Skillful Example of Popular History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologists of Russian Origin in Latin America

REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1 , A.C. Riccardi 2 , †M. Durand Delga3 , R. Alonso 4 , 7 8 M. Wiasemsky5 , D. Boltovskoy 6 , R. Charrier , E. Minina 1Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3Passed away August19, 2012 4Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 581, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6Dep. Ecologia, Genetica y Evolucion, Fac. Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Univ. de Buenos Aires, Argentina, [email protected] 7History of Geology Group, Sociedad Geológica de Chile, Santiago de Chile, [email protected] 8State Geological Museum “V.I.Vernadsky”, Mohovaya ul. 11/11, Moscow 125009, Russian Federation, [email protected] REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA / 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 / ISSN 2545-6377 ISSN 2545-6377 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE LA PLATA - FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS NATURALES Y MUSEO Revista del Museo de La Plata 2018 Volumen 3, Número 2 (Julio-Diciembre): 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1, A.C. Riccardi2, †M. Durand Delga3, R. Alonso4, M. Wiasemsky5, D. Boltovskoy6, R. Charrier7, E. Minina8 1 Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2 Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3 Passed away August19, 2012 4 Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 5 81, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6 Dep. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

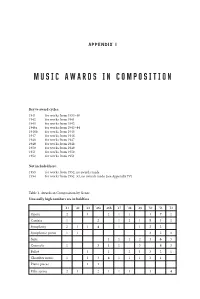

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Operatic Roots of Prokofyev’S

THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIAN OPERATIC ROOTS OF PROKOFYEV’S WAR AND PEACE by TERRY LYNN DEAN, JR. (Under the Direction of David Edwin Haas) ABSTRACT More than fifty years after Prokofyev’s death, War and Peace remains a misunderstood composition. While there are many reasons why the opera remains misunderstood, the primary reason for this is the opera’s genesis in Stalinist Russia and his obligation to uphold the “life-affirming” principles of the pro-Soviet aesthetic, Socialist Realism, by drawing inspiration from the rich heritage “Russian classical” opera—specifically the works of Glinka, Chaikovsky, and Musorgsky. The primary intent of this dissertation is to provide new perspectives on War and Peace by examining the relationship between the opera and the nineteenth-century Russian opera tradition. By exploring such a relationship, one can more clearly understand how nineteenth-century Russian operas had a formative effect on Prokofyev’s opera aesthetic. An analysis of the impact of the Russian operatic tradition on War and Peace will also provide insights into the ways in which Prokofyev responded to official Soviet demands to uphold the canon of nineteenth-century Russian opera as models for contemporary composition and to implement aspects of 19th-century compositional practice into 20th-century compositions. Drawing upon the critical theories of Soviet musicologist Boris Asafyev, this study demonstrates that while Prokofyev maintained his distinct compositional voice, he successfully aligned his work with the nineteenth-century tradition. Moreover, the study suggests that Prokofyev’s solution to rendering Tolstoy’s novel as an opera required him to utilize a variety of traits characteristic of the nineteenth-century Russian opera tradition, resulting in a work that is both eclectic in musical style and dramaturgically effective. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} the Mystery of Olga Chekhova: The

THE MYSTERY OF OLGA CHEKHOVA: THE TRUE STORY OF A FAMILY TORN APART BY REVOLUTION AND WAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Antony Beevor | 336 pages | 05 Nov 2005 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141017648 | English | London, United Kingdom The Mystery of Olga Chekhova After fleeing Bolshevik Moscow for Berlin in , she was recruited by her composer brother Lev, to work for Soviet intelligence. In return, her family were allowed to join her. The extraordinary story of how the whole family survived the Russian Revolution, the civil war, the rise of Hitler, the Stalinist Terror, and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union becomes, in Antony Beevor's hands, a breathtaking tale of compromise and survival in a merciless age. I didn't think twice when I encountered this book at a book store - anything relating to the great Russian writer should be worthy of reading. And it was. Even though Anton Chekhov is hardly mentioned This is an account of the colourful life of the niece of the famous author and playwright and his theatre actress wife Olga Knipper-Chekhova. A minor theatre and early film actress before the Russian The Mystery of Olga Chekhova : The true story of a family torn apart by revolution and war. Antony Beevor. The Cherry Orchard of Victory. Knippers and Chekhovs. There is no single murder, suspect or detective. This is the true story of an extremely brave and cunning woman. Who is this Mystery Woman? Olga Chekhova, the niece of the great Playwright, Anton Chekhov. Running away from her home in Russia, in her teens, to escape starvation, she plays up the Chekhov name and association to land a small part in a Silent Film. -

