Analysis of Law in the EU Pertaining to Cross-Border Disaster Relief (EU IDRL Study) Country Report by the French Red Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Implodes and Workers Explode in Flanders, 1789-1914

................................................................. CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 . --------- ---- --------------- --- ....................... - ---------- CRSO Working Paper [I296 Copies available through: Center for Research on Social Organization University of Michigan 330 Packard Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 CAPITAL IMPLODES AND WORKERS EXPLODE IN FLANDERS, 1789-1914 Charles Tilly University of Michigan July 1983 Flanders in 1789 In Lille, on 23 July 1789, the Marechaussee of Flanders interrogated Charles Louis Monique. Monique, a threadmaker and native of Tournai, lived in the lodging house kept by M. Paul. Asked what he had done on the night of 21-22 July, Monique replied that he had spent the night in his lodging house and I' . around 4:30 A.M. he got up and left his room to go to work. Going through the rue des Malades . he saw a lot of tumult around the house of Mr. Martel. People were throwing all the furniture and goods out the window." . Asked where he got the eleven gold -louis, the other money, and the elegant walking stick he was carrying when arrested, he claimed to have found them all on the street, among M. Martel's effects. The police didn't believe his claims. They had him tried immediately, and hanged him the same day (A.M. Lille 14336, 18040). According to the account of that tumultuous night authorized by the Magistracy (city council) of Lille on 8 August, anonymous letters had warned that there would be trouble on 22 July. On the 21st, two members of the Magistracy went to see the comte de Boistelle, provincial military commander; they proposed to form a civic militia. -

Space Applications for Civil Protection

Space Applications for Civil Protection A Roadmap for Civil Protection with Particular Interest to SatCom as Contribution to the Polish EU Council Presidency in 2011 Report 37 September 2011 Erich Klock Mildred Trögeler Short title: ESPI Report 37 ISSN: 2076-6688 Published in September 2011 Price: €11 Editor and publisher: European Space Policy Institute, ESPI Schwarzenbergplatz 6 • 1030 Vienna • Austria http://www.espi.or.at Tel. +43 1 7181118-0; Fax -99 Rights reserved – No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose with- out permission from ESPI. Citations and extracts to be published by other means are subject to mentioning “Source: ESPI Report 37; September 2011. All rights reserved” and sample transmission to ESPI before pub- lishing. ESPI is not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, product liability or otherwise) whether they may be direct or indirect, special, inciden- tal or consequential, resulting from the information contained in this publication. Design: Panthera.cc ESPI Report 37 2 September 2011 Space Applications for Civil Protection Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 9 2. Previous User-Driven Activities Initiated by ESA 11 2.1 ESA Short Term Action Plan 11 2.2 ESA Proposal for a Satellite Communication Programme in Support of Civil Protection 12 2.3 CiProS Project 14 2.4 IP-based Services via Satellite for Civil Protection 16 2.5 The “Decision” Project: Multinational Telecoms Adapter 17 2.6 Multinational Pan European Satellite Telecommunication Adapter 19 3. -

Devotion and Development: ∗ Religiosity, Education, and Economic Progress in 19Th-Century France

Devotion and Development: ∗ Religiosity, Education, and Economic Progress in 19th-Century France Mara P. Squicciarini Bocconi University Abstract This paper uses a historical setting to study when religion can be a barrier to the diffusion of knowledge and economic development, and through which mechanism. I focus on 19th-century Catholicism and analyze a crucial phase of modern economic growth, the Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914) in France. In this period, technology became skill-intensive, leading to the introduction of technical education in primary schools. At the same time, the Catholic Church was promoting a particularly anti-scientific program and opposed the adoption of a technical curriculum. Using data collected from primary and secondary sources, I exploit preexisting variation in the intensity of Catholicism (i.e., religiosity) among French districts. I show that, despite a stable spatial distribution of religiosity over time, the more religious districts had lower economic development only during the Second Industrial Revolution, but not before. Schooling appears to be the key mechanism: more religious areas saw a slower introduction of the technical curriculum and instead a push for religious education. Religious education, in turn, was negatively associated with industrial development about 10-15 years later, when school-aged children would enter the labor market, and this negative relationship was more pronounced in skill-intensive industrial sectors. JEL: J24, N13, O14, Z12 Keywords: Human Capital, Religiosity, -

