Health Impact Assessment of Rainier Rapidride Bus Rapid Transit Project June 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study Final Report February 2014 (this page left blank intentionally) Initial Segment and Airport Link Before and After Study – Final Report (Feb 2014) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Before and After Study Requirement and Purposes ................................................................................................... 1 Project Characteristics ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Milestones .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Data Collection in the Fall .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................................ 2 History of Project Planning and Development ....................................................................................................... 2 Characteristic 1 - Project Scope .............................................................................................................................. 6 Characteristic -

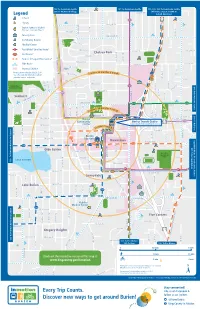

Every Trip Counts. Discover New Ways to Get Around Burien!

Southwest 131st Street 7th Avenue South 120: To Downtown Seattle 131: To Downtown Seattle 121, 122, 123: To Downtown Seattle SW 132nd St 560: To Westwood Village S 132nd St (All routes stop at S 128thS 132n Std St Legend in both directions) School W S 509 e 131 v A Library ED MUNRO h t SW 134th St SEAHURST PARK 2 Burien Farmer’s Market 1 Thursdays, 11am -6pm, May-Oct SW 135th St 8th Ave SW Grocery Store 6th Ave SW SW 136th St S Ave 7th 1 6 Community Garden t h 1 A SW 13 2 6 th P ve t l Medicalnue Center h So u A t v h e w S RapidRidee F Line Bus Route* s SW 137th St W t S 138th St S 138th St W Chelsea Park W S 120 S Bus Routes* St e SW 138th e v A v A m A d Peak or Infrequent Bus Service* t b s n 1 a 2 u SW 139th St W m Pl S S 140th St 6th Bike Route S 140th St 1 B 141st S l W t v S Business District d Stairs S W 0 min or *Routes shown effective July 28, 2014. = 2 6 m S ile in 123 W 142 m 7th Pl S nd 1 S See other side for information about t 122 S 142nd St 1 potential service reductions. 5th Ave S 1 t h 121 S 142nd Ln 1 1 A SW 14 3 2 2 n t v d h t e h P d St SW 143r A l A S a v v W c 131 Downtown Seattle 132: To e ED MUNRO e l e P d S r 5 S 3 SEAHURST PARK 6th Ave S W t 4 W 1 120 h S 4th Ave S SW 144th St A v 560 e S Pl Seahurst th THE 44 1 ANNEX S Ave 1st SW SW 146th St South Place 5th 132 W 132 S S 146th St e S e v W h o v i u t r S A t W u h D S e in o l h m w t S 10 or 3 v t S = m r a e e i A l i 4 s e n i r e u S 147th St t t 1 m 146th Stree v h u o t ½ n A 7 m Co e v e h A h t h M t t 9th Ave SW 560: To Bellevue 560: To 8 1 560: -

King County Metro Update

King County Metro Update Regional Transportation Issues, Challenges, and Successes November 2015 Presentation Outline . RapidRide Update . Focus on F Line . Expanding Alternative Services Program . Service Guidelines Task Force . Long Range Plan 2 Six RapidRide Lines 2010 – 2014 • F Line Implemented June 2014 – Supported by Burien, Sea-Tac, Tukwila, Renton 3 3 Boardings By Day of the Week RapidRide F Line F Line - September 2015 6000 5,510 151,600 5000 Monthly Riders 4,430 3,790 (September 2015) 4000 3,630 3000 2000 1000 0 Pre-RapidRide Weekday Saturday Sunday 4 4 Ridership Growth Over Pre-RapidRide Baseline F Line has met its YTD September 2015 five year goal in 90% 84% one year 78% 80% 70% 60% 52% 50% 51% 50% 40% 35% 31% 30% 20% 10% 0% A Line B Line C Line D Line E Line F Line Average 5 5 F Line Performance Measures Customer Satisfaction . Overall satisfaction 88% . Better experience 83% . Trip time 84% . Reliability 84% . Personal safety (on bus) 79% 6 6 Alternative Services Program Overview Provide mobility services to parts of King County that do not have the infrastructure, density, or land use to support traditional fixed-route bus service. Community Based Process . New Service/Product Options . Creative Solutions 7 Options Real-Time Existing Alternative Community Shuttle Community Van Services Rideshare TripPool Metro route with a A fleet of Metro vans Leveraging mobile VanShare Flexible Service Area, for local group trips Real-time applications to provided through which are scheduled ridesharing between VanPool enable private community by a local home neighborhood carpool Rideshare Matching partnerships. -

