Modified String Quartet Practices in Post-Soviet Eurasia" (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis and Overall Evaluation of Elt

Istanbul University Institute of Social Sciences Foreign Language Teaching Department English Language Teaching Division A Master’s Thesis A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND OVERALL EVALUATION OF ELT COURSEBOOKS PREPARED IN UZBEK, TURKISH AND ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING CONTEXTS IN TERMS OF COMMUNICATIVE SKILLS BUILDING Jamola Urunboeva 2501091223 Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Muazzez Yavuz Kırık Istanbul 2012 ABSTRACT A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND OVERALL EVALUATION OF ELTCBS PREPARED IN UZBEK, TURKISH AND ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING CONTEXTS IN TERMS OF COMMUNICATIVE SKILLS BUILDING JamolaUrunboeva This study evaluated the three Eighth Grades Intermediate English CBs (CBs) published in Uzbekistan, Turkey and the UK. Fly High English 8 was published by the Ministry of Education of Uzbekistan, English Net 8 was published as a representative CB taught in the primary schools in Turkey, and Solutions Intermediate was published by Oxford University Press and is considered to be a commercial CB, which was selected as a supplementary one to compensate the other two CBs. The main purpose of the study is to evaluate how the above mentioned CBs reflect communicative skills building. Further, these CBs are analysed comparatively within the central question the extent to which these three CBs could have commonalities in skill objectives reflected in curriculums in terms of student`s mobility, since to equip students for the challenges of intensified international mobility and closer co-operation is the crucial objective of The Common European Framework of Reference. In this context revealing the strengths and weaknesses in the CBs, determining how well the CBs meet the standards of a good textbook in terms of communicative skills building, resolving to what extent do the CBs would expose commonalities in curriculums, aims and objectives and deciding whether they are suitable, or need supplementation for optimal learning is important for this study. -

5 Music Cruises 2019 E.Pub

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart RHINE 2019 DUDOK QUARTET Aer compleng their studies with disncon at the Dutch String Quartet Academy in 20 3, the Quartet started to have success at internaonal compeons and to be recognized as one of the most promising young European string quartets of the year. In 20 4, they were awarded the Kersjes ,rize for their e-ceponal talent in the Dutch chamber music scene. .he Quartet was also laureate and winner of two special prizes during the 7th Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 3 1 2ordeau- and won st place at both the st Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 in 3adom 4,oland5 and the 27th 0harles 6ennen Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompe7 on 20 2. In 20 2, they received 2nd place at the 8th 9oseph 9oachim Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompeon in Weimar 4:ermany5. .he members of the quartet ;rst met in the Dutch street sym7 phony orchestra “3iccio=”. From 2009 unl 20 , they stu7 died with the Alban 2erg Quartet at the School of Music in 0ologne, then to study with Marc Danel at the Dutch String Quartet Academy. During the same period, the quartet was coached intensively by Eberhard Feltz, ,eter 0ropper 4Aindsay Quartet5, Auc7Marie Aguera 4Quatuor BsaCe5 and Stefan Metz. Many well7Dnown contemporary classical composers such as Kaija Saariaho, MarD7Anthony .urnage, 0alliope .sou7 paDi and Ma- Knigge also worDed with the quartet. In 20 4, the Quartet signed on for several recordings with 3esonus 0lassics, the worldEs ;rst solely digital classical music label. -