Between Tradition and Modernity

Between Tradition and Modernity Sergei Vasilenko and His Unknown Works for Viola and Piano By Elena Artamonova A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD in Performance Practice Department of Music, Goldsmiths College University of London Volume 1 Date: 12 January, 2014 Signed Declaration I, Elena Artamonova, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Elena Artamonova Date: 12 January, 2014 2 Acknowledgements This thesis would have not been possible without the help and support of many people. First and foremost, I am indebted to my research supervisor, Professor Alexander Ivashkin, whose thorough guidance and continuous professional and moral support provided inimitable opportunities for my study. Without his exceptional proficiency and advice this project would have never materialised in this form. I am very grateful for practical guidance of Professors Tabea Zimmermann (Hanns Eisler Hochschule fűr Musik, Berlin) and Nobuko Imai (Geneva Conservatoire), who openly shared their unique expertise in solo viola performance. I am obliged to the pianist Nicholas Walker (Royal Academy of Music, London), who has collaborated with me on the CD recording ‘Sergei Vasilenko: Complete Music for Viola and Piano. First Complete Recording’ and our numerous concert performances, and also helped to interpret and decipher the handwritten manuscripts of the musical scores that I was fortunate to find during the course of this research. I am thankful to the music publisher of the Toccata Classics, Martin Anderson, for his commission and collaboration in the production of the CD recording ‘Sergei Vasilenko’ mentioned above. -

Lev Knipper: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music 1924

LEV KNIPPER: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1924-27: Suite “Skazhi gipsovovo bozhka”, op.1 1924: Romance in Five Verses for tenor and orchestra, op.2 “She Knows All About Spring” for singer and orchestra, op.3B Ballet “Satanella”, op.4 Poem “Legend of a Plaster God” for orchestra, op.4 1925: Revolutionary Episodes for orchestra, op.9 Two Songs after Blok for singer and orchestra, op.10 1925-26: Three Pieces for orchestra, op. 12 1926-27: Ballet Suite “Candide”, op.15A 1927: Symphony No.1, op.13 1928: Lyric Suite for chamber orchestra, op.18 1928-32: Symphony No.2 “Lyric”, op.30 1929: Suite for orchestra, op.19 Ballet “The Small Negro”, op.24 1931: Tatzhikian Suite for orchestra, op.28 Tatzhikian Suite “Vauch” for orchestra, op.29 Suite “Stalinabad” for orchestra 1932: Suite “Memories” for Violin and Orchestra, op.31 Sinfonietta “Till Eulenspiegel”, op. 33 1932-33: Symphony No.3 “The Far East Army” for soloists, male chorus, military brass band and orchestra, op.32 1933: Overture “Vakhio Bolo” Tatzhikian Dances for orchestra Four Studies for orchestra, op.34 Three Russian Folk Songs for voice and small orchestra, op.35 1933-34: Symphony No.4 “Poem for the Komsomol Fighters” in D major for tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.41: 33 minutes + (Melodiya and Olympia cds) Symphony No.5 “Lyric Poem”, op.42 1934: Four Ballet Etudes “Till Eulenspiegel” for orchestra, op.43 Sinfonietta No.1 for string orchestra Tatzhikian Suite No.2 for orchestra Eight Love Songs for singer and chamber orchestra, op.45 1935: Tatzhikian Suite No.2 for -

Revista Del Museo De La Plata

REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1 , A.C. Riccardi 2 , †M. Durand Delga3 , R. Alonso 4 , 7 8 M. Wiasemsky5 , D. Boltovskoy 6 , R. Charrier , E. Minina 1Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3Passed away August19, 2012 4Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 581, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6Dep. Ecologia, Genetica y Evolucion, Fac. Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Univ. de Buenos Aires, Argentina, [email protected] 7History of Geology Group, Sociedad Geológica de Chile, Santiago de Chile, [email protected] 8State Geological Museum “V.I.Vernadsky”, Mohovaya ul. 11/11, Moscow 125009, Russian Federation, [email protected] REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA / 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 / ISSN 2545-6377 ISSN 2545-6377 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE LA PLATA - FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS NATURALES Y MUSEO Revista del Museo de La Plata 2018 Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1, A.C. Riccardi2, †M. Durand Delga3, R. Alonso4, M. Wiasemsky5, D. Boltovskoy6, R. Charrier7, E. Minina8 1 Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2 Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3 Passed away August19, 2012 4 Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 5 81, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6 Dep. -