WSTA Week in Review

WSTA Week in ReviAprilew 16, 2014 June 14, 2015 , 2015 CELEBRATING PUBLIC TRANSIT Mason Transit Authority Named 2015 Rural Community Transportation System of the Year! (From Community Transportation Association of America) Tampa, Fla. – June 3, 2015. Mason Transit Authority of Shelton, Washington, was named today the 2015 Rural Community Transportation System of the Year by the Community Transportation Association of America at its annual Awards Banquet, held this year in Tampa, Fla. The system was recognized for its efforts in improving service to its passengers and serving the community. The award, presented annually at the Association’s national EXPO, recognizes excellence by rural transit systems in serving the needs of people in their communities. Association Board Regional Director Barbara Cline, CCTM, in presenting the award, said the organization “offers proof that amazing things can happen when like-minded people work together for the common good. This county-wide rural operator has made words like innovative and creative far more than mere slogans, they are part of the agency’s everyday operation.” Cline also noted Mason Transit Authority’s After School Activities Bus service, partnership with a local tribal government, its vanpool service transporting more than 150 daily workers to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyards and the opening of the nation’s first rural, joint transit-community center as key factors in the system’s selection as rural system of the year. Jefferson Transit Authority Celebrates Grand Opening of New Building Jefferson Transit Authority (JTA) celebrated the opening of its new transportation hub at 63 Four Corners Road in Port Townsend on June 12. -

King County Metro 4

1 of 13 Funding Application Competition Regional FHWA Application Type Corridors Serving Centers Status submitted Submitted: April 8th, 2020 4:26 PM Prepopulated with screening form? No Project Information 1. Project Title RapidRide I Line: Speed and Reliability Improvements 2. Regional Transportation Plan ID 5674 3. Sponsoring Agency King County Metro 4. Cosponsors N/A 5. Does the sponsoring agency have "Certification Acceptance" status from WSDOT? Yes 6. If not, which agency will serve as your CA sponsor? N/A Contact Information 1. Contact name Eric Irelan 2. Contact phone (206)477-3862 3. Contact email [email protected] Project Description 1. Project Scope The project scope will provide for the construction and implementation of transit speed and reliability improvements for the RapidRide I Line which is scheduled to begin service in 2023. This proposal covers critical elements of the planned RapidRide I Line speed and reliability improvements with in the City of Renton. It will provide improved access to the new South Renton Transit Center, a key transportation hub. The proposed improvements include traffic signal retiming, modification, and synchronization; modifications to existing transit signal priority (TSP) installations; new and modified transit-only and Business Access Transit (BAT) lanes, bus queue jumps and other traffic channelization improvements. This proposed project will provide improved access to the new South Renton Transit Center and generate travel time benefits for the entire 17 mile RapidRide I Line corridor. Project outcomes include: 2 of 13 • Travel time savings between 5 and 19 minutes per trip on the corridor, with over 20% travel time savings in the PM peak; •Improved access to Regional Centers for transit riders, including historically transit dependent populations; • Improved access to approximately 138,000 jobs, with approximately 20,000 of those jobs located in regional growth centers; and • Increased transit ridership of between 4,000 and 6,000 new daily riders. -

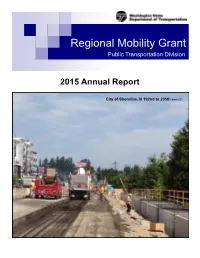

Regional Mobility Grant Program 2015 Report

Regional Mobility Grant Public Transportation Division 2015 Annual Report City of Shoreline, N 192nd to 205th GCA 6757 Regional Mobility Grant Program 2015 Annual Report Contact: Nicole Patrick, [email protected] or 360-705-6930 December 2015 Page Regional Mobility Grant City of Tukwila, Urban Transit Center GCA 6758 Intercity Transit, Hawks Prairie Park and Ride Contact: Washington State Department of Transportation Public Transportation Division Regional Mobility Grant Program Nicole Patrick, Grants Analyst 310 Maple Park Avenue PO BOX 47387 Olympia, WA 98504-7387 (360) 705-6930 [email protected] Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information Materials can be made available in an alternate format by emailing the WSDOT Diversity/ADA Compliance Team at [email protected] or by calling toll free, 855-362-4ADA (4232). Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may make a request by calling the Washington State Relay at 711. Title VI Notice to Public It is the Washington State Department of Transportation's (WSDOT) policy to assure that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex, as provided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise discriminated against under any of its federally funded programs and activities. Any person, who believes his /her Title VI protection has been violated, may file a complaint with WSDOT's Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). For Title VI complaint forms and advice, please contact OEO's Title VI Coordinator at (360) 705-7082 or (509) 324-6018. -