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

Geologists of Russian Origin in Latin America

REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1 , A.C. Riccardi 2 , †M. Durand Delga3 , R. Alonso 4 , 7 8 M. Wiasemsky5 , D. Boltovskoy 6 , R. Charrier , E. Minina 1Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3Passed away August19, 2012 4Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 581, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6Dep. Ecologia, Genetica y Evolucion, Fac. Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Univ. de Buenos Aires, Argentina, [email protected] 7History of Geology Group, Sociedad Geológica de Chile, Santiago de Chile, [email protected] 8State Geological Museum “V.I.Vernadsky”, Mohovaya ul. 11/11, Moscow 125009, Russian Federation, [email protected] REVISTA DEL MUSEO DE LA PLATA / 2018, Volumen 3, Número 2: 223-295 / ISSN 2545-6377 ISSN 2545-6377 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE LA PLATA - FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS NATURALES Y MUSEO Revista del Museo de La Plata 2018 Volumen 3, Número 2 (Julio-Diciembre): 223-295 Geologists of Russian origin in Latin America P. Tchoumatchenco1, A.C. Riccardi2, †M. Durand Delga3, R. Alonso4, M. Wiasemsky5, D. Boltovskoy6, R. Charrier7, E. Minina8 1 Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Acad. G. Bonchev Str. Bl. 24, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria, [email protected] 2 Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina, [email protected] 3 Passed away August19, 2012 4 Universidad Nacional de Salta, Argentina, [email protected] 5 81, Chemin du Plan de Charlet, F-74190 Passy, France, [email protected] 6 Dep. -

Quatuor Ébène Pierre Colombet Violin • Gabriel Le Magadure Violin Marie Chilemme Viola • Raphaël Merlin Cello

Wednesday 12 December 2018 7.30pm Quatuor Ébène Pierre Colombet violin • Gabriel Le Magadure violin Marie Chilemme viola • Raphaël Merlin cello Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet in F Op. 18 No. 1 Johannes Brahms String Quartet in C minor Op. 51 No. 1 I n t e r v a l (20 minutes) Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet in F Op. 135 This evening’s concert will be streamed live, and will be available to watch afterwards on the Wigmore Hall website. PROGRAMME: £3 CAVATINA Chamber Music Trust has donated free tickets for 8-25 year-olds for the concert on 12 December 2018. For details of future concerts please call the Box Office on 020 7935 2141. 2018 cover-autumn test print.indd 1 29/08/2018 10:28 Ludwig van Beethoven Beethoven arrived in Vienna in 1792, a year after Mozart’s tragic death. The young, (1770–1827) Bonn-born composer was effectively travelling to the Habsburg capital to take up where the late, lamented composer had String Quartet in F Op. 18 No. 1 left off. He even carried a letter to that end, (1798–1800) written by his friend Count von Waldstein: Allegro con brio ‘You are going to Vienna in fulfilment Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato of your long-frustrated wishes. The Scherzo. Allegro molto Genius of Mozart is still mourning and Allegro weeping the death of her pupil. She found a refuge but no occupation with the inexhaustible Haydn; through him Johannes Brahms she wishes once more to form a union (1833–1897) with another. -

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments

Intraoral Pressure in Ethnic Wind Instruments Clinton F. Goss Westport, CT, USA. Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Initially published online: High intraoral pressure generated when playing some wind instruments has been December 20, 2012 linked to a variety of health issues. Prior research has focused on Western Revised: August 21, 2013 classical instruments, but no work has been published on ethnic wind instruments. This study measured intraoral pressure when playing six classes of This work is licensed under the ethnic wind instruments (N = 149): Native American flutes (n = 71) and smaller Creative Commons Attribution- samples of ethnic duct flutes, reed instruments, reedpipes, overtone whistles, and Noncommercial 3.0 license. overtone flutes. Results are presented in the context of a survey of prior studies, This work has not been peer providing a composite view of the intraoral pressure requirements of a broad reviewed. range of wind instruments. Mean intraoral pressure was 8.37 mBar across all ethnic wind instruments and 5.21 ± 2.16 mBar for Native American flutes. The range of pressure in Native American flutes closely matches pressure reported in Keywords: Intraoral pressure; Native other studies for normal speech, and the maximum intraoral pressure, 20.55 American flute; mBar, is below the highest subglottal pressure reported in other studies during Wind instruments; singing. Results show that ethnic wind instruments, with the exception of ethnic Velopharyngeal incompetency reed instruments, have generally lower intraoral pressure requirements than (VPI); Intraocular pressure (IOP) Western classical wind instruments. This implies a lower risk of the health issues related to high intraoral pressure. -

There's Even More to Explore!

