Roald Amundsen and Capt Robert Falcon Scott's Expedition to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

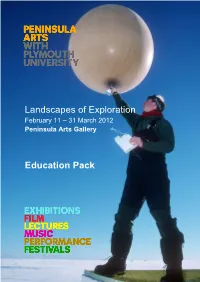

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

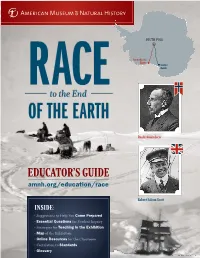

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

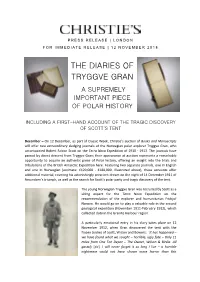

The Diaries of Tryggve Gran

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 12 NOVEMBER 2 0 1 8 THE DIAR IES OF TRYGGVE GRAN A SUPREMELY IMPORTANT PIECE OF POLAR HISTORY INCLUDING A FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT OF THE TRAGIC DISCOVERY OF SCOTT’S TENT December – On 12 December, as part of Classic Week, Christie’s auction of Books and Manuscripts will offer two extraordinary sledging journals of the Norwegian polar explorer Tryggve Gran, who accompanied Robert Falcon Scott on the Terra Nova Expedition of 1910 - 1913. The journals have passed by direct descent from Tryggve Gran; their appearance at auction represents a remarkable opportunity to acquire an authentic piece of Polar history, offering an insight into the trials and tribulations of the British Antarctic Expedition here. Featuring two separate journals, one in English and one in Norwegian (estimate: £120,000 - £180,000, illustrated above), these accounts offer additional material, covering his astonishingly prescient dream on the night of 14 December 1911 of Amundsen’s triumph, as well as the search for Scott’s polar party and tragic discovery of the tent. The young Norwegian Tryggve Gran was recruited by Scott as a skiing expert for the Terra Nova Expedition on the recommendation of the explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen. He would go on to play a valuable role in the second geological expedition (November 1911-February 1912), which collected data in the Granite Harbour region. A particularly emotional entry in his diary takes place on 12 November 1912, when Gran discovered the tent with the frozen bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers: ‘It has happened – we have found what we sought – horrible, ugly fate – Only 11 miles from One Ton Depot – The Owner, Wilson & Birdie. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN Voyage Handbook

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN voyage handbook MS ROALD AMUNDSEN VOYAGE HANDBOOK 20192020 1 Dear Adventurer 2 Dear adventurer, Europe 4 Congratulations on booking make your voyage even more an extraordinary cruise on enjoyable. Norway 6 board our extraordinary new vessel, MS Roald Amundsen. This handbook includes in- formation on your chosen Svalbard 8 The ship’s namesake, Norwe- destination, as well as other gian explorer Roald Amund- destinations this ship visits Greenland 12 sen’s success as an explorer is during the 2019-2020 sailing often explained by his thor- season. We hope you will nd The Northwest Passage 16 ough preparations before this information inspiring. departure. He once said “vic- Contents tory awaits him who has every- We promise you an amazing Alaska 18 thing in order.” Being true to adventure! Amund sen’s heritage of good South America 20 planning, we encourage you to Welcome aboard for the ad- read this handbook. venture of a lifetime! Antarctica 24 It will provide you with good Your Hurtigruten Team Protecting the Antarctic advice, historical context, Environment from Invasive 28 practical information, and in- Species spiring information that will Environmental Commitment 30 Important Information 32 Frequently Asked Questions 33 Practical Information 34 Before and After Your Voyage Life on Board 38 MS Roald Amundsen Pack Like an Explorer 44 Our Team on Board 46 Landing by Small Boats 48 Important Phone Numbers 49 Maritime Expressions 49 MS Roald Amundsen 50 Deck Plan 2 3 COVER FRONT PHOTO: © HURTIGRUTEN © GREGORY SMITH HURTIGRUTEN SMITH GREGORY © COVER BACK PHOTO: © ESPEN MILLS HURTIGRUTEN CLIMATE Europe lies mainly lands and new trading routes. -

Boreal Marine Fauna from the Barents Sea Disperse to Arctic Northeast Greenland

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/394346; this version posted December 16, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Boreal marine fauna from the Barents Sea disperse to Arctic Northeast Greenland Adam J. Andrews1,2*, Jørgen S. Christiansen2, Shripathi Bhat1, Arve Lynghammar1, Jon-Ivar Westgaard3, Christophe Pampoulie4, Kim Præbel1* 1The Norwegian College of Fishery Science, Faculty of Biosciences, Fisheries and Economics, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Norway 2Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, Faculty of Biosciences, Fisheries and Economics, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Norway 3Institute of Marine Research, Tromsø, Norway 4Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland *Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed, e-mail: [email protected], kim.præ[email protected] Keywords: Atlantic cod, Barents Sea, population genetics, dispersal routes. As a result of ocean warming, the species composition of the Arctic seas has begun to shift in a boreal direction. One ecosystem prone to fauna shifts is the Northeast Greenland shelf. The dispersal route taken by boreal fauna to this area is, however, not known. This knowledge is essential to predict to what extent boreal biota will colonise Arctic habitats. Using population genetics, we show that Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), beaked redfish (Sebastes mentella), and deep-sea shrimp (Pandalus borealis) specimens recently found on the Northeast Greenland shelf originate from the Barents Sea, and suggest that pelagic offspring were dispersed via advection across the Fram Strait. Our results indicate that boreal invasions of Arctic habitats can be driven by advection, and that the fauna of the Barents Sea can project into adjacent habitats with the potential to colonise putatively isolated Arctic ecosystems such as Northeast Greenland.