report was prepared in accordance with §369.22 (7), Florida Statutes, to provide an annual summary of plants treated and funding necessary to manage aquatic plants in public waters. The Cooperative Aquatic Plant Control Program administered by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) in Florida’s public waters involves complex operational and financial interactions between state, federal and local governments as well as private sector companies. FWC’s aquatic plant management program mission is to reduce negative impacts from invasive nonindigenous plants like water hyacinth, water lettuce and hydrilla to conserve the multiple uses and functions of public lakes and rivers. Invasive plants infest 96% of Florida’s 451 public waters inventoried in 2013 that comprise 1.26 million acres of fresh water. Once established, eradicating invasive plants is difficult or impossible and very expensive; therefore, continuous maintenance is critical to keep invasive plants at low levels to