The Making of Fin De Copenhague & Mémoires;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18ª Bienal De São Paulo

CATÁLOGO GERAL 18~ BIENAL INTERNACIONAL DE SÃO PAULO 4 de Outubro a 15 de .... 0::;;"'-<:;;, de 1985 G GERAL Fundação Bienal de São Paulo Pavilhão Engenheiro Armando Arruda Pereira Parque Ibirapuera . São Paulo· Brasil Patrocínio Oficial Governo Federal Presidente José Sarney Ministério da Cultura Aluísio Pimenta, Ministro Ministério das Relações Exteriores Olavo Egydio Setubal, Ministro Governo do Estado de São Paulo Governador André Franco Montara Secretaria de Estado da Cultura Jorge da Cunha Lima, Secretário Prefeitura do Municipio de São Paulo Prefeito Mário Covas Secretaria Municipal da Cultura Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, Secretário • 2 • Fundação Bienal de São Paulo Presidente Perpétuo Diretoria Executiva Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho (1898/1977) Roberto Muylaert - Presidente Conselho de Honra Mário Pimenta Camargo 1- 10 Vice-Presidente Oscar P. Landmann - Presidente Pedro D'Alessio - 2.0 Vice-Presidente Luiz Femando Rodrigues Alves Henrique Pereira Gomes Luiz Diederichsen Villares João Augusto Pereira de Queiroz João Marino Stella Teixeira de Barros Conselho de Administração Thomaz Jorge Farkas José E. Mindlin - Presidente Comissão de Arte e Cultura Ermelino Matarazzo - Vice-Presidente Sábato Antonio Magaldi - Presidente Aldo Calvo João Marino - Representante da Benedito José Soares de Mello Pati Diretoria Executiva Ema Gordon Klabin Erich Humberg Casimiro Xavier de Mendonça Francisco Luiz de Almeida Salles Fábio Luiz Pereira de Magalhães Hasso Weiszflog Glauco Pinto de Moraes João Fernando de Almeida Prado Representante da Secretaria Municipal Justo Pinheiro da Fonseca de Cultura e .Associação Profissional Oscar P. Landmann de Artista Piásticos de S.P. Oswaldo Arthur Bratke Oswaldo Silva Luiz Diederichsen Villares Roberto Pinto de Souza Renina Katz Sábato Antonio Magaldi Representante da Associação Sebastião Almeida Prado Sampaio Profissional de Artistas Plásticos de S.P. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

The Game of War, MW-Spring 2008

The Game of War: Debord as Strategist By McKenzie Wark for Issue 29 Sloth Spring 2008 The only member of the Situationist International to remain at its dissolution in 1972 was Guy Debord (1931–1994). He is often held to be synonymous with the movement, but anti- Debordist accounts rightly stress the role of others, such as Asger Jorn (1914–1973) or Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005) who both left the movement as it headed out of its “aesthetic” phase towards its ostensibly more “political” one. Take, for example, Constant’s extraordinary New Babylon project, which he began while a member of the Situationist International and continued independently after separating from it. Constant imagined an entirely new landscape for the earth, one devoted entirely to play. But New Babylon is a landscape that began from the premise that the transition to this new landscape is a secondary problem. Play is one of the key categories of Situationist thought and practice, but would it really be possible to bring this new landscape for play into being entirely by means of play itself? This is the locus where the work of Constant and Debord might be brought back into some kind of relation to each other, despite their personal and organizational estrangement in 1960. Constant offered the kinds of landscape that the Situationists experiments might conceivably bring about. It was Debord who proposed an architecture for investigating the strategic potential escaping from the existing landscape of overdeveloped or spectacular society. Between the two possibilities lies the situation. Debord is best known as the author of The Society of the Spectacle (1967), but in many ways it is not quite a representative text. -