LA CARTE Du Vignoble

ALBAS (C2) VIGNOBLES MAUROUX (A2) PRAYSSAC (C2) PUY-L’ÉVÊQUE (C2) SAINT-VINCENT-RIVE-D’OLT (D2) TRESPOUX-RASSIELS (E3) VILLESÈQUE (D3) 102 33 81 31 141 160 128 Leret-Monpezat (Chât.) Péchaussou (Dom. de) Ichard (Dom.) Clos de l’Église Bout du Lieu (Dom. le) Savarines (Dom. des) Bellecoste (Chât.) SCEA Comte J.-B. de Monpezat & DÉCOUVERTES The designation «Vignobles & Décou- C. Péchau & fils J.P. Ichard R. Cantagrel M. & A. Dimani • E. Treuille C. Roucanières 00 33 (0)5 65 20 80 80 ————————————— vertes» is a guarantee of carefully selec- 00 33 (0)5 65 36 51 12 00 33 (0)6 82 37 17 54 00 33 (0)5 65 21 30 89 00 33 (0)6 45 79 85 81 00 33 (0)5 65 22 33 67 00 33 (0)5 65 35 13 47 Ce label c’est l’assurance d’activités et de lieux ted activities and places, enabling you to www.domaineleboutdulieu.com 103 34 82 44 161 129 Cénac (Chât. de) / Port (Chât. du) Latuc (Chât.) Alvina (Chât.) Domaine des Sangliers Fontanelles (Chât. des) Salles (Dom. des) soigneusement sélectionnés, pour vous permettre plan your weekend or short break in the 142 Vignobles PeIvillain • J.F. & G. Meyan • Lacombe & fille L. & K. Stanton Pougette (Clos de) R. Deilhes P. & S. Lasbouygues 00 33 (0)5 65 20 13 13 de préparer plus facilement votre séjour dans le vineyards more easily. All the hotels, 00 33 (0)5 65 36 58 63 • www.latuc.com 00 33 (0)5 65 30 61 10 00 33 (0)5 65 31 61 25 P. -

Rapport Des Services De L'etat

Rapport d’activité des services de l’Etat 2011 2 Rapport d’activité 2011 des services de l’Etat – Préfecture du Morbihan 3 Rapport d’activité 2011 des services de l’Etat – Préfecture du Morbihan 4 Rapport d’activité 2011 des services de l’Etat – Préfecture du Morbihan Préfecture et sous-préfectures PREFECTURE ....................................................................................................................................9 Service du Cabinet et de la Sécurité Publique ..................................................................................... 9 Bureau du Cabinet.................................................................................................................... 9 Mission chargée des gens du voyage..................................................................................... 11 Animation de la politique en faveur de la lutte contre la drogue et la toxicomanie : la mission du directeur de cabinet, chef de projet MILDT ............................................................................. 11 Bureau des politiques de sécurité publique............................................................................ 12 Service interministériel de défense et de protection civile .................................................... 14 Service de la communication interministérielle (SCI)........................................................... 15 Secrétariat Général............................................................................................................................ -

Une Terre D'exception

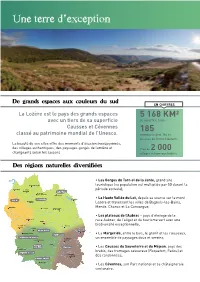

Une terre d’exception De grands espaces aux couleurs du sud EN CHIFFRES La Lozère est le pays des grands espaces 5 168 KM² avec un tiers de sa superficie de superficie totale Causses et Cévennes 185 classé au patrimoine mondial de l’Unesco. communes dont 184 en dessous de 10 000 habitants La beauté de ses sites offre des moments d’évasion insoupçonnés, des villages authentiques, des paysages gorgés de lumière et Plus de 2 000 changeants selon les saisons. villages et hameaux habités Des régions naturelles diversifiées • Les Gorges du Tarn et de la Jonte, grand site touristique (sa population est multipliée par 50 durant la période estivale), • La Haute Vallée du Lot, depuis sa source sur le mont Lozère et traversant les villes de Bagnols-les-Bains, Mende, Chanac et La Canourgue, • Les plateaux de l’Aubrac – pays d’élevage de la race Aubrac, de l’aligot et du tourisme vert avec une biodiversité exceptionnelle, • La Margeride, entre le bois, le granit et les ruisseaux, un ensemble de paysages doux et sereins, • Les Causses du Sauveterre et du Méjean, pays des brebis, des fromages savoureux (Roquefort, Fedou) et des randonnées, • Les Cévennes, son Parc national et sa châtaigneraie centenaire. Les voies de communication Entre Massif Central et Méditerranée, la Lozère se situe au carrefour des régions Auvergne, Midi-Pyrénées, Rhône Alpes et Languedoc-Roussillon dont elle fait partie. Aujourd’hui ouverte et proche de toutes les grandes capitales régionales que sont Montpellier, Toulouse, Lyon et Clermont- Mende Ferrand, la Lozère connait un regain d'attractivité. La Lozère est accessible quelque soit votre moyen de locomotion : Informations mises à jour 7j/7 à 7h, actualisation en journée en fonction de l’évolution des conditions météo En voiture La voiture reste le moyen le plus pratique pour se pendant la période de viabilité déplacer en Lozère. -

