Testing for Racial Profiling in Traffic Stops from Behind a Veil of Darkness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Know the Color Wheel Primary Color

Introduction to Color/Hue Theory With Marlene Oaks Color affects us psychologically in nature, clothing, quilts, art and in decorating. The color choices we make create varying responses. Being able to use colors consciously and harmoniously can help us create spectacular results. Know the Color Wheel Primary color Primary color Primary color The color wheel is the basic tool for combining colors. The first circular color diagram was designed by Sir Isaac Newton in 1666. Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Colors Color theory in regards to light says that all colors are within white light—think prism, and black is devoid of color. In pigment theory, white is the absence of color & black contains all colors. We will be discussing pigment theory here. The primary colors are red, yellow and blue and most other colors can be made by various combinations of them along with the neutrals. The three secondary colors (green, orange and purple) are created by mixing two primary colors. Another six tertiary colors are created by mixing primary and secondary colors adjacent to each other. The above illustration shows the color circle with the primary, secondary and tertiary colors. 1 Warm and cool colors The color circle can be divided into warm and cool colors. Warm colors are energizing and appear to come forward. Cool colors give an impression of calm, and appear to recede. White, black and gray are considered to be neutral. Tints - adding white to a pure hue: Terms about Shades - adding black to a pure hue: hue also known as color Tones - adding gray to a pure hue: Test for color blindness NOTE: Color theory is vast. -

Original Or Non-Original Expressive Art Guide

Expressive Art Oregon 4-H Tip Sheet OriginalArts or Non-original Art Guide Does the work use design components created by someone else? (patterns, drawings, recognizable pictures or photos, stencils, stamps, pre-shaped forms) NO YES Original Art Division Non-original Art Division Member applies the elements and principles of design Member applies the elements and principles of to create work that is entirely their own design to create work that may incorporate pieces designed or created by others. Pre-designed component must not be the total design Drawing & Sketching (by technique) Drawing/Shading Techniques • Line Drawing Uses drawing, shading, texturing and/or three Uses any drawing medium that can make a distinct line dimensional shaping techniques with the aid of partial Examples include pencil, colored pencil, scratch art, pen and photographs, line drawings, tracing or stenciling that ink, felt tip markers the member did not create themselves Differences in lightness/darkness can be achieved by spacing Includes soft metal embossing, woodburning, scratch or thickness of distinct lines art, or drawing to complete or enhance a partial photo • Shaded Drawing of a subject Uses any drawing medium that can make varied differences in lightness and darkness without showing distinct lines Shading is not simply adding color, it is a technique that adds dimension or volume to the piece. It introduces degrees of darkness to render light and shadow. Examples include chalk, charcoal, pastels, pencil, and colored pencil • Line & Shaded Combination -

Darkness and Light: the Day of the Lordi

BIBLICAL PROPHECY—THINGS TO COME Darkness and light: The Day of the Lordi Now, brothers, about times and dates we do not need to write to you, for you know very well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. While people are saying, "Peace and safety," destruction will come on them suddenly, as labor pains on a pregnant woman, and they will not escape. But you, brothers, are not in darkness so that this day should surprise you like a thief. You are all sons of the light and sons of the day. We do not belong to the night or to the darkness. (1 Thessalonians 5:1-5) In these verses believers are called ―brothers.‖ Those who are saying, ―Peace and safety,‖ are unbelievers. God is reminding the Thessalonians that unbelievers will not escape judgment in the ―Day of the Lord.‖ However, believers are not in darkness, they are ―sons of the light,‖ sons of faith in Christ, and can look back on the accomplished salvation of Christ, which fulfilled Old Testament promises. They can look forward to the second coming of Christ, in the Day of the Lord, which consummates all of God’s prophecy/promises. The Day of the Lord was the high hope and the far-off goal of the Old Testament. It was, that toward which, the entire Old Testament program of God was moving. Everything in time and creation looked forward to and moved toward that day. The Old Testament era closed without it being realized, and up to today the Day of the Lord has not yet come. -