Background artwork: SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UCHICAGO LIBRARY Kaplan and Fridkin, Agit No. 2 MUSIC THEATER ART MUSIC THEATER LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC / FILM LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC University of Chicago Presents University Theater/Theater and Performance Studies The University of Chicago Library Symphony Center Presents Goodman Theatre University of Chicago Presents Roosevelt University Rockefeller Chapel University of Chicago Presents TOKYO STRING QUARTET THEATER 24 PLAY SERIES: GULAG ART Orchestra Series CHEKHOv’S THE SEAGULL LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN PAciFicA QUARTET: 19TH ANNUAL SILENT FiLM LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN BY MARiiNskY ORCHESTRA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 A CLOUD WITH TROUSERS THROUGH DECEMBER 2010 OCTOber 16 – NOVEMBER 14, 2010 BY PACIFICA QUARTET SHOSTAKOVICH CYCLE WITH ORGAN AccomPANimENT: MAsumi RosTAD, VioLA, AND (FORMERLY KIROV ORCHESTRA) Mandel Hall, 1131 East 57th Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2010, 8 PM The Joseph Regenstein Library, 170 North Dearborn Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 17, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS AMY BRIGGS, PIANO th nd chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 First Floor Theater, Reynolds Club, 1100 East 57 Street, 2 Floor Reading Room Valery Gergiev, conductor Goodmantheatre.org, 312.443.3800 Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 31, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM Jay Warren, organ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2 PM 5706 South University Avenue Lib.uchicago.edu Denis Matsuev, piano Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2010, 8 PM Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street Mozart: Quartet in C Major, K. 575 As imperialist Russia was falling apart, playwright Anton SUNDAY JANUARY 30, 2011, 2 AND 7 PM ut.uchicago.edu TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2010, 8 PM Rockefeller Chapel, 5850 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 Lera Auerbach: Quartet No. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Circus Arts at O.Z.O.R.A

THE DAILY NEWSPAPER OF THE OZORIAN TRIBE FREE * 4 PAGES SUNDAY AUGUST, 2012 ozorafestival.eu spiced with some dark humor in vaudeville style. The spectacu- lar juggling, acrobatic, trapeze and burlesque dance performers Circus Arts at O.Z.O.R.A. are the s-cream of the international underground circus life.The characters of the performance keep their masks on even after AT THIS YEAR’S FESTIVAL THE their show, mingling with the MODERN CIRCUS ARTS GOT A SPE- audience and further building CIAL SPACE. INTERNATIONALLY the atmosphere, so anything FAMOUS AND PROFESSIONAL CIR- can happen anywhere at any CUS AND JUGGLING GROUPS ARE time! PERFORMING AT THE OPENING CEREMONY AND ON DIFFERENT A new stage at the festival is the STAGES OF THE FESTIVAL. Firespace, this is a project from Germany essentially an open space for fire dancers and fire On the main stage legendary fire jugglers, supports a diversity of artists, like Magma Fire Theather, fire arts. Moreover, we regard Flame Flowers, Firebirds, Freak Fu- Fire Space as a cultural space, sion Cabaret, Anamintas Fire The- allowing for inspiration and in- ather, Mietar, Spark Firedance, Los teraction seeks the best condi- Del Fuego and Firesthetic are pre- tions for audience and artists, senting their new and special proj- as well as for environment and ects. It is also an important mission material. The space is open for us to teach the flow arts. We from dusk till dawn, come by hold and held workshops, where with your fire gear and spin people can try out all kinds of body with us or just sit down around manipulation, circus, juggling and the circle and enjoy the show! acrobatic arts with experienced trainers and safe equipments. -