Lot-Et-Garonne

Compléme Nom de l'association Adresse de l'association nt CP Ville Montant SIRET d'adresse Accorderie Agenaise 3 rue Bartayres 47000 AGEN 1 000 81916564800026 After Before 108 rue Léo Jouhaux 47500 FUMEL 3 000 42914950300022 Amicale Laïque de EcoleMonsempron maternelle - LIBOS de Monsempron-Libos, place de la mairie 47500 MONSEMPRON-LIBOS 1 000 49931759200016 Archer club Marmandais 104 AVENUE CHRISTIAN BAYLAC 47200 MARMANDE 1 500 44780668800019 Asso Les Archers de Boé CHÂTEAU D'ALLOT 47550 BOE 2 500 38332929900010 ARPE 47 - CPIE LANCELOT 47300 PUJOLS 3 000 33372212200038 Association La Pennoise MAIRIE 47140 PENNE D'AGENAIS 2 000 41439740600037 Association Nord - Nature Orientation RouteRandonnée DE CONDOM Détente 47600 NERAC 1 000 44771535000024 APACT Asso Promotion AnimationRUE Cinéma DU MARECHAL Tonneins FOCH 47400 TONNEINS 1 000 40899530600029 Association Sportive Clairacaise XIII Mairie 47320 CLAIRAC 1500 44848689400018 ToSoCo Madagascar - Tourisme SolidaireLIEU CommunautaireDIT LANCELOT 47300 PUJOLS 1 500 53902409100016 Au Recycle Tout LIEU DIT LABRO 47140ST SYLVESTRE SUR LOT 5 000 82529251900014 Audace-S 1 PLACE NEUF BRISACH 47180MEILHAN SUR GARONNE 1 000 82285194500011 Blue Box Coffee 103 rue Montesquieu 47000 AGEN 5 000 82074393800012 Bric à brac solidaire 61 AV. GENERAL DE GAULLE 47230 LAVARDAC 10 000 81811534700028 La Brigade d'Animation Ludique16 RUE DOCTEUR HENRI FOURESTIE 47000 AGEN 2 000 79204922300029 Café associatif Lou Veratous PLACE DUBARRY 47600 MONCRABEAU 3 400 75300146000017 CDOS 47 - Comité Départemental Olympique997-A, -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

Fire/Rescue Print Date: 3/5/2013

Fire/Rescue Print Date: 3/5/2013 Fire/Rescue Fire/Rescue Print Date: 3/5/2013 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 - MISSION STATEMENT 1.1 - Mission Statement............1 CHAPTER 2 - ORGANIZATION CHART 2.1 - Organization Chart............2 2.2 - Combat Chain of Command............3 2.6 - Job Descriptions............4 2.7 - Personnel Radio Identification Numbers............5 CHAPTER 3 - TRAINING 3.1 - Department Training -Target Solutions............6 3.2 - Controlled Substance............8 3.3 - Field Training and Environmental Conditions............10 3.4 - Training Center Facility PAM............12 3.5 - Live Fire Training-Conex Training Prop............14 CHAPTER 4 - INCIDENT COMMAND 4.2 - Incident Safety Officer............18 CHAPTER 5 - HEALTH & SAFETY 5.1 - Wellness & Fitness Program............19 5.2 - Infectious Disease/Decontamination............20 5.3 - Tuberculosis Exposure Control Plan............26 5.4 - Safety............29 5.5 - Injury Reporting/Alternate Duty............40 5.6 - Biomedical Waste Plan............42 5.8 - Influenza Pandemic Personal Protective Guidelines 2009............45 CHAPTER 6 - OPERATIONS 6.1 - Emergency Response Plan............48 CHAPTER 7 - GENERAL RULES & REGULATIONS 7.1 - Station Duties............56 7.2 - Dress Code............58 7.3 - Uniforms............60 7.4 - Grooming............65 7.5 - Station Maintenance Program............67 7.6 - General Rules & Regulations............69 7.7 - Bunker Gear Inspection & Cleaning Program............73 7.8 - Apparatus Inspection/Maintenance/Response............75 -