Color Wheel Value Scale

Name Date Period ART STUDENT LEARNING GUIDE: Color Wheel Value scale ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS . I know and understand the answers to the following questions: Pre-Project Post-Project Yes / N0 Yes / No What are the properties of the primary colors? How do you create secondary & tertiary/intermediary colors? How do you create tints & shades ? How do you locate the complementary colors? What are their properties? What is the difference between warm & cool colors? LEARNING TARGETS . 1. I can create a Color Wheel by mixing primary paint colors & adding black & white to create different Values (tints & shades). 2. I can construct a Color Wheel by using the following Element of Art: Color 3. I can construct a Color Wheel by using the following art techniques: Value (tints & shades) 4. I can analyze and evaluate the merit of my completed artwork by completing a student self-assessment. 5. I can thoughtfully plan and successfully create an artwork by staying engaged in class and being on-task at all times. KEY VOCABULARY . Color wheel – a tool used by artists to see how colors work together Primary colors – Red, Yellow, Blue (cannot be created by any other colors) Secondary colors – Orange, Violet/Purple, Green (created by combing two primary colors) Tertiary/Intermediary colors – created by combing a secondary color and a primary color (ex. Yellow-green) Warm colors – red, orange, yellow Cool colors – blue, green, purple Complementary colors – colors opposite of each other on the color wheel ( next to each other they appear brighter, mixed together they create brown) Tints – adding white to a color Shades- adding black to a color Value – the lightness or darkness of a color (tints and shades) Hue – pure color (no white or black added) Created by A. -

ATP Consumption by Mammalian Rod Photoreceptors in Darkness and in Light

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Current Biology 18, 1917–1921, December 23, 2008 ª2008 Elsevier Ltd All rights reserved DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.029 Report ATP Consumption by Mammalian Rod Photoreceptors in Darkness and in Light Haruhisa Okawa,1 Alapakkam P. Sampath,2 transduction. To calculate the energy required to pump out Simon B. Laughlin,3 and Gordon L. Fain4,* Na+ entering through the channels, which must be removed 1Neuroscience Graduate Program to keep the cell at steady state, we assumed a normal dark 2Department of Physiology and Biophysics resting current of 25 pA; mouse rod responses in excess of Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute 20 pA are routinely observed in our laboratories. Approxi- USC Keck School of Medicine mately 7% of the current is from Na+/Ca2+ exchange, so we Los Angeles, CA 90089 could directly estimate the Na+ influx in darkness (see Supple- USA mental Data available online). We then divided by 3 to calculate 3Department of Zoology ATP consumption by the Na+/K+ pump, because three Na+ University of Cambridge ions are pumped out of the rod for every ATP. The dependence Downing Street of ATP consumption on light intensity over the physiological Cambridge CB2 3EJ range was evaluated from measurements of mouse rod UK current responses to steady illumination [10] and are shown 4Departments of Physiological Science and Ophthalmology in Figure 1A. ATP utilization falls by an amount equivalent to University of California, Los Angeles 2.3 3 106 ATP s21 per pA decrease in inward current, from Los Angeles, CA 90095-7000 about 5.7 3 107 ATP in darkness to zero at an intensity of about USA 104 Rh* s21, which closes all the cGMP-gated channels. -

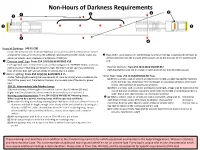

Non-Hours and Hours of Darkness Requirements

Non-Hours of Darkness Requirements Hours of Darkness: 340.01 (23) means the period of time from one-half hour after sunset to one-half hour before sunrise and all other times when there is not sufficient natural light to render clearly visible any Flags Under Load: Loads over 100 feet long must have red flags hung beneath the load at person or vehicle upon a highway at a distance of 500 feet. 20 foot intervals from the last axle of the power unit to the first axle of the lasted towed “Oversize Load” Sign: Trans 254.10 (4) (b) & MV2605 #18 unit. Each sign shall state, in black letters on a yellow background, "OVERSIZE LOAD," and may not be less than 7 feet long and 18 inches high. The letters of the sign may not be less Flag Size and Color: Trans 254.10 (3) (d) & MV2605 #17 than 10 inches high with a brush stroke of not less than 1.4 inches. Each flag shall be solid red or orange in color, and not less than 18 inches square. Amber Lighting: Trans 254.10 (2) (a) & MV2605 # 15 Corner Flags: Trans 254.10 (3) & MV2605 #17 Flags Amber flashing light meeting the requirements of Trans 254.10 (2) which is visible to the (a) When a vehicle, load, or vehicle and load is overlength, a single flag shall be fastened front of the power unit, from behind the load, and on each side of the load or power at the extreme rear of the load if the overlength or projecting portion is 2 feet wide unit. -