Annual Report 2017

STEDELIJK MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2017 AMSTERDAM CONTENTS Foreword 3 Message from the Supervisory Board 7 Chapter 1: Bold programming 10 Chapter 2: Caring for the collection 25 Chapter 3: More people visit the Stedelijk 32 Chapter 4: Education, symposia, publications 40 Chapter 5: A vital cultural institution in the city 53 Chapter 6: Sponsors, funds, and private patrons 57 Chapter 7: Organizational affairs 64 Chapter 8: Personnel 69 Chapter 9: Governance 73 Colophon Chapter 10: Financial details 78 Texts: Team Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam Editors: Vanessa van Baasbank, Marc Cincone, Frederike van Dorst, Financial Statements 2017 85 Udo Feitsma, Bart van der Heide, Daniëlle Lokin, Audrey Moestadja, Florentine Pahud de Mortanges, Marie-José Raven, Margriet Schavemaker, Irene Start, Ronald van Weegen, Geert Wissing Final editing: Irene Start, Sophie Tates Translation: Lisa Holden, Huan Hsu Design: Janna and Hilde Meeus Het jaarverslag en bijlagen zijn met de grootst mogelijke zorgvuldigheid vertaald naar het Engels. De Nederlandse versie is de versie waarover de accountant een goedkeu- rende verklaring heeft afgegeven. Mochten er (door de vertaling) toch verschillen zijn opgetreden tussen de Nederlandse en Engelse versie, dan is de Nederlandse versie leidend. The annual report and supplements have been translated into English with the greatest possible care. The auditor issued an unqualified opinion of the Dutch version. In the case of any discrepancies or variances (resulting from the translation) between the English translation and the Dutch annual report and the supplements, the Dutch Cover image: Gert Jan van Rooij Gert image: van Jan Cover version shall prevail. 2 FOREWORD On November 1, 2017, when I was appointed interim director, the museum was in the midst of a media storm, which began with newspaper reports and ended with the much-publicized depar- ture of Beatrix Ruf as director. -

Else Alfelt, Lotti Van Der Gaag, and Defining Cobra

WAS THE MATTER SETTLED? ELSE ALFELT, LOTTI VAN DER GAAG, AND DEFINING COBRA Kari Boroff A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Committee: Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor Mille Guldbeck Andrew Hershberger © 2020 Kari Boroff All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor The CoBrA art movement (1948-1951) stands prominently among the few European avant-garde groups formed in the aftermath of World War II. Emphasizing international collaboration, rejecting the past, and embracing spontaneity and intuition, CoBrA artists created artworks expressing fundamental human creativity. Although the group was dominated by men, a small number of women were associated with CoBrA, two of whom continue to be the subject of debate within CoBrA scholarship to this day: the Danish painter Else Alfelt (1910-1974) and the Dutch sculptor Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999), known as “Lotti.” In contributing to this debate, I address the work and CoBrA membership status of Alfelt and Lotti by comparing their artworks to CoBrA’s two main manifestoes, texts that together provide the clearest definition of the group’s overall ideas and theories. Alfelt, while recognized as a full CoBrA member, created structured, geometric paintings, influenced by German Expressionism and traditional Japanese art; I thus argue that her work does not fit the group’s formal aesthetic or philosophy. Conversely Lotti, who was never asked to join CoBrA, and was rejected from exhibiting with the group, produced sculptures with rough, intuitive, and childlike forms that clearly do fit CoBrA’s ideas as presented in its two manifestoes. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

Ed Van Der Elsken Archives 1

ED VAN DER ELSKEN ARCHIVES 1 NOBUYOSHI ARAKI LOVE ON THE LEFT EYE In collaboration with Taka Ishii Gallery 06.09. - 18.10.2014 For the opening exhibition of Ed van der Elsken Archives, we are pleased to present Love on the Left Eye featuring work from Nobuyoshi Araki’s (1940, Tokyo, JP) publication of the same title alongside works from Ed van der Elsken’s Love on the Left Bank. Almost identically titled to the photography book that brought Van der Elsken to prominence, Love on the Left Eye can be seen as an homage to the Dutch pho- tographer as well as a return to Araki’s early inspirations. Araki made the photographs that form Love on the Left Nobuyoshi Araki, Love on the Left Eye, 2014 Eye, with the vision from his right eye obscured due to a retinal artery obstruction. Shot on slide film, Araki used black magic marker to block out the right side of each image, before printing the photographs. The images thus show Araki’s vision, both as an artist and as an individual confronted by his mortality (having recently also recovered from pros- tate cancer). Araki came into contact with Love on the Left Bank in his twenties and took photo- graphs of women in poses inspired by the ones found in Van der Elsken’s book. At this late stage in his career and facing the prospect of loosing all sight from his right eye, we thus find Araki go- ing back to his early influences. “Death comes towards us all, you know,” he says. -