Carte Touristique Du

PENDANT VOTRE NOS PLUS BEAUX SÉJOUR DANS LE LOT Villages DEMANDEZ CONSEIL ! Ils sont 8. Huit villages à s’être vu décerner le titre tant convoité de « Plus Beaux Villages de France » : Les applications et sites q Rendez-vous sur Carennac, Loubressac, Autoire, Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, Dublin mobiles des offices de les sites mobiles Capdenac-le-Haut, Cardaillac mais aussi Collonges- Saint-Cirq-Lapopie Birmingham tourisme du Lot sont là pour des offices de la-Rouge et Curemonte. Parce que leurs toits de tuiles Amsterdam Berlin vous conseiller : tourisme du Grand brunes, leurs pierres ocres, leurs fenêtres sculptées Antwerpen Figeac ou de Lot Vignoble. ou encore leurs pigeonniers carrés leur donnent un London q Téléchargez les Brussel cachet exceptionnel, ces villages incarnent à eux seuls l’esprit du Lille Need tourist information for a Carte Touristique applications dédiées Frankfurt Lot. Beaucoup d’autres méritent largement le détour et si tous sont « Mobitour » pour des infos particular territory ? Apps from Paris différents, le charme reste incontestablement leur atout commun : Rennes Luxembourg en Vallée de la Dordogne ou the tourist offices are there ! Marcilhac-sur-Célé, Martel, Puy-l’Évêque, Gourdon sans oublier 2019 Stuttgart entre Cahors et Saint-Cirq- ¿ Necesita información LE LOT Nantes Strasbourg turística en un territorio SANS VOITURE Rocamadour ! Mnchen Lapopie. determinado ? Aplicaciones de Sans voiture, impossible de découvrir le Lot ? Clermont- Genève las oficinas de turismo están allí ! « Que nenni »… Le Lot rime avec contemplation, There are eight of them. Eight villages which have been awarded Bordeaux Ferrand Lyon rêverie, liberté, et sans utiliser la voiture c’est vraiment the much-coveted title « One of the Most Beautiful Villages in France » Milano (Carennac, Loubressac, Autoire, Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, Capdenac- Cahors LE LOT TÉLÉCHARGEZ L’APPLICATION ça. -

Lot Valley – an Overview

Lot Valley – An Overview The beautiful Lot Valley spans five French départments - Lozère, Cantal, Aveyron, Lot and Lot-et-Garonne. The Lot river, whose source is 1,200 metres up Mont Lozere, winds its way through the valley, a backdrop of unspoilt natural beauty filled with medieval bastides, abbeys and castles and a living culture that allows visitors to step back in time and discover a corner of France as it was and as it is. o Taste the outdoors - stunning landscapes (none more so than the dramatic landscapes of the Aubrac Peninsula at the eastern end of the valley), picturesque villages, a region that has been a favourite muse of French artists for centuries, home to a remarkable diversity of wildlife of butterflies, birds, insects and flowers. o Outdoor activities – messing about on the river – boating, windsurfing, sailing, swimming, fishing, canoeing, canyoning, tubing and white water rafting. Stick to dry land – horse riding, hiking, climbing, skiing, cycling and fishing . Take to the air – handgliding or head underground – caving o Relax and rejuvenate – there are several thermal springs in the Upper Lot Valley and the spring in the village of Chaude Aigues in the Cantal, has the hottest thermal spring in Europe at 82˚C. The spa La Chaldette in Lozère, at 1000 metres altitude, is also a must. o Take a journey through time - home to some of Europe’s most impressive pre-historic cave art, centuries-old castles, abbeys, bastides and Medieval villages survive as they were, the Roman abbey at Conques, (Aveyron), the castle Château de Cénevières, St Cirq Lapopie in the Lot and the beautiful Bastide of Mont Flanquin in Lot-et-Garonne. -

Set Off for the Gulf of Morbihan Blue and Green Everywhere, Islands and Even Sea Horses

TRIP IDEA Set off for the Gulf of Morbihan Blue and green everywhere, islands and even sea horses... On and below the water, you’ll be amazed by the Gulf of Morbihan, the jewel of Southern Brittany! AT A GLANCE Somewhere beyond the sea.... on the Gulf of Morbihan. Admire the constantly changing reflections of the “Small land-locked sea” of Southern Brittany. Stroll through its medieval capital, Vannes, the banks of which lead to the Gulf. Hop on an old sailing ship to enjoy the delights of navigating. Opt for a complete change of scenery by going for a dive from the Rhuys peninsular. The sea beds here are full of surprises! Day 1 A stroll in Vannes, the capital of the Gulf Welcome to Vannes! A pretty town nestled on the Gulf of Morbihan which enjoys a particular atmosphere that is both medieval and modern. Stroll through its garden at the foot of the remarkably well-preserved ramparts. Wander around the centre of the walled city. You'll discover Place des Lices, Saint-Pierre cathedral, the Cohue museum, etc. Don’t miss the very photogenic Place Henri IV with its leaning half-timbered houses. The Saint-Patern district, which is like a little village, is also a must-see. After lunch, take a walk between the marina and the Conleau peninsular. Over a distance of 4.5 km (9 km there and back), you’ll pass the lively city-centre quays and the restful Pointe des Emigrés. On one side, you’ll have the pine forest. On the other, marshes and salt-meadows.