From Darkness to Sun and Stars

From Darkness to Sun and Stars Lesson 1: From darkness God created light, sun, moon and stars. God created light on the first day of creation. On the fourth day he filled the day with the sun and the night with moon and starts. Infants and toddlers can relate to going to sleep at night and waking in the day. Scripture: Genesis 1:3-5, 14-19 “…God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.”…God made two great lights—the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars.” Teaching Items to Collect Class Schedule (Some are in the Theme Boxes) (45 minutes) Peep tubes (tins that children Welcome Time (15 minutes) look into to view what is On the mat in the soft corner. Time to settle inside): in and free play. Music or singing. o Light o Sun Bible Time and Lesson (20 minutes total) o Moon and Stars At the table Glittery silver star on a stick. Bible Time Lesson: Talk about the fact that God Star stickers made sun, moon and stars. Various toy dolls, animals and Experiment with light and dark with blankets (You will pretend to torches/flashlights. put them to sleep while it is Sing “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” or night-dark and wake them “This Little Light of Mine”. Pretend when it is morning-light.) putting babies and animals down to Torches/Flashlights sleep and then waking them up. Craft: (optional) Black & light blue Fairy lights paper for day/night. -

170. Use of Infrared Radiation in the Study of Fish Behavior

USE OF INFRARED RADIATION IN THE STUDY OF FISH BEHAVIOR MarineLIBRARYBiological Laboratory MAY 8- iy56 WOODS HOLE, MASS. SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT- FISHERIES No. 170 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE EXPLANATORY NOTE The series embodies results of investigations, usually of restricted scope, intended to aid or direct management or utilization practices and as guides for administrative or legislative action, it is issued in limited quantities for official use of Federal, State or cooperating agencies and in processed form for economy and to avoid delay in publication United States Department of the Interior, Douglas McKay, Secretary Fish and Wildlife Service, John L. Farley, Director USE OF INFRARED RADIATION IN THE STUDY OF FISH BEHAVIOR by Rea E . Duncan Fishery Research Biologist Special Scientific Report- -Fisheries No. 170. Washington, D. C. March 1956 ABSTRACT Infrared radiation can be used to observe the actions of fish in the dark. Experi- ments demonstrated that the behavior of fingerling silver salmon (O^. kisutch ) was not affected by infrared radiation. The infrared filters used did not pass wavelengths visible to an observer, and the actions of the fish were observed through an infrared viewer. The fish were not attracted or repelled by steady radiation, and they did not exhibit a fright reaction to flashing radiation. The orientation pattern in still or flowing water was not affected; there was no indication that the fish could perceive the wavelengths employed. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 Problem 1 Water Penetration 1 The Eye and the Spectrum 3 Infrared Radiation and Animals Other Than Fishes 3 MATERIALS 4 EXPERIMENTS ON THE REACTION OF FISH TO INFRARED RADIATION .. -

Molecular Basis of Dark Adaptation in Rod Photoreceptors

1 Molecular basis of dark c.s. LEIBROCK , T. REUTER, T.D. LAMB adaptation in rod photoreceptors Abstract visual threshold (logarithmically) against time, following 'bleaching' exposures of different Following exposure of the eye to an intense strengths. After an almost total bleach light that 'bleaches' a significant fraction of (uppermost trace) the visual threshold recovers the rhodopsin, one's visual threshold is along the classical bi-phasic curve: the initial initially greatly elevated, and takes tens of rapid recovery is due to cones, and the second minutes to recover to normal. The elevation of slower component occurs when the rod visual threshold arises from events occurring threshold drops below the cone threshold. within the rod photoreceptors, and the (Note that in this old work, the term 'photon' underlying molecular basis of these events was used for the unit now defined as the and of the rod's recovery is now becoming troland; x trolands is the illuminance at the clearer. Results obtained by exposing isolated retina when a light of 1 cd/m2 enters a pupil toad rods to hydroxylamine solution indicate with cross-sectional area x mm2.) that, following small bleaches, the primary intermediate causing elevation of visual threshold is metarhodopsin II, in its Questions and observations phosphorylated and arrestin-bound form. This The basic question in dark adaptation, which product activates transduction with an efficacy has not been answered convincingly in the six about 100 times greater than that of opsin. decades since the results of Fig. 1 were obtained, Key words Bleaching, Dark adaptation, is: Why is one not able to see very well during Metarhodopsin, Noise, Photoreceptors, the period following a bleaching exposure? Or, Sensitivity more explicitly: What is the molecular basis for the slow recovery of visual performance during dark adaptation? In considering the answers to these questions, there are three long-standing observations that need to be borne in mind. -