King County Metro Rapidride Performance Evaluation Report

King County Metro RapidRide Performance Evaluation Report Prepared for Prepared by December 2014 King County Metro RapidRide Performance Evaluation Report | 2 King County Metro CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................................................4 Performance Evaluation ................................................................................................5 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Performance Evaluation Summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 Comparison to other National BRT Service ..................................................................20 Performance Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 21 Cost Effectiveness of Capital Expenditures .................................................................22 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................................... 22 Cost Effectiveness Performance Summary .......................................................................................................... 22 Cost Effectiveness of Operating Costs ..........................................................................32 -

Joint Board Program Management Report 3Rd Quarter - 2014 |Page 1

July - September 2014 Joint Board Program Management Report 3rd Quarter - 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Report Purpose 1 Key Activities – Reporting Period 1 Customer Service Equipment & Facilities 3 Overview of Customer Activity & Contacts 4 System Operations Performance Data 6 a) System Operations ‐ Sales by Fare Product Type and Sales Channel/Location 6 b) System Operations – Retailer Report 12 c) System Operations ‐ Ridership Transactions/Boardings 13 d) System Operations – Cards in Circulation and in Use by Type 17 Promoting ORCA 18 Data Sources 21 Acronyms 21 Joint Board Program Management Report 3rd Quarter - 2014 |Page 1 Report Purpose The primary audience for this report is the seven agency ORCA Joint Board. The purpose of the report is to provide a high level quarterly overview of the performance of key customer facing system activities. The data presented may be useful to support business decisions such as the deployment of marketing or financial resources for system enhancements. The report may be modified at any time at the Joint Board’s request, as our operational experience grows, and/or we introduce system changes. 3rd Quarter Key Activities July The cumulative number of issued cards in circulation since April 2009 has reached over 2 million. King County Metro conducted a special account promotion– ‘In Motion July 28 – Nov 1’ aimed at residents along portions of RapidRide E and F lines. Eligible participants received an ORCA card with a two week Passport loaded with an attached customized card holder. ORCA cards loaded with a regional passport product were provided to 30‐40 participants attending the Leadership APTA Workshop that was held at the Mayflower Hotel in downtown Seattle July 22‐ 26. -

Historic and Archaeological Resources Technical Memorandum September 2020

Historic and Archaeological Resources Technical Memorandum September 2020 I-405 Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Consultant Quality Control Form Originator/ Approved Notes, as Version Title Date Drafted by Reviewed by by required 0 I-405 BRT December Environmental Larissa King Chris Initial Draft Historical and 20, 2019 Science Associates Rawlins Wellander Archaeological –Chris Lockwood (content) Resources Ph.D., Ed Reynolds Technical Chanda R. (tech edit) Memorandum – Schneider, B.A., Sandra Wise Draft Bryan Hoyt B.A., (QC) Alta Cunningham M.A., and Johanna Kahn M.Ar.H. 1 I-405 BRT February Environmental Larissa King Chris Revised Draft Historical and 18, 2020 Science Associates Rawlins and Wellander Archaeological –Chris Lockwood Lesley Mauer Resources Ph.D., (content) Technical Chanda R. Ed Reynolds Memorandum – Schneider, B.A., (tech edit) Second Draft Amber Grady M.A., Sandra Wise and (QC) Johanna Kahn M.Ar.H. 2 I-405 BRT March 30, Environmental Larissa King Chris Final version Historical and 2020 Science Associates Rawlins (Task Wellander Archaeological –Chris Lockwood Lead) Resources Ph.D., Ed Reynolds Technical Chanda R. (tech edit) Memorandum Schneider, B.A., Sandra Wise Amber Grady M.A., (QC) and Johanna Kahn M.Ar.H. 3 I-405 BRT May 15, Environmental Larissa King Chris Revised final Historical and 2020 Science Associates Rawlins (Task Wellander version Archaeological –Chris Lockwood Lead) Resources Ph.D., Ed Reynolds Technical Chanda R. (tech edit) Memorandum Schneider, B.A., Sandra Wise Amber Grady M.A., (QC) and Johanna Kahn M.Ar.H. Page i | AE 0054-17 | Historic and Archaeological Resources Technical Memorandum September 2020 I-405 Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Originator/ Approved Notes, as Version Title Date Drafted by Reviewed by by required 4 I-405 BRT June 12, Environmental Larissa King Chris Revised final Historical and 2020 Science Associates Rawlins (Task Wellander version Archaeological –Chris Lockwood Lead) Resources Ph.D., Ed Reynolds Technical Chanda R. -