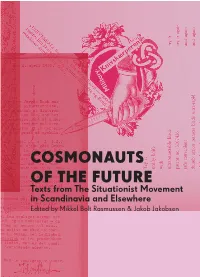

Cosmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist

COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen 1 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE 2 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere 3 COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA AND ELSEWHERE Edited by Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen COSMONAUTS OF THE FUTURE Published 2015 by Nebula in association with Autonomedia Nebula Autonomedia TEXTS FROM THE SITUATIONIST Læssøegade 3,4 PO Box 568, Williamsburgh Station DK-2200 Copenhagen Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 Denmark USA MOVEMENT IN SCANDINAVIA www.nebulabooks.dk www.autonomedia.org [email protected] [email protected] AND ELSEWHERE Tel/Fax: 718-963-2603 ISBN 978-87-993651-8-0 ISBN 978-1-57027-304-9 Edited by Editors: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen | Translators: Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Fabian Tompsett, Jakob Jakobsen | Copyeditor: Marina Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Vishmidt | Proofreading: Danny Hayward | Design: Åse Eg |Printed by: Naryana Press in 1,200 copies & Jakob Jakobsen Thanks to: Jacqueline de Jong, Lis Zwick, Ulla Borchenius, Fabian Tompsett, Howard Slater, Peter Shield, James Manley, Anja Büchele, Matthew Hyland, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, Stevphen Shukaitis, Jim Fleming, Mathias Kokholm, Lukas Haberkorn, Keith Towndrow, Åse Eg and Infopool (www.scansitu.antipool.org.uk) All texts by Jorn are © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg Asger Jorn: “Luck and Change”, “The Natural Order” and “Value and Economy”. Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Natural Order and Other Texts translated by Peter Shield (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 9-46, 121-146, 235-245, 248-263. -

Constant Nieuwenhuys-August 13, 2005

Constant Nieuwenhuys Published in Times London, August 13 2005 A militant founder of the Cobra group of avant-garde artists whose early nihilism mellowed into Utopian fantasy Soon after the war ended, the Cobra group burst upon European art with anarchic force. The movement’s venomous name was an acronym from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, the cities where its principal members lived. And by the time Cobra’s existence was formally announced in Paris in 1948, the young Dutch artist Constant had become one of its most militant protagonists. Constant did not hesitate to voice the most extreme beliefs. Haunted by the war and its bleak aftermath, he declared in a 1948 interview that “our culture has already died. The façades left standing could be blown away tomorrow by an atom bomb but, even failing that, still nothing can disguise the fact. We have lost everything that provided us with security and are left bereft of all belief. Save this: that we live and that it is part of the essence of life to manifest itself.” The Cobra artists soon demonstrated their own exuberant, heretical vitality. Inspired by the uninhibited power of so-called primitive art, as well as the images produced by children and the insane, they planned an idealistic future where Marxist ideas would form a vibrant union with the creation of a new folk art. Constant, born Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys, discovered his first motivation in a crucial 1946 meeting with the Danish artist Asger Jorn at the Galerie Pierre, Paris. They exchanged ideas and Constant became the driving force in establishing Cobra. -

Beyond the Black Box: the Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction

Beyond the Black Box: The Lettrist Cinema of Disjunction ANDREW V. UROSKIE I was not, in my youth, particularly affected by cine - ma’s “Europeans” . perhaps because I, early on, developed an aversion to Surrealism—finding it an altogether inadequate (highly symbolic) envision - ment of dreaming. What did rivet my attention (and must be particularly distinguished) was Jean- Isidore Isou’s Treatise : as a creative polemic it has no peer in the history of cinema. —Stan Brakhage 1 As Caroline Jones has demonstrated, midcentury aesthetics was dominated by a rhetoric of isolated and purified opticality. 2 But another aesthetics, one dramatically opposed to it, was in motion at the time. Operating at a subterranean level, it began, as early as 1951, to articulate a vision of intermedia assemblage. Rather than cohering into the synaesthetic unity of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk , works in this vein sought to juxtapose multiple registers of sensory experience—the spatial and the temporal, the textual and the imagistic—into pieces that were intentionally disjunc - tive and lacking in unity. Within them, we can already observe questions that would come to haunt the topos of avant-garde film and performance in the coming decades: questions regarding the nature and specificity of cinema, its place within artistic modernism and mass culture, the institutions through which it is presented, and the possible modes of its spectatorial engagement. Crucially associated with 1. “Inspirations,” in The Essential Brakhage , ed. Bruce McPherson (New York: McPherson & Co., 2001), pp. 208 –9. Mentioned briefly across his various writings, Isou’s Treatise was the subject of a 1993 letter from Brakhage to Frédérique Devaux on the occasion of her research for Traité de bave et d’eternite de Isidore Isou (Paris: Editions Yellow Now, 1994). -

The Situationist International on the 1960’S Radical Architecture: an Overview

ĠSTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ON THE 1960’S RADICAL ARCHITECTURE: AN OVERVIEW M.Sc. Thesis by Hülya ERTAġ Department : Architecture Programme : Architectural Design JANUARY 2011 ĠSTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL ON THE 1960’S RADICAL ARCHITECTURE: AN OVERVIEW M.Sc. Thesis by Hülya ERTAġ 502071027 Date of submission : 20 December 2010 Date of defence examination: 28 January 2011 Supervisor (Chairman) : Assis. Prof. Dr. Ġpek AKPINAR (ĠTÜ) Members of the Examining Committee : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Arda ĠNCEOĞLU (ĠTÜ) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bülent TANJU (YTÜ) JANUARY 2011 ĠSTANBUL TEKNĠK ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ FEN BĠLĠMLERĠ ENSTĠTÜSÜ DURUMCU ENTERNASYONEL VE 1960’LARDAKĠ RADĠKAL MĠMARLIK YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Hülya ERTAġ 502071027 Tezin Enstitüye Verildiği Tarih : 20 Aralık 2010 Tezin Savunulduğu Tarih : 28 Ocak 2011 Tez DanıĢmanı : Y. Doç. Dr. Ġpek AKPINAR (ĠTÜ) Diğer Jüri Üyeleri : Doç. Dr. Arda ĠNCEOĞLU (ĠTÜ) Doç. Dr. Bülent TANJU (YTÜ) OCAK 2011 FOREWORD I would like to express my deep appreciation and thanks to my advisor İpek Akpınar for all her support and inspiration. I thank all my friends, family and colleagues in XXI Magazine for their generous understanding. January 2011 Hülya ERTAŞ (Architect) v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................... ix LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... -

The Interventions of the Situationist International and Gordon Matta-Clark

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Potential of the City: The Interventions of The Situationist International and Gordon Matta-Clark A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Brian James Schumacher Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Chair Professor Teddy Cruz Professor Grant Kester Professor John Welchman Professor Marcel Henaff 2008 The Thesis of Brian James Schumacher is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii EPIGRAPH The situation is made to be lived by its constructors. Guy Debord Each building generates its own unique situation. Gordon Matta-Clark iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………… iii Epigraph…………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………... v Abstract………………………………………………………………….. vi Chapter 1: Conditions of the City……………………………………….. 1 Chapter 2: Tactics of Resistance………………………………………… 15 Conclusion………………………………………………………………. 31 Notes…………………………………………………………………….. 33 Bibliography…………………………………………………………….. 39 v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Potential of the City: The Interventions of The Situationist International and