Project 2 Darkness & Solar Light

Project 2 Darkness & Solar Light Suggested age: 3 to 5 Little Sun Education Project 2 Darkness & Solar Light Summary Outcomes This project explores darkness and solar light, Through investigation, students learn to it addresses the experience of darkness and understand the effects of darkness on their what happens when it is night and when it is senses and how it affects their movement. day. Where does the sun go at night and how Through conversation, they learn what can we use sunlight at night and how can we happens when the sun is not around, why use sunlight when it is dark? we experience darkness, and why access to light at night is important. Suggested age range: 3 to 5 years Preparation: Subjects Covered: Science, Environment, • Read through the program once Art, Geography • Prepare required materials Materials: Little Suns, paper, colored markers • Allocate a dark room for use during or crayons, a dark room. the lesson Time required: Preparation: 5 minutes • Ensure the Little Suns are charged and Teaching: 40 minutes can be used Little Sun | Education 2 Little Sun Education FEEL How darkness feels … Begin the class in a dark room. Ask the students to form a circle and lay on the ground. Ask: It’s dark, what can you see? Can you see colors? Can you hear sounds? Ask the students to move their arm or their leg, to wriggle in the dark. Ask: Ask: How does it feel? When is it normally dark? At night? Ask the students when they have experienced How do we see at night? darkness before. -

HUE, VALUE, SATURATION All Color Starts with Light

HUE, VALUE, SATURATION What is color? Color is the visual byproduct of the spectrum of light as it is either transmitted through a transparent medium, or as it is absorbed and reflected off a surface. Color is the light wavelengths that the human eye receives and processes from a reflected source. Color consists of three main integral parts: hue value saturation (also called “chroma”) HUE - - - more specifically described by the dominant wavelength and is the first item we refer to (i.e. “yellow”) when adding in the three components of a color. Hue is also a term which describes a dimension of color we readily experience when we look at color, or its purest form; it essentially refers to a color having full saturation, as follows: When discussing “pigment primaries” (CMY), no white, black, or gray is added when 100% pure. (Full desaturation is equivalent to a muddy dark grey. True black is not usually possible in the CMY combination.) When discussing spectral “light primaries” (RGB), a pure hue equivalent to full saturation is determined by the ratio of the dominant wavelength to other wavelengths in the color. VALUE - - - refers to the lightness or darkness of a color. It indicates the quantity of light reflected. When referring to pigments, dark values with black added are called “shades” of the given hue name. Light values with white pigment added are called “tints” of the hue name. SATURATION - - - (INTENSITY OR CHROMA) defines the brilliance and intensity of a color. When a pigment hue is “toned,” both white and black (grey) are added to the color to reduce the color’s saturation. -

Name: Edhelper the Electromagnetic Spectrum

Name: edHelper The Electromagnetic Spectrum Look around you. What do you see? You might say "people, desks, and papers." What you really see is light bouncing off people, desks, and papers. You can only see objects if they reflect light (or produce it). Think about it- if the room were in total darkness, would you still be able to see the people, desks, and papers? No. We see light as brightness or the opposite of darkness. Light is a type of energy made by the vibration of electrically charged particles. What we call light is just part of this energy. Scientists call light electromagnetic radiation. Some sources of light are the sun, other stars, and fire. We can feel heat from the sun and fire. We can't feel the heat from stars because they are too far away, but they do make heat just as our sun, also a star, does. Light transfers energy in the forms of light and heat. Light transfers energy in other forms that are harder to detect. The sun produces a huge amount of energy. The energy the sun produces travels in little particles called photons. There are different kinds of energy produced by the sun. Some light we can see, just a tiny part of it, called visible light. Other types of light energy are invisible. There are different wavelengths of light, or really, we should call it electromagnetic radiation or EM for short. Other types of EM are very long radio waves and very short wavelengths like x-rays and gamma rays.