Rapidride F Line Survey Results

RapidRide F Line Three Year Post- Implementation Survey Results Prepared for: King County Metro by Pacific Market Research King County Metro Contact Info 201 S. Jackson St Seattle, WA 98104 Phone: 206-553-3000 March 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 3 Background and Objectives .................................................................................. 3 Method ................................................................................................................... 4 KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................... 7 DETAILED FINDINGS .................................................................................... 12 Overall Satisfaction with Service ......................................................................... 12 Satisfaction with Service Elements for F Line and PreRapidRide ................... 12 Trip Time ........................................................................................................................... 13 Personal Safety .................................................................................................................. 14 Waiting Area/Bus Stop Where You Boarded for This Trip ....................................... 17 Things about Buses .......................................................................................................... 20 Ease of Transferring ........................................................................................................ -

Rapidride I Line Seattle, Washington Small Starts Project Development (Rating Assigned November 2020)

RapidRide I Line Seattle, Washington Small Starts Project Development (Rating Assigned November 2020) Summary Description Proposed Project: Bus Rapid Transit 17 Miles, 41 Stations Total Capital Cost ($YOE): $117.63 Million Section 5309 CIG Share ($YOE): $55.63 Million (47.3%) Annual Operating Cost (opening year 2023): $26.67 Million 6,300 Daily Linked Trips Current Year Ridership Forecast (2019): 2,139,500 Annual Linked Trips 8,500 Daily Linked Trips Horizon Year Ridership Forecast (2040): 2,863,500 Annual Linked Trips Overall Project Rating: Medium-High Project Justification Rating: Medium Local Financial Commitment Rating: High Project Description: King County Metro (Metro), proposes to implement bus rapid transit between the cities of Renton, Kent, and Auburn. The project includes 23 diesel electric hybrid buses, 1.95 miles of transit exclusive lanes, level boarding stations, off-board fare payment, and transit signal priority and queue jumps, and approximately 4,200 park and ride spaces. On weekdays, service is planned to operate every 10 minutes during daytime hours, and every 15 minutes during evening periods. On weekends, service is planned to operate every 15 to 30 minutes. Project Purpose: Southern King County has some of the highest proportions of low-income and minority populations in the county. The Project corridor is served today primarily by two of Metro’s most productive suburban bus routes; however, both bus routes experience delays and reliability problems due to roadway congestion. Metro is planning the BRT to provide more frequent, convenient, and higher quality transit service than exists today. The project provides connections to other high capacity transit services including Sounder Commuter Rail and other BRT routes in the area, Project Development History, Status and Next Steps: The project entered Small Starts Project Development in May 2019. -

Regional Mobility Grant Program, 2013-2015

Regional Mobility Grant Program Paula Hammond Secretary of Transportation Mark Eldridge Brian Lagerberg Regional Mobility Program Manager Public Transportation Director Overview • Moving Washington – The RMG program supports Moving Washington • Review – The 2013-2015 evaluation process and scoring criteria • Regional Mobility Grants – Continuing projects from 2011-2013 biennium • Applications – Proposals submitted for the 2013-2015 grant award cycle • Contacts – WSDOT Public Transportation Division 2 Regional Mobility and Moving Washington Providing a mechanism for the state to work with local governments to develop and implement solutions that benefit the entire transportation system Operating Roadways Managing Demand Adding Capacity Efficiently Strategically • Maximizes the efficient use of • Focuses on congested • Provides higher existing highway infrastructure state highway occupancy modes of by reducing vehicle trips and corridors transportation through vehicle miles traveled • Funds capital new or extended transit • Improves transit reliability, construction and new routes or increased reduce operating costs for or increased transit service frequency highway corridor users service projects 3 Regional Mobility Performance Measures and Results for Previous Projects Performance Measures An estimated annual reduction of 254 million miles in vehicle miles travelled An estimated reduction of 13.9 million annual in vehicle trips Four projects saving over 1.2 million hours annually in travel days An estimated 110.1 metric tons of CO2 reduced annually Project Results 19 park and ride lots constructed or expanded, with more than 6,225 parking stalls 12 new or expanded transit centers Seven high occupancy vehicle and business access transit lane projects Nine transit signal prioritization projects 55 equipment and bus purchases, operating or expanded transit service projects 1.2 miles of fixed guide way and railroad track 4 Regional Mobility Grants Continuing Projects $4,954,434 of the 2013-2015 funds will be allocated to continuing, 2011-2013 projects.