Modified String Quartet Practices in Post-Soviet Eurasia" (2013)

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2013 A New Kind of National: Modified String Quartet Practices in Post- Soviet Eurasia Adam Taylor Lenz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Lenz, Adam Taylor, "A New Kind of National: Modified String Quartet Practices in Post-Soviet Eurasia" (2013). Master's Theses. 162. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/162 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW KIND OF NATIONAL: MODIFIED STRING QUARTET PRACTICES IN POST-SOVIET EURASIA by Adam Taylor Lenz A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Music Western Michigan University June 2013 Thesis Committee: Matthew Steel, Ph.D., Chair David Loberg Code, Ph.D. Christopher Biggs, D.M.A. ! A NEW KIND OF NATIONAL: MODIFIED STRING QUARTET PRACTICES IN POST-SOVIET EURASIA Adam Taylor Lenz, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This thesis examines the practices of string quartet modification implemented by three post-Soviet Eurasian composers: Franghiz Ali-Zadeh (Azerbaijan), Vache Sharafyan (Armenia), and Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky (Uzbekistan). After an introduction to the geography of the region and the biographies of the composers, their works containing modified string quartet configurations are examined within three distinct modification practices. -

Moscow 1941 Student Portfolio

Patrick Marsh Middle School Instrumental Music Department Chris Gleason, Band Director NAME___________________________ 7th GRADE 6th Hour BAND Third Quarter PORTFOLIO Build Myelin My Plan To Practice Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Moscow 1941 The song identifies with an extremely important moment in history during the Second World War, in which the Red Army, against all odds, successfully defended Moscow against the German invasion. In October 1941, German troops were only 15 miles outside of Moscow, an unfavorable situation for the Soviet Union. Two million people had evacuated Moscow, but Joseph Stalin stayed to rally morale. In November, the Germans launched a new attack on Moscow. The Soviet Army held their ground and brought the Germans to a halt. Stalin insisted on a counterattack; and although his commanders had doubts, they launched their own offensive on December 4.The Germans, caught off guard and demoralized by the recent defeat, were pushed back and began retreating. By January, they had been pushed back nearly 200 miles. Soviet Army in Counterattack Moscow Kremlin The Tune….”Meadowland” "Polyushko Pole" (Meadowland) is a Russian song. It is claimed that the song was originally written during the Russian Civil War and was sung by the Red Army. For the Soviet variant of the song, the music was by Lev Knipper, with lyrics by Viktor Gusev. Knipper's song was part of the symphony with chorus (lyrics by Gusev) "A Poem about a Komsomol Soldier" composed in 1934. It was covered many times by many artists in the Soviet Union. Several Western arrangements of the tune are known under the title "The Cossack Patrol", particularly a version by Ivan Rebroff, and some under other titles including "Meadowland", "Cavalry of the Steppes" and "Gone with the Wind". -

B (S20) LISTENING LOG: E—L PETER EBEN Laudes Earliest Work

20 B♭ (S ) LISTENING LOG: E—L PETER EBEN Laudes Earliest work on the CD by Czech avant garde organist. Atonal, dissonant, but deals with recognizable motives and gestures. Somewhere there’s a Gregorian theme. There are four movements, the first is agitato. The second begins with extreme low and high pitches, loud rhythmic middle. The third has a weird mute stop. The fourth begins pianissimo, isolated notes on lowest pedals. (Mh17) Hommage à Buxtehude Good-humored toccata, then fantasy on a repeated note motif. Dissonant but light. (Mh17) Job Mammoth 43`organ work in 8 movements, each headed by a verse from Job. The strategy resembles Messiaen`s, but the music is craggier and I suspect less tightly organized. (1) Destiny: Job is stricken. Deep pedals for terror, toccata for agitation. (2) Faith: The Lord gives and takes away: Flutes sound the Gregorian Exsultet interrupted by terrible loud dissonance – agitation has turned to trudging, but ends, after another interruption, with muted Gloria. (3) Acceptance: After another outcry, Job is given a Bach chorale tune, “Wer nur den lieben Gott,” a hymn of faith – wild dissonances followed again by chorale. (4) Longing for Death: a passacaglia builds to climax and ends in whimpering ppp. (5) Despair and Resignation: Job`s questioning and outbursts of anger, followed by legato line of submission. (6) Mystery of Creation: eerie quiet chords and flutings, crescendo – rapid staccato chords, accelerando as if building anger – block chords fortissimo – solo flute question. (7) Penitance and Realization: Solo reed with ponderous pedal – chattering, hardly abject! – final bit based on Veni Creator.