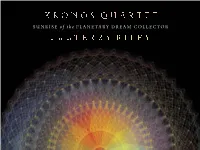

Kronos Quartet

K RONOS QUARTET SUNRISE o f the PLANETARY DREAM COLLECTOR Music o f TERRY RILEY TERRY RILEY (b. 1935) KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, VIOLIN 1. Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector 12:31 John Sherba, VIOLIN Hank Dutt, VIOLA 2. One Earth, One People, One Love 9:00 CELLO (1–2) from Sun Rings Sunny Yang, Joan Jeanrenaud, CELLO (3–4, 6–16) 3. Cry of a Lady 5:09 with Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares Jennifer Culp, CELLO (5) Dora Hristova, conductor 4. G Song 9:39 5. Lacrymosa – Remembering Kevin 8:28 Cadenza on the Night Plain 6. Introduction 2:19 7. Cadenza: Violin I 2:34 8. Where Was Wisdom When We Went West? 3:05 9. Cadenza: Viola 2:24 10. March of the Old Timers Reefer Division 2:19 11. Cadenza: Violin II 2:02 12. Tuning to Rolling Thunder 4:53 13. The Night Cry of Black Buffalo Woman 2:53 1 4. Cadenza: Cello 1:08 15. Gathering of the Spiral Clan 5:24 16. Captain Jack Has the Last Word 1:42 from left: Joan Jeanrenaud, John Sherba, Terry Riley, Hank Dutt, and David Harrington (1983, photo by James M. Brown) Sunrise of the Planetary possibilities of life. It helped the Dream Collector (1980) imagination open up to the possibilities It had been raining steadily that day surrounding us, to new possibilities in 1980 when the Kronos Quartet drove up curiosity he stopped by to hear the quartet Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector for interpretation.” —John Sherba to the Sierra Foothills to receive Sunrise practice. -

Tezfiatipnal "

tezfiatipnal" THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Borodin Quartet MIKHAIL KOPELMAN, Violinist DMITRI SHEBALIN, Violist ANDREI ABRAMENKOV, Violinist VALENTIN BERLINSKY, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 25, 1990, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 .............................. PROKOFIEV Allegro sostenuto Adagio, poco piu animate, tempo 1 Allegro, andante molto, tempo 1 Quartet No. 3 (1984) .......................................... SCHNITTKE Andante Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, with Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 ...... BEETHOVEN Adagio, ma non troppo; allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alia danza tedesca: allegro assai Cavatina: adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge The Borodin Quartet is represented exclusively in North America by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, Inc., San Francisco. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twenty-eighth Concert of the lllth Season Twenty-seventh Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 ........................ SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev, born in Sontsovka, in the Ekaterinoslav district of the Ukraine, began piano lessons at age three with his mother, who also encouraged him to compose. It soon became clear that the child was musically precocious, writing his first piano piece at age five and playing the easier Beethoven sonatas at age nine. He continued training in Moscow, studying piano with Reinhold Gliere, and in 1904, entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Anatoly Lyadov, orchestration with Rimsky- Korsakov, and conducting with Alexander Tcherepnin. -

Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing

The Music of Central Asia: Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing The editors welcome additions, updates, and corrections to this compilation of resources on Central Asian Music. Please submit bibliographic/discographic information, following the format for the relevant section below, to: [email protected]. Titles in languages other than English, French, and German should be translated into English. Titles in languages written in a non-Roman script should be transliterated using the American Library Association-Library of Congress Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts, available at: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/roman.html Print Materials and Websites 1. Anthropology of Central Asia 2. Central Asian History 3. Music in Central Asia (General) 4. Musical Instruments 5. Music, Sound, and Spirituality 6. Oral Tradition and Epics of Central Asia 7. Contemporary Music: Pop, Tradition-Based, Avant-Garde, and Hybrid Styles 8. Musical Diaspora Communities 9. Women in Central Asian Music 10. Music of Nomadic and Historically Nomadic People (a) General (b) Karakalpak (c) Kazakh (d) Kyrgyz (e) Turkmen 11. Music in Sedentary Cultures of Central Asia (a) Afghanistan (b) Azerbaijan (c) Badakhshan (d) Bukhara (e) Tajik and Uzbek Maqom and Art Song (f) Uzbekistan (g) Tajikistan (h) Uyghur Muqam and Epic Traditions Audio and Video Recordings 1. General 2. Afghanistan 3. Azerbaijan 4. Badakhshan 5. Karakalpak 6. Kazakh 7. Kyrgyz 8. Tajik and Uzbek Maqom and Art Song 9. Tajikistan 10. Turkmenistan 11. Uyghur 12. Uzbekistan 13. Uzbek pop 1. Anthropology of Central Asia Eickelman, Dale F. The Middle East and Central Asia: An Anthropological Approach, 4th ed. Pearson